Weekly #44: The Rise and Fall of Moats: When Walls Built to Protect Become Traps

Portfolio is up 17.1% YTD. From Anheuser-Busch to Blockbuster, history shows that walls meant to protect often trap, and the same lesson applies to investors.

Hello fellow Sharks,

We keep grinding higher. The portfolio is now +17.1% YTD, and since inception, the portfolio has returned 2.1x the market’s performance. Not bad for a pack of Sharks hunting in waters most people don’t even notice. If you want to skip straight to the numbers, jump to the Portfolio Update.

Earlier this week, I shared my thoughts on KINS’s Q2 results. A quarter that showed how discipline and smart reinsurance moves can translate into record profits. If you missed it, the quick summary is simple: earnings up, protection stronger, and guidance raised.

This week’s Thought of the Week takes a step back. It’s about how the walls we build to protect ourselves can end up imprisoning us. I walk through how this idea shows up in history, in psychology, and in business, where even industry leaders like Kodak, Blockbuster, or Anheuser-Busch learned the hard way that fortresses eventually crumble. I also share two personal experiences that drove the lesson home for me: one during my time at ABI right after the InBev merger, and another years later at Entel in Chile. Both showed me that comfort zones can be the most dangerous places to sit in.

Enjoy the read, and have a great Sunday!

~George

Table of Contents:

In Case You Missed It

KINS Q2: Profits, protection, and a bigger plan

Kingstone (KINS 0.00%↑) just posted one of its strongest quarters in years: record EPS of $0.78, a combined ratio of 71.5%, and annualized ROE north of 50%. Premiums grew double-digits, reinsurance protection was boosted by 57% at only a modest cost, and the company even placed its first $125M catastrophe bond. Management raised full-year guidance across the board and reinstated the dividend. Clear signs that the turnaround plan is delivering. You can read my full breakdown here.

Thought of the Week: The Walls You Put Up to Protect Yourself Can Imprison You

I’ve read my share of “rise and fall” books over the years. The Rise and Fall of American Growth sits dog-eared on my shelf, and on my to-read list are The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs.

Honestly, you can find a “rise and fall” title on almost anything from the Chinese dynasties to Enron to Long-Term Capital Management. Give it a little time, and I bet we’ll get a rise and fall book about the U.S. as a superpower, Putin, and about Elon Musk. The theme is everywhere. It even shows up in proverbs: “What goes up must come down.”

I stumbled on a line that stuck with me: “The walls you put up to protect yourself can imprison you.” The more I thought about it, the more it clicked. Almost every “fall” after a great “rise” comes down to this. The powerful build walls to protect their position, and in the process, they trap themselves. They close off options, lose flexibility, and eventually get blindsided.

There are countless examples, so many that this could turn into a book of its own. But instead of writing Rise and Fall of Walls 101, I’ll stick to a couple of stories that matter for us as investors, and then dig into what we can actually do about it.

Building Walls: A Protective Instinct with a Dark Side

We humans love to feel secure. We put up walls, sometimes literally, sometimes figuratively, hoping to keep out threats. We think we’re being smart by protecting ourselves. Yet history, psychology, and everyday life show a great irony: those same walls can trap us inside.

As Jim Rohn put it:

The walls we build around us to keep sadness out also keep out the joy.

In other words, the barriers we erect for safety can become our own prison bars.

This idea shows up across philosophy and psychology. Many people, for example, avoid new relationships or challenges after being hurt. It feels safe to shut others out or to stick to what we know. It’s like building an emotional castle with high walls. You might keep out pain, but you also lock out growth and friendship.

Over time, your comfort zone shrinks into a lonesome cell. Psychologists warn about this tendency: avoiding vulnerability may shield you from some short-term hurt, but it often leads to long-term isolation. It’s the teenager who never tries out for the team to avoid rejection, only to end up missing the fun of being on one. It’s the investor who never risks a dollar outside of a savings account, only to realize years later that inflation has silently stolen the wealth they tried so hard to guard.

In trying not to lose, we can fail to win.

Philosophers have noted this paradox for ages. Ancient wisdom and modern research both suggest that openness is crucial for a meaningful life. If I lock myself in an ivory tower, I may be safe, but I’ll also be alone and untested. Growth usually happens when we venture outside our walls. A sapling grown inside a greenhouse might be shielded from wind and frost, but it will never grow into a mighty oak unless it faces the elements. Our personal walls work the same way: they keep us from the very experiences that strengthen and enrich us.

History’s Cautionary Tales: From Great Walls to Iron Curtains

History gives examples of walls intended for protection that ended up imprisoning those behind them.

One case is the Berlin Wall.

East Germany’s government built the Berlin Wall in 1961, claiming it was to protect its people and system from Western “fascists.” In reality, it was meant to stop East Germans from fleeing to freedom in the West. Overnight, the wall turned East Berlin into a giant prison yard for its citizens; about 17 million people found themselves sealed in. The Wall stood for nearly 30 years, a concrete symbol of how a barrier meant to “keep the country safe” had enslaved it instead. When it finally fell, the world rejoiced as East Germans ran free. It was a literal reminder that walls can come to define your captivity rather than your safety.

Another historic wall, the Great Wall of China, was built to guard an empire from invaders. It certainly slowed down enemies and protected regions for a time. But the Ming dynasty became so inward-focused behind that wall that they neglected other threats and innovations. In the 17th century, invaders (the Manchus) simply went around or bribed their way through. China’s leaders had poured resources into an immense wall, thinking it made them invincible, but it arguably led to a false sense of security. The empire fell anyway, and the wall remained as a heavy monument to strategic overconfidence. It’s a bit like a business today focusing all its energy on defending its existing product, while competitors find a path to outflank it. A wall can be circumvented, and if you’ve been complacent behind it, you’re in trouble.

Even without bricks and mortar, nations have walled themselves off. For over two centuries, Japan’s Tokugawa shogunate enforced sakoku, a policy of extreme isolation. The idea was to protect Japan from foreign influence and colonial threats. For a while, it did preserve stability and tradition. But by the mid-1800s, when forced to open up, Japan discovered it had fallen technologically behind the Western powers. The walls of isolation left it weak in the face of modern cannons and steamships. Japan had to scramble to catch up during the Meiji Restoration. The lesson? Staying behind walls can mean stagnating while the world moves on. The protective cocoon becomes a stifling cage.

These examples highlight a pattern. A fortress mentality can backfire. Whether it’s a literal wall or a metaphorical one, putting too much faith in static defences often means neglecting growth and change. Eventually, reality breaks in, and those unprepared, hiding behind yesterday’s fortifications, are the ones who suffer.

The Moat That Became a Prison: Complacency in Business

Investors often talk about companies having “moats”: durable competitive advantages that protect profits. (read Moats 101: The Ultimate Guide to Competitive Advantages in Investing)

But sometimes a moat can turn into a moat with no drawbridge: the company fortifies itself so much that it can’t adapt or escape its own walls. In business history, many giants have fallen not because they lacked defences, but because they defended the wrong things for too long. They built walls around an old business model and ignored the changing landscape outside.

Let’s look at a few examples:

Kodak’s Fear of Digital

Kodak was the king of film photography for much of the 20th century. It actually invented the first digital camera in 1975. But management got scared; they worried digital images would undermine the lucrative film business. To protect their film cash cow, they essentially locked the new innovation in a vault.

One Kodak engineer recalled that leadership’s reaction to his early digital camera prototype was “that’s cute, but don’t tell anyone about it”. Kodak’s leaders built a wall around the film business, hoping to keep the digital threat at bay.

The result?

Competitors raced ahead with digital cameras, while Kodak sat idle. By the time Kodak tried to catch up, it was too late, as the market had moved on and film was nearly obsolete. Kodak went from a household name to bankruptcy by 2012. The walls they erected to protect their profitable film business ended up imprisoning them in a dying market.

Blockbuster’s Missed Opportunity

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Blockbuster Video had a dominant position in movie rentals. They had stores everywhere, a well-defended fortress of shelf space and late fees.

Along came a tiny startup, Netflix (NFLX 0.00%↑), offering DVD rentals by mail (and later, streaming). In 2000, Netflix’s founders approached Blockbuster and offered to sell Netflix for $50 million. Blockbuster’s CEO, John Antioco, literally laughed at the deal. He dismissed Netflix as a “very small niche business” and chose to protect Blockbuster’s traditional model instead.

We all know how that story ended.

Netflix became a streaming giant, and Blockbuster’s walls crumbled into dust. By trying to keep things “safe”, clinging to late fees and physical stores, Blockbuster trapped itself in a business model consumers were abandoning. The one remaining Blockbuster store (now basically a museum piece) is a testament to how dangerous corporate comfort zones can be.

The BlackBerry Saga

For a while, BlackBerry (Research In Motion) was the king of smartphones (back when they were called “PDAs”). Governments and executives loved BlackBerry’s secure email and physical keyboard. BlackBerry walled itself into serving enterprise customers and scoffed at the idea that consumers wanted full-touchscreen phones without keyboards.

Then the iPhone and Android came along, appealing to regular users with big touch displays and lots of apps. BlackBerry’s leaders initially tried to protect what they had; they doubled down on keyboard devices and security features, assuming those walls would keep their business safe. But the mass market had moved to full-screen touch devices. Developers and users flocked elsewhere.

BlackBerry’s once-impenetrable enterprise moat shrank year by year, as the company’s devices became relics. By the time BlackBerry tried touchscreens and app stores, it was far behind. Its secure messaging fortress was wonderful, but it became a gilded cage in a world where people valued a broad ecosystem over a single feature.

BlackBerry’s market share and share price collapsed…

…another victim of walls that prevented adaptation.

I could list many more:

Xerox invented the modern personal computer interface in its PARC labs, but didn’t commercialize it, Microsoft (MSFT 0.00%↑) did, using Xerox’s ideas.

Sears built a retail empire protected by its catalogue and real estate, but those walls meant it was slow to embrace e-commerce, and it lost out to the Amazons of the world.

In each case, leaders were protecting something. A successful product, a way of operating, a market position. And they built walls (strategic or mental) to keep threats out. But those same walls prevented them from seeing the future, partnering with new innovators, or doing the scary but necessary things to evolve. By the time the threat breached the walls, the companies were out of time.

In business, as in life, stagnation is the silent killer. A fortress can easily become a grave if you hide in it for too long. Warren Buffett uses “moat” as a positive term, and he loves companies with strong moats. But even Buffett would agree that a moat isn’t worth much if a company refuses to update its castle. A static moat can give a false sense of security.

Meanwhile, a competitor with a new method of attack (new technology, new business model) can render that moat irrelevant. The lesson for us is to watch out for businesses that grow too comfy behind their defences. If you hear a CEO say, “We don’t worry about [new trend]; our business is untouchable,” alarms should go off. Often, that’s exactly when the trouble is coming.

Anheuser-Busch: The King of Beers Caught in Its Castle

One of the most striking examples of this principle is the story of Anheuser-Busch, the brewer of Budweiser. Once proudly known as “The King of Beers.” For over a century, Anheuser-Busch (AB) dominated the American beer market. It had an extensive distribution network, deep advertising budgets, and fierce loyalty from drinkers who wouldn’t touch anything but Bud and Bud Light. By the early 2000s, AB had a roughly 50% market share in the U.S. beer market. To many, it seemed unassailable, a castle surrounded by thick walls of brand power and market muscle.

But those very walls began to imprison the company’s thinking. Leadership at AB was notoriously inward-focused. The Busch family, who ran the company for generations, was proud and protective of their American stronghold. Budweiser was an American icon why concern itself too much with far-flung markets?

While competitors were merging and expanding globally, AB largely stayed within its safe U.S. domain (aside from some minority stakes like one in Mexico’s Modelo). In the 2000s, a new threat was rising outside AB’s walls: a Belgian-Brazilian brewing conglomerate called InBev. InBev was the product of aggressive expansion. Belgium’s Interbrew (owner of Stella Artois, etc.) had merged with Brazil’s AmBev, which itself was the creation of some very bold, cost-cutting moves by Jorge Paulo Lemann, a Brazilian entrepreneur. He had global ambition written in his DNA.

There’s an illuminating anecdote from the early days of InBev’s rise. As the story goes, one of the Anheuser-Busch executives (reportedly from the Busch family) met with Jorge Paulo Lemann. The AB executive, perhaps seeing AmBev as a small regional player at the time, offered to buy the Brazilian brewer out for a pittance (one version of the tale says $10 million, essentially a rounding error for AB). It was a lowball offer meant to swat away a potential rival.

Lemann refused. Legend has it he smiled and said something to the effect of, “No, thanks, in a few years, I’ll be buying you.” It sounds like a movie script, but it did come true. AmBev kept expanding, merging into InBev with the European brands. They breached the walls of AB’s fortress not with a direct assault, but by outgrowing and outflanking it globally.

By 2008, Anheuser-Busch found itself in a vulnerable position. The company was still acting like the king of the hill, but it hadn’t expanded overseas, and its growth had stalled. Meanwhile, InBev was hungry to become the world’s biggest brewer and saw Budweiser as the crown jewel. In a dramatic takeover battle detailed in the book Dethroning the King, InBev launched a hostile bid for Anheuser-Busch.

AB’s leadership was caught flat-footed. The proud King of Beers realized its walls weren’t high enough after all. The Busch family owned only a tiny fraction of the stock (around 4% ), so they couldn’t block the deal. Many employees and loyalists were shocked. They had assumed the company’s heritage and dominance made it untouchable. But business is business: by the end of 2008, Anheuser-Busch was forced to agree to a takeover, and AB InBev (BUD 0.00%↑) was born as the new global brewing giant.

When I joined Labatt, the Canadian subsidiary of AB InBev, in 2009 as my first job out of business school, the merger was still fresh. Inside the halls, the story of the Busch family’s $10 million offer to Lemann was still being told like folklore, a reminder of how quickly power had shifted.

I also got a firsthand look at how the Brazilians ran the show. In those early days, InBev cut the low-hanging fruit: corporate jets were sold, executive perks like chauffeurs and country club memberships were slashed, and whole layers of staff were trimmed.

Then came the fine-tuning.

We began rolling out Zero-Based Budgeting (ZBB), forcing every team to justify expenses from scratch each year. Even sacred cows like Budweiser’s big marketing spends were no longer taken for granted. The message was clear: nothing was untouchable.

It’s a classic case of insularity leading to downfall. AB spent decades reinforcing its U.S. walls. Intense lobbying to keep beer distribution tightly controlled, heavy marketing to cement its brands, and a refusal to diversify much internationally. Those tactics protected AB for a long time, but also made it complacent. When a determined outsider appeared, AB had no international buffer and no agile response. The fortress fell from within. The “invaders” didn’t storm the gates with an army; they simply bought the castle from the bewildered inhabitants.

The AB story is a reminder not to be seduced by a company’s seeming invincibility. A dominant market position can lull management (and shareholders) into thinking nothing can change. But all it takes is a smarter or bolder rival with a different approach to turn yesterday’s moat into today’s trap. In Anheuser-Busch’s case, the walls they put up to protect their domestic stronghold eventually locked them out of global growth and left them vulnerable to a takeover.

The king was indeed dethroned.

Entel: A Local Giant Behind High Walls

I witnessed a similar dynamic firsthand during my time at Entel, a leading telecom company in Chile. Entel was the top dog in the Chilean mobile and telecom market for years. Geographically, Chile is a bit like a natural fortress: the Pacific Ocean to the west, the Andes mountains to the east. Perhaps taking a cue from the landscape, Entel’s leadership developed a kind of fortress mentality.

The market was essentially an oligopoly (a few big players: Entel, Telefónica’s Movistar and Claro). We were very comfortable in our position. The thinking internally was that international competition wouldn’t break into Chile. After all, it’s a relatively small country at the end of the world, and any outsider would have a hard time overcoming the barriers (both natural and regulatory). This was our unspoken “wall.”

Because of this confidence, Entel did something that, in hindsight, was short-sighted: instead of aggressively reinvesting profits to modernize and fortify the network (the smart way to build a wall), the company paid out fat dividends and kept business as usual. The implicit belief was, “Our moat is secure, why spend heavily? Enjoy the profits.” It felt good until an unexpected invader breached the walls.

Around 2015, a new player called WOM entered the Chilean mobile market. WOM was backed by European investors and led by a bold British CEO. They were scrappy and aggressive, offering cheaper plans and cheeky marketing that appealed to underserved customers.

Practically overnight, WOM started stealing market share from the complacent trio of incumbents. Entel, in shock, had to respond by slashing prices. The nice castle-on-the-hill existence was being disturbed.

The irony here is painful. Entel actually had a chance to block WOM’s entry before it happened, and at a very low cost. WOM’s launch in Chile was enabled by acquiring spectrum (mobile broadband frequencies) from Nextel, a small carrier that was exiting the market. Entel could have bought that spectrum itself when Nextel was selling it. Likely for a bargain (indeed, Nextel Chile was sold for roughly $30 million in total).

Some at Entel argued we should grab it, even if just to keep potential rivals out. However, the counter-argument prevailed: that the regulators wouldn’t allow Entel to hoard more spectrum (a possible antitrust issue), and that trying to buy it could be messy.

In reality, even if regulators might have scrutinized it, that process would have taken years. Years in which a competitor like WOM couldn’t enter.

What happened? WOM bought that spectrum, entered the market with fanfare, and gave us the fight of our lives. To compete, Entel had to spend many multiples of that $30 million to retain customers. We lost revenue as we had to cut prices and watched our market share shrink. The stock price of Entel, once steady, went on a downtrend due to the heightened competition and eroded margins.

All this pain might have been prevented by a small, proactive risk: stepping outside our comfort zone to preempt a threat. But the walls of complacency (“we’re safe, we’re Chile’s biggest, nothing to worry about”) ended up imprisoning our strategic thinking. By trying to avoid a minor fight (over spectrum purchase), we invited a major war on our home turf.

Never assume your market position is unassailable. Don’t let geographical, regulatory, or legacy advantages make you lazy. Competition finds a way. The Pacific Ocean didn’t stop a hungry competitor from sailing in (metaphorically, in our case). A smart company should be vigilant, a bit paranoid even, and willing to act boldly to protect itself, ideally by improving and innovating, not by standing pat. Entel’s walls were mental as much as anything: a belief that “it can’t happen here.” I learned that it absolutely can, and will, happen here if you invite it by standing still.

Breaking Free: How to Avoid Becoming a Prisoner of Your Own Protection

We’ve seen how walls can become traps. So how do we mitigate this issue? How can we protect ourselves (or our companies) without self-imprisonment?

Adopt a Growth Mindset (Stay Open)

The first step is mental. Embrace the idea that change is not automatically your enemy. In psychology, a “fixed mindset” tries to fortify what is, often by building walls to keep everything stable. A “growth mindset,” by contrast, is open to learning and adapting. In practice, this means regularly asking yourself or your business: What could we do better? What new thing should we try, even if it’s scary? Mindset by Carol Dweck talks about the fixed and growth mindsets.

Don’t become so defensive about your current success that you fear trying anything new. Encourage dissenting opinions and outside perspectives. They are like fresh air coming over the walls, preventing the staleness of groupthink.

Be Willing to Cannibalize Your Own Comforts

One of the most powerful antidotes to wall-building is a willingness to disrupt yourself.

Steve Jobs said,

If you don’t cannibalize yourself, someone else will.

This was the philosophy behind Apple making the iPhone, knowing it would kill the iPod. It takes courage to undermine your own prior success. But doing so on your terms beats having a competitor do it on theirs.

For investing, the parallel is to embrace calculated risks. Don’t cling to a strategy that worked in the past when evidence shows the world is changing. It might feel like sawing a hole in your own wall to climb through, but that’s better than sitting behind it until it crumbles.

Build Gates, Not Just Walls

Protection is not about hermetically sealing yourself off. It’s about controlled openness. Think of a medieval castle. The really smart ones had gates and drawbridges. They could let traders and allies in while keeping enemies out.

It means being open to partnerships, acquisitions, or new ideas from outside, rather than an NIH (“not invented here”) attitude. It might mean investing in a small disruptive startup in your field (inviting them in through the gate) so you can learn and benefit, instead of fighting them at the walls. By having gates, you ensure you’re never completely cut off from the flow of new knowledge and opportunities.

Keep Some Wall-Builders, but Add Wall-Breakers to Your Team

It’s good to have cautious people focused on protecting the core. But you also need voices that challenge the status quo (the folks ready to take a sledgehammer to a wall if it’s in the way of progress).

This can mean having independent board members or advisors who aren’t steeped in the company Kool-Aid. People who will ask, “What if our safe approach is actually risky?” It could mean friends or mentors who encourage you to step outside your bubble. If everyone around you only says, “Yes, stay safe, you’re right,” you might need to seek out a contrarian viewpoint or someone with more bold experience.

Learn from History and Others

We’ve discussed historical and business examples; use them!

If you’re a CEO, read case studies (like the ones above) with your team and ask, “Are we at risk of this?”

When I invest in a company, I like to check management’s tone: do they acknowledge disruption risks, and do they learn from others’ mistakes?

The wisest leaders almost have a bit of paranoia. Andy Grove of Intel titled his book “Only the Paranoid Survive.” That kind of watchfulness keeps you from relaxing too much behind your moat.

Remember times when playing it too safe backfired on you, and let that inform your future choices. It’s often said that comfort and growth do not coexist.

Invest in Adaptability (Not Just in Reinforcement)

If you have resources to allocate, don’t put 100% of them into shoring up the present. Devote a portion to exploring the future.

This means R&D, experimental projects, skunkworks teams, or even small acquisitions of emerging tech. Google allowed employees 20% time to pursue side ideas (some of which became Gmail and Google Maps). That’s a way of saying “we refuse to be stuck in our current model; we’ll keep evolving.”

Adaptability might mean diversifying your portfolio or learning about new asset classes or industries rather than saying “I only stick to what I know.” It could mean picking up a new skill or hobby periodically, to ensure you’re always expanding your world, not narrowing it.

Plan for the Worst-Case, Then Do the Best-Case

There’s a balance here. I’m not suggesting recklessness. Good risk management is still important; you don’t tear down all the walls and expose yourself to every storm. Instead, imagine the worst-case scenario if you open up or change, and prepare some cushion or response for it.

But also imagine the best-case scenario (the opportunity that might come), which often far outweighs the risk. For example, a company might say, “If we invest in this new product, worst-case it fails and we lose $X, which we can handle; best-case, it ensures our future for the next decade.”

Often, we overestimate the former and underestimate the latter. By clearly defining both, you realize that staying barricaded might actually be riskier. Preparation lets you open the gate without being blind to dangers.

Regularly Re-evaluate Your Walls

Make it a habit to audit your walls. Ask: “Is this wall still serving me, or has it become obsolete? Am I protecting the right things, in the right way?”

This applies to emotions (maybe walls you put up after an old trauma that you’re strong enough to take down now) and to businesses (maybe a regulation you relied on for protection is shifting, or consumer tastes are changing). The world changes, and so should your defences. A wall that worked yesterday might need a gate today or might need to be moved entirely.

By scheduling this kind of reflection, you avoid the trap of set-and-forget defences.

Finally, a tool that’s more mindset than anything:

Cultivate the confidence to live without walls

The Stoic philosophers, for instance, often practiced imagining life if their comforts were taken away, to remind themselves they could endure. It’s empowering to realize that even if some of your walls fell, you’d find a way to manage.

This translates to not over-leveraging on a single idea. You position yourself so that if one thesis fails, you’re bruised but not broken, ready to try the next thing.

It means knowing I’ll be okay if I take this chance. When you have that inner confidence, you rely less on rigid external walls for security. You become more flexible, like bamboo that bends in the wind rather than an oak that snaps.

Conclusion: Venture Beyond the Walls

“The walls you put up to protect yourself work to imprison you.”

It’s a simple sentence, but one worth meditating on in our decisions. Protection and prudence have their place. I’m not advocating naive exposure to danger. But we must be mindful of the line between prudence and paralysis. Walls should guard, not cage. The moment we start serving the wall instead of it serving us, we have a problem.

As I write this, I think about the companies in my portfolio and in the news. Which are building healthy, flexible defences, and which are retreating into a fortress of denial? I want the former in my corner. I want leaders who know when to open up and adapt, not just entrench.

Similarly, in my personal journey, I strive (imperfectly, I’ll admit) to keep an open mind and heart. To not let past failures or fears build a permanent wall around what I’m willing to try next. Some of the best experiences in my life and best investments in my career have come when I stepped outside the comfort zone, when I lowered the drawbridge and said, “Let’s give this a shot,” rather than reinforcing the status quo.

What about you? Have you ever had a moment where stepping outside your “walls” paid off?

Portfolio Update

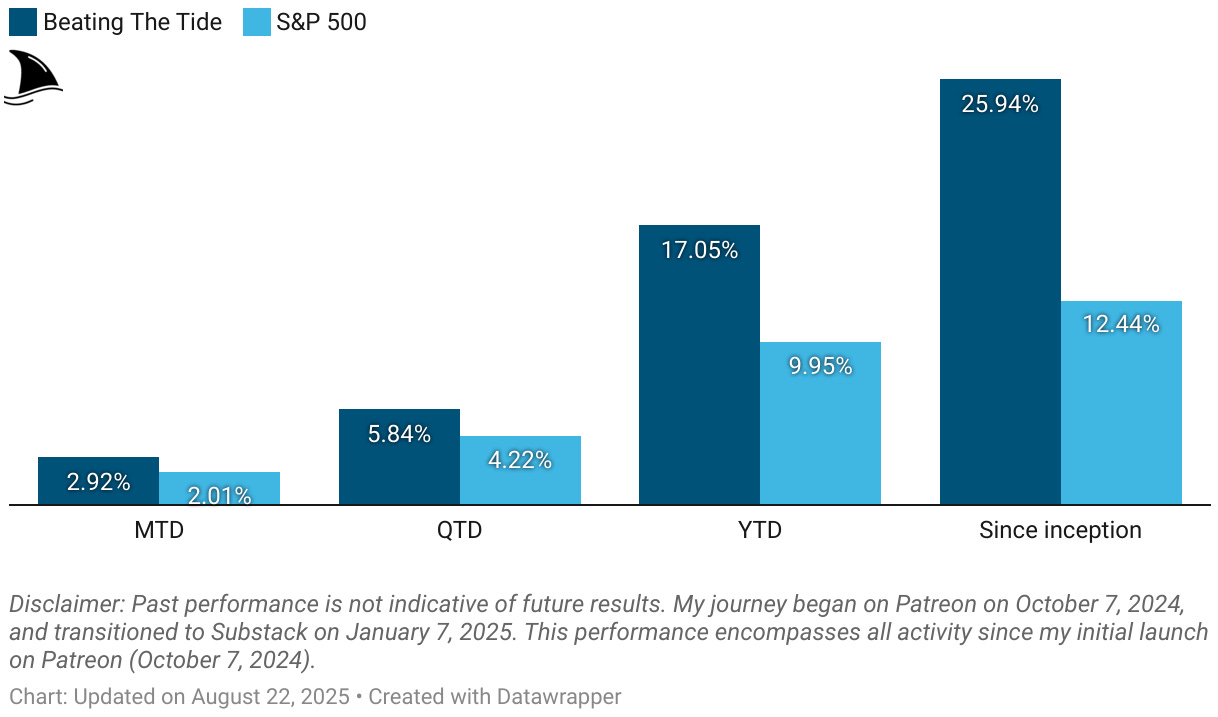

The portfolio moved higher this week.

Month-to-date: +2.9% vs. the S&P 500’s +2.0%.

Quarter-to-date: +5.8% vs. the S&P 500’s +4.2%.

Year-to-date: +17.1% vs. the S&P’s +10.0%, a gap of 710 basis points.

Since inception: +25.9% vs. the S&P 500’s +12.4%. That’s 2.1x the market.

Portfolio Return

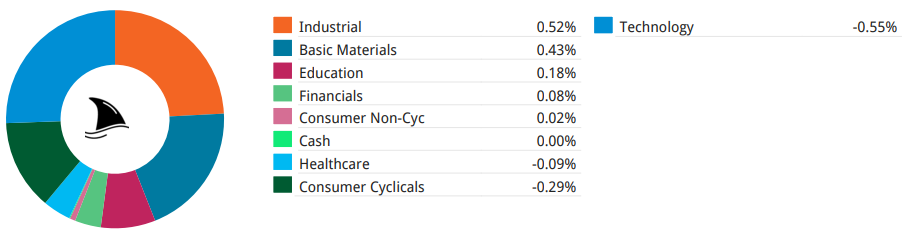

Contribution by Sector

Industrial, gold and education led the gains, partially offset by tech and consumer cyclicals.

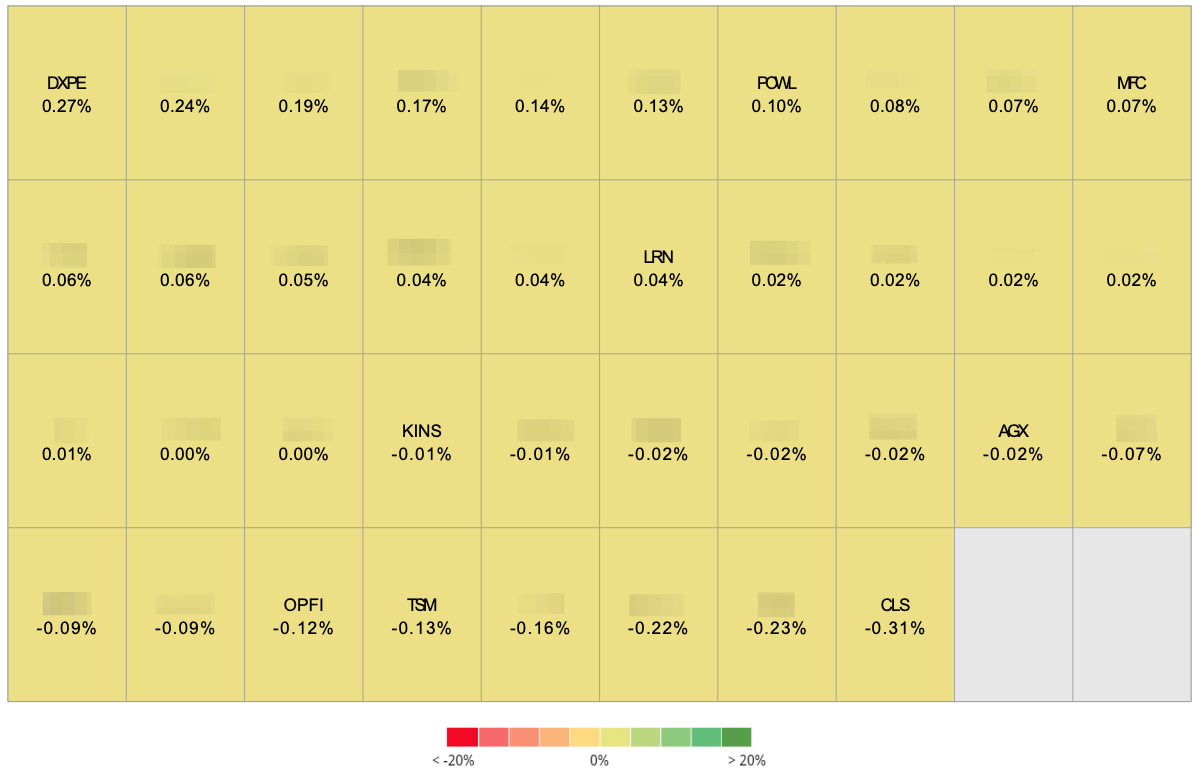

Contribution by Position

(For the full breakdown, see Weekly Stock Performance Tracker)

+27 bps DXPE 7.67%↑

+10 bps POWL 4.38%↑

+7 bps MFC 0.00%↑ (TSX: MFC)

+4 bps LRN -1.37%↓

-1 bps KINS 0.00%↑

-2 bps AGX 0.00%↑

-12 bps OPFI 0.00%↑

-13 bps TSM 0.00%↑

-31 bps CLS 0.00%↑ (TSX: CLS)

That’s it for this week.

Stay calm. Stay focused. And remember to stay sharp, fellow Sharks!

Further Sunday reading to help your investment process: