Weekly #43: Perfect Earnings Streak & Why Incentives Rule Everything

A flawless 7/7 earnings beat streak, portfolio +16.8% YTD (2.1x the S&P 500), and a Thought of the Week on why agents often win at your expense...unless you align the incentives.

Hello fellow Sharks,

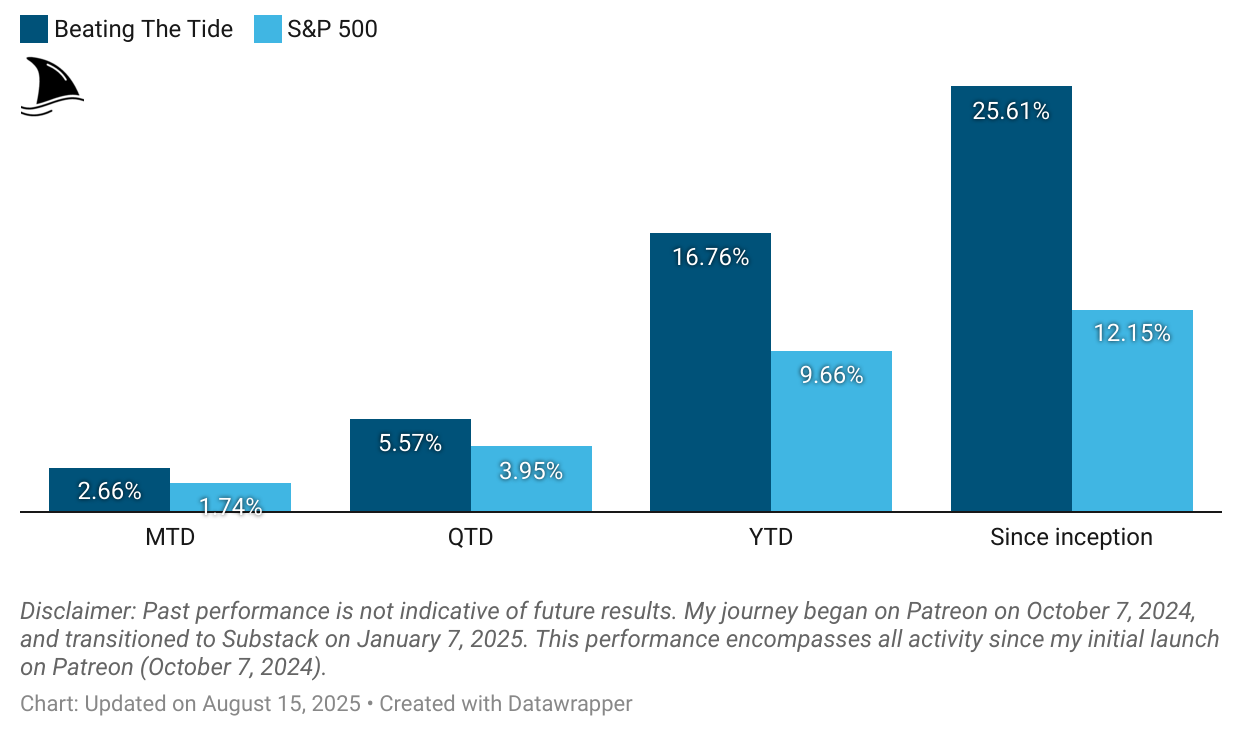

The portfolio kept moving higher this week (now +2.7% MTD, +16.8% YTD, and 2.1x the market since inception). If you want to skip straight to the numbers, jump to the Portfolio Update.

This week, we went a perfect 7-for-7 on earnings beats as every company reporting delivered above expectations on both revenue and EPS.

This week’s Thought of the Week looks at a simple but powerful lens for understanding both markets and life: the principal–agent problem. From Renaissance mercenaries to Wall Street research desks to construction crews outside my Toronto corner, the incentives at play explain more than most headlines ever will.

Enjoy the read!

~George

Table of Contents:

In Case You Missed It

Why I Took Profits and the One Risk I Couldn’t Ignore

GM 0.00%↑

I recently closed my GM position on August 6 after locking in a +18.7% gain. The original bull case leaned on GM’s bold EV ramp-up, slashing costs, and sheer dominance in the U.S. market, all while trading at a laughably low valuation.

A lot of that thesis played out beautifully: EV deliveries surged, margins held up amid tariff pressure, and U.S. operations remained rock solid. But as the year unfolded, new risks crept in: tougher Chinese EV competition, rising warranty and tariff costs, and a slump in free cash flow made the outlook murkier than when I went in. So I shifted strategy, exited GM, and funnelled that capital into a higher-conviction idea that’s already up +25% in just days. Read more.

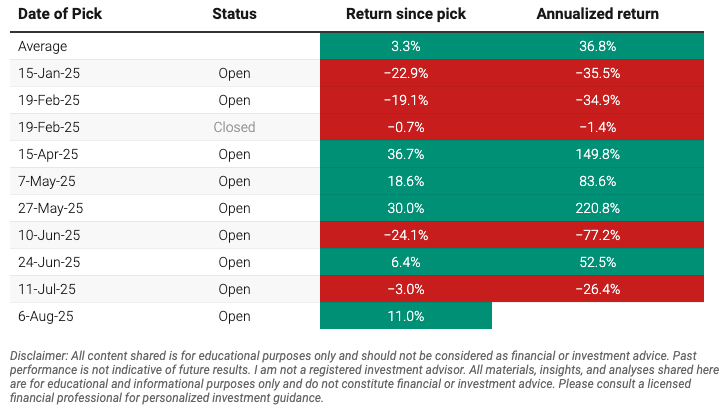

Stock Picks Tracker

A lot of you have asked how the stock picks have been performing since launching this newsletter. So I built a tracker that lays it all out, updated in real time. Free subscribers can see the big-picture results, and paid subscribers get the full breakdown with every single pick and detail.

You can access them via the links below or via the homepage (right side).

Stock Picks Performance (full detail)

And remember: it’s not just about the individual stock picks I’ve put out along the way. On day one of this newsletter, I also laid out a starter portfolio of high-conviction names. If you’re new here, don’t just chase the picks I’ve added since; make sure you look at the portfolio too. That’s where a lot of the compounding is happening.

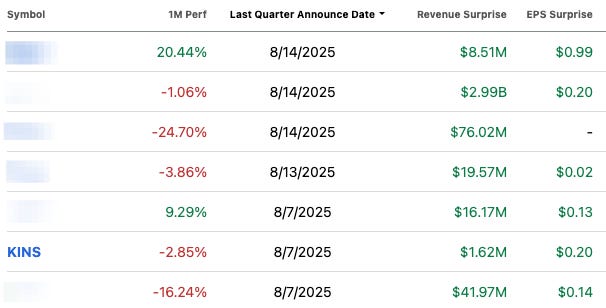

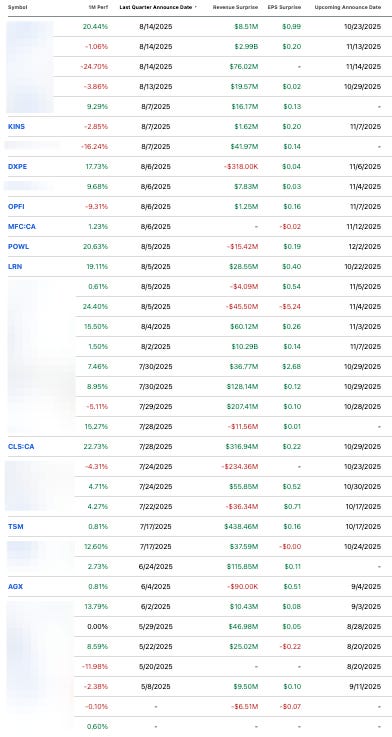

Earnings Round Up: 7-for-7 on Beats

Since the last update, seven more companies in the portfolio have reported earnings. Every single one beat both revenue and EPS estimates. A pretty flawless run. On Wednesday, I’ll share a detailed breakdown of the report from KINS, so keep an eye out for that if you want the full story.

Out of the 36 companies in the portfolio, 33 have reported, of which only four missed EPS estimates and nine missed revenue estimates.

Thought of the Week: Principals, Agents — and Why the Repairs at My Corner Got Done on Time

Not sure where you live, but here in Toronto, we all have the scars from how big infrastructure somehow takes forever to build. If you’ve been here a while, you know exactly what I mean. I left for Chile in 2011 with the Eglinton LRT freshly announced and everyone buzzing about a shiny new line that would make crosstown commutes humane again.

I visited in 2013…still under construction.

Visited again in 2017…still under construction.

Moved back for good in 2020…still under construction.

Fast forward to 2025 and, yep, we’re still… not riding it.

Yes, there are many excuses, things like “utilities weren’t where the drawings said they were,” “unexpected soil and groundwater conditions,” “design changes,” “contractor disputes,” “delays in vehicle procurement and software integration,” “COVID shutdowns,” “safety certification and testing,” “scope creep,” “neighbourhood mitigation,” and “cost-overrun approvals.”

Some of those are probably real, some are half-true, and some are pure cover.

But my working theory is simpler: the incentives haven’t been aligned. When principals and agents want different things—when success for one side doesn’t equal success for the other—everything turns to molasses.

Then there’s the Yonge and Queen closure in May 2023 for the Ontario Line. The plan said: 4.5 years, ending in 2027/8. My gut says… longer. Not because I’m a cynic by profession (although investing does put you through that boot camp), but because I’ve learned to start any timeline by asking a boring question most people skip: Who’s the principal here, who’s the agent, and what exactly are they being paid to optimize?

This dovetails with what happened right outside my place. In May 2025, my intersection (King & Church) was closed to restore the streetcar tracks and replace 142-year-old watermains. The city said it would be completed by the end of August.

The first weeks? Not promising. Slow start. The vibe felt… leisurely. I’d look out and see more elbows on tables than hands on tools. Workers spent more time at St. Louis Bar & Grill across the street having beers and debating how many kilos are in a litre of water (true story) than actually laying anything. I’m not one to police lunch breaks, but I’m also not blind.

And then something changed. I don’t know what triggered it, a new foreman, a memo from someone’s boss, a “we don’t want to be working in a blizzard” epiphany, a carrot, a stick, both. Whatever it was, the tempo snapped. Crews were suddenly going later. There was weekend work. People were still out there after 7 p.m. (maybe not strictly legal for noise, but I wasn’t complaining and apparently neither were my neighbours).

Yesterday (August 15), they wrapped the last big bits.

They even painted the signs today!

And now it’s just testing: on track to reopen August 31, as promised.

What happened?

I know overtime is paid at 2x (I used to work at the TTC back in my engineering days) and that can create an incentive to stretch things out. But there are other incentives too. Working in a Toronto winter is its special punishment. Or maybe there was a bonus for hitting the August 31 milestone.

Who knows. What I do know is this: for a brief moment, the incentives actually lined up. Everyone pointed in the same direction—get it done—and, surprise, things got done.

That’s the whole point of this Thought of the Week: principal versus agent. If you understand that one idea, you can explain half of what frustrates you about investing… and frankly, life.

A Quick Tangent (and Why “The News” Isn’t Neutral)

Before we go all-in on principals and agents, let me clear up something about bias because it connects. People follow the news religiously expecting neutral truth beamed from Mount Objectivity. If you believe that, please stop. Everything is biased. I’m biased. You’re biased. This post is biased. Sometimes it’s intentional, often it isn’t. It’s just how brains work.

Two people can look at the same “fact” and walk away with two entirely different conclusions because each brain filters through its own wiring, millions of connections sculpted by experience. Every sentence you read creates new connections on top of old ones. So yes, bias happens before you even realize it. (If I tried to blame most of our marital spats on those mental filters, my wife wouldn’t buy it. But hey, it was worth a shot, right? 😉)

Now, bias matters because it’s tied to incentives. The people delivering your news are not in the “help you achieve financial independence” business; they’re in the “keep you watching and clicking” business. That’s their incentive. Which makes them an agent of their advertisers, of their own ratings, of engagement metrics and not your agent. Keep that thought; we’ll come back to Jim Cramer’s bells and whistles later.

Principals and Agents

A principal is the person who ultimately owns the outcome and bears the risk. The agent is the person you hire to help you get that outcome. Easy, right? You are the principal of your savings. When you pay someone to do something with your money or on your behalf, they become your agent.

The issue is simple to describe and hard to fix: principals and agents rarely want exactly the same thing. They might say they do. The PowerPoint will say they do. The contract might kind-of sort-of try to make it so. But incentives leak. Agents face their own pressures, targets, and pay structures that push them to make choices that are perfectly rational for them and suboptimal for you.

Two textbook problems show up a lot:

Moral Hazard: After an agreement, the agent takes actions you can’t fully observe or control. Those actions affect your outcome, not theirs. Think: a contractor cutting corners behind drywall; you won’t see it until after you’ve paid.

Adverse Selection: Before an agreement, the agent has private information you don’t, and the side with more info is the one that gets to choose. Think: a broker pushing a product because it pays a higher commission; you can’t easily see that incentive or the true quality gap.

Add information asymmetry (they know more than you), plus measurement problems (you pay for what you can measure, even if it’s not what you truly want), plus good old human nature (we respond to what we’re rewarded for), and you’ve got the soup most of modern life is cooked in.

An everyday example: You want to renovate your kitchen. You’re the principal. The designer, the project manager, the plumber and the contractor become your agents. Your dream is a beautiful, durable kitchen at a fair price, in the shortest time, that doesn’t compromise quality. Your contractor’s dream is to meet the contract specs in the fastest, cheapest way that still gets them paid, with minimal callbacks and maximum margin. Those aren’t identical dreams. The misalignment isn’t evil; it’s just math. (And again, most contractors are good people who take pride in their work.)

The Toronto Case Study, as Lived From My Corner

Infrastructure is a masterclass in principal–agent misalignment. The principal is the public (and, operationally, the city/province). Agents include: contractors, subcontractors, utilities, engineers, inspectors, consultants, community-relations teams, technology vendors, lawyers, and on and on. Each has its own budget, its own timeline risk, its own legal exposure, its own KPI. When the job is to “finish Eglinton,” but the daily rewards are tied to “avoid penalties,” “don’t eat unexpected costs,” “minimize legal risk,” “don’t be the one who signs off on something that later fails,” and “hit this quarter’s utilization targets,” guess what wins?

If you’ve ever watched a project manager try to coordinate five companies across a single intersection (streets, rails, watermains, telecom, power) you’ve seen the issue up close. The mayor can want the line open by May; your councillor can hold a press conference; you can fume at the detour signs, but the crews actually trenching are optimizing something that looks nothing like your mental model of “go faster.” And that’s before politics jumps in (election cycles, budgets, accountability theatre).

This is why I try to resist the temptation to rant about individual workers or a specific crew. The person leaning on a shovel is an easy target, but outliers aside, most crews work inside the constraints they’re given. If your pay is based on time-and-materials, your risk is getting yelled at for mistakes, your tools show up late because someone else’s budget was cut, and your constraints are “don’t break anything underground because the liability is four times your revenue,” you will move slowly. If your pay is tied to milestones with a real carrot for early completion, with proper coordination and decision authority across all the tangled org charts, suddenly, the same people move fast.

Same bodies, different incentives.

When Agents Go Rogue: A Short Tour From Renaissance Italy to Wall Street

History won’t stop teaching the same lesson: when agents get paid to optimize something other than the principal’s outcome, weird things happen.

Start in Renaissance Italy. City-states like Florence, Venice, and Milan (the principals) hired condottieri, mercenary captains and their companies (the agents), to fight their wars. Pay was set by condotte (contracts) that rewarded time served, troop counts, and campaign duration. Bonuses sometimes sweetened the pot for specific objectives; penalties existed for obvious betrayal. On paper, it all sounded rational.

In practice, many condottieri figured out that avoiding decisive battles was good business. Real fights meant real casualties, which shrank tomorrow’s billable army and raised the risk of a dead (or captured) manager, terrible for repeat revenue. So campaigns became elaborate manoeuvres, sieges, symbolic clashes, and negotiated surrenders. The era produced great paintings and comparatively few body counts.

Machiavelli, never short on opinions, blasted mercenaries for being brave in friendly company and timid when it mattered.

Translation: paid for time, not outcomes.

The principals wanted security and decisive results; the agents wanted extended retainers and reusable troops.

Same tune, different century.

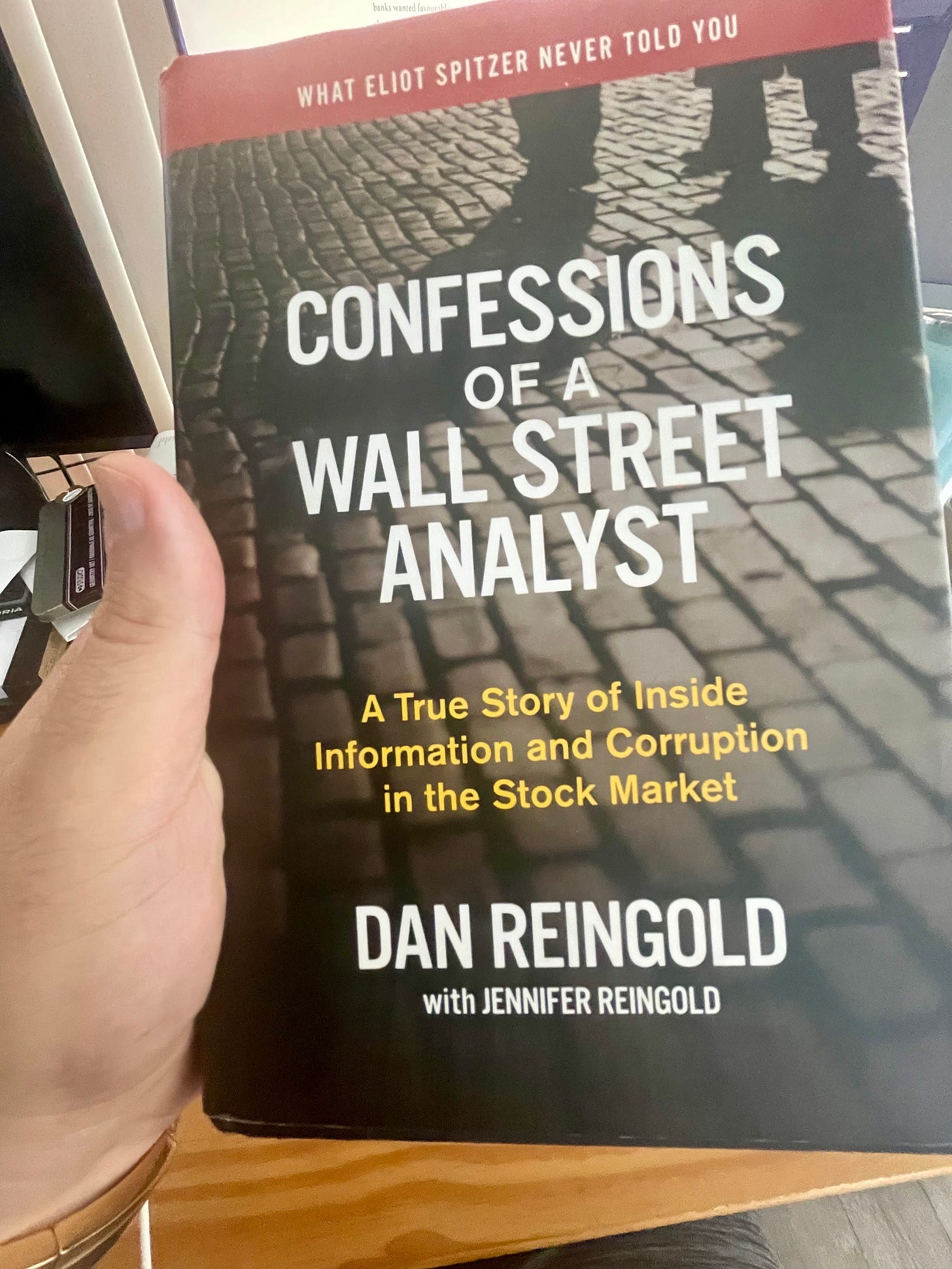

Fast-forward to the late-1990s dot-com bubble. Investors (principals) leaned on star sell-side research analysts (agents) for “objective” ratings at banks like Merrill Lynch, Salomon Smith Barney, and Morgan Stanley. What many didn’t appreciate was the conflict at the core: analysts worked inside firms collecting investment-banking fees from the same companies that those analysts covered. Favourable research greased lucrative underwriting and advisory relationships. Unsurprisingly, the public “Strong Buy” sometimes lived awkwardly beside private emails calling the same stocks “junk.”

Analysts polishing a rating to curry favour for a personal ask; emails instructing researchers, “If you can’t say something positive, don’t say anything”; and “banking reasons” quietly overruling attempted downgrades. When the bubble burst, retail investors ate the losses, trust cratered, and regulators led by New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer extracted a $1.4B global settlement.

Dan Reingold’s Confessions of a Wall Street Analyst is still a great read.

Banks were forced to wall off research from banking and provide independent research alongside their own. Did that fully fix misaligned incentives? No. In 2025, the conflicts haven’t vanished; they’re just subtler.

Now zoom to the mortgage machine, 2002–2008. At the top sat end investors like pensions and insurers (principals) seeking safe income. Between them and the homeowner was a long chain of agents from brokers, lenders, investment banks, to rating agencies, paid on volume and deal flow. The faster you pushed product, the more you earned.

Penalties for being wrong? Mostly none.

Predictably, loans that shouldn’t have been made were made; risks that shouldn’t have been glossed over were glossed over; securities that shouldn’t have been rated “AAA” were stamped “AAA.” When the music stopped, the principals got the bill. Not a grand conspiracy just incentives doing exactly what they were wired to do.

Add Enron for completeness. Shareholders and employees (principals) relied on executives and the board (agents) to steward the business. Management’s pay was tied heavily to stock price and reported earnings, so management engineered the numbers. Losses and debt were stuffed off-balance-sheet, performance was flattered with accounting tricks, and a passive board failed to rein it in. Executives cashed out along the way; when reality arrived, the company imploded, and principals were left with the ruins.

Again: pay for the wrong thing, and you’ll get the wrong thing…at scale.

The fix is never perfect, but it’s always the same directionally: shorten the distance between action and accountability; pay for outcomes, not activity; and put authority and responsibility in the same place. When principals do that, agents behave very differently on battlefields, in boardrooms, and on trading floors.

Investing Is Principal vs. Agent, in 4K

The same idea applies directly to investing. You are the principal of your savings. Brokers, financial advisors, tax advisors, gurus, news outlets, and investing newsletters (such as this one) are agents. Your goal as principal, to grow your capital at the highest risk-adjusted rate you can live with, may not be the same as your agents’ goals.

A broker might want you to trade often to collect commissions or to route your orders in ways that benefit their P&L. They don’t wake up thinking, “How can I help this person stick to a 20-year plan through a drawdown?” They wake up thinking, “How do we hit today’s targets and compliance checklists?”

A financial advisor might be paid a percentage of assets under management. That can be fine, but notice the subtle pushes: if their revenue falls when you pay down your mortgage or fund your kid’s tuition, their incentive is to nudge you to keep assets invested (sometimes even when de-risking would be right for you). If they’re commission-based on specific products, there’s a pull toward the ones that pay them more. “Fee-only fiduciary” is the gold standard because the incentive is cleaner. But even then, you want to understand their workflows and what they track.

A fund manager might be benchmarked quarterly and compensated with a bonus tied to short-term numbers. Guess how that shapes risk-taking around quarter-end window-dressing. In private markets, “2 and 20” fees can turn average outcomes into solid paydays for the agent even if the principal’s returns are mediocre. Asset gathering often beats alpha.

Gurus and courses often make more money selling dreams than compounding capital. Their incentive is to make you feel like you’re one secret away from easy riches…so you buy the next secret.

News outlets optimize for engagement and emotions, not your long-term net worth. Fear and outrage hold eyeballs. “This one weird trick the Fed doesn’t want you to know about” is a headline for a reason.

Even investing newsletters have business models. Some chase subscriber counts and pageviews at any cost because that’s the metric they’re paid on. Clickbait today, churn tomorrow. Sometimes the whole strategy is to outrage-bait retail, then sell ads to brokers who profit when retail gets whipsawed. Neat little loop, if you’re into that kind of thing.

So what to do in such a situation?

#1: Understand the divergent goals

Ask: How is this person paid? What do they track? What would count as a “win” for them even if it’s a “loss” for me? What are they blind to because their dashboard doesn’t show it?

#2: Try to align goals or put controls in place

Build contracts, processes, and habits that make doing the right thing the easiest thing.

#3: Simplify the chain of agents

The fewer layers between you and the outcome, the fewer places incentives can bend things. More layers = more leakage.

#4: Pre-commit to rules that protect your future self

Sometimes the most dangerous agent is present-you working against future-you. Automatic contributions, written checklists, and “cooling-off” periods beat adrenaline every time.

#5: Measure what you actually care about, not just what’s easy to count

Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure. If you measure clicks, you’ll get clicks; if you measure long-term performance, you might actually get performance.

How I Try to Align This Newsletter With You

I practice what I preach. I’ve tried to align this newsletter as much as possible with subscribers. For example, I invest all my liquid assets into my own recommendations (with one carve-out: an account I use to sell secured puts, as I’ve mentioned here).

We live or die on the same ideas. We share the same incentive: get the best stock picks in the portfolio and then sit on our hands when that’s the right move.

And because I don’t depend on this newsletter for income, it’s more hobby than a hustle, I don’t chase growth at all costs. I don’t buy subs. I don’t flood your inbox with thirteen micro-posts a day to juice engagement. I avoid clickbait titles even when they’d almost certainly “perform.”

Less noise, more signal.

If that slows growth, good. My goal is compounding, not dopamine.

The Best Disguised Agent of All: The News

I want to focus on the news because it’s the most disguised agent that people don’t recognize. Shows like Jim Cramer’s are entertainment. Full stop.

If you think the mission is to give you the quiet, boring, patient habits that lead to financial freedom… I hate to break it to you, but that would be a terrible business model for them. If you reach your goals, automate your savings, hold your positions, and stop chasing shiny objects, you watch less TV. You click fewer links. You refresh fewer tickers. Which means—poof—someone’s KPI goes red.

That’s why Jim has bells and buzzers. That’s why Bloomberg cycles guests to talk tariffs, geopolitics, “emergency” charts, and the CEO who just said the thing that moves the stock for forty-eight hours.

It’s a show, and a good one.

But ask yourself a hard question:

Not “How many did I feel smart about for twenty minutes?” How many actually made you meaningful money relative to the hours spent staring at a chyron? If you’re honest, you’ve probably lost more than you’ve gained trading what TV told you to trade.

None of this is an indictment of individual anchors or reporters. Just incentives. The format is optimized to keep you in your seat. It’s not optimized to make you wealthy. If anything, those goals are often at war.

Reduce the noise, because most of what you hear as “news” is an agent trying to get your attention, not a mentor trying to make you money.

The Boring Toolkit for Aligning Agents (and Protecting Yourself)

If you’re still with me, here’s a simple playbook. It works.

With Advisors

Ask “How do you get paid if I do X versus Y?” Then shut up and listen. If the answer is foggy, that’s your answer.

Prefer fee-only fiduciaries over commission-based sellers. If you do pay AUM fees, set expectations: “Please tell me when spending down or de-risking is better for me, even if it lowers your fee.”

Align time horizons. If you’re a decade-plus investor, don’t hire someone who reports like a day trader.

With Brokers

Minimize friction. If the platform makes you itch to trade, you’re paying the entertainment tax.

Know what happens to your orders. If payment for order flow, internalization, or other routing policies are part of the business model, understand the trade-offs and choose eyes-open.

With Funds and Managers

Distrust asset gatherers. A manager with $200B under management and a glossy ad campaign is optimizing scale, not idiosyncratic alpha.

Watch for “career-risk” behaviours. A manager hugging the index but charging active fees is not your agent; they’re the benchmark’s.

With Contractors (Literal or Metaphorical)

Structure the contract around outcomes where possible. Milestone payments, holdbacks for defects, and clarity on what “done” means.

Don’t forget carrots. If you want the project done by August 31, an early-completion bonus at least gives your agent permission to re-optimize.

With News and Content

Put friction between you and the feed. I’m not saying don’t consume news; I’m saying consume it on your schedule, not theirs.

Choose long-form over hot takes. If something really matters, it’ll matter tomorrow.

With Yourself (the Sneakiest Agent)

Automate what you can. Set the default to “do the right thing.” Automatic transfers beat motivation.

Use checklists. Reduce variance in your process so adrenaline doesn’t get to be your portfolio manager.

Write down your thesis and the kill-switch conditions before you buy. Future-you will thank you when present-you wants to panic at 10:17 a.m.

The Meta-Agency Problem: Your Present Self vs. Your Future Self

Here’s a twist I find useful in my own process: there’s a principal–agent battle playing out inside you. Present-you is an agent. Future-you is the principal. Present-you wants to feel safe in a drawdown and brilliant in a melt-up. Present-you wants to check the portfolio every twenty minutes and “do something” because doing nothing feels like failure. Future-you wants discipline, compounding, and time in the market.

This is why I’m a broken record about pre-commitment. Rules that bind present-you to future-you’s interests are the single most effective alignment trick I know. Examples: a rule to wait 24 hours before acting on anything you saw on TV. A rule to reread your original thesis before touching a position. A rule to size positions by risk, not conviction. A rule to record why you sold, not just why you bought.

Boring? Extremely.

Effective? Also extremely.

“Isn’t This a Bit Cynical?”

At first glance, talking about incentives like this can sound cynical, as if I don’t trust anyone.

I actually find it the opposite.

Understanding incentives helps me avoid blaming individuals for outcomes produced by systems. It lets me be generous about people and unsentimental about structures. It also keeps me from getting surprised by the obvious. If I pay for something I don’t want, I shouldn’t be shocked when I get more of it.

And sometimes you do meet people and teams who live above their incentives:

There are contractors who refuse to cut corners when no one is watching.

There are advisors who tell clients to pay off debt even when it shrinks AUM.

There are reporters who leave clicks on the table to tell a nuanced story.

Those people exist. When you find them, cherish them. Just don’t build your entire plan on hoping everyone else will be like them.

Again, think back to Buffett’s owner-operator model. He looks for managers whose incentives are naturally aligned with owners, people who treat a company’s capital like their own, preferably because a lot of it is their own. He avoids compensation schemes that reward short-term games. He buys businesses where the culture runs itself because the incentives are simple and baked in. When people quote his line about “looking for managers who are owners,” that’s agency design in a sentence.

A Checklist You Can Actually Use

Who is the principal here? (Who bears the ultimate risk?)

Who are the agents? (All of them: first-, second-, and third-order.)

How does each agent get paid? (Cash, options, prestige, job security, hours, renewals.)

What do they measure? (And what’s not measured that you actually care about?)

Where can they hide? (Ambiguity, handoffs, layers.)

What is the cheapest way for them to “win” even if you lose? (The game they’ll inevitably play.)

What contract, metric, or habit would turn their cheapest route into your desired outcome?

What can you simplify? (Fewer agents, fewer handoffs.)

What can you pre-commit to? (Rules that bind present-you to future-you.)

And the most important: What will you stop paying for? (Activity, drama, attention.)

One Last Word on Toronto (Because I’m Not Done Being Surprised)

I’m still kind of shocked that my corner is reopening on schedule. I went from watching beer-math at St. Louis Bar & Grill (“Is a litre of water a kilo?”) to listening to grinders at 8 p.m. while someone yelled measurements through a mask. I don’t know what memo went out. I don’t know who approved which bonus or who threatened what penalty. I just know that when the incentives finally got tuned, the same people with the same tools, in the same city with the same weather, got the same work done… fast.

And that’s the lesson I’ll keep hammering in investing and in life: systems drift toward whatever the incentive landscape points to. The great trick is to recognize when you’re accidentally paying for the wrong thing and to change the terrain.

Be the principal. Identify the agents. Ask blunt questions about pay. Structure outcomes, not activity. And then (this might be the hardest part) ignore the carnival barkers telling you to look over there, right now, because something shocking just happened and you must react in the next 90 seconds.

You don’t have to. You can let them perform. You can let them shout. And you can quietly do the very un-televised work of compounding.

Portfolio Update

The portfolio moved higher this week.

Month-to-date: +2.7% vs. the S&P 500’s +1.7%.

Quarter-to-date: +5.6% vs. the S&P 500’s +3.9%.

Year-to-date: +16.8% vs. the S&P’s +9.7%, a gap of 710 basis points.

Since inception: +25.6% vs. the S&P 500’s +12.1%. That’s 2.1x the market.

Portfolio Return

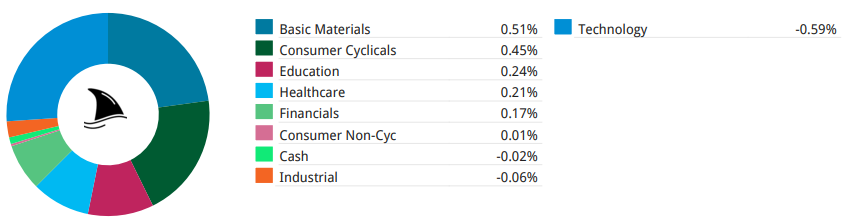

Contribution by Sector

Gold, consumer cyclicals and education led the gains, partially offset by tech.

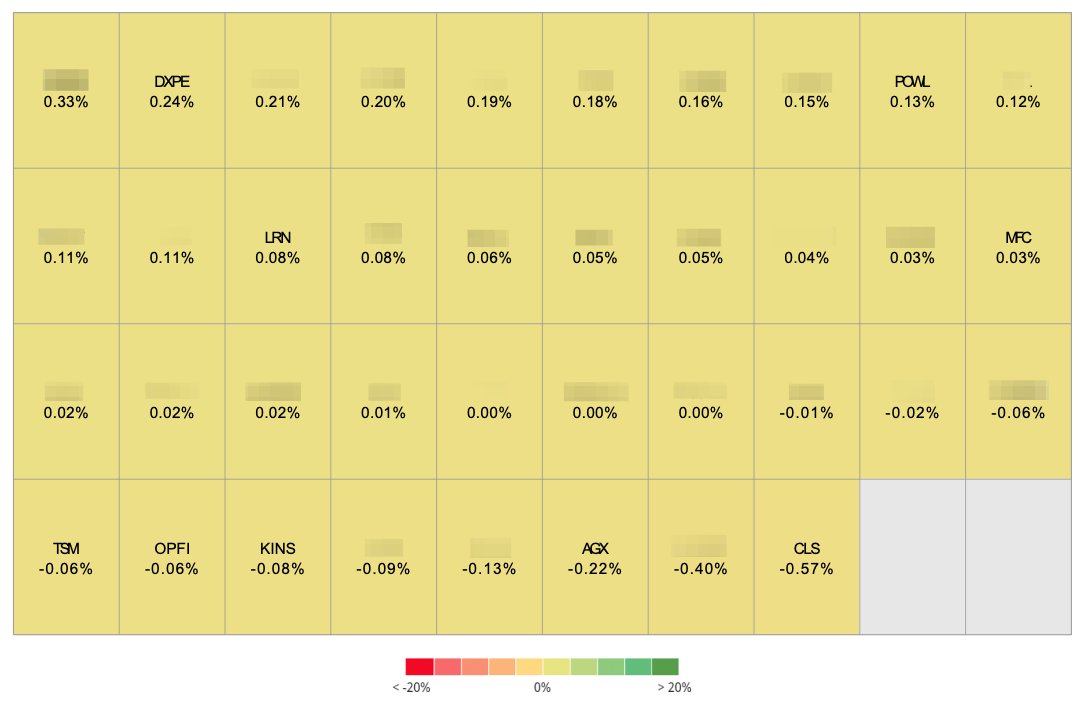

Contribution by Position

(For the full breakdown, see Weekly Stock Performance Tracker)

+24 bps DXPE 0.00%↑

+13 bps POWL 0.00%↑

+8 bps LRN 0.00%↑

+3 bps MFC 0.00%↑ (TSX: MFC)

-6 bps TSM 0.00%↑

-6 bps OPFI 0.00%↑

-8 bps KINS 0.00%↑

-22 bps AGX 0.00%↑

-57 bps CLS 0.00%↑ (TSX: CLS)

That’s it for this week.

Stay calm. Stay focused. And remember to stay sharp, fellow Sharks!

Further Sunday reading to help your investment process: