Why I’m Still Bullish on STRL After a +337% Gain

A deep-dive investment thesis on Sterling Infrastructure (STRL). I see at least a further 36% upside as the AI buildout fuels a multi-year growth story.

Building data centers is a fascinating, gritty business. For years, I had a front-row seat at Entel, where I was part of the team that built out our latest server farms. It’s a unique industry, a perfect blend of an old-world trade and a new-world purpose. One day you’re dealing with concrete, aggregate, and rebar, and the next you’re planning for high-density server racks, liquid cooling systems, and biometric security. It’s a world where a delay in pouring a foundation can ripple out and postpone the launch of a billion-dollar cloud service.

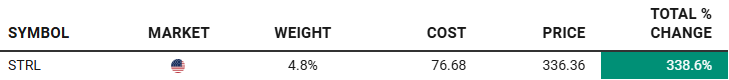

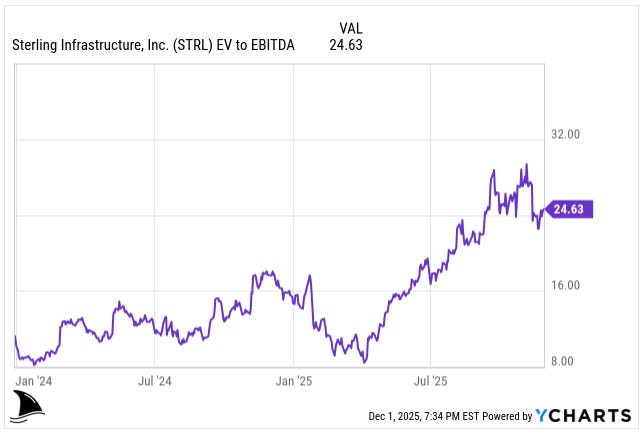

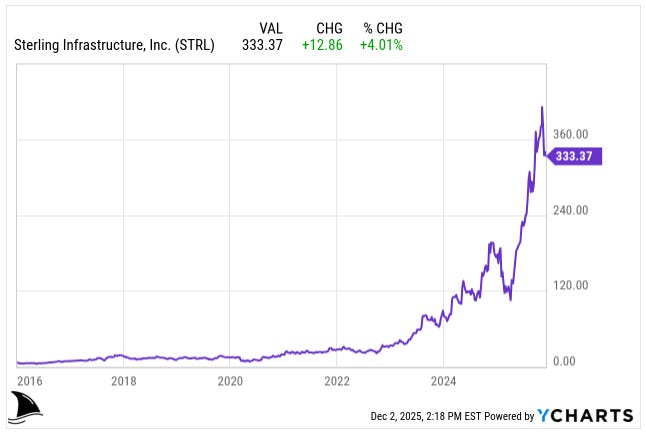

This background is what led me to Sterling Infrastructure (STRL 0.00%↑). When I first invested, it was a classic value play. The company was in the middle of a brilliant, underappreciated transformation from a low-margin road paver into a specialized site developer for exactly these kinds of mission-critical facilities. The market hadn’t caught on, and the stock was trading at a sleepy 9x EV/EBITDA.

That was then.

Today, after a more than 337% gain, the story is entirely different.

STRL is no longer a value stock; at a current EV/EBITDA multiple of 24.6x, it’s rich by any traditional measure.

My investment has evolved from a value play to a growth story.

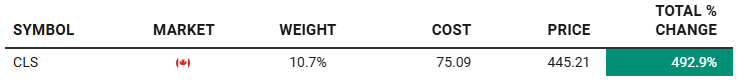

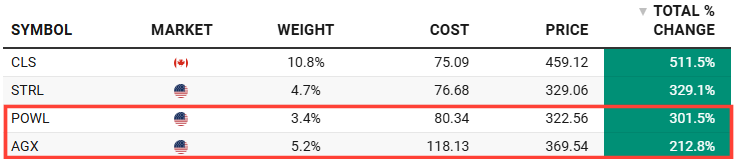

I’m usually uncomfortable with growth companies. They require a level of confidence in the future that can feel more like faith than analysis. But sometimes, the story is so clear and the tailwinds so strong that the risk is justified. I felt that way about my investment in Celestica (CLS 0.00%↑), another successful growth pick that has performed exceptionally well.

I feel that same conviction with STRL today.

My confidence isn’t based on hype. It’s grounded in the numbers I see on Sterling’s books, the plans I hear from its customers, and the secular demand that isn’t even in the pipeline yet.

The AI revolution requires a staggering amount of new digital infrastructure, and STRL is one of the few companies with the scale and expertise to prepare the ground for it. This isn’t a one-year trend; it’s a multi-year buildout. For that reason, even after its incredible run, my deep dive analysis leads me to a clear conclusion: I see at least a further 36% upside to a fair value of $455 per share. This is the story of that transformation, and why I believe the next chapter of growth is just beginning.

Because data center buildouts sit at the heart of my valuation for this leg of the STRL investment, I treat them as more than a passing tailwind. The entire upside case depends on how fast and how long this build cycle runs. That is why, in the Industry section, I go deep into the AI-driven data center boom itself, from the raw numbers on global and U.S. spend to the hyperscalers, REITs, and contractors driving it, and the bottlenecks and risks that could slow it. If the data center buildout holds, STRL’s runway holds.

The Elevator Pitch

I first bought Sterling Infrastructure when it was a cheap, misunderstood road builder at about 9x EV/EBITDA. Today, after a +337% gain and a richer 24.6x multiple, I still see about 36% upside to a fair value of $455 per share.

The reason is simple. Sterling has turned itself into an E-Infrastructure platform that prepares and powers sites for hyperscale data centers, semiconductor fabs, and distribution hubs, while its Transportation and Building businesses provide cash and stability.

The AI-driven data center buildout and the multiyear backlog in E-Infrastructure give it a long runway. Management has a strong track record of smart capital allocation, from exiting low-margin highway work to acquiring Plateau and CEC, and they have lifted ROIC into the high 20s.

My DCF already bakes in slower growth in the legacy segments, modest margin compression over time, and some normalization of valuation. The key risk is an AI or capex downcycle, but with this niche, balance sheet, and pipeline, I see STRL as one of the best ways to own the “picks and shovels” of the AI buildout.

Table of Contents:

Company History: From Paving Roads to Powering the Cloud

To fully appreciate the investment thesis for STRL, you have to understand where it came from. The company’s history is not just a timeline of events; it’s a case study in strategic transformation executed by a sharp and disciplined management team. This evolution is the foundation of my confidence in STRL’s future.

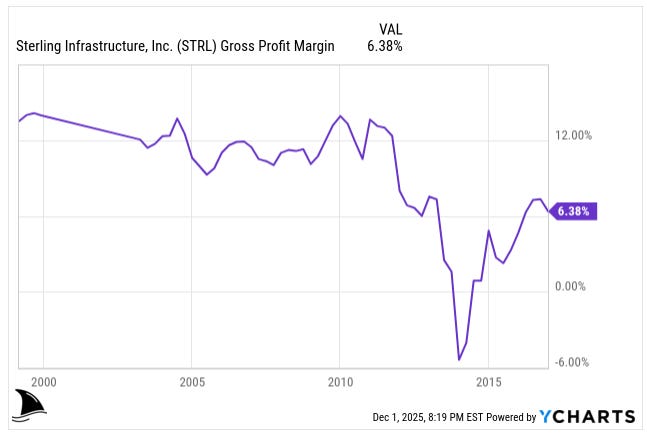

For years, Sterling was a low-margin, heavy civil construction business focused almost exclusively on low-bid heavy highway projects. This is a tough, commoditized business where you often win by being the cheapest, not the best. Before 2016, the company’s gross margins hovered around a meager 6%.

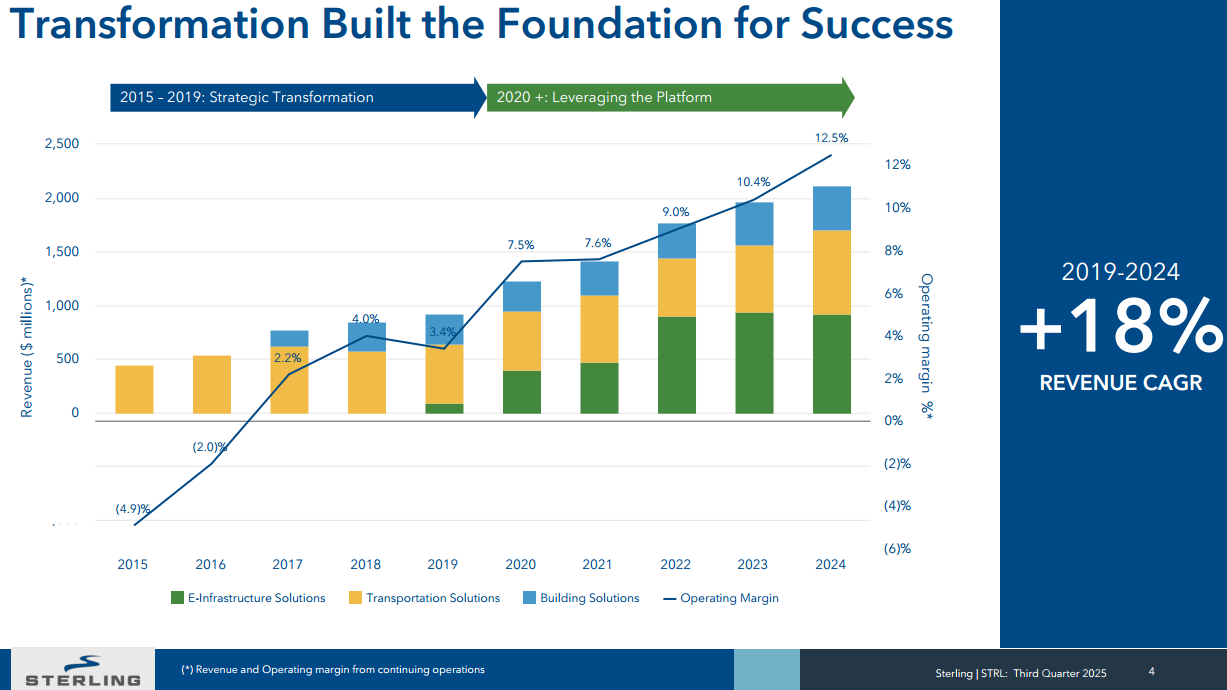

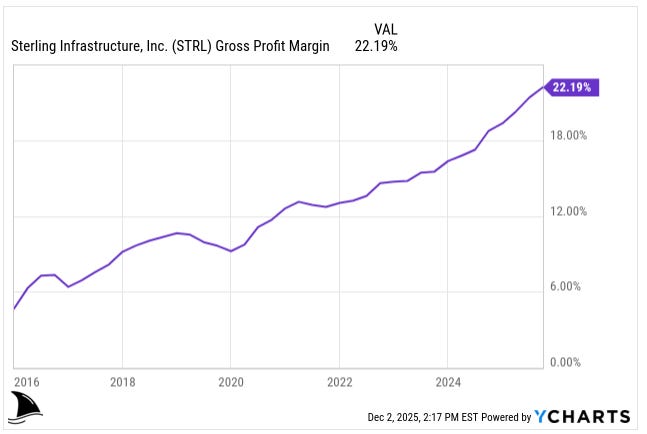

What impressed me most was the deliberate, multi-year strategy initiated in 2016 to “solidify the base” and “grow high margin products.” This wasn’t just talk. Management systematically began exiting the low-bid highway work that had defined the company for decades. That part of the business, which accounted for 79% of revenue in 2016, was deliberately shrunk to just 15% by 2024. This disciplined move had a direct and powerful impact on profitability. The company’s heavy highway backlog gross margin, which was stuck in the low single digits, improved to 9.6% by the end of 2020. This set the stage for a series of transformative acquisitions that reshaped the entire company.

Tealstone (2017): This was the first major step away from the old business model. The acquisition of Tealstone brought Sterling into the residential and commercial concrete market, establishing what is now the Building Solutions segment and providing the first taste of diversification into higher-margin work.

Plateau (2019): This was the pivotal move. The acquisition of Plateau vaulted Sterling into large-scale site development, creating the foundation for what would become its high-growth E-Infrastructure Solutions segment. This is where the company began building its reputation with the blue-chip technology and e-commerce clients that are now its primary growth engine.

CEC Facilities Group (2025): The most recent and, in my view, most significant strategic step yet. With the acquisition of CEC, Sterling moved “up the value chain.” Historically, STRL focused on site preparation (the “dirt work”), while peers like EMCOR (EME 0.00%↑) handled the actual building process, like electrical and fire safety systems. The CEC acquisition moves STRL from a site-prep specialist into an integrated partner. It can now compete for a much larger share of the total data center construction budget, directly challenging a new set of competitors.

This deliberate, step-by-step evolution has fundamentally changed how Sterling makes money and positioned it perfectly for the next decade of growth.

How Sterling Makes Money: The Three Engines

While Sterling reports as a single company, it’s essential to analyze it as a portfolio of three distinct businesses. These segments operate in different markets, serve different customers, and have vastly different growth prospects and margin profiles. Understanding this distinction is key, because one of these engines is now powering almost all of the company’s growth.

E-Infrastructure Solutions

This is the crown jewel and the company’s primary growth engine. This segment is responsible for large-scale, advanced site development services and, with the recent CEC acquisition, mission-critical electrical services. Its end-markets include data centers, semiconductor fabrication plants, manufacturing, e-commerce distribution centers, warehousing, and power generation. Its key customers are the titans of the digital economy: “hyperscalers, colocation providers,” and other blue-chip technology firms.

This segment is on fire. In the third quarter of 2025 alone, its revenue grew an astonishing 58%, and it consistently delivers the company’s highest operating margins. This is where the entire growth story for STRL lies.

Transportation Solutions

This is the company’s legacy business, focused on infrastructure projects like highways, bridges, airports, and rail. Its customers are primarily government entities, and its health is tied to public funding cycles. The segment benefits from the stable funding environment provided by the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA), which provides a solid baseline of work.

However, in line with its broader strategy, management is actively shifting this segment away from low-bid projects in Texas. This is expected to moderate revenue growth in the near term but should lead to healthier, more predictable margins over the long run.

Building Solutions

This segment provides concrete foundations and plumbing services for the residential and commercial housing markets, primarily in Texas and Phoenix. Its performance is cyclical and closely tied to the health of the housing market. Currently, it faces headwinds from higher interest rates and housing affordability challenges. While the company has prudently expanded its service offerings (adding plumbing via the PPG acquisition) and geographies, this segment remains sensitive to macroeconomic conditions.

While the Transportation and Building Solutions segments provide a stable foundation, it is the market dynamics of the E-Infrastructure segment that will determine Sterling’s future.

Industry Landscape: The AI-Fueled Data Center Gold Rush

I’ve been following how AI is reshaping the data center landscape, and it’s nothing short of a construction frenzy. Data centers are suddenly sprouting up like skyscrapers in a boomtown. This boom is driven by companies racing to train and run AI models, along with ever-growing cloud demand. As STRL’s outlook depends on the construction of data centers, I’ll explain what’s happening in the industry worldwide and in the U.S.

Skyrocketing Demand and Spending

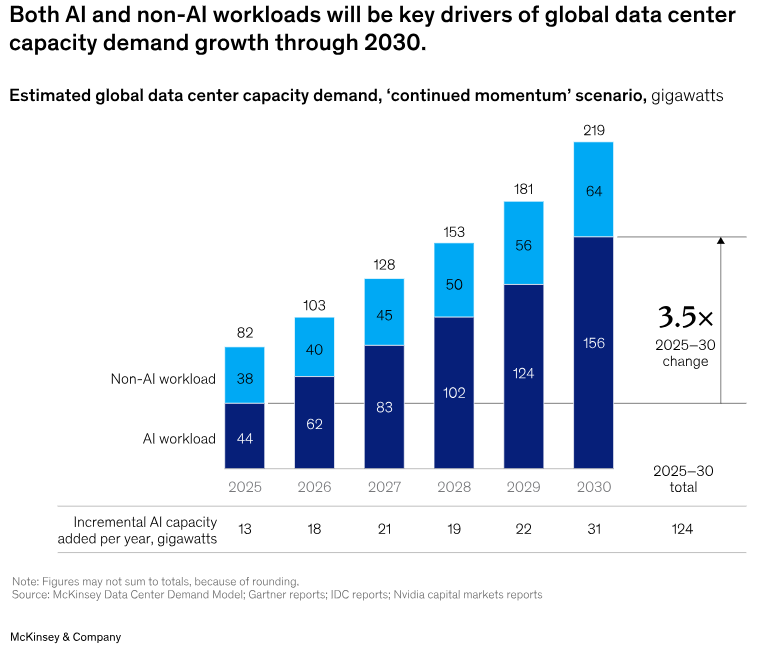

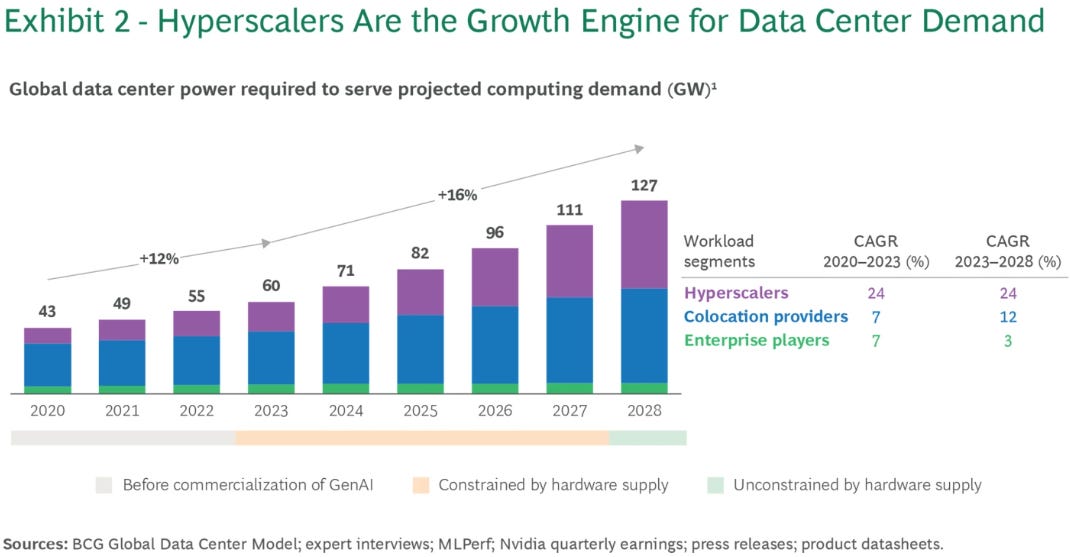

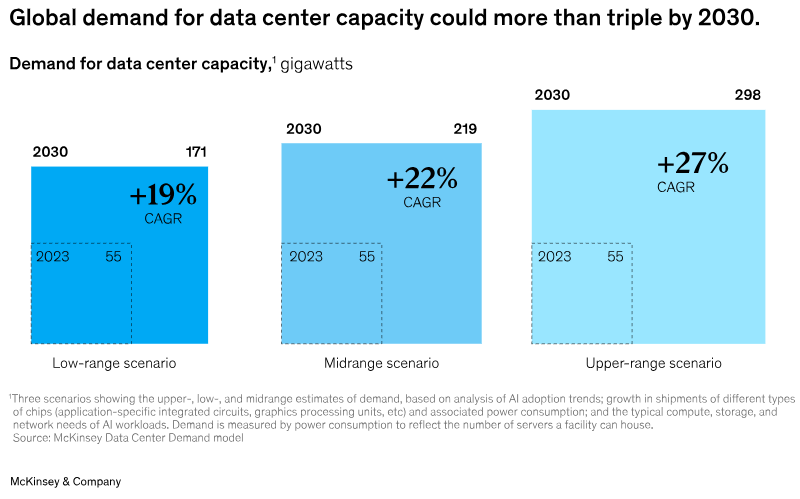

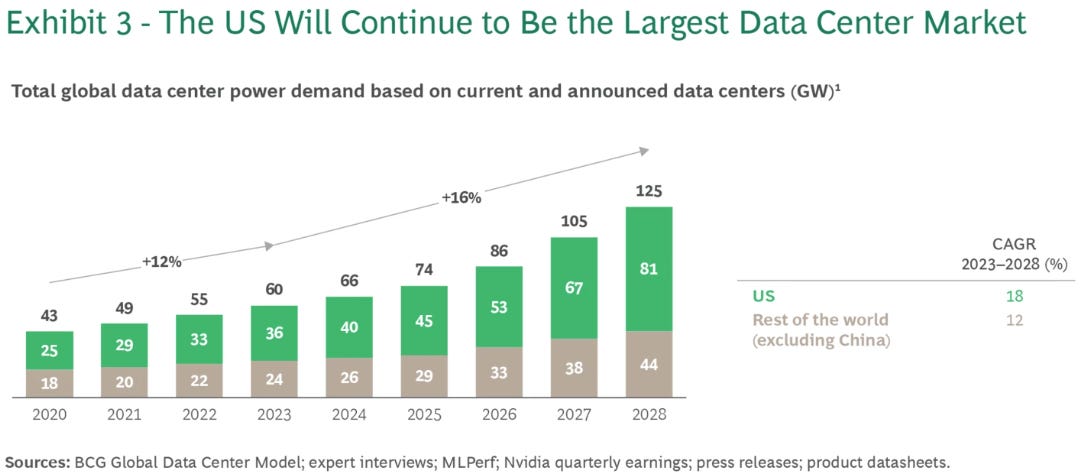

Data center demand has been surging as AI workloads explode. Researchers project data center power capacity could triple by 2030.

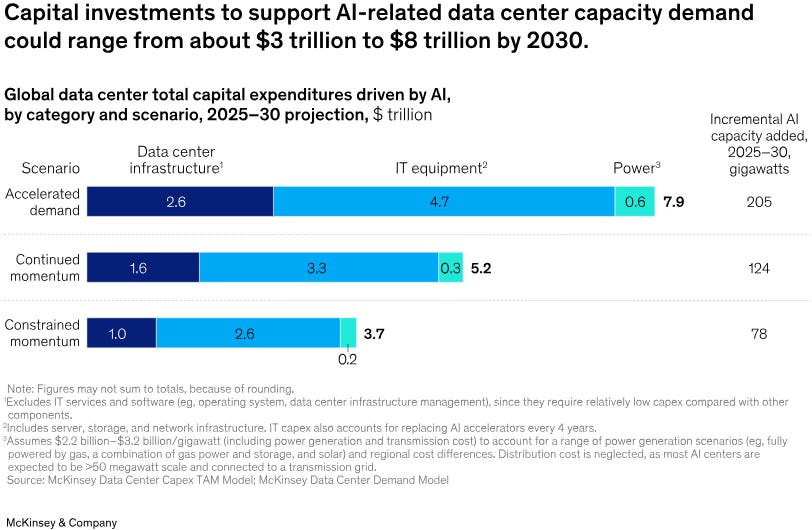

One McKinsey study estimates global data centers will need $6.7 trillion in capital spending by 2030 to keep up, with $5.2 trillion of that for AI-specific needs. In other words, nearly $7 trillion in total capex by 2030, driven mostly by AI.

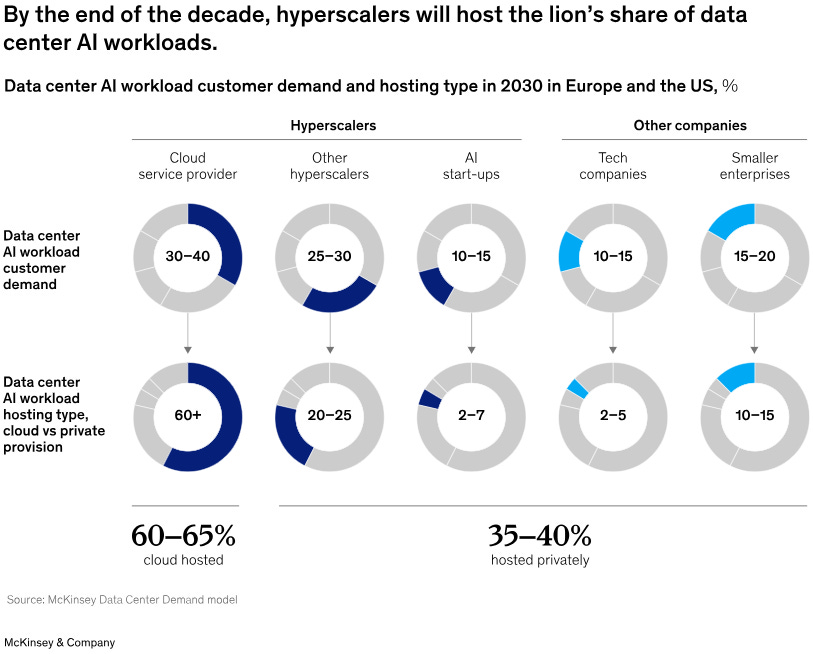

Hyperscale cloud providers will shoulder a huge slice of that.

BCG notes hyperscalers alone may spend $1.8 trillion in U.S. data center capex from 2024–2030.

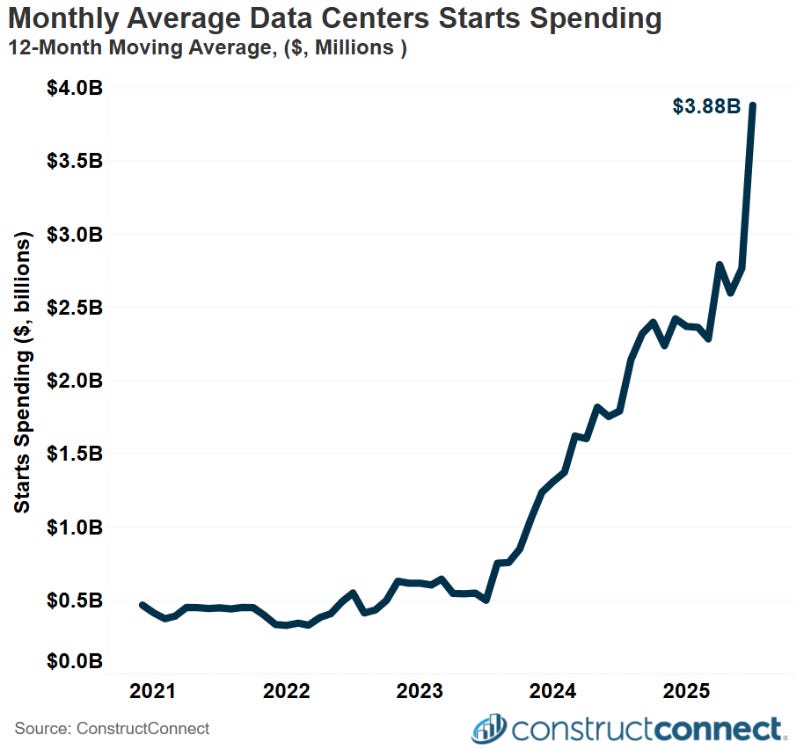

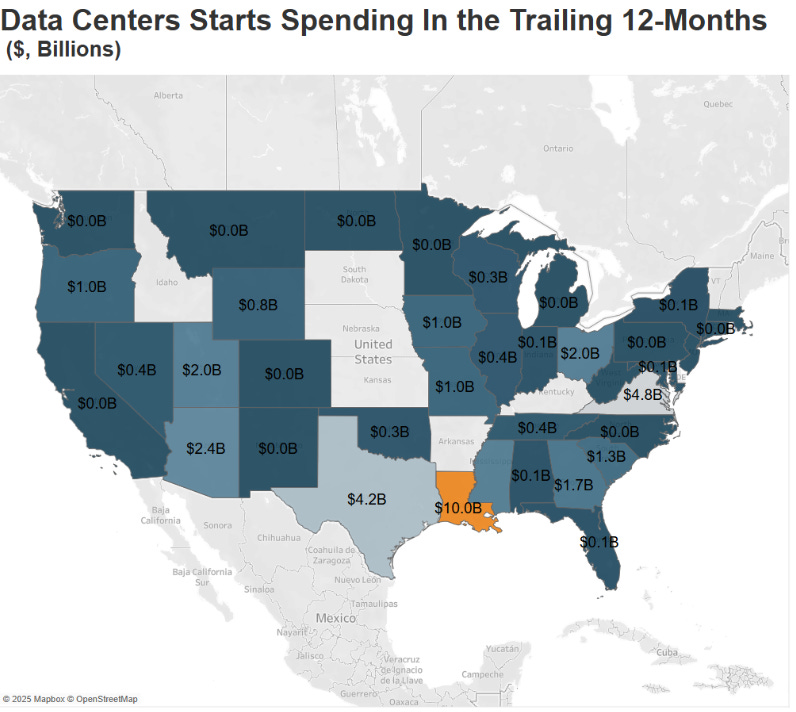

This means we’re building data centers faster and bigger than ever. For example, a construction tracker (ConstructConnect) reported July 2025 had $14 billion in data center construction starts, doubling the previous monthly record. As of mid-2025, U.S. data center construction spending was already $26.9B YTD, triple last year’s pace. At that rate, they expect to break $46B for 2025.

To put that in perspective, the total U.S. data center construction market is projected at $17–$29 billion per year over the next decade.

Demand is climbing at double-digit rates. One McKinsey model shows 19–27% annual growth in capacity needs from 2023–2030 globally.

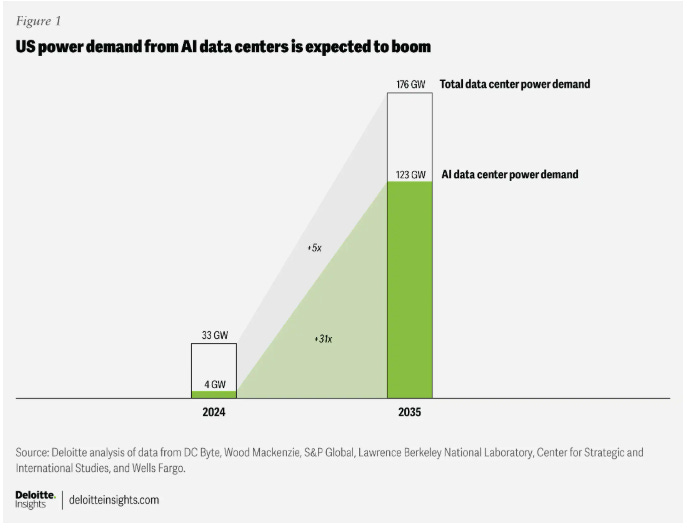

Also, Deloitte projects U.S. AI data center power demand alone growing 30-fold (to 123 GW) by 2035.

Roughly 70% of that growth is expected to come from AI training and inference. Cloud and hyperscale providers currently own over half of the world’s AI-ready capacity.

The picture is straightforward: AI and cloud are driving a gold rush in compute infrastructure. It’s like tech companies are in an arms race, building more and more “computer factories.”

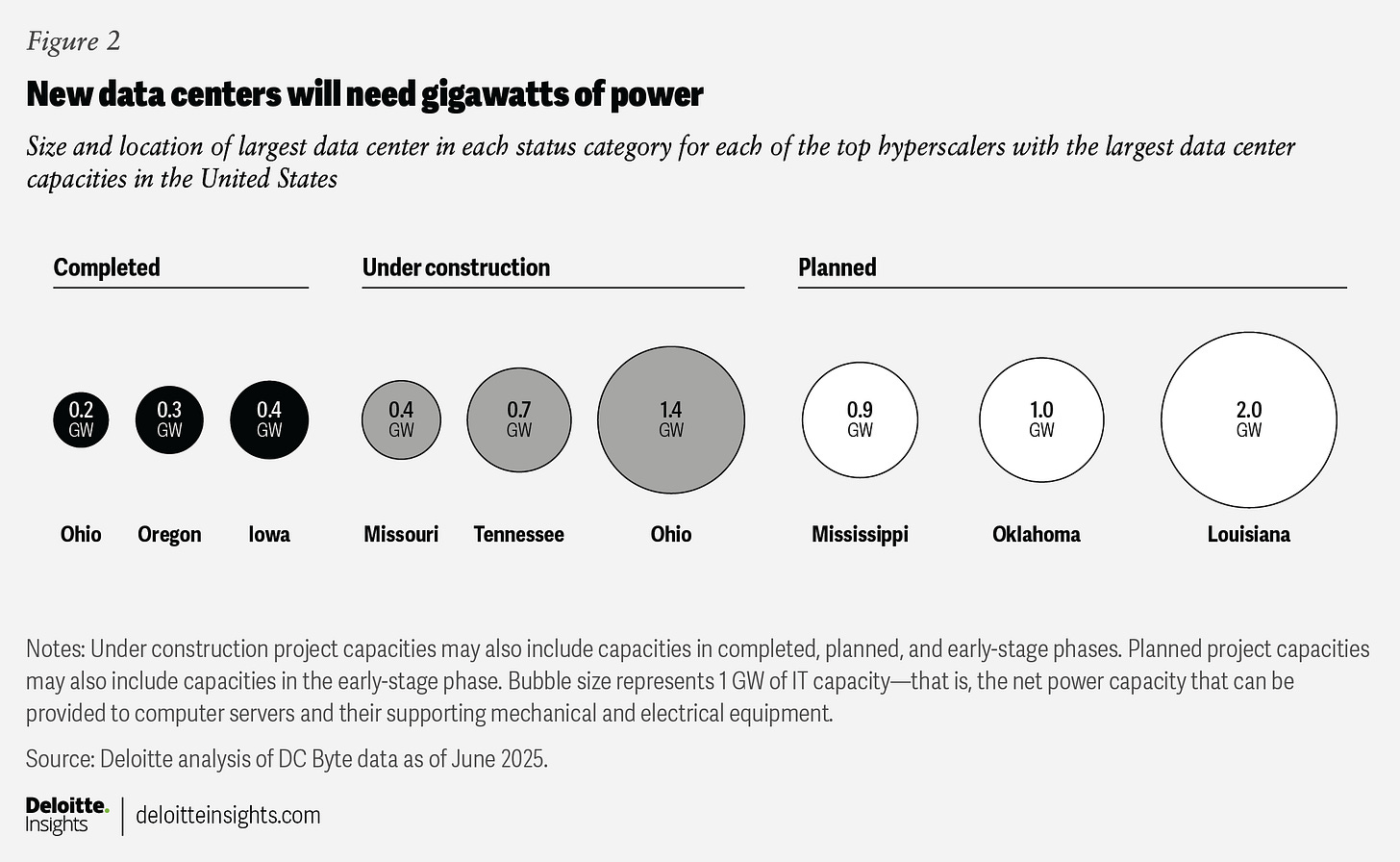

For example, each hyperscale AI data center these days might consume hundreds of megawatts, much larger than the 40–50 MW centers of the past. Note that leading hyperscale data centers are under 500 MW, but those under construction and planned may have up to 2,000 MW.

At that scale, individual facilities are nearly like cities of power-hungry machines.

Taken together, these trends mean data center construction is booming worldwide, with a particularly intense surge in the U.S. where many cloud giants are building. The U.S. share of global capacity is roughly 60% and rising, partly due to massive projects in places like Virginia, Texas, and the Midwest.

Tech Giants and Hyperscalers Leading the Charge

The surge is powered by a few major tech players. The hyperscalers1 are pouring billions into new facilities to train AI and serve cloud customers. As I showed in the previous section, cloud service providers are fueling most incremental demand for AI-ready data centers.

Microsoft (MSFT 0.00%↑), Amazon (AMZN 0.00%↑), Google (GOOG 0.00%↑), and Meta (META 0.00%↑) have publicly announced huge investment plans.

For example,

Microsoft told Congress it will spend about $80 billion in fiscal 2025 on AI-enabled data centers worldwide, with over half in the U.S.

Amazon’s cloud unit, AWS, announced a $50 billion investment to build dedicated AI/supercomputing data centers for U.S. government use.

Google said it will pour $40 billion into three massive new Texas data centers through 2027.

Meta pledged a $600 billion investment in U.S. infrastructure (including AI data centers) over three years as part of an aggressive strategy to build “the biggest data centers yet” for its AI ambitions.

These companies see these investments as giving them a strategic edge, much like early railroads or highways gave economic advantage. It’s literally “betting the ranch”: Meta said it is “aggressively front-loading capacity” so it’s ready for the most optimistic AI scenarios.

Their pledges underscore how much money is flowing into data centers: hyperscalers spent over $230 billion on capex in FY2024, projected up to $320B in FY2025.

A crucial part of the story is Nvidia (NVDA 0.00%↑). Nvidia’s sales numbers also highlight how big this is. For Q3 of its 2026 fiscal year (ended Oct 2025), Nvidia reported $51.2 billion in data-center revenue, up 66% from a year earlier. Nvidia’s CEO even said “cloud GPUs are sold out” and that “AI is going everywhere”.

In short, the skyrocketing demand for Nvidia’s chips is a proxy for the data center boom. Each major AI model training run can use tens of thousands of GPUs and consume as much power as a small city.

Each of these companies has also influenced geography. They compete to build in states offering incentives (like Virginia, Texas, Nebraska, etc.) and often pair DC expansion with clean energy deals. In all, by targeting different regions, they’re spreading demand across the country.

Data Center Operators and REITs

Beyond the tech giants, there are specialized real-estate companies and REITs that own and operate data centers (and lease them to tenants). The biggest include Equinix, Digital Realty, CyrusOne, and QTS. These firms develop, own, and rent space and power in their facilities.

Digital Realty Trust (DLR 0.00%↑) is the largest data center REIT. It operates over 300 data centers in 47 markets worldwide. In early 2025 its development pipeline was $9.3B, and it’s adding capacity fast (50 MW delivered with 83% prelease, and 219 MW underway, including a 200 MW project in Virginia). DLR focuses on big hyperscale builds; over two-thirds of its new leases in Q1 2025 were AI-related. It emphasizes sustainability too: 75% of its power comes from renewables, and many sites are fully wind/solar powered.

Equinix (EQIX 0.00%↑) is another major REIT. It owns 273 data centers in 77 markets globally. Equinix rents space mostly to cloud and network companies (its “major tenants” include Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Oracle, etc.). Equinix is also planning big expansions: it says it will add +24,000 cabinets by 2027 to its existing +144,000, and it expects to spend $4–5 billion per year through 2029 on new growth (up from $3.3B in 2025). That’s equivalent to a small country’s entire data center industry. Equinix says AI demand is pushing these numbers.

CyrusOne (taken private in 2022) operates around 46 data centers in 17 global markets. It’s building aggressively: a notable project is a $4 billion, 190 MW hyperscale campus in Texas. CyrusOne also says it’s shifting to a “manufacturing-led” approach to build data centers faster for AI workloads. It partners with cloud customers for built-to-suit AI centers.

QTS (private) owns or is building 75 data centers across the U.S. and Europe. It was bought by Blackstone in 2021. QTS is focusing on big new builds in key markets (Texas, Virginia, the Netherlands) and even secured a $3.5B construction loan to refinance 10 centers. Its clients range from hyperscale tech firms to governments and enterprises. QTS is betting on “hyperscale solutions” and claims to do all new greenfield centers with water-free cooling and high efficiency.

(Other names: Iron Mountain, STACK Infrastructure, Vantage Data Centers, etc., are also big developers. For example, Denver-based STACK Infrastructure has 130 data centers (77 underway) and recently got $4B financing for a 1 GW campus in Virginia.)

How big are they? According to S&P Global, in late 2024 Equinix was the 4th largest U.S. provider (4.9% market share) while Digital Realty led with 21%. These firms together control a huge portfolio of space. Equinix alone connects +10,000 businesses across its campuses. And these operators are rushing to expand capacity for AI. For instance, one report notes “Equinix and Digital Realty have a combined developable pipeline of close to 8 GW deliverable over the next 2-3 years”.

Engineering and Site Contractors

Behind every data center building is a team of construction and engineering firms. These specialty contractors have become unexpected beneficiaries of the data center boom.

Besides STRL, you have other electrical and mechanical contractors that are also reporting surge in data center work:

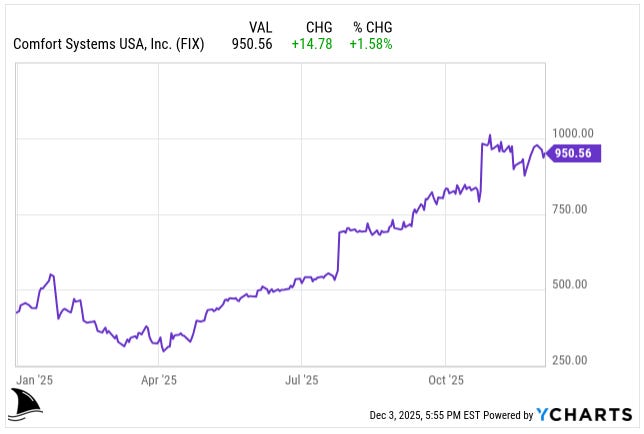

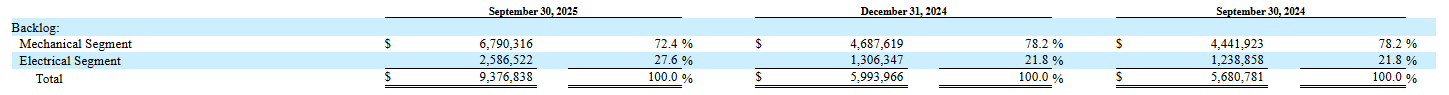

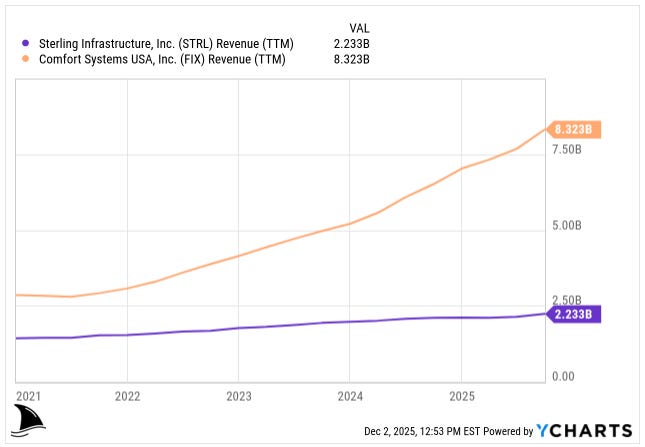

Comfort Systems USA FIX 0.00%↑

FIX (contractor for HVAC and electrical) has said data center and semiconductor projects are driving huge demand. Its stock more than doubled in 2025…

… as backlog grew from $5.7B in September 2024 to $9.4B in September 2025.

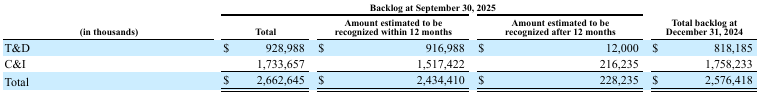

MYR Group (MYRG 0.00%↑)

MYRG (electrical contractor) noted in its Q2 2025 report that AI is “supercharging data center growth”, with +170 hyperscale and colo projects (+45 GW) on the books. Its backlog is $2.6B.

Dycom (DY 0.00%↑) and Primoris (PRIM 0.00%↑)

DY and PRIM (also specialty contractors) have similar stories: industry analysts highlight that their increased backlog is coming from data center and telecom projects.

Bottlenecks: Power, Permits, and People

Even with all this investment, building so many data centers is not easy. Several bottlenecks are slowing things down.

Bottleneck #1. Power Availability and Grid Capacity

AI data centers eat power. Lots of it. They also need water for cooling. In hot spots like Northern Virginia or the broader PJM market, utilities are running to keep up.

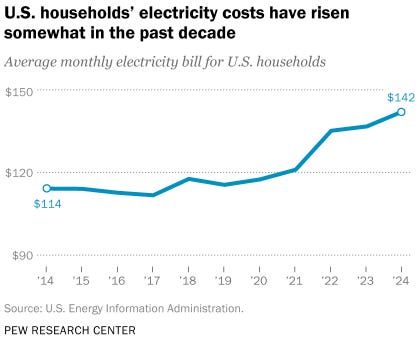

You can already see the strain in household bills. Pew’s chart on U.S. electricity costs shows the average monthly bill rising from $114 in 2014 to $142 in 2024.

That is roughly a 25% increase in a decade, and that is before the full AI wave hits. The chart does not blame data centers alone, but they are one more big straw on the grid’s back.

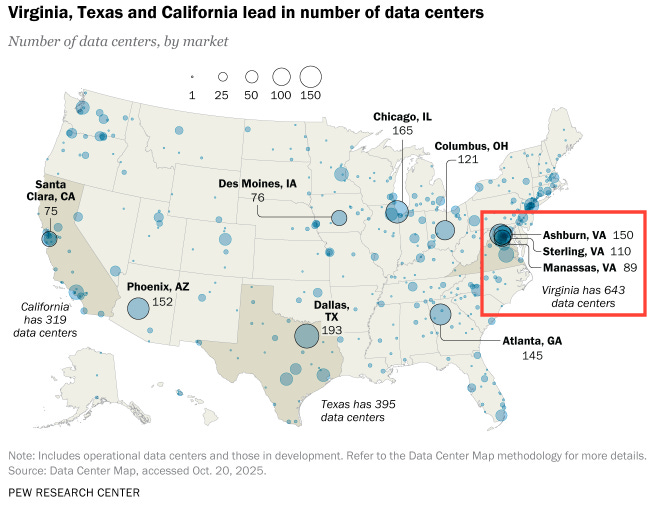

The following map explains why regulators focus so much on Virginia, Texas, and California. Virginia now hosts around 643 data centers, with clusters around Ashburn, Sterling, and Manassas. Texas has about 395, with Dallas as a major hub. California has roughly 319, anchored by Santa Clara and other Bay Area markets. Phoenix, Chicago, Columbus, and Atlanta also show up as dense clusters. These are the places where rising power demand and local politics collide most directly.

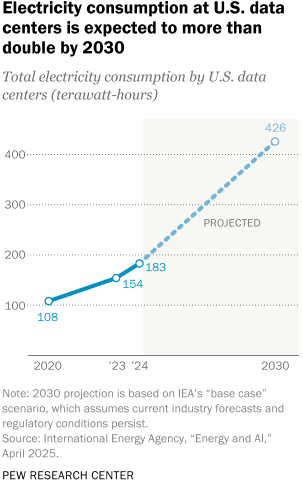

On the supply side, the numbers are eye opening. U.S. data center electricity use shows consumption rising from 108 terawatt-hours in 2020 to 183 TWh in 2024, with a base-case projection of 426 TWh by 2030.

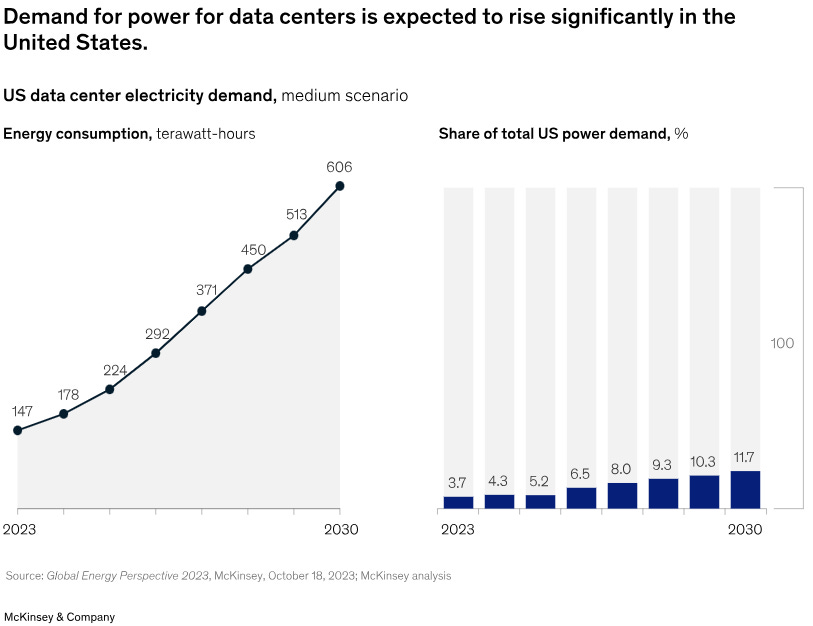

McKinsey’s own medium scenario is even more aggressive. It sees U.S. data centers using 606 TWh by 2030, up from 147 TWh in 2023, and taking their share of total U.S. power demand from 3.7% to 11.7% over that period. That is not a rounding error. That is a new industrial load class.

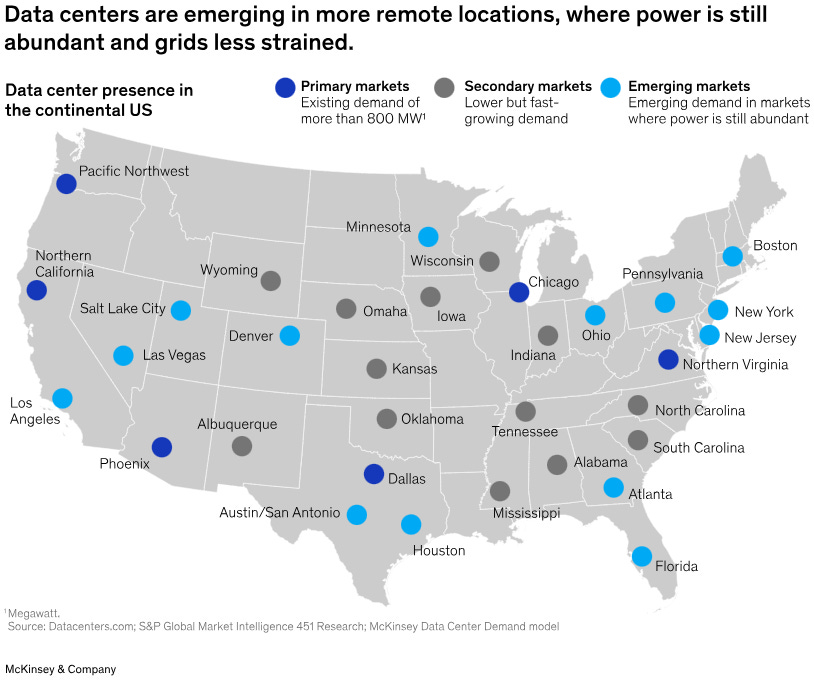

Because of this, operators are spreading out. McKinsey’s map of U.S. markets shows primary hubs like Northern Virginia, Dallas, Phoenix, and the Pacific Northwest, but also a long list of emerging locations where the grid still has breathing room. Think Wisconsin, Ohio, Alabama, Florida, and parts of the Midwest.

In plainer language, the easy sites near big cities are full. Developers are now chasing power and substation capacity wherever they can still find it.

Virginia is the clearest case study. The data center buildout has pushed Dominion Energy to plan new high-voltage substations and long transmission lines just to keep serving growth. In some local forecasts, data centers are on track to consume roughly a quarter of the state’s electricity within a few years. Regulators openly worry about reliability and rate spikes.

The same pattern shows up across PJM and other regions. In the PJM market, rising data center load has already driven billions of dollars in extra capacity costs for 2025–26, which works out to roughly an extra mid-teens dollars per month on some household bills. Utilities sit in the middle. Legislators and voters want stable prices. Hyperscalers want gigawatts of new power. That tension is why you hear more talk about forcing data centers to build or finance their own dedicated generation.

The takeaway is simple. Reliable power is the main artery for new data centers, and it is getting clogged. Unless grids expand fast, power will be the binding constraint on how quickly this buildout can continue. This is a key reason I also own POWL 0.00%↑ (read the thesis here) and AGX 0.00%↑ (read the thesis here). They are the 3rd and 4th best performers in the portfolio.

Bottleneck #2. Permitting and Siting Delays

Finding suitable sites and getting permits is another hurdle. Hyperscale data centers need huge, power-ready tracts of land near transmission. Local officials have been overwhelmed with proposals.

For instance, over 50,000 acres are approved or in the pipeline in parts of Texas and Florida. But zoning approvals, environmental reviews, and community pushback are slowing projects. Even industry groups have asked regulators to fast-track permitting, sometimes offering to finance grid upgrades in exchange.

In PJM states, a proposal was floated to “temporarily halt new data-center hookups” until the grid can serve them reliably. Data centers routinely face 1–2 year planning and permit processes.

Bottleneck #3. Land Availability

It’s surprisingly hard to find big contiguous parcels. You can imagine a DC campus like a small town as you often need +100 acres for a cluster of buildings. As core areas (Virginia, Bay Area, Silicon Prairie) fill up, developers are looking to new sites in Ohio, Michigan, Georgia, and even overseas. But any patch of open land usually needs extensive infrastructure work (roads, sewers, fiber). So land can be a bottleneck.

Bottleneck #4. Skilled Labor Shortage

Building a data center requires armies of specialized workers: electricians, pipefitters, steel workers, and engineers. A typical large DC (250,000 sq ft) can add up to 1,500 workers on-site during construction. That crew includes hundreds of high-skilled tradespeople (many unionized) earning six-figure salaries.

In other words, a single big DC is like launching a multi-million–man-hour project. And there simply aren’t enough data center–experienced crews nationwide. Contractors say they’re hiring aggressively, but projects can be delayed by labor availability. The same data center could only employ 50 permanent staff after opening, but getting there through that massive construction phase taxes the market for electricians, technicians, and project managers.

Innovations in Cooling, Security, and Sustainability

The data center boom has also sparked new ideas in how centers are built and run. Since we’re effectively stacking racks of powerful computers (which generate extreme heat), traditional air-cooling is reaching its limits.

Cooling Technologies: Liquid cooling is a game-changer. Instead of blowing cold air (inefficient for dense racks), water or refrigerant loops remove heat directly. Liquid cooling can improve energy efficiency up to 45% better than air alone. Some cutting-edge facilities even use fully immersive cooling (servers bathed in dielectric fluid) or direct-to-chip coolant. These methods greatly reduce the extra cooling power (and water for cooling towers) needed for AI centers. Also, modular cooling units that pack into the building let operators tune cooling capacity precisely. By the way, I think Canada has a great opportunity to build data centers in the artic…some food for thought Mr. Carney.

Security Innovations: Physical security in these mega-facilities goes high-tech. Modern data centers layer fences, cameras, and guards, but also use AI and biometrics. For instance, many centers now have AI-powered security models. Facial recognition, fingerprint and iris scanners, and smart video analytics can spot intruders in real time. Drones are even being tested for perimeter patrols. The idea is that as facilities grow (imagine 50-foot fences surrounding dozens of acres), you need automated systems to watch the perimeter 24/7. So builders are integrating extensive sensor networks, biometric turnstiles, and centralized AI security monitoring.

Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: Data centers consume a lot of resources, so operators are innovating to green their footprint. Many new centers are being built to high efficiency standards (Energy Star, LEED, etc.) Big companies are signing deals to match their load with solar and wind farms. Others are recovering waste heat: some DC campuses capture excess heat to warm nearby buildings. Water use is being reduced by air economizers (cooling using outside air when cold) and by using recycled/grey water for cooling towers. New refrigerants (low-GWP) and even small modular nuclear reactors have been discussed to supply clean power on-site. In southern Europe, Meta is experimenting with greenhouses using DC waste heat to grow vegetables. The pressure from regulators and communities (see below) is pushing designers to make centers as “green” as possible.

Risks and Uncertainties

Even as data center building races ahead, there are clear risks that this boom could stumble or slow:

Risk #1. Overbuilding

The biggest worry is that we might build faster than demand materializes (I wrote about this fear recently here). Hyperscalers have a history of leasing more space than they immediately need (like Amazon did with warehouses).

Recently, there are hints of overreach. For instance, when DeepSeek’s new AI model trained much cheaper than expected, it rattled markets. Microsoft’s CEO even warned publicly that the industry “was headed toward an overbuild”.

Reports emerged of Microsoft walking away from some pre-leases and projects when demand projections changed. Overinvesting in data center infrastructure risks stranding assets. If AI hype cools or efficiency improves, some of these future data centers might turn into empty warehouses. Even capex forecasts could be revised if the tech landscape shifts.

Risk #2. Permitting and Policy Headwinds

The intense data center growth has attracted scrutiny. Communities and regulators have begun pushing back. Some states (California, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, Virginia) are considering laws to force data centers to use more renewable power and report exactly how much energy and water they use.

In places like Virginia or Oregon, voters have even passed moratoriums or tighter rules on data centers to protect residents from higher electricity bills. Legislators fret that household rates could spike (and studies suggest U.S. bills could rise 8% by 2030 due to data centers, with Virginia up 25% in hot spots). If enough states clamp down or require expensive retrofits, future projects could face new hurdles or costs.

Risk #3. Economic and Market Shifts

Tech spending can be cyclical. If the economy slows, or if AI hype proves weaker or more efficient than expected, corporate capex may shrink. Already, companies are re-prioritizing: reports indicate that hyperscalers may spend less on data centers than initially planned, or shift focus to existing campuses.

For example, if an AI breakthrough drastically cuts compute needs (as DeepSeek hinted it might), companies might cancel some buildouts. It’s possible that some of the planned $1.8T US hyperscaler spending through 2030 is pulled back if bottom-line pressures mount.

Risk #4. Energy and Environmental Pushback

Data centers are under environmental microscope. Critics worry they are “data center farms” sucking up local resources. There are growing calls to slow growth if it strains grids or pollution.

For instance, in regions like North Virginia or California, legislators and activists are demanding that data centers take responsibility for the strain they cause. If public sentiment turns hostile, approvals could become harder, or new taxes could be applied to high-energy users.

Risk #5. Skills and Supply Chain

The same labor and equipment shortages that challenge the buildout could also threaten it. If contractors can’t find enough crews or chips (like GPUs) remain on long lead times, projects stall. We already see reports that GPU supply could lag demand, and shipping or parts backlogs can delay builds.

STRL’s Three Advantages

In a field as competitive as construction, a sustainable competitive advantage is what separates a good company from a great investment. Sterling’s edge has evolved beyond simply winning bids. It has become a strategic partner for the world’s most demanding technology clients, for whom speed, reliability, and execution are paramount.

Edge #1. Execution and Scale

Time is money, especially in the tech world. For a hyperscaler, a six-month delay on a new data center can mean billions in lost opportunity. STRL has built a reputation for managing massive, complex, and mission-critical site development projects on schedule. This proven ability to execute is perhaps its most valuable asset and a key reason it wins repeat business.

Edge #2. Integrated Service Offering

The acquisition of CEC was a masterstroke. By combining large-scale site development with critical electrical services, STRL can now offer a more integrated, turnkey solution. This streamlines the construction process, reduces coordination friction, and ultimately accelerates project timelines. This integrated model is already creating a significant competitive advantage.

Edge #3. Blue-Chip Customer Relationships

Sterling works directly for the giants of e-commerce and cloud computing. These are not one-off projects; they are deep, multi-year relationships. This privileged position gives STRL incredible visibility into future capital spending plans and often allows the company to get involved in the planning stages of new projects long before they go out to bid. This concentration with a few large customers is a potential risk, but I see it more as a feature. These deep partnerships with the world’s most important technology companies mitigate risk by providing significant future visibility.

While the construction industry is fragmented, STRL has few direct public peers that do exactly what it does. However, while these firms operate in similar or adjacent sectors, STRL’s specific focus on large-scale site development for high-tech facilities, now powerfully combined with mission-critical electrical services, carves out a specialized and highly lucrative niche.

Peers: Who Earns Their Multiple and Why

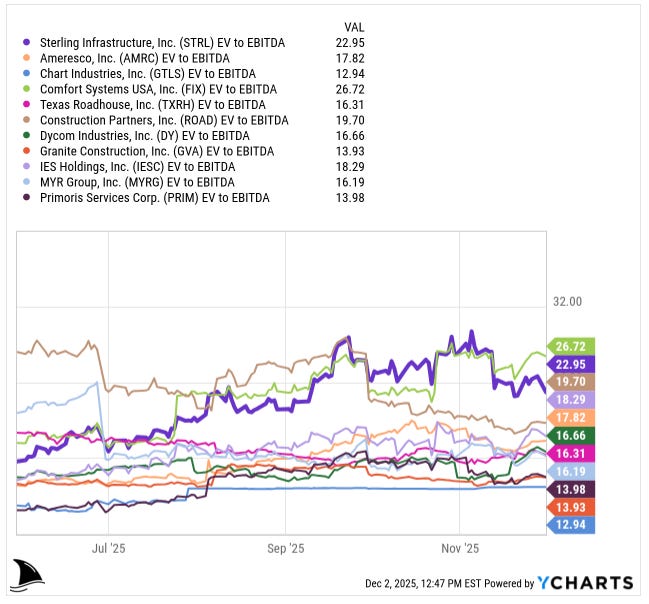

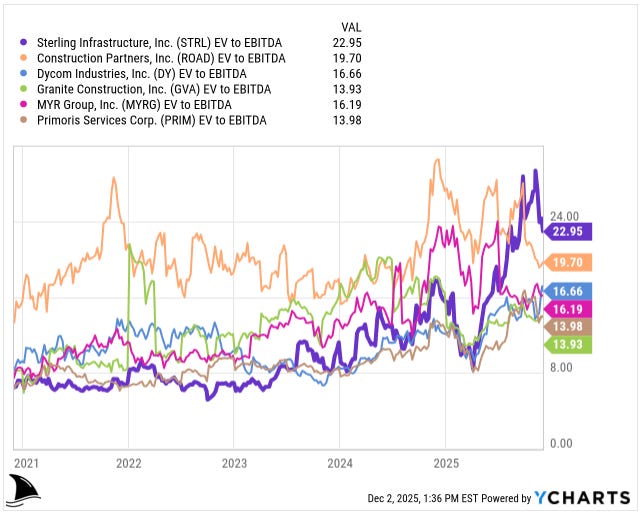

While STRL trades near the high end of the peer group on EV/EBITDA…

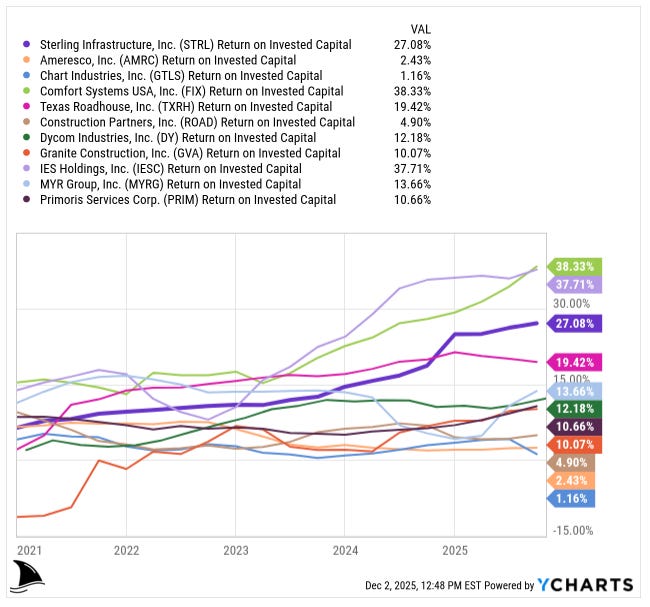

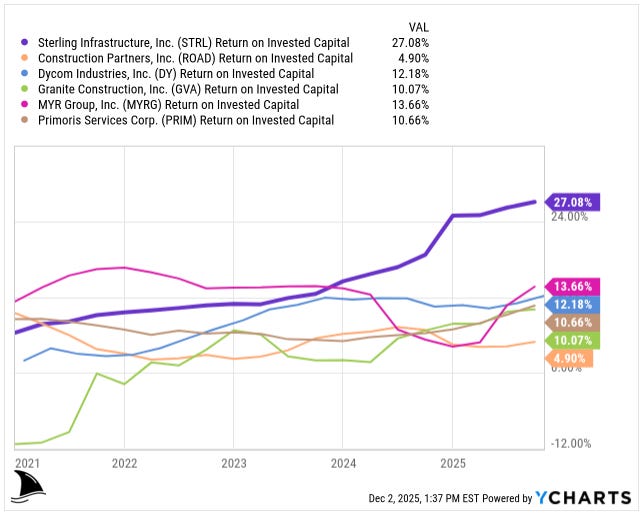

… it also sits near the top on ROIC.

Only two names earn higher ROICs: FIX 0.00%↑ and IESC 0.00%↑. Everyone else trails by a wide margin.

That is important. A high multiple with a low ROIC is usually a red flag. A high multiple with a high ROIC tells a different story. STRL lives in that second camp. It is a high quality, high return contractor that the market has already discovered.

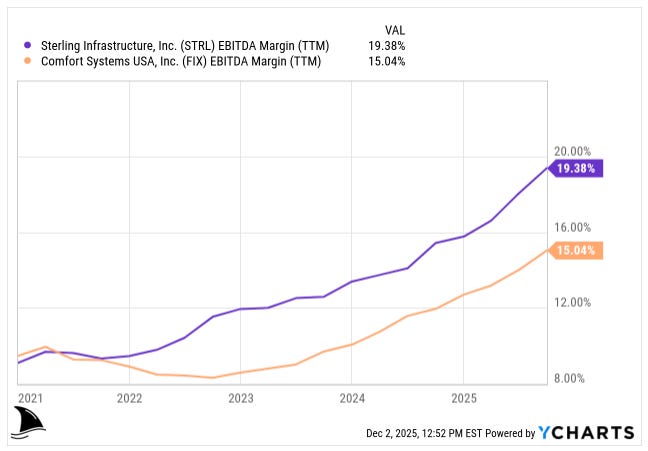

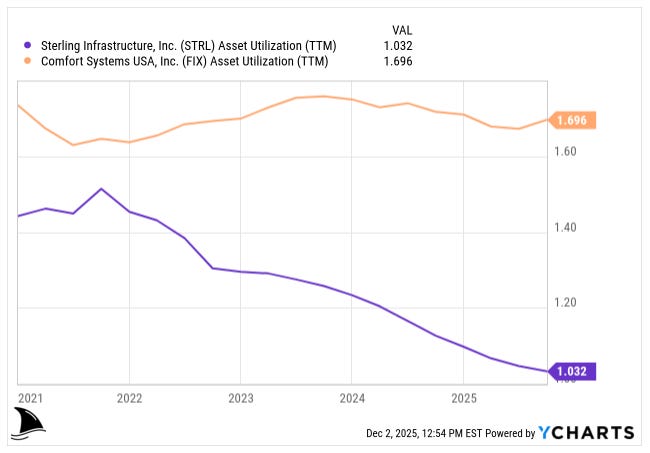

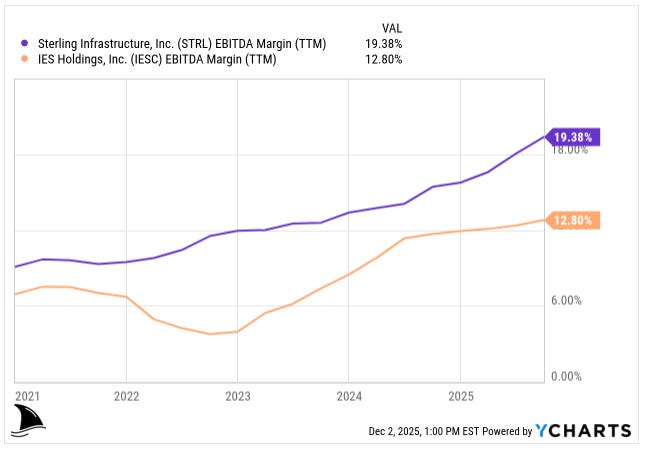

FIX as the “aspiration” case

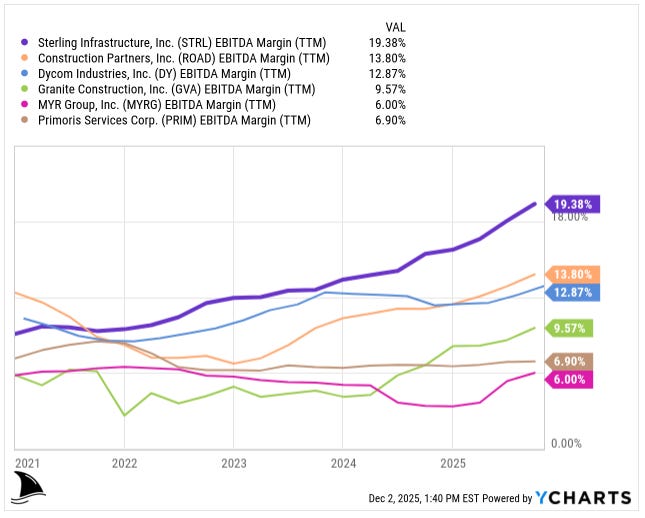

FIX is the clear profit leader in this group. Its ROIC is at the top of the chart, near 38%, while STRL sits around 27%. Yet FIX’s EBITDA margin is actually lower than STRL’s.

So how does FIX earn a higher ROIC with a lower margin? Scale and capital intensity. FIX is almost four times STRL’s size in revenue.

It runs a very asset light model. Most of its work is mechanical and HVAC installation and service. That uses more people and subcontractors, and less heavy equipment and owned real estate. The company turns its capital faster, because it does not need big fleets of yellow iron or large stockpiles of materials on its own balance sheet.

Remember the basic ROIC formula:

ROIC ≈ operating profit / invested capital

If you need a primer on ROIC, I wrote one:

You can raise ROIC either by increasing the numerator (more profit per dollar of sales) or by shrinking the denominator (less capital tied up per dollar of sales). FIX does both. It runs at good, not spectacular, margins, but it keeps its capital base very lean. Negative working capital from customer deposits, limited PP&E, and high project turnover all help. That is how you get a 30s ROIC even with mid-teens margins.

In my view, FIX is a useful “aspiration” for STRL. If Sterling continues to grow its top line in data centers and other E-Infrastructure, and if it trims the capital it needs per dollar of revenue (not sure how much is possible, but it is a good challenge), its ROIC can drift closer to FIX’s level over time. The fact that FIX trades at an even higher EV/EBITDA multiple, around 27x, shows what the market is willing to pay for that combination of scale and returns.

Why IESC’s ROIC tops STRL’s

IES Holdings is the other stand-out. It also shows ROIC in the high 30s, slightly below FIX but above STRL. Yet again, its EBITDA margin sits below STRL’s.

The story is similar. IESC is an electrical contractor and integrator with a mix of high-value services: data centers, industrial electrical work, and communications. It does not pour massive amounts of concrete or own big fleets of earthmoving equipment. It earns good project margins and turns its balance sheet quickly.

IESC’s invested capital per dollar of profit is simply lower than STRL’s. It needs less plant, less equipment, and often works with shorter project cycles. That means less cash tied up in long-duration jobs, retainage, and heavy machinery. In ROIC terms, the denominator stays small.

So even with a thinner EBITDA margin, IESC’s capital-light model gives it a higher ROIC. The market gives IESC a healthy multiple of 18x EV/EBITDA, which is a discount to STRL’s 23x despite the stronger ROIC. That gap likely reflects its smaller scale and lumpier end markets. For me, it reinforces the idea that STRL’s premium multiple is not crazy, but also that there is room to improve its capital efficiency.

STRL’s place in the pack

Now zoom out and look at the whole group.

If I focus on the core civil and infrastructure peers (GVA 0.00%↑, PRIM 0.00%↑, ROAD 0.00%↑, MYRG 0.00%↑, and DY 0.00%↑) the picture is clear. Most of them sit in the mid-teens EV/EBITDA range…

…with ROIC in the single digits or low teens. They do similar heavy work but earn much lower returns on their capital.

None post better EBITDA margins than STRL.

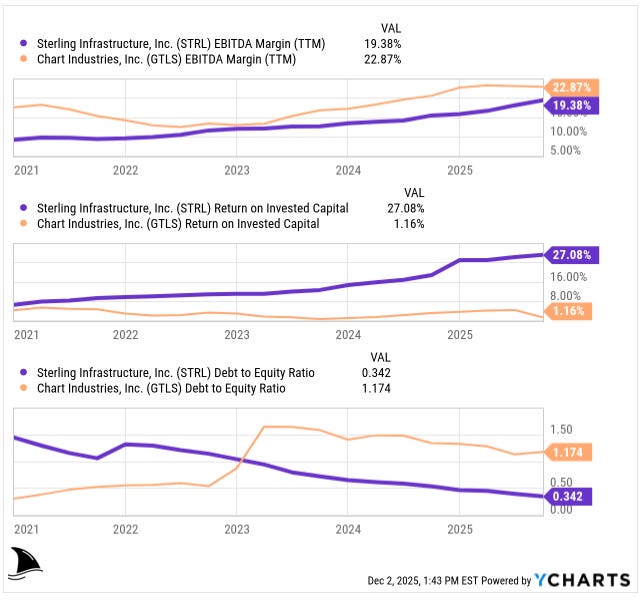

GTLS 0.00%↑ is the clean example of good margins but lousy capital management. It has the best EBITDA margin in the group, around 23%, yet ROIC is barely above 1% because it carries a big balance sheet and a lot of debt.

As you can see, STRL sits in a sweet spot between these groups. Its EBITDA margin is near the top of the pack. Its ROIC is third-best overall, behind only FIX and IESC and well ahead of the core civil peers. Its EV/EBITDA multiple is at the higher end, around 23x, but not the highest. FIX trades richer and ROAD is in the same neighborhood, while several lower quality contractors still sit in the mid-teens.

So yes, STRL now trades at the upper end of the peer EV/EBITDA range. When I pair that multiple with its strong margins and top tier ROIC, especially versus the true civil comps, the premium looks earned. FIX and IESC sit above it as quality benchmarks rather than direct comps, and I see them more as a roadmap for what STRL’s returns can look like as the business scales.

Management Quality & Capital Allocation

Joe Cutillo joined Sterling in 2015 when the company was close to the wall after years of losses and executive turnover. He became CEO in 2017 and led a full rebuild of the business. Since then:

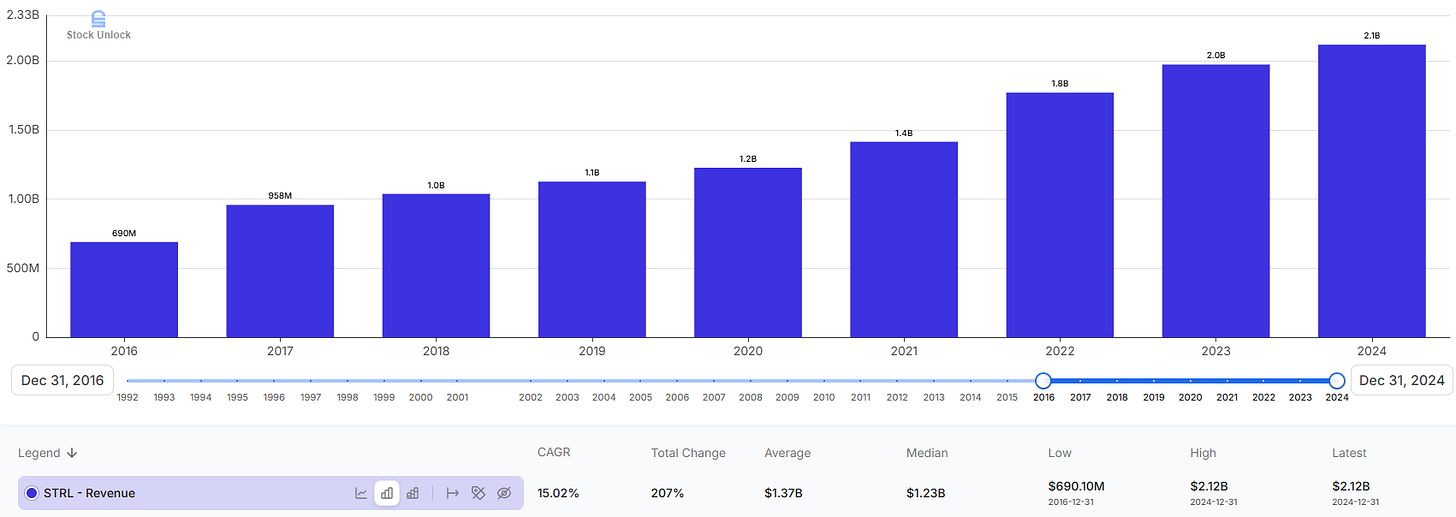

revenue has grown to more than 2 billion dollars…

…gross margins moved from less than 6% to more than 20%…

…and the share price increased from $8 to $330 over the period.

That improvement did not come from a hot project or a lucky cycle. It came from a clear strategy and disciplined capital allocation.

Cutillo Sterling away from low bid, heavy highway work and into higher margin, lower risk infrastructure services. In 2016, traditional heavy highway represented the bulk of the company. Today, E-Infrastructure and Building Solutions drive most of operating profit, with E-Infrastructure alone contributing more than half of adjusted revenue and nearly three quarters of segment operating income.

Management used M&A as a lever, but not as a crutch. Plateau, Petillo and other deals built out a top tier site-development platform focused on large, complex jobs like data centers and advanced manufacturing plants. More recently, the team added Drake to deepen its footprint in Dallas housing and commercial work, paying $25 million plus an earn-out for a business that fits neatly inside Building Solutions.

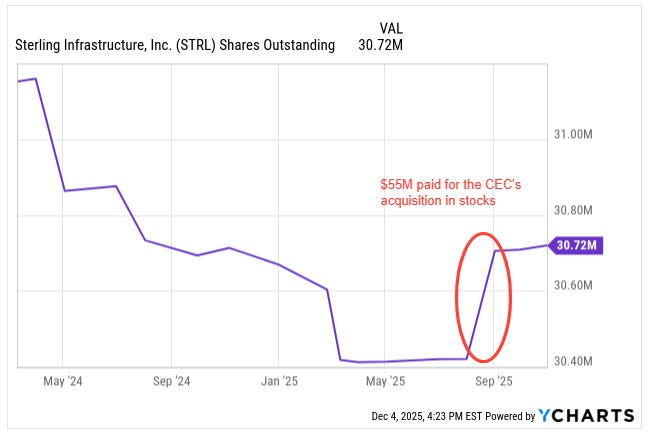

The CEC Facilities Group acquisition is the latest and most important move. Sterling agreed to pay $505 million up front, split between $450 million in cash and $55 million in stock, plus up to $80 million in earn-outs tied to operating income through 2029. CEC brings mission-critical electrical and mechanical contracting, with more than 80% of revenue from semiconductor, data center, and manufacturing customers.

Management expects CEC to generate $390 to $415 million of revenue and $51 to $54 million of EBITDA in 2025, roughly a 13% margin, and to add $0.63 to $0.70 of adjusted EPS in that first year.

On my read, that is classic Sterling capital allocation. They are paying about 9x to 10x forward EBITDA for a high growth, high return platform in the exact markets they already know well. CEC lets Sterling move from “dirt and concrete” at the start of the project into the electrical guts of the building and then into ongoing service. That means more wallet share per project and better use of the customer relationships they have already built.

The other side of capital allocation is what they choose not to own. The sale of the Myers aggregate business and the decision to restructure Road and Highway Builders into an equity method investment both reduced exposure to low return, capital heavy operations and sharpened the focus on higher margin work.

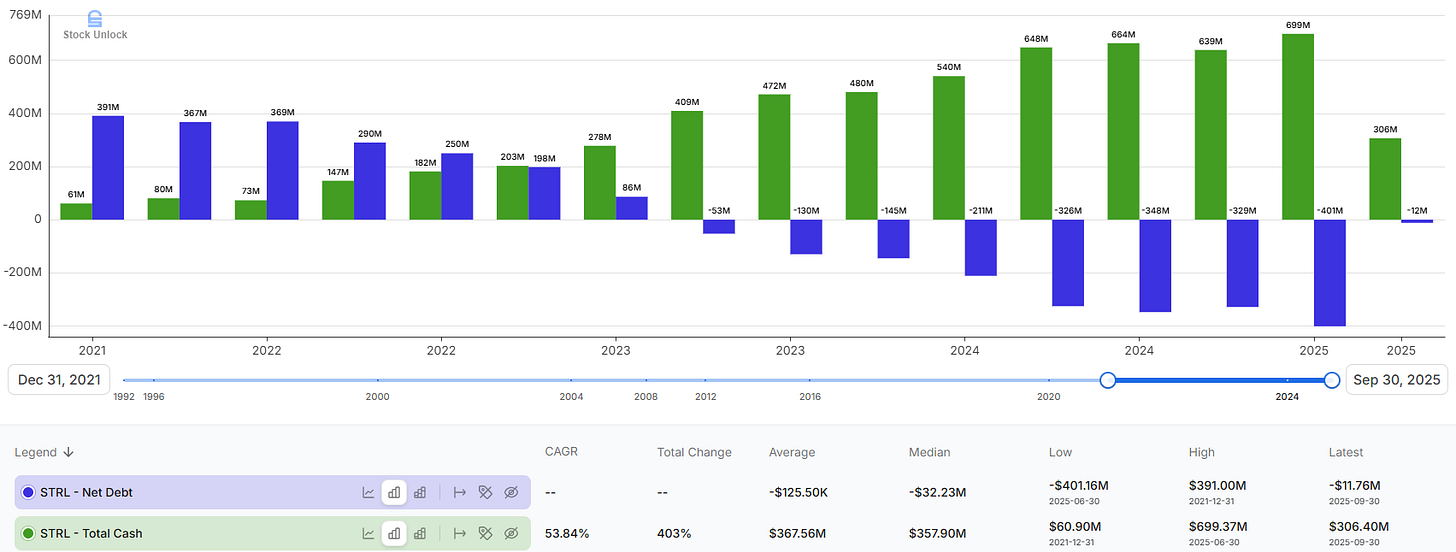

You can also see the discipline in the balance sheet. Despite this string of acquisitions and strong growth, Sterling has kept leverage low. By September, 2025, the company held over $300 million of cash and sat in a small net cash position.

Management used that cash plus ongoing free cash flow to fund deals and buy back stock, rather than stretch the balance sheet with aggressive debt.

That gives the team room to keep playing offense if good assets come to market, or to defend the downside if the cycle turns.

Share repurchases sit next in the hierarchy. In late 2023 the board authorized up to 200 million dollars of buybacks through the end of 2025. By the first nine months of 2025, Sterling had repurchased about 357 thousand shares for $48.5 million. Management is not trying to time the stock to the penny. They are using repurchases as a flexible tool when the shares trade below their view of intrinsic value and when M&A opportunities are scarce.

There is no dividend. With projects and acquisitions that can reasonably earn mid-teens to high-teens ROIC, I want them to reinvest rather than send me a small cash yield. The board seems to agree. The capital allocation ladder is clear: fund organic growth, pursue selective M&A that raises the company’s long-term ROIC, maintain a strong balance sheet, then buy back stock.

Incentives line up with that plan. Management compensation tilts toward performance metrics like earnings growth, EBITDA and stock price performance, and the proxy highlights “The Sterling Way” as the cultural framework that emphasizes safety, project execution, and returns on capital. Cutillo’s own story as a turnaround specialist also matters here. He earned his reputation by fixing broken construction businesses, not by levering them up.

When I step back, I see a leadership team that has done three hard things at once. They changed the mix of the business toward higher quality work. They deployed capital into aligned acquisitions at reasonable prices. They kept the balance sheet clean while still returning cash through buybacks. That is exactly the mix I want behind a company that now sits at the center of a long data center and manufacturing buildout.

Financials & Valuation: Paying for Growth

Sterling is not a “story stock”. The numbers already moved.

In 2024, revenue reached about $2.1 billion with gross margin at 20% and solid double-digit operating margins. Through the first nine months of 2025, revenue grew to $1.73 billion, up from $1.62 billion a year earlier, with gross margin improving to 23.5%.

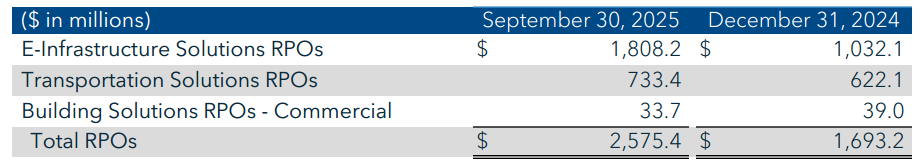

Backlog and awards show where this is going. At the end of Q3 2025, reported backlog stood at $2.58 billion, with another $868.8 million in unsigned awards.

Combined backlog was $3.44 billion, roughly 2.1x YTD revenue. Most of that sits in E-Infrastructure. Management highlighted that E-Infrastructure backlog grew 97% y/y and that the opportunity set, including unsigned work, already exceeds $4 billion.

On top of that, the balance sheet now carries roughly $12 million of net cash, with $306 million of cash and about $295 million of debt, plus an undrawn $150 million revolver. So I am not paying for a stretched balance sheet. I am paying for growth.

My fair value comes from a DCF model. In my base case, that DCF points to a target price of $455 per share, which is about 36% above current levels. The model is not magic. It rests on a set of operating assumptions that tie back to what Sterling already does, what management is guiding to, and how I see the data center and infrastructure cycles playing out.

Let me walk through the key levers.

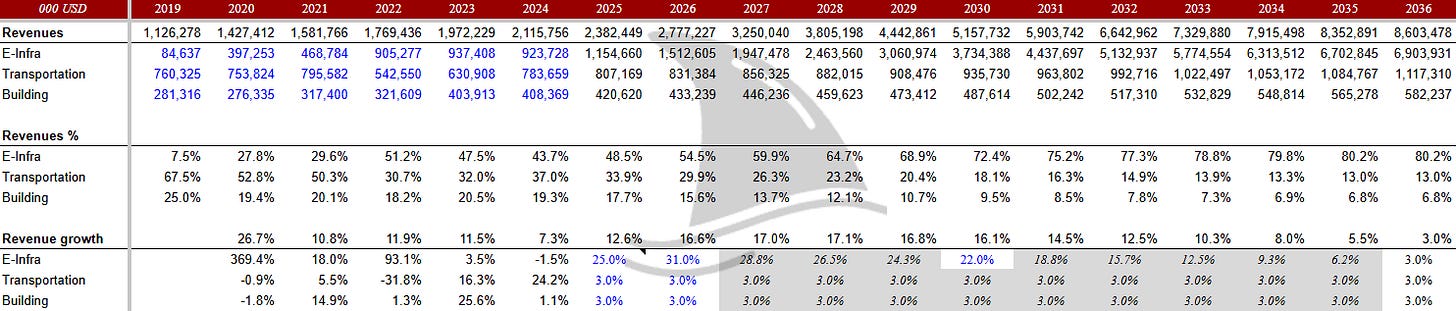

Revenue by Segment: E-Infrastructure Drives The Bus

I anchor the model on 2024 revenue of $2.116 billion. Management’s Q3 2025 guidance calls for 2025 revenue of $2.375 to $2.390 billion, which implies roughly 12% growth for the year.

From there, I split the forecast by segment. Total revenue grows from $2.38 billion in 2025 to about $5.16 billion in 2030.

The basic shape is:

High growth in the next five years, driven by AI data centers and related E-Infrastructure work.

Gradual normalization after 2030, when data center growth slows and the mix tilts back toward more “steady” transportation and building work.

E-Infrastructure Solutions

This is the heart of the thesis. Management now expects E-Infrastructure revenue growth of 30% or more on an organic basis in 2025 and close to 50% including the CEC acquisition, with full-year adjusted operating margins around 25%.

In my model, E-Infrastructure revenue grows from about $1.15 billion in 2025 to roughly $3.7 billion in 2030. EBITDA margin for this segment climbs from about 26% in 2024 to just over 32% by 2030.

I assume very strong growth for the next five years as hyperscalers and REITs add new AI and high-density facilities. I let growth slow in the back half of the forecast as the market matures and Sterling’s base gets larger, but I keep E-Infrastructure as the main engine of the company.

By 2030, E-Infrastructure accounts for almost 3/4 of total revenue and 94% of EBITDA. That mix shift is what powers the margin story.

Transportation Solutions.

Transportation is the steady middle child. It benefits from the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and from state and local spending, but it does not have the same structural tailwind as AI data centers. Management guides to low-teens revenue growth in 2025 and adjusted operating margins of 13.5% to 14%, up from 9.6% in 2024.

In the model, I assume:

Low single-digit (3%) as federal dollars keep flowing and Sterling works through a growing backlog.

EBITDA margins of 10%, lower than the guidance.

Building Solutions.

Building is the cyclical laggard. Housing remains soft, and management has been clear that they do not expect a near-term rebound.

In the model, I assume:

a constant 3% revenue growth.

EBITDA margins sit in the low teens.

Building is not the driver of upside. It is there to provide some diversification and to soak up corporate overhead.

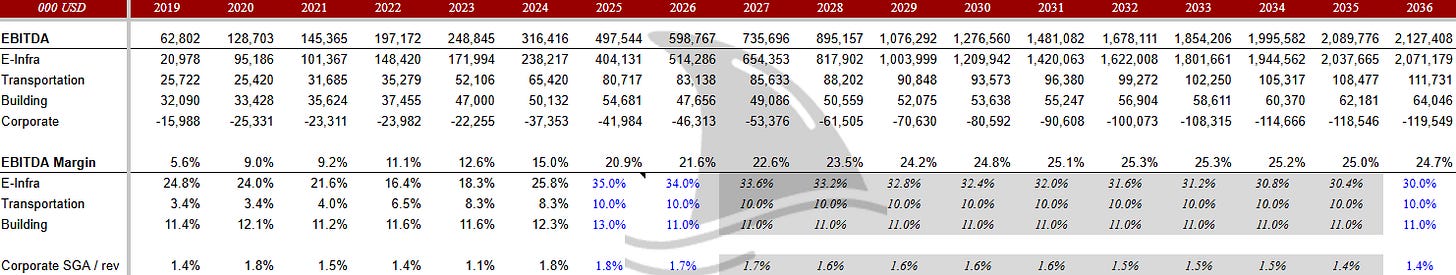

Margin Structure: Mix Shift And Operating Leverage

Gross margin rising from about 20% in 2024 to the high-20% range.

Through Q3 2025, Sterling’s gross margin was 23.5%, and Q3 alone came in at 24.7%.

I also assume G&A runs around 6% of revenue in the near term, roughly in line with 2025 guidance, and edges down slightly over time as the company scales.

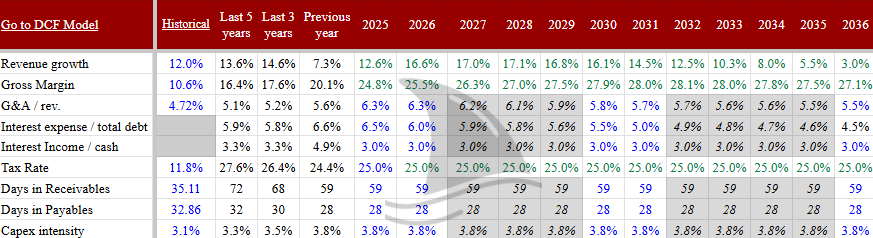

Cash Flow, Capex, And Working Capital

Sterling converts a large share of earnings into free cash flow. For the first nine months of 2025, the company generated $253.9 million of operating cash flow on $202.6 million of net income.

In the model:

I assume capex runs at 3.8% of revenue. That lines up with recent history, where capex has sat in the mid single digits of sales as Sterling invests in equipment and yards but remains less asset heavy than many peers.

I keep depreciation a bit below capex in the early years, then allow it to converge as the asset base matures.

For working capital, I assume roughly two months of sales tied up in receivables and about one month offset by payables. That is consistent with what you would expect in large fixed-price and unit-price jobs with milestone billing.

Taxes, Capital Structure, And Discount Rate

On taxes, I use a 25% effective rate from 2026 onward. That is almost exactly what management guides to, and it sits near the combined federal and state rate for a U.S. contractor.

On capital structure, I hold net leverage around or below 1.5x EBITDA in the base case. Management has said they are comfortable with a forward debt to EBITDA ratio of about 2.5x but currently sit well below that level.

I do not assume a big increase in leverage from here. Instead, I assume that excess cash goes mainly to tuck-in acquisitions and buybacks.

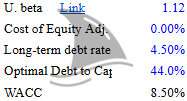

For the discount rate, I apply a 8.5% cost of capital. That feels reasonable for a mid-cap contractor with above-average growth, moderate cyclicality, and a clean balance sheet. That is based on an unlevered beta corrected for cash of 1.12 for the construction sector as per Damodaran.

For the terminal value, I use:

A 3% long-run growth rate, in line with nominal GDP and the Main Assumptions trajectory as growth fades toward the low single digits.

When I roll those cash flows forward, adjust for net cash of about $12 million, and divide by roughly 31 million diluted shares, the result is a DCF fair value of about $455 per share.

Top Three Risks to the Thesis

Risk #1. Concentration and Cyclicality

The company’s success is becoming increasingly tied to the E-Infrastructure segment. In 2022, for example, just four customers accounted for 35% of that segment’s revenue. A downturn in capital spending by these key hyperscaler clients could significantly impact STRL’s results. The cyclical nature of the Building Solutions segment also remains a secondary headwind.

Risk #2. Project Execution Risk

Sterling’s reputation is built on its ability to deliver large, complex projects on time and on budget. This type of work carries inherent risks of cost overruns, labor shortages, supply chain disruptions, and contractual disputes. A single major project failure could harm both its profitability and its hard-won reputation with key clients.

Risk #3. Macroeconomic Headwinds

Persistent inflation continues to put pressure on the cost of materials and labor. While Sterling has managed these pressures well, a significant spike could erode margins. Furthermore, broader interest rate policy and economic softness could continue to dampen the Building Solutions segment and create uncertainty for customers across all segments.

Verdict

STRL’s journey from a low-margin highway contractor to a premier growth story is a testament to its visionary management and flawless execution. The company is no longer just a construction firm; it is a critical enabler of the AI revolution, providing the essential groundwork for the digital age.

Despite a valuation that is admittedly rich, I believe the market is still underestimating the durability and scale of the data center construction boom. STRL’s strategic position as a preferred partner to the world’s largest technology companies, its proven ability to execute complex projects, and its newly integrated service offerings create a powerful and sustainable competitive advantage. The company’s massive and growing backlog in its highest-margin segment provides a clear path for continued, profitable growth for years to come.

Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform, and others like Meta