Weekly #64: No Investment Is Risk-Free... And That’s the Point (And a Quick Survey)

Portfolio +4.9% YTD, 2.3x the market since inception. Plus the case for taking calculated leaps of faith and a short survey to make Beating the Tide easier to navigate and more valuable.

Hello fellow Sharks,

This week the portfolio continued widening its outperformance versus the S&P 500. If you want to skip straight to the numbers, jump to the Portfolio Update.

In this Weekly I want to ask you a huge favor. I’m sending a survey because I want to make this newsletter as useful and easy to navigate as possible for all of you. I’ve heard from a few of you already, and I want to make sure everyone’s voice is heard.

When I started, the site had only one type of article and a screenshot of my portfolio. Over time, it grew organically. I now publish weeklies, deep dives, trade alerts, company updates and educational pieces. I linked directly to my portfolio (paid & free) so you can see updates in real time.

Many of you asked for more transparency, so I added a watchlist with target prices and risk/reward metrics, and I built a tracker for all stock picks (paid & free) since the newsletter launched. Each addition has made the site more powerful, but also more complex. At this point, the site does more, but it also feels harder to navigate than it should.

I need your feedback to see what works, what doesn’t, and what I should simplify. Your responses will help me streamline the navigation and focus on what delivers the most value to you.

I want everyone to participate. More responses means better decisions. As a thank‑you, I’ll randomly pick 10 responses for a free month of premium. If you already pay, I’ll add one free month to your subscription. The survey will stay open until Saturday, January 17, 2026. I’ll send a reminder on Thursday. If you want to enter the draw, add your email at the end (optional).

Remember, I’m an analyst, not a web designer. Your candid feedback is truly valuable in shaping a site that helps you on your investment journey.

Enjoy the read, and have a great Sunday!

~George

Table of Contents:

In Case You Missed It

Why I closed the JD.com position

This week I walked through my decision to exit JD.com [JD 0.00%↑].

The short version: the risk-reward deteriorated. Competitive pressure intensified, and margins didn’t improve. So the path to durable value creation became more uncertain. When the thesis weakens and opportunity cost rises, I move on. I laid out what went wrong and what I misjudged.

New position added to the portfolio

I also sent out a trade alert announcing a new position in the portfolio.

The full deep dive is coming in the next couple of weeks, where I’ll break down the business, the upside case, and the key risks in detail.

Thought of the Week: No Investment Is Without a Leap of Faith

I want to start with a story about one of my most memorable investments: Daqo New Energy [DQ 0.00%↑]. A few years ago, I spent months poring over DQ’s financials and industry dynamics, determined to understand every angle of the investment. By 2017, it had become the lowest-cost polysilicon producer in the world, taking that title from GCL-Poly.

DQ achieved that by benefiting from ultra-cheap electricity in Xinjiang, low raw material costs, inexpensive equipment, and continuous process improvements. Electricity is a huge part of polysilicon production cost, and Xinjiang’s coal-rich grid gave DQ a big edge. It was almost ironic: coal power was enabling cheaper solar panel materials, talk about using the old world to fuel the new!

I built a detailed financial model forecasting the cash flows, margins, and growth. The valuation looked incredible. DQ was trading at just 4x EV/EBITDA and 5x earnings, despite having some of the highest profit margins in the industry. It was shockingly cheap by any standard. I felt like I’d struck gold, but I also knew I had to earn that upside by understanding the risks.

As you should have noticed by now, every deep dive I write has a dedicated “Risks” section and that is because there is no reward without risk in stock investment.

In the case of DQ, first, competition was a real concern. Its cost advantage might not last forever as rival were setting up shop in Xinjiang too. Cheap coal power isn’t a secret, and new entrants could copy DQ’s playbook. I estimated Daqo had maybe a 3–4 year head start before local competitors caught up, but after that, the moat could narrow.

There was also the risk of government policy: what if Xinjiang’s authorities hiked electricity prices? That would hit Daqo’s cost advantage right in the gut. In my Seeking Alpha article at the time, I explicitly warned that an upward revision in Xinjiang’s power tariffs would hurt Daqo’s operations.

Then came technological risks. Solar technology is not static, and I worried about the obsolescence of the very product DQ makes: polysilicon. One potential disruptor was the advent of fluidized bed reactor (FBR) technology, which some believed could produce polysilicon more cheaply than the traditional process Daqo uses. At the time, only one company (REC Silicon) had partially succeeded in scaling FBR, but if it ever worked broadly, Daqo’s cost advantage could evaporate.

The second tech risk was a shift in solar panel manufacturing: the industry’s move from older slurry-based wafer slicing to diamond-wire sawing. This new slicing tech dramatically reduces silicon waste, meaning panel makers need less polysilicon per wafer.

On top of these company-specific risks, I also weighed macro and industry factors. Solar farm economics depend on interest rates (farms are often ~70% funded by debt), so rising rates could hurt solar project returns and slow down demand. Even the price of oil can matter as a plunge in oil could make conventional energy cheaper and dampen urgency for renewables. None of these are under Daqo’s control, but I had to consider them.

So there I was: a model projecting a multibagger, a list of very real risks, and that tingling feeling you get when you think you’ve found a winner but know you might be missing something. I double- and triple-checked my work.

I had a decision to make: do I invest or not?

In the end, I took the leap.

The risk/reward skew was simply too attractive to pass up. DQ’s upside potential outweighed the risks I saw. I accepted that no amount of analysis could eliminate the uncertainties completely. Instead, I made sure I understood them and sized my investment so that even in a downside case, it wouldn’t be catastrophic.

I’m glad I did.

The investment worked out even better than I’d hoped. Over the following years Daqo’s stock surged, validating a lot of my thesis. From the $5 price at which I first recommended it, DQ rose to a peak of $130 (but I exited at $95 as the risk:reward was starting to tilt at that price), vastly outperforming the market.

The risk paid off. But it easily could have gone the other way, that’s something we can’t forget. And that brings me to this week’s broader thought: every investment requires doing your homework… but at some point, you have to take a leap of faith, because there’s no such thing as a riskless investment.

No Such Thing as a Riskless Investment

Every investment, no matter how compelling, carries risk. There is no perfect, sure-thing, risk-free equity. It doesn’t exist. If it did, everyone would pile into it until the price went up and the return went down!

We live in a world of uncertainty, and investing is the art of making decisions under that uncertainty. As Peter L. Bernstein put it in Against the Gods, the defining idea of modern times is the mastery of risk, the notion that the future isn’t just left to fate, and that we can attempt to understand and manage risk. We can’t eliminate risk (short of hiding money under a mattress, which carries its own risks…), but we can try to quantify and control it.

Let’s take an example. Earlier this year, I wrote about TSMC.

It’s arguably one of the best-run companies in the world, a linchpin of the tech industry. The upside in TSMC is clear (I won’t repeat it here, just read the deep dive). But the risk section of that piece was sober reading. The biggest risk? Geopolitics. Specifically, the possibility of China invading Taiwan. It’s a low-probability risk, but definitely not zero. And if it happens, the outcome for investors would be catastrophic.

How do you even hedge something like that?

The uncomfortable answer is: you really can’t. You either stay out of Taiwan assets entirely or you stay invested and hope for the best. Think about that for a second: “hope for the best” is not exactly a comforting risk mitigation strategy. That’s the reality for something that big and unhedgeable.

Does that mean nobody should own TSMC or other Taiwanese stocks? Some might indeed choose to avoid them purely because of that tail risk. That’s a valid choice for those who can’t stomach it. But others (such as myself) will decide that the reward of owning a stake in one of the most critical companies on the planet is worth the risk, as long as they size their positions appropriately. If we froze every time we encountered a scary risk, we’d never invest in anything. Every worthwhile investment has a risk attached. If it didn’t, the payoff would be snatched away by the market in an arbitrage of greed and fear.

In fact, the only investments generally considered “risk-free” are government bonds of stable, trustworthy governments. And even those are only relatively risk-free (they won’t default, perhaps, but inflation can still bite).

In practice, when we say “risk-free rate,” we usually mean something like short-term U.S. Treasury bills. But a 3-month T-bill or a 10-year government bond is not going to double your money.

Far from it.

Right now, for example, 3-month U.S. Treasuries yield 3.6%.

That’s fine for parking cash, but it won’t build wealth quickly. Any investment that aims for higher returns will by necessity carry higher risk. This concept is called the risk premium and is the extra return an investor demands (or is promised) for taking on additional risk.

If a risky asset offered the same return as a safe government bond, why would anyone bother with the risky asset? You wouldn’t as a rational investor would just buy the government bond. Higher return must come with higher risk; otherwise everyone would pile into the higher return asset until its expected return fell. This is foundational to how markets function.

Now, that doesn’t mean all risks are created equal or that taking any crazy gamble is rewarded. The art is to figure out which risks are worth taking. Which risks are mispriced or manageable such that we are paid handsomely for bearing them.

For example, I was willing to take on DQ’s various risks because I assessed that those risks were less likely to materialize, or their impact was manageable, whereas the market was underestimating DQ’s earnings power if things went right.

In other cases, I might look at a stock and see tons of risk but very little upside, those I pass on. The key is that I focus on risk-adjusted return. Investing is not just about making money; it’s about avoiding losing money. Risk control is fundamental. Risk is not truly quantifiable as a single number, and it’s certainly not the same as volatility. Real risk is the risk of permanent loss of capital. A stock that swings 5% a day isn’t “risky” in the sense I care about, it’s the prospect of it never coming back that matters.

That’s why, paradoxically, stocks can be most risky when they seem safest (after they’ve shot up and everyone loves them), and conversely sometimes a hated, beaten-down stock can be less risky because all the bad news is priced in. Be especially wary when someone claims an investment is “risk-free.” Often, that label simply means people have underestimated or forgotten the risks.

In the late 90s, for example, people thought Cisco [CSCO 0.00%↑] and Microsoft [MSFT 0.00%↑] were “no-brainer” stocks until the dot-com crash reminded everyone that no stock is a sure thing. Understanding risk means acknowledging what could go wrong, even when things look great, and recognizing how much is unknowable.

Weighing the Risk vs. Reward

So how do we actually use this understanding in practice?

For me, it comes down to always examining both sides of the equation: the potential upside and the potential downside. It sounds obvious, but many (sometimes I fall victim to this as well) get seduced by a good story or a shiny forecast and forget the latter half.

As the saying goes, “Take care of the downside, and the upside will take care of itself.” In my watchlist and investment process, I force myself to explicitly write down not just my target price for a stock (what I think it’s worth under a base or bullish scenario), but also a worst-case price or downside scenario.

In fact, I even compute a rough risk/reward ratio for each idea: essentially, upside potential versus downside risk. For example, if I think a stock trading at $100 could be worth $150 in a year (+50%), but in a bad-case it might fall to $80 (–20%), then the risk/reward is +50%/–20%. That’s a 2.5-to-1 positive skew. I like the odds when I see that.

On the other hand, if a stock has, say, +20% upside but –50% downside (perhaps it’s a richly valued growth stock that could drop hard if it disappoints), the risk/reward is poor, even if the story sounds exciting. By keeping an eye on this risk/reward metric, I discipline myself to think in two directions. It’s a simple practice, but it has saved me from chasing a lot of overhyped situations. It also reminds me that no investment is worth it if the downside is literally unbounded.

I grew up around instability, so I obsess over downside first. I believe that in life we should focus on avoiding loss first, even above maximizing gains. Because if you can limit your downside, the upside tends to take care of itself through the power of compounding.

When I was looking at Daqo, for instance, the stock was so cheap relative to its assets and earnings power that a lot of bad news was already baked into the price. That valuation cushion was my margin of safety. It gave me confidence that even if polysilicon prices dipped or other hiccups occurred, Daqo was unlikely to be a disastrous investment because at that price it was valued at barely book value and 5 times earnings. Indeed, DQ’s price-to-book ratio at the time was around 0.8x, far below peers like Wacker or other solar companies that traded at 1.5–2x book. This undervaluation was a buffer.

Of course, a low valuation alone doesn’t protect you from all risk. Plenty of “cheap” stocks become value traps. I have fallen into some of them over the years such as Taylor Brands (read my thesis here) and ANFI (here).

But in DQ’s case, the low multiples reflected, I believed, an over-discounting of the risks. The market was essentially saying: “This company is small, in a cyclical industry, and located in China. It deserves a very low valuation.” My analysis agreed with the reasons for caution but showed that the company’s quality more than compensated for those risks.

In other words, the market was paying me (in the form of a low entry price) to take those risks, and I was willing to accept that bargain. Was I getting adequately compensated for the uncertainties here? That was the crucial question.

Embrace Risk, Just Do It Wisely

The phrase “leap of faith” might sound a bit scary or non-analytical, but I think it captures a fundamental truth: after you’ve done all the research, crunched all the numbers, and weighed all the scenarios, you eventually reach a point where you must make a decision without knowing the outcome.

That’s the leap.

You will never have perfect information or absolute certainty, not in life nor in investing. This is where investing transcends pure spreadsheet analysis and becomes as much about psychology and discipline. You have to be comfortable with the risks you’re taking. If you’ve done your homework, those risks should be calculated. You understand them, you’ve tried to minimize them, maybe you’ve mitigated some (through diversification, position sizing, hedging where possible), and you genuinely believe the odds are in your favor. But you also acknowledge that there are no guarantees. You prepare, and then you trust your judgment.

As I mentioned last week, I went fishing and I see how this even applies in that scenario. Before we went fishing, we checked the weather, inspected the boat, went at the optimal time that fish should be feeding, got the right bait… but once you set sail, there’s always a chance of a sudden storm or that fish are not feeding or that someone caught all the fish before you. But if you’re not willing to ever face a storm or accept that you might return home without any fish, you’ll never leave the harbor. And a boat isn’t made to stay in harbor indefinitely.

That means understanding the difference between prudent risk and foolish risk (you don’t go fishing when there is a tsunami warning). It means being humble about what you don’t know (hence building in margins of safety). It means being honest with yourself about your own risk tolerance; if a scenario like a Taiwan invasion or a 50% market crash would keep you up at night and force you to sell at the worst time, factor that in and size accordingly (or avoid if need be).

It also means learning from mistakes. If a risk does materialize and you lose money, the key question is: Was my analysis wrong, or was I right but just unlucky this time? If you were wrong, adjust your process so you don’t overlook that risk again. If you were right but unlucky, remind yourself that even good decisions can have bad outcomes in the short run. That’s just probability at work.

I’ll leave you with this. Howard Marks said, “You can’t predict. You can prepare.” We prepare by doing our homework, researching companies deeply, understanding their business, mapping out scenarios. We prepare by studying history, reading books to absorb the wisdom of those who navigated risks before us. We prepare by constructing our portfolios with care, balancing offense and defense.

But at the end of the day, we have to act. We have to put capital at risk to get a return. And that means accepting uncertainty. Every stock purchase, every investment, is made in the fog of an uncertain future. Embrace that fact. Rather than seeking mythical “risk-free” bets, focus on getting compensated for the risk. Demand that margin of safety. Double-check that your potential reward justifies the leap. And then, if it does… take the damn leap of faith. After all, if there’s no leap to take, there’s probably no reward on the other side.

Portfolio Update

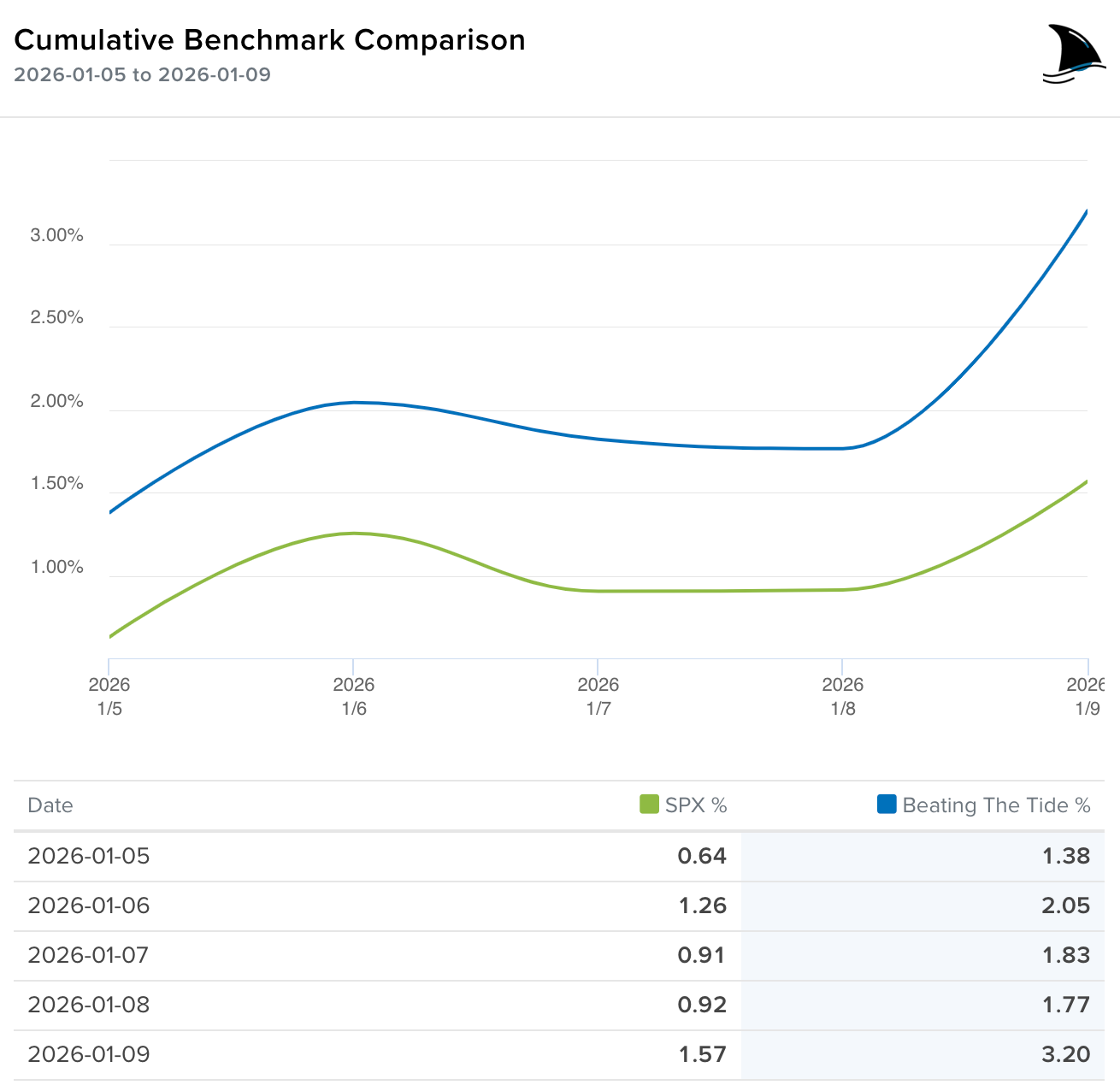

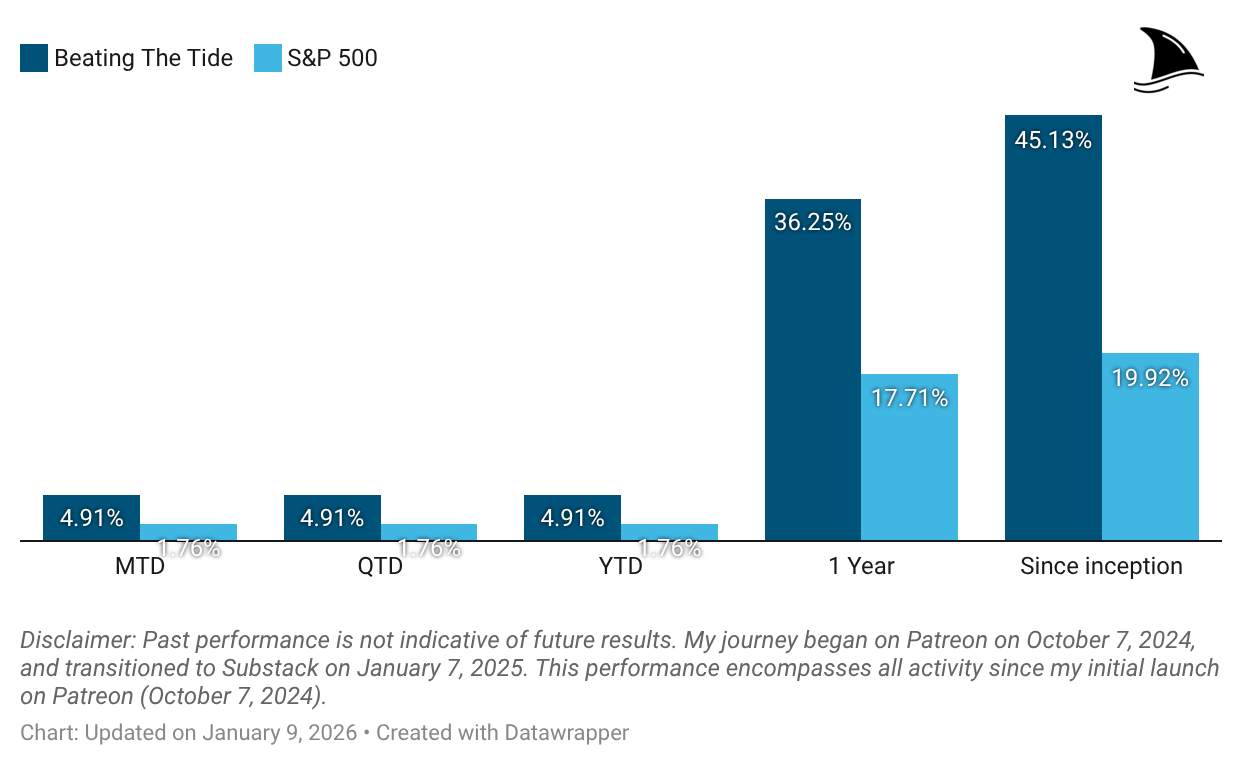

The portfolio ended the week higher than the S&P 500 expanding my outperformance.

Month-to-date: +4.9% vs. the S&P 500’s +1.8%.

Since inception: +45.1% vs. the S&P 500’s +19.9%. That’s 2.3x the market.

Portfolio Return

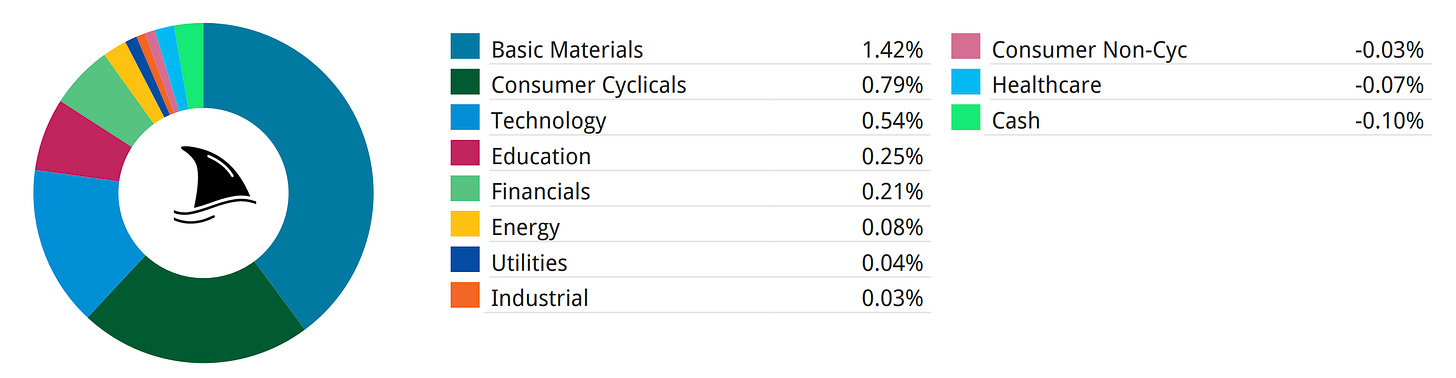

Contribution by Sector

Gold, consumer cyclicals and tech led the positive performance.

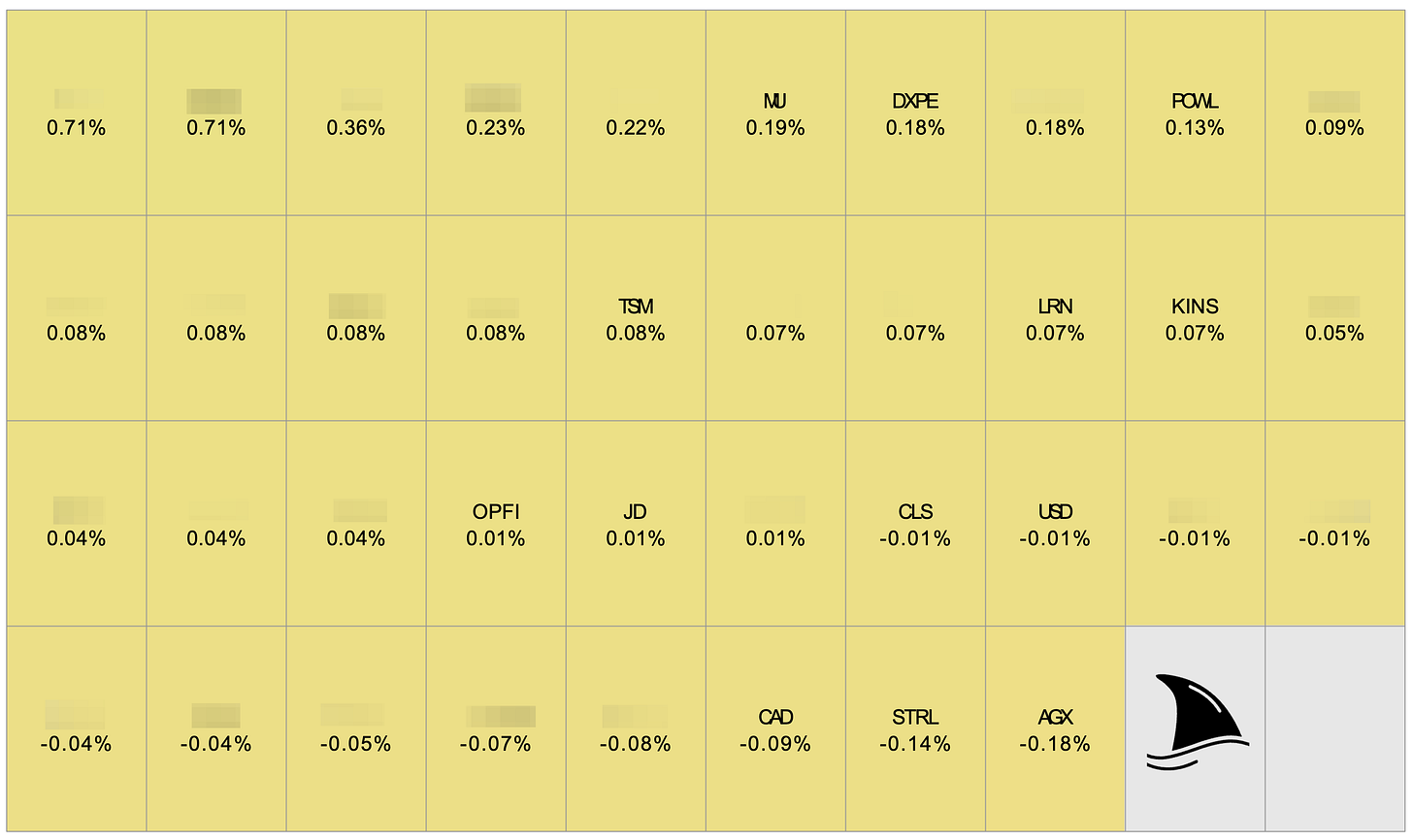

Contribution by Position

(For the full breakdown, see Weekly Stock Performance Tracker)

+18 bps DXPE 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

+13 bps POWL 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

+8 bps TSM 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

+7 bps LRN 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

+7 bps KINS 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

+1 bps OPFI 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

-1 bps CLS 0.00%↑ (TSX: CLS) (Thesis)

-14 bps STRL 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

-18 bps AGX 0.00%↑ (Thesis)

That’s it for this week.

Stay calm. Stay focused. And remember to stay sharp, fellow Sharks!

Further Sunday reading to help your investment process: