Weekly #39: TSMC Earnings Beat Again & Why Most People Misunderstand Fundamental Analysis

Portfolio +10.5 YTD. Everyone talks about fundamental analysis. Few actually do it right. TSM just crushed earnings.

Hello fellow Sharks,

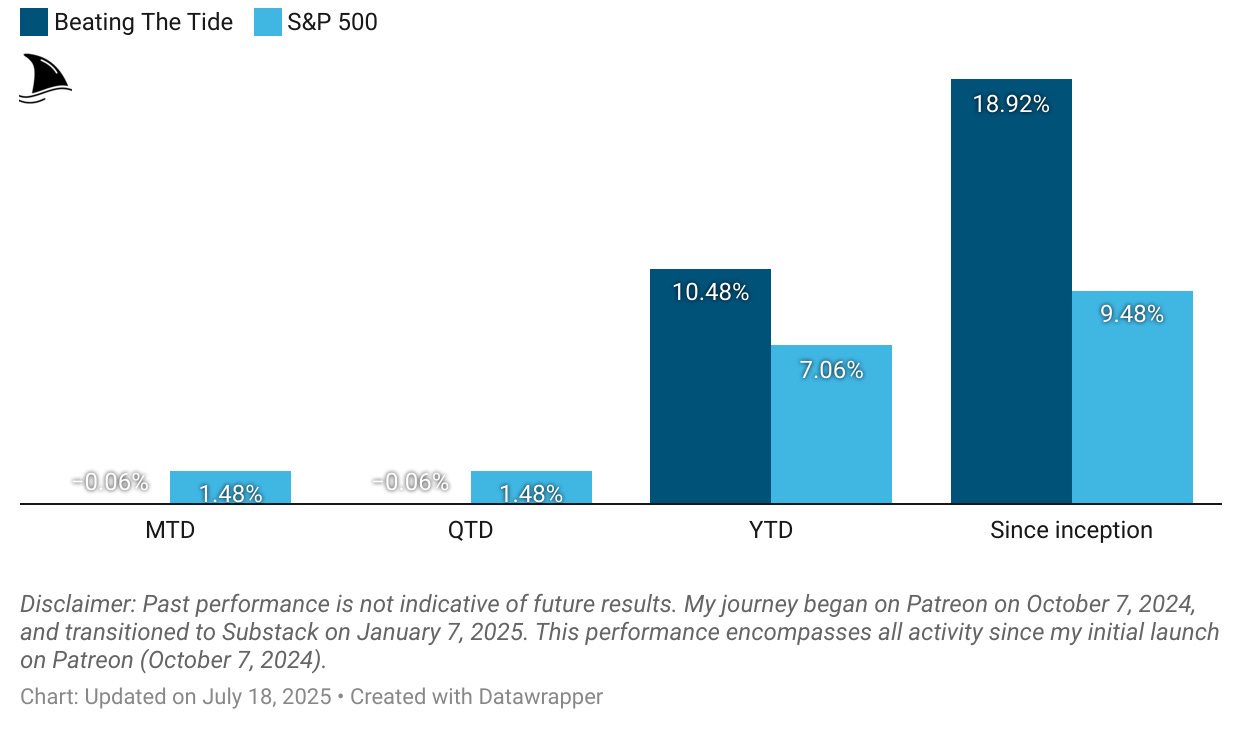

Our YTD performance just ticked up to +10.5%, maintaining a 2-to-1 lead over the S&P 500 since starting this newsletter. (If you want to skip ahead to the Portfolio Update, click here.)

This week, I break down TSMC’s blowout Q2 2025 earnings and explain why I’m still bullish even after the run-up.

But the real centerpiece is this week’s Thought of the Week, where I dig into a topic I care deeply about: what fundamental analysis really means. A lot of people talk about it… very few actually do it right.

Hope you enjoy the read and as always, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

~ George

Table of Contents:

TSM’s Q2 2025 Earnings: Another Quarter of AI-Fueled Outperformance

Thought Of The Week: Fundamental Analysis Isn’t What You Think

TSM’s Q2 2025 Earnings: Another Quarter of AI-Fueled Outperformance

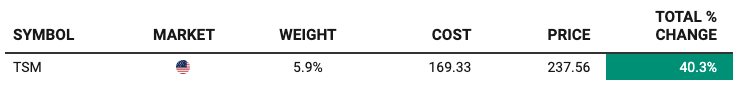

As you know from all my posts since late last year, I’ve been consistently bullish on TSMC (TSM 0.00%↑). On March 13, I sent a trade alert to paid subscribers explaining that I was increasing our position in TSM every week.

As a result, we increased TSM from around 2% of our portfolio to 5.9%, simultaneously bringing our average cost basis down from $196 to $169 by buying significantly around the $145 level.

Another Stellar Quarter

Well, TSM has done it again. Reporting another exceptional quarter driven largely by surging AI and HPC demand.

In Q2 2025, TSM reported:

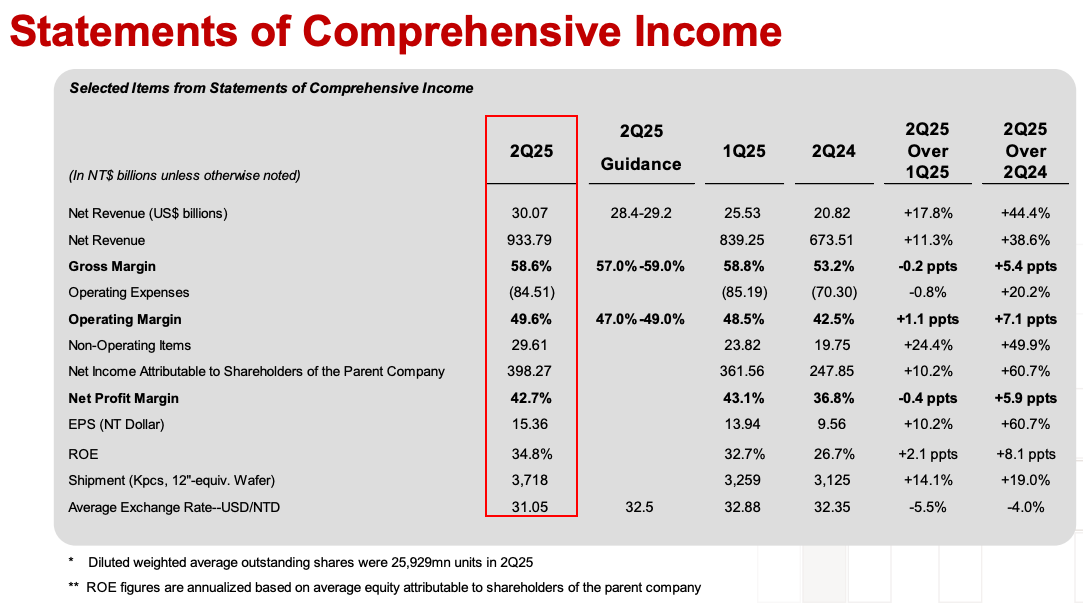

Revenue of $30.1 billion, up 44.4% y/y and up 17.8% sequentially.

Net income of $398.3 billion NT (~$2.47 per ADR), a stunning 60.7% increase y/y.

Gross margin at 58.6%, slightly impacted by unfavourable FX and margin dilution from ramping their overseas fabs, particularly in Arizona.

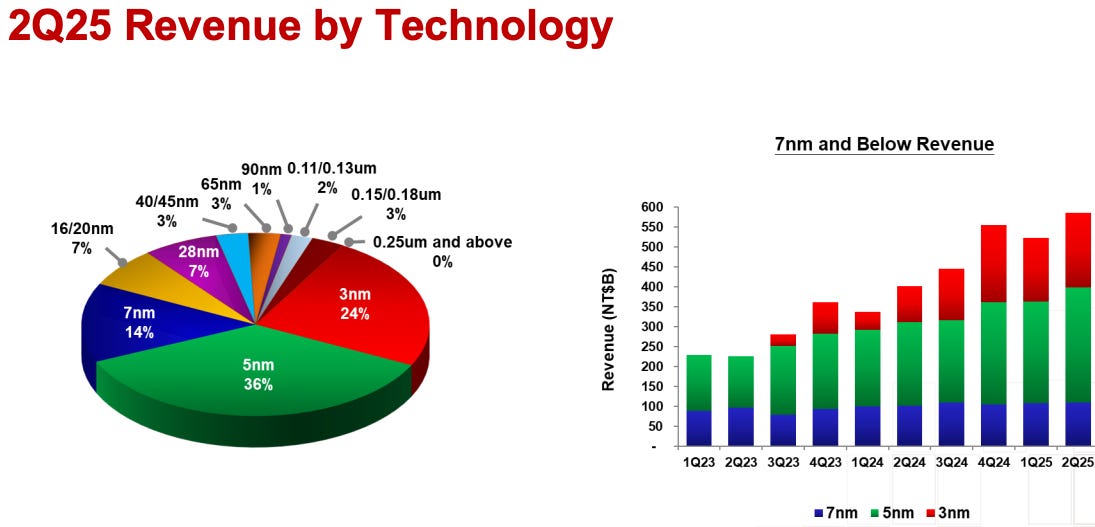

Earnings beat analysts’ expectations significantly, highlighting continued strength in advanced technologies like the 3-nanometer (24% of wafer revenue) and 5-nanometer nodes (36% of wafer revenue).

Advanced technologies overall (7nm and below) contributed 74% of wafer revenue.

Driving Factors Behind TSM’s Results

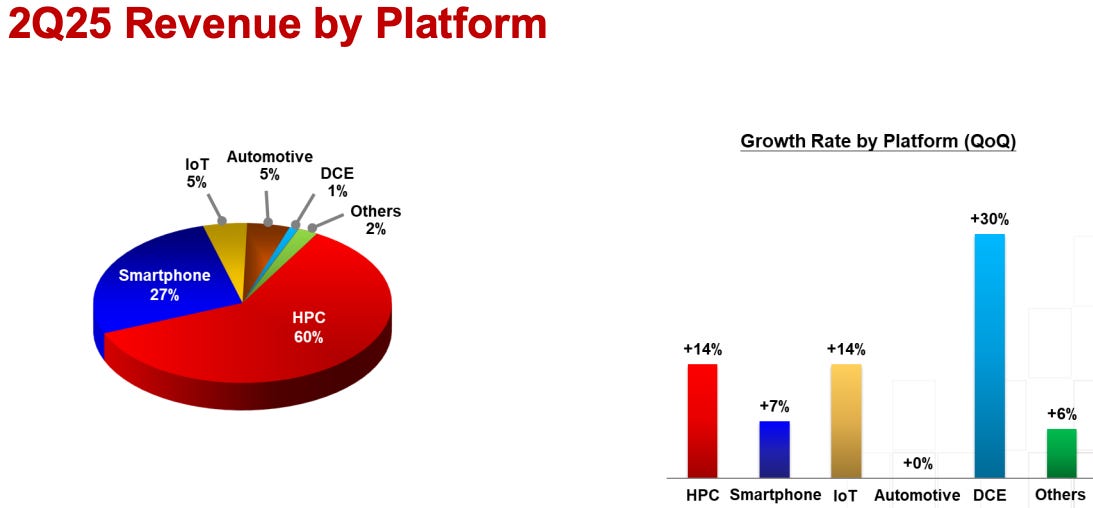

Demand for advanced semiconductor nodes (especially for AI and HPC applications) continues to be robust, supporting higher-than-expected utilization of TSM’s leading-edge manufacturing capabilities.

Some key insights:

Strong AI & HPC Demand:

AI-driven applications have been a clear catalyst. Data centers, cloud computing, and generative AI continue to fuel TSM’s high-growth segments. In Q2 alone, HPC platform revenue surged 14% sequentially, making up 60% of total revenue.

Advanced Node Adoption:

The 3nm node contributed significantly to revenue, reflecting rapid adoption and sustained premium pricing. This is expected to continue into the second half of 2025.

Geographical Expansion:

TSM’s first Arizona fab, which entered high-volume production in Q4 2024, is ramping up smoothly, though slightly dilutive to margins initially. The second Arizona fab (using 3nm tech) has completed construction, and production schedules are being accelerated due to strong customer demand.

Forward-Looking Guidance

TSM remains confident in its growth trajectory despite macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainties. Management has raised full-year 2025 revenue growth guidance from mid-20% to around 30% in USD terms, citing continued strength in AI and HPC demand. Q3 2025 revenue is expected to be between $31.8 billion and $33 billion, marking a 38% y/y increase at the midpoint.

However, TSM did flag potential challenges:

FX headwinds (appreciation of the NT dollar vs. USD) could impact gross margins negatively by around 260 basis points in Q3.

Ramp-up costs from overseas fabs (particularly Arizona and Kumamoto) will continue affecting margins in the short-term but are expected to moderate as utilization scales up.

My Take

My fair value remains $338 per ADR (see valuation), but I’ll be revisiting that in the coming weeks to see if an update is warranted. The market still seems to undervalue TSM, overly discounting tariff and geopolitical risks, while underestimating the powerful secular tailwinds from AI and HPC.

TSM’s 2nm node, set to ramp later in 2025, along with follow-on innovations like N2P and A16, represent major long-term growth drivers. These advances will help TSM maintain both its technological edge and pricing power for years to come.

What’s Next?

TSM’s strategic roadmap remains promising. Management reaffirmed ambitious expansion plans, including multiple new fabs across Taiwan, the U.S., Japan, and Europe.

Final Thoughts

TSM continues to deliver impressive growth and profitability despite near-term headwinds. This is a testament to its technological moat, strategic positioning, and the strength of secular growth in semiconductors.

I’m keeping a close watch on FX headwinds and geopolitical dynamics, but remain firmly bullish on TSM’s long-term prospects. It’s one of the best-run companies globally.

If you need a refresher on my investment thesis for TSM, here is the deep dive:

Thought Of The Week: Fundamental Analysis Isn’t What You Think

Whenever I listen to talking heads on TV, I remind myself that “every hammer sees every problem as a nail”. Knowing that people have their own agendas, I try to take what they say with a grain of salt.

Please keep that in mind when reading this week’s thought. I am a big proponent of fundamental analysis as it has served me well for more than a decade, and I see other ‘investing’ approaches as pure speculation and gambling.

I leave gambling for the casino, and my go-to gambling is blackjack 🙂

Just as I swear by fundamental analysis, there are people out there who believe the holy grail of investing is something else entirely. Some employ obscure approaches, others look to the stars, and still others swear by technical analysis. A couple of weeks ago, I ran into one of them (a person that swears by technical analysis).

I’m using our conversation to highlight a common misconception about what fundamental analysis actually is and where people often get it wrong.

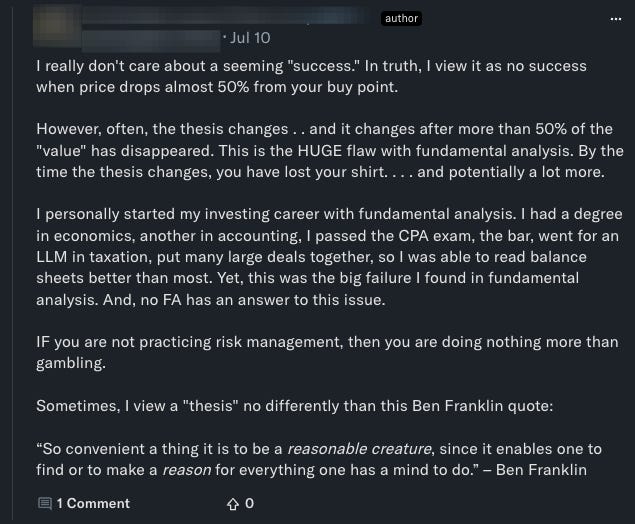

For context, he had posted something claiming that fundamental analysis (which he abbreviates as FA) is flawed. His argument didn’t hold up, so I replied. That kicked off a back-and-forth, and eventually, he posted the comment below:

When I read it, I got it. We were speaking different languages.

How can we agree on what fundamental analysis is if we’re working off totally different definitions of FA?

Like many others, he seemed to think that if you can decipher financial statements, then you’re doing fundamental analysis. He listed off his credentials — degrees in economics, accounting, taxation, and passed the bar — and made it sound like that alone made him a fundamental investor.

But in reality, everything he mentioned just qualifies him to read the numbers and understand macro trends. That’s useful, but it’s not the whole picture.

Yes, reading financial statements and understanding the numbers is important. But it’s secondary.

At its core, fundamental analysis is about understanding the company, its strategy, management, products or services, and the industry it operates in, inside and out.

As simple as that.

So let me break it down.

Fundamental Analysis: More Than Just Numbers

Fundamental analysis is often defined as a method of determining a stock’s intrinsic value by examining a company’s financials and other metrics. That means digging into things like earnings, assets, and growth rates to decide what a company is worth.

Fundamental analysis is commonly contrasted with technical analysis (which focuses on price charts and patterns). But limiting the definition of fundamental analysis to “reading financial statements” is only scratching the surface.

Yes, financial statements are an important piece of the puzzle. However, fundamental investing isn’t a rote accounting exercise; it’s more like detective work. It’s about understanding the story of the business behind those numbers. The numbers tell you what has happened; a true fundamental investor wants to know why it happened and what’s likely to happen next.

That means looking far beyond spreadsheets.

It means asking:

What does this company actually do to make money?

What’s special about it?

Who runs it, and can I trust them?

What’s happening in its industry?

These are the questions that drive real fundamental analysis, and the financial figures serve to back up the answers.

Think about it this way: if you’re evaluating a restaurant, the income statement might show the profit margins and revenue growth, but the fundamental insight comes from tasting the food, observing the customer line at dinnertime, and maybe even chatting with the chef.

In investing, it’s similar. You want to “taste” the product or service, gauge customer enthusiasm, and understand the competitive landscape. Only then do you crack open the annual report to see if the financial results align with what you’ve observed. Fundamental analysis is first and foremost about understanding the business itself, with the numbers used as a tool to quantify and confirm that understanding.

Understanding the Business Inside Out

To truly grasp a company’s prospects, you need to know it inside and out, almost like you were going to buy the whole business. This goes far beyond poring over quarterly earnings.

It involves studying the qualitative fundamentals: the company’s products or services, its strategy, its management team, its competitive advantages, and the industry dynamics it faces.

Business Model & Strategy

What exactly does the company do to earn money?

How does it operate, and how does it plan to grow?

A fundamental investor wants to understand the company’s value proposition: why customers choose it over the competition.

Is it a low-cost provider like Walmart, or a premium brand like Apple?

Does it rely on one-time sales, subscriptions, advertising, or something else?

Knowing the business model helps you project where future revenues and profits could come from. It also helps you spot threats, e.g., if the model is outdated or easily disrupted.

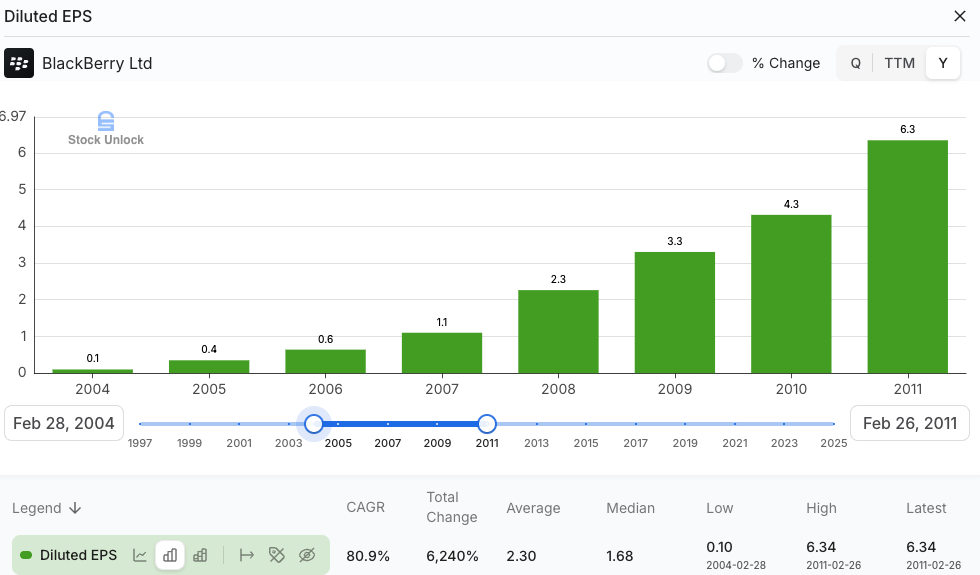

A classic case is BlackBerry vs. the iPhone:

BlackBerry’s model was built around hardware plus secure enterprise messaging — great at the time — but Apple redefined the market by turning the phone into a full-blown app platform and consumer-first ecosystem. If you were only looking at BlackBerry’s past financials, you might have missed that its entire business model was about to be steamrolled.

Understanding the strategy and business model is crucial to foresee these shifts before the numbers catch up.

Industry & Market Context

No company exists in a vacuum. Fundamental analysis means zooming out to the industry level.

What trends are driving or hindering the sector?

Is the overall pie growing or shrinking?

How tough is the competition?

Consider a company like Zoom before the pandemic versus now. The broader context (a sudden need for remote communication) drove its fortunes. An industry analysis can reveal whether a company is sailing with the wind at its back or rowing upstream against a current.

Great fundamental investors study supply and demand in the market, regulatory environment, technological changes, and consumer trends that could affect the company’s future. The classic fundamental approach always included checking macroeconomic factors and industry trends to see if the company is positioned for success.

Competitive Advantage (Moat)

Does the company have a sustainable edge over competitors?

The ‘moat’ is something that protects a business from being overtaken by rivals. This could be a strong brand (like Coca-Cola’s brand dominance), network effects (like Facebook’s social network where everyone is because everyone else is), patents or unique technology, cost advantages, or high switching costs for customers. I break these down in detail in Moats 101: The Ultimate Guide to Competitive Advantages in Investing.

What would stop a new competitor from stealing their customers tomorrow?

If you find a compelling answer, that’s a sign of a solid fundamental foundation. If you don’t, the company might be vulnerable despite what last year’s profit margins show. Competitive advantage is a core part of fundamental analysis. So much so that I’d rather invest in a great company with a moat at a fair price than a mediocre company at a cheap price.

Management Quality

The smartest strategy or most dominant market position can be squandered by poor leadership. That’s why fundamental analysis puts significant weight on who is running the company.

Has the CEO been a good steward of shareholder capital?

Do they make smart decisions on investments, acquisitions, and expenses (in other words, do they have a savvy capital allocation strategy)? Speaking of capital allocation, I just published a primer on capital allocation (The Ultimate Primer on Capital Allocation: A Shareholder’s Guide to Spotting Great CEOs).

The capital allocation strategy speaks volumes about management’s priorities and competence. The truth is, even the best business model is doomed if the leaders can’t execute it well.

We try to glean management quality from annual shareholder letters, earnings call transcripts, interviews, and the outcomes of their decisions.

Are they candid with shareholders when things go wrong, or do they hide bad news?

Do they have a clear vision for the future?

Products & Customers

This might sound obvious, but sometimes analysts get so buried in spreadsheets that they forget to consider whether the company’s product is actually any good! Fundamental analysis means trying the product or service yourself if possible, or hearing from actual customers.

If it’s a restaurant chain, go have a meal there; if it’s a software company, read user reviews (or demo the software if possible). A strong customer value proposition usually translates into good financials eventually. Conversely, if customers are consistently unhappy or a product is falling out of fashion, that’s a red flag that no rosy balance sheet can cover up for long.

Peter Lynch advocated “invest in what you know.” He meant that if you notice a company’s stores are always packed with shoppers and you love its products, you might be onto a good investment before the Wall Street analysts catch on. Lynch’s approach highlights that everyday insights, like observing consumer behaviour, can be just as important as formal analysis. He noted that individual investors often have an edge with local knowledge: noticing great products or services in their daily lives before they become obvious in the financials.

Of course, once you spot such a company, Lynch advised to “crunch some numbers” to make sure the company is actually profitable and well-run. But the spark starts with understanding the product and its market appeal.

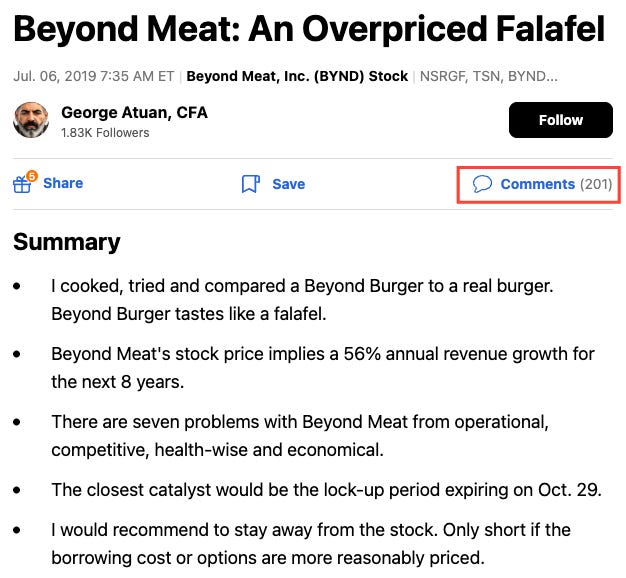

An example that comes to mind is my short thesis from 2019 titled Beyond Meat: An Overpriced Falafel (BYND 0.00%↑) back when the stock was trading at $152, just for context, it’s now at $3.48.

Yes, I dug into the financials, but that was just one piece of the puzzle. I also cooked, tasted, and compared the burger to a real one. On top of that, I looked closely at the business model, especially their co-packing agreements, which turned out to be a key weakness. If you go back and read the thesis, you’ll see how deep I went on that one… and well, it paid off.

The Role of Financial Statements (Important, But Secondary)

Now, after emphasizing that fundamental analysis is more than numbers, let me be clear: the numbers do matter!

I’m not suggesting you ignore the balance sheet or stop reading SEC filings. Reading financial statements is an essential skill in investing. It’s part of how you “trust but verify” the story you’ve built about a company. (If you need a primer on reading the 10k and proxy statements, check out The Art (and Science) of Reading 10-Ks and Proxy Statements.)

Once you feel you understand the business qualitatively, you turn to the financials to answer questions like:

Is this company actually profitable?

How fast are revenues growing?

Are there any looming risks on the balance sheet (like too much debt)?

The financial statements provide the factual grounding for your thesis.

The income statement will show you revenues, expenses, and profits over time, revealing trends like expanding profit margins or, conversely, rising costs that could indicate trouble.

The balance sheet will tell you if the company has a strong cash cushion or if it’s drowning in debt. Read my primer on the Balance Sheet.

The cash flow statement will reveal if it’s actually generating real cash or just accounting profits. These are important because even a great business idea can be a bad investment if the finances are mismanaged. Read my primer on the Cash Flow statement.

However, and this is the key point, financial statements are largely backward-looking. They tell you what happened last quarter or last year. We’re trying to figure out what’s going to happen in the future. That’s why understanding the business comes first.

If you just blindly buy stocks that have good past financials without understanding the business trajectory, you could walk straight into a value trap.

Value trap is a term for a stock that looks cheap by the numbers (low P/E, solid balance sheet, etc.) but is cheap for a good reason, often because the business model is broken or the industry is in decline.

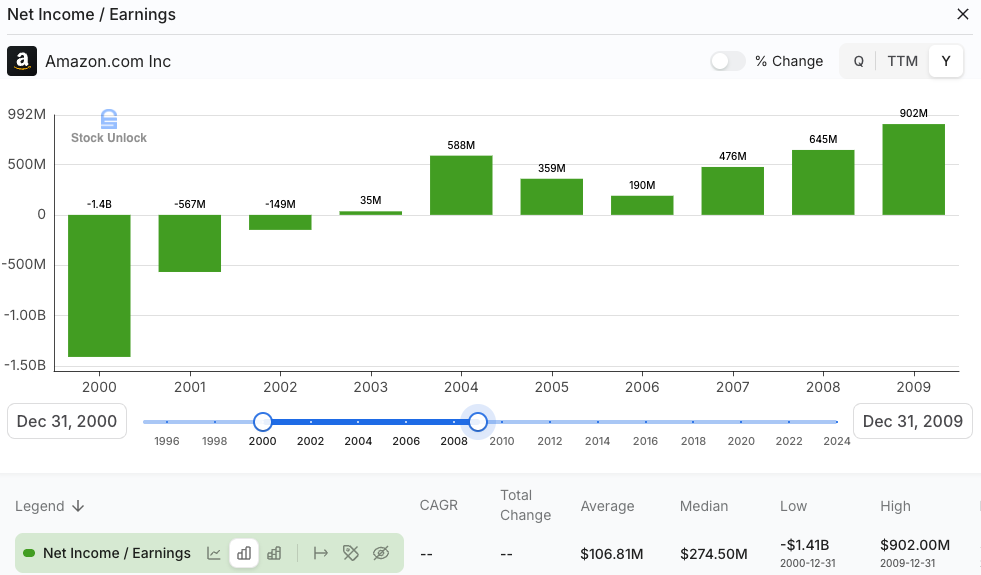

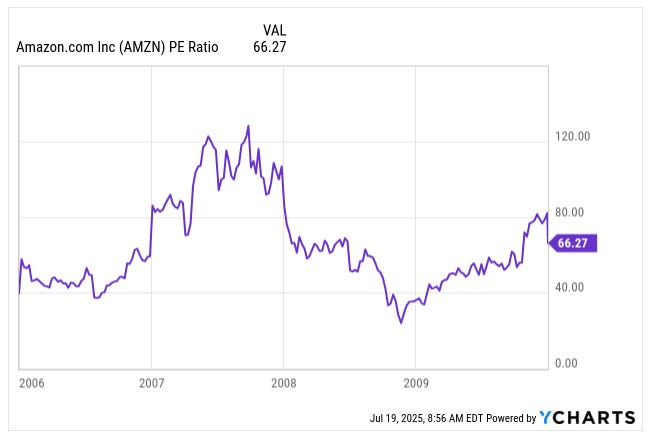

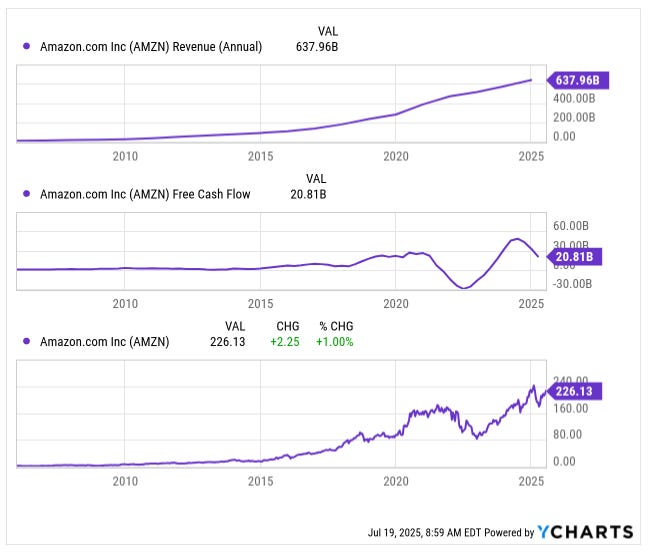

Think of Amazon in the early 2000s: by traditional metrics (profits, P/E ratio), it looked awful.

Barely any earnings. Sky-high valuation.

The first time I looked at Amazon was back in 2008 for an MBA assignment. I got an A on the paper, as it turns out, I was pretty good at deciphering financial statements.

But my sell recommendation?

Way off.

I didn’t truly understand the business model, nor did I grasp the scale of the e-commerce trend. At that point, I don’t think I’d even made a single online purchase with my credit card. I was still nervous about the whole “internet security” thing. (Though honestly, that might’ve been 2004… It’s all a blur now.)

The ones who really understood Amazon’s vision of e-commerce dominance, its fast-growing customer base and expanding logistics network recognized that the company wasn’t just chasing profits. It was reinvesting aggressively to build an empire.

That qualitative insight proved correct, and eventually the financial results (massive revenue and cash flow growth) vindicated the believers.

In hindsight, the fundamentals were there all along (strong leadership, huge market opportunity, customer obsession), even if the financial statements of the time didn’t yet reflect it.

So, reading financial statements is a necessary step, but it’s a second step. And importantly, you don’t need to be a world-class accountant or have a CPA to do this effectively.

You do need a basic literacy in accounting. The ability to read an annual report, understand key metrics, and spot red flags (How to Spot Red Flags in Stocks — An Ounce of Skepticism is Worth a Pound of Future Regret). My primers are sufficient and free. If you need the degree, I can send you a diploma from the school of Beating The Tide, just let me know 😉.

Great Investors Think Like Owners (Not Accountants)

This brings me to an important point: the investors with outstanding track records are often those who think like business owners. They immerse themselves in understanding the companies they invest in, almost as if they were going to run those companies.

They are not, by and large, winning because they can do arcane accounting tricks or outsmart others in parsing footnotes (although a basic mastery of accounting is vital to avoid mistakes). Instead, they win because they have insight into the business. Insight that others in the market might not have, or might not bother to attain.

Consider Warren Buffett. He’s famous for many reasons (read 10 Timeless Investing Lessons from Warren Buffett), but one of his core investing tenets is “buy a piece of a business, not a stock.” Buffett reads financial statements religiously (he often says accounting is the language of business), but what truly sets him apart is his ability to identify wonderful businesses.

He stays within what he calls his “circle of competence,” investing in industries and companies he understands deeply. Buffett once explained that an investor doesn’t need to be an expert on everything, just the things they choose to invest in:

You don’t have to be an expert on every company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.

In practice, this means Buffett has often passed on investments that others were hyped about (like tech stocks during the dot-com era) because they were outside his understanding, and that discipline saved him from losses when the tech bubble burst. He instead stuck to things like Coca-Cola, insurance, banking, that is, businesses he could wrap his head around.

The result? Decades of solid returns.

Lynch famously said,

Investing is simple, but it’s not easy.

The simple part is that you don’t need a PhD in finance to do it; often, your intuition and knowledge about an industry can guide you to good ideas. The not easy part is having the patience and discipline to research thoroughly and not get swept up by hype.

He credited much of his success to finding companies that he personally or his family encountered, like Dunkin’ Donuts or Walmart (WMT 0.00%↑) in the early days, and then doing the homework to see if the stock was a bargain. He didn’t rely on some secret accounting formula; he relied on understanding the business opportunity better than others.

Many accountants or financial analysts do not automatically become great investors.

I’ve seen folks who could recite accounting rules in their sleep make poor investment decisions because they got too lost in minutiae or they fell in love with a stock’s cheap ratios while ignoring bigger issues.

On the flip side, I’ve known brilliant investors with liberal arts degrees or engineering backgrounds who approached investing by simply learning what makes a business succeed. They, of course, picked up enough finance know-how along the way, but they spend 80% of their time thinking about the business, and maybe 20% crunching the numbers (if that).

They think like owners:

If I owned this entire company, what would I worry about?

What would I focus on to improve it?

Where will it be in 5-10 years?

Those questions lead them to the factors that truly matter.

Play to Your Strengths

One theme I’ve repeated in many Beating The Tide issues is the idea of investing where you have a competitive advantage. Fundamental analysis works best when you apply it in areas you understand better than the average market participant. Read The Secret to Outsmarting the Market: Leverage Your Competitive Advantage in Investing.

For example, if you’ve worked in healthcare for 20 years, you probably have a feel for what makes a pharmaceutical company’s pipeline promising or which medical device company has a superior product. That’s knowledge not everyone has— that’s your edge.

You can apply fundamental analysis in that sector with a nuanced perspective, catching details others might overlook. Or maybe you’re a software developer and you might have insight into which tech companies have a truly innovative product versus just hype. Perhaps you’re an avid gamer, and you can tell which gaming company has the titles or platform that gamers are gravitating towards. These are all edges rooted in understanding an industry’s nuances.

Investing where you have this kind of advantage can greatly increase your odds of success. I’ve seen readers of this very newsletter capitalize on their professional knowledge, like a subscriber who works in the oil industry and could tell when oil service companies were undervalued because he knew contracts were picking up before it hit the headlines. Or a friend of mine who’s a veterinarian and uses her knowledge to invest in pet health and agriculture stocks. She understands that world deeply, so when she reads those companies’ reports, the jargon makes sense and she can spot BS or overly conservative guidance that others might not catch.

On the flip side, when you stray into sectors you know nothing about, you’re playing on someone else’s turf. I confess, in my early days, I got burned a couple of times investing in companies I thought were “cheap” by the numbers in industries I didn’t really get. I learned that if you don’t know what a company’s jargon means, or you can’t explain how it makes money to a friend, you probably shouldn’t invest in it. These days, I stay within my circle.

So ask yourself:

What’s your circle of competence?

It could be one, two, or three sectors, and they don’t have to be flashy, high-growth areas; they just have to be spaces where you know more than the typical investor. It’s often tied to what you do professionally or a business model you’ve studied extensively. Invest there. Use your informational or analytical edge.

To be clear, having an edge doesn’t guarantee every pick will be a winner (nothing does… this is investing, after all, not magic). But it tilts the odds in your favour. And as fundamental investors, we’re always looking to tilt the odds our way, bit by bit. We don’t control the market, but we control what we focus on. So focus on where you can be “wise, and others are stupid,”1

What industry or area do you know really well, and are you leveraging that knowledge in your investing?

I’m genuinely curious what circles of competence are represented among readers.

Portfolio Update

This week, we experienced a pullback compared to the previous week.

Month-to-date: We’re flat (–0.06%) vs. the S&P 500’s +1.5%.

Year-to-date: Our lead has held strong. +10.5% vs. the S&P’s +7.1%, a gap of 340 basis points.

Since inception: We’re now up +18.9% compared to the S&P 500’s +9.5%. That’s almost 2x the market.

Portfolio Return

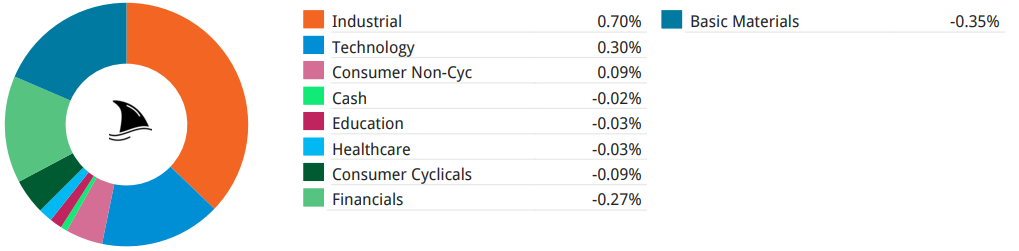

Contribution by Sector

Industrials and tech led the gains, offset by gold and financials.

Contribution by Position

(For the full breakdown, see Weekly Stock Performance Tracker)

+29 bps DXPE 0.00%↑

+24 bps TSM 0.00%↑

+18 bps POWL 0.00%↑

+13 bps KINS 0.00%↑

+4 bps MFC 0.00%↑ (TSX: MCF)

-1 bps LRN 0.00%↑

-4 bps CLS 0.00%↑ (TSX: CLS)

-9 bps AGX 0.00%↑

That’s it for this week.

Stay calm. Stay focused. And remember to stay sharp, fellow Sharks!

Further Sunday reading to help your investment process:

How I Earn $3,000-$7,000 a Month While Waiting to Buy Great Stocks Cheaper

The Art of Knowing When to Sell a Stock (And When to Sit Tight)

Quote by Charlie Munger

Your perspective on fundamental analysis - particularly the emphasis on understanding business models beyond just financial statements shows how operational realities drive investment outcomes. The cash flow focus naturally extends to working capital dynamics and trade credit cycles that TCLM examines in detail—might be worth a look for additional context.

(It’s free)- https://tradecredit.substack.com/