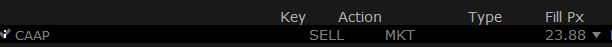

Time to Lock In CAAP Gains

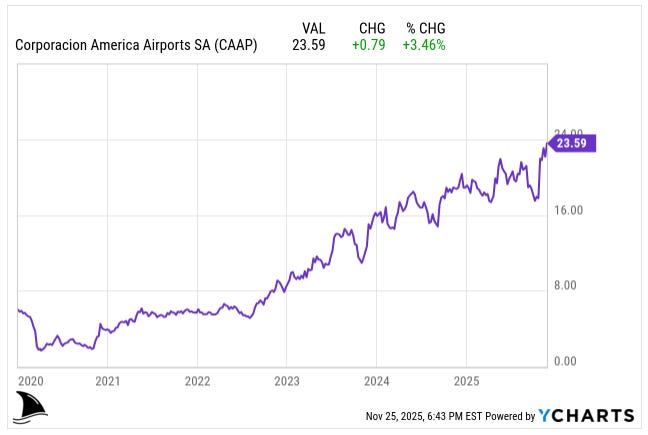

Deep dive stock analysis. After 52% gains on CAAP, I explain why it’s time to lock them in.

Trade alert:

Close CAAP position

I’ve been into airport investing since my days at Moneda Asset Management, where I cut my teeth analyzing Aeropuertos Argentina 2000 (AA2000) bonds. I’ve flown through Argentina and Brazil and remember landing at Ezeiza and Congonhas, noting how pivotal these hubs are.

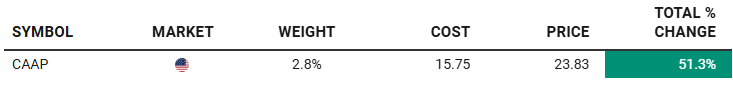

When I launched this newsletter, I started adding Argentina plays. I bought into Grupo Supervielle (SUPV) and Corporación América Airports (CAAP) early in 2024 as Argentina reopened. SUPV ran up +74%, and I sold it in January 2025.

SUPV was up and facing big resistance; locking in profits was prudent in hindsight.

CAAP is up +51.6% since we added it.

I kept that position open to see how the story plays out. But I’m beginning to see cracks. Argentina is a wild runway. Soaring one minute and stalling the next. My mantra has been that with Argentina you want to be “in and out.”

In other words, capture gains quickly; riding too long can invite turbulence. Given new risks ahead, it’s time to redeploy CAAP’s 52% gain.

This analysis explains why I’m pressing the eject button on CAAP now.

Table of Contents:

TLDR

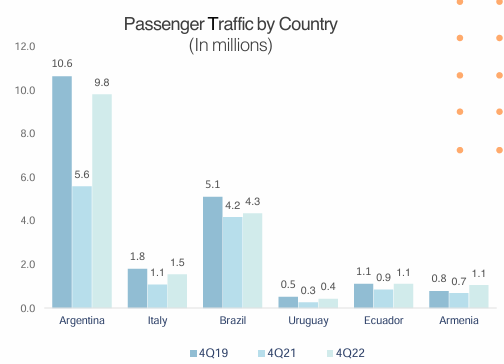

CAAP is a huge Argentina-focused airport operator (37 airports in Argentina, 8 in Uruguay, 1 in Brazil and 2 in each of Italy, Armenia and Ecuador).

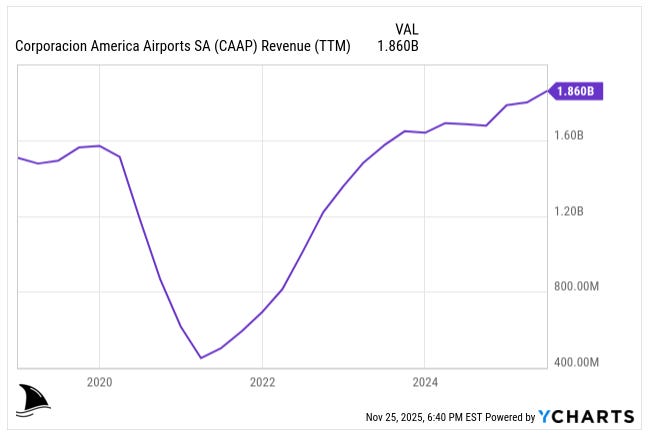

Its traffic and revenues have rebounded strongly post-COVID.

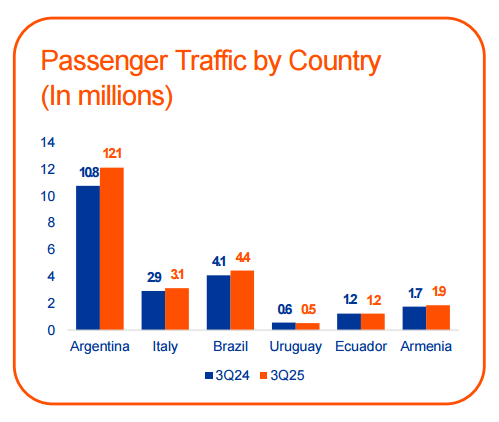

It blew past the old baseline in almost every country CAAP operates in. Argentina, Italy, Ecuador and Armenia all carry higher volumes today than in 2019, which is remarkable when you remember that 2019 was the global travel peak before the world shut down. Uruguay is also above its pre-COVID run rate when you adjust for the six-day runway closure this quarter.

The only laggard is Brazil, which sits slightly below its 2019 level because the local market recovered more slowly and airline capacity hasn’t fully normalized. The charts from CAAP’s filings make this clear: Argentina climbed from 10.6 million passengers in 4Q19 to 12.1 million in 3Q25, Italy from 1.8 to 3.1 million, Ecuador from 1.1 to 1.2 million, Armenia from 1.0 to 1.9 million and Uruguay flat at 0.5 million. Brazil is the exception, at 5.1 million in 4Q19 versus 4.4 million in 3Q25.

Traffic strength like this tells me travelers came back early and never stopped. It shows the system is running hot rather than just recovering. Revenue followed the same path. You can see it in the TTM chart, which climbs from the COVID low straight past its 2019 levels and keeps rising.

This strength drove the stock to almost four times its pre-COVID level.

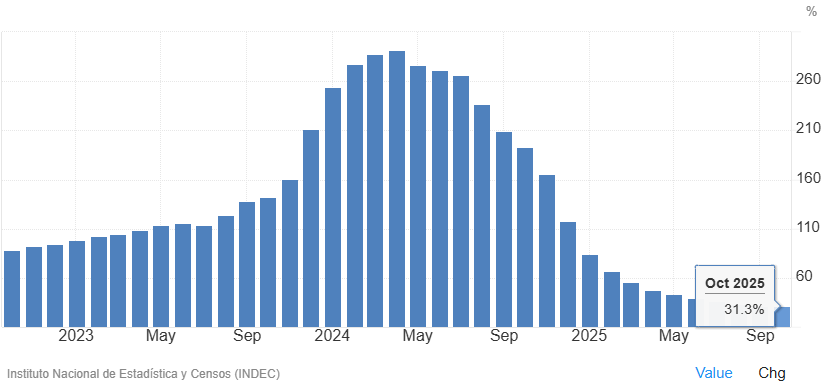

But the core business has low margins and high country risk. As I showed with SUPV, Argentina runs in waves. With inflation still high (+30%) and exchange rates volatile, I don’t want to weather the next storm.

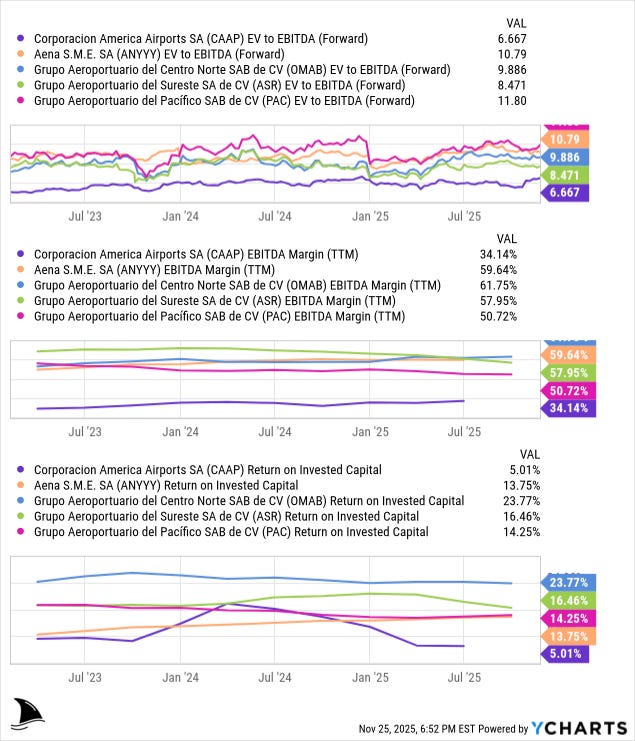

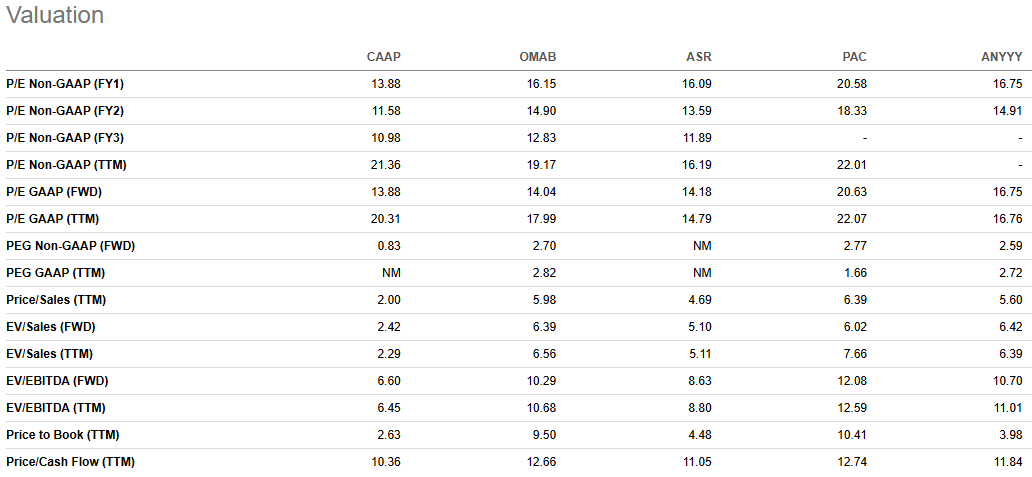

CAAP’s valuation has run up. It trades at historical peak multiples despite weaker profit margins than peers. Even though the shares are trading at peak valuation, they offer a discount to peers which is more than justified by the lower margin and lower ROIC.

Management is focusing on big capex plans (Italy and Armenia expansions of $1B each) which may dilute short-term cash flow. Competition is stiff: peers like Mexico’s OMAB/ASR have higher returns and steadier economics. CAAP also carries hefty concession fees and construction revenues (IFRIC12 accounting) that make its financials look healthier than core earnings. In short, CAAP’s good news is largely in the books. New threats loom in Argentina and globally.

I’m locking gains.

Company history & evolution

CAAP was created in 1998 when Martín Eurnekian’s family consortium won the AA2000 concession, granting them almost all major Argentine airports (through 2038). That deal included Ezeiza and Aeroparque in Buenos Aires plus dozens more.

Over the 2000s and 2010s, CAAP added other countries: two main airports in Uruguay (Carrasco/Montevideo and Punta del Este), two in Armenia (Yerevan and Shirak), two in Ecuador (Guayaquil and Galápagos), one in Brazil (Brasilia), and more recently Florence and Pisa in Italy. It even dipped into Mexico briefly.

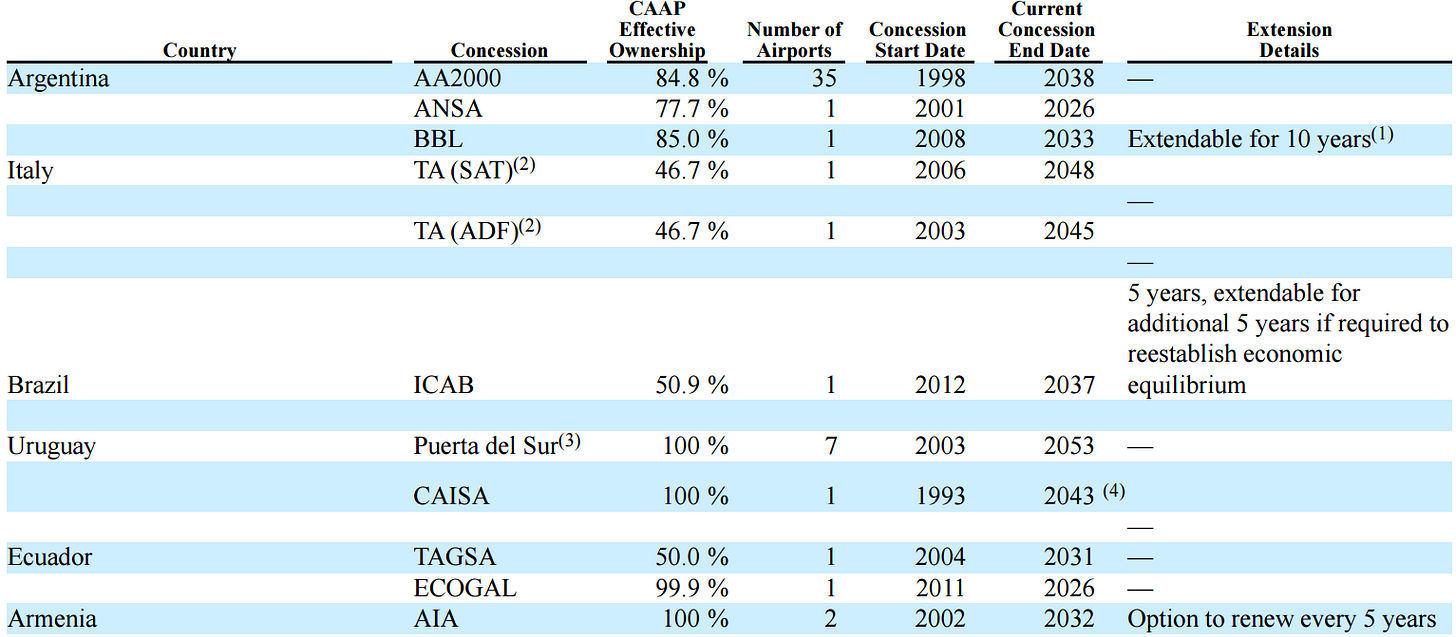

Today CAAP operates airports across six countries through a set of long-term concessions. In Argentina, it controls 35 airports under AA2000, plus two smaller concessions (ANSA and BBL), bringing its total in the country to 37. It runs two airports in Italy through SAT and ADF, one in Brazil through ICAB, eight in Uruguay across the Puerta del Sur and CAISA concessions, two in Ecuador through TAGSA and ECOGAL, and two in Armenia through AIA.

That footprint spreads its cash flows across several currencies although everything is reported in U.S. dollars. The weak Argentine peso, which has been losing value at a rapid pace, remains the biggest headwind to real returns.

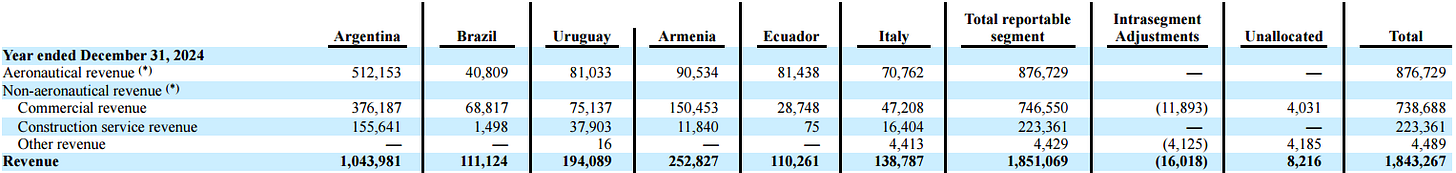

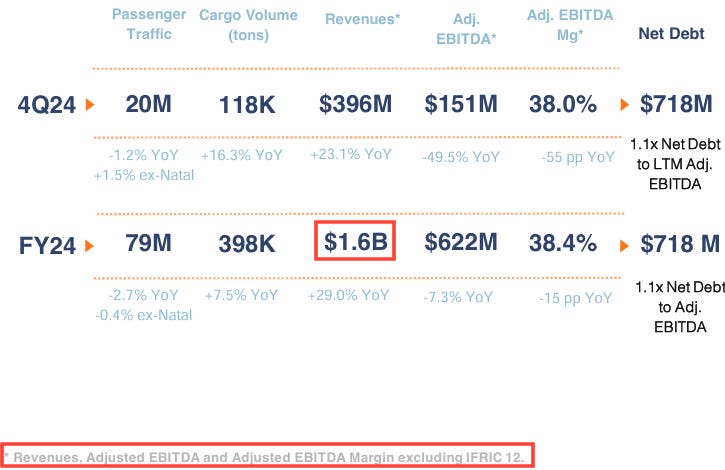

In 2024, CAAP had $1.84 billion in total revenue. Argentina generated 56% of the revenue followed by Armenia (14%), Uruguay (10%), Italy (7.5%), Brazil (6%), and Ecuador (6%).

These figures follow IFRS rules, which require CAAP to treat airport construction and expansion work as revenue under “IFRIC 12.” It is an accounting pass-through. The company builds a terminal, books the spending as revenue, and then books the same amount as cost. It does not reflect the actual economics of running airports.

Management knows this inflates the top line, so they strip it out when they talk about performance. In 2024, construction revenue was about $223M. After removing it, operational revenue was roughly $1.62B which is the real snapshot of landing fees, passenger charges and commercial activity.

The company is headquartered in Luxembourg (for tax/regulation reasons) but essentially run by an Argentine management team. CEO Martín Eurnekian (son of the founder) has steered the company’s expansion. The concession in Argentina runs until 2038, with Uruguay’s until 2043/53, Italy’s until 2045/48, and Armenia’s deals last into the 2032. Notably, CAAP sold its 50% stake in Peru’s Lima airport in 2021 and exited some smaller contracts to focus on core markets.

How it makes money

CAAP’s business is airport operation. That breaks into a few revenue streams under each concession:

Source #1. Aeronautical fees

These are regulated fees charged per flight or per departing passenger for airline operations, set by government-approved tariff formulas that aim to restore the concession’s economic equilibrium. The currency denomination of these fees varies significantly by passenger type and country.

Argentina (AA2000): Fees charged to international passengers are denominated in U.S. Dollars, such as the maximum rate of U.S.$57.00 per departing passenger at Category I airports. This structure is a key source of dollar revenue. However, fees for domestic flights are denominated in the local currency, the Argentine Peso (ARS), established at, for example, AR$5,685.00 for Category I airports as of November 2024.

Other Concessions: Currency exposure varies, but certain key segments are dollar-denominated or dollar-linked. For example, tariffs in Ecuador are denominated in U.S. Dollars, and passenger use fees for international flights in Uruguay are also set in U.S. Dollars (e.g., U.S.$58.00). Conversely, tariffs in Brazil are adjusted annually based on an inflation-based model (IPCA index).

For the year ended December 31, 2024, CAAP collected U.S.$876.7 million of Aeronautical Revenue. This accounted for approximately 47.6% of the total consolidated revenue in 2024. This category includes revenue derived from aircraft and passenger movement, such as fees for landing, parking, and passenger use of runways and terminals.

Source #2. Non-aeronautical (commercial) revenue

Airports also earn from shops, parking lots, rent, fuel fees, etc. Think duty-free shops, restaurants, luggage services, car rentals, and real estate rentals. CAAP calls this “commercial revenue.” In 2024 it was about $746.6M (roughly 40% of total revenue). That’s basically every traveler spending on food, goods, and paying parking. These fees are higher for international passengers in general, since they tend to spend more. CAAP actively expands duty-free areas and VIP lounges to boost these fees.

Source #3. Construction (IFRIC 12) (no real revenue)

This is unique to concession accounting. When CAAP builds or expands terminals or runways (investing in CAPEX), international accounting rules allow those construction costs to count as revenue over time (under IFRIC 12, a UN standard). In 2024, CAAP recognized about $223.4M from construction contracts. In plain terms, if CAAP is paid by the government to upgrade an airport, that flows through the income statement as revenue (and matched by construction cost). This inflates total revenue but doesn’t reflect cash flow the same way. (It’s similar to how toll road companies count highway construction as revenue.) Removing this, their “airport operations” revenue was $1.62B in 2024.

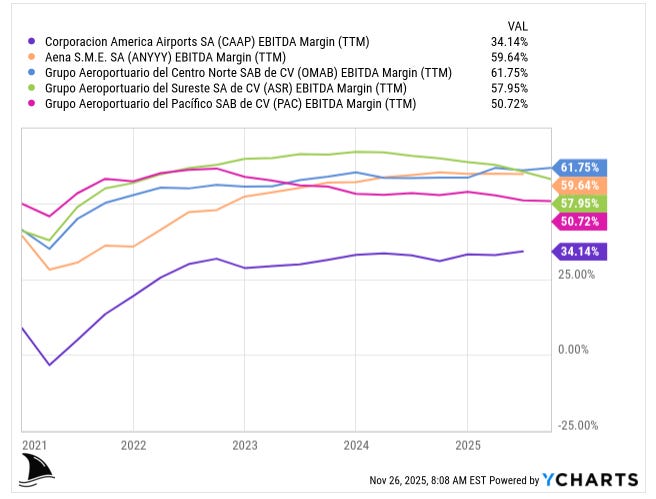

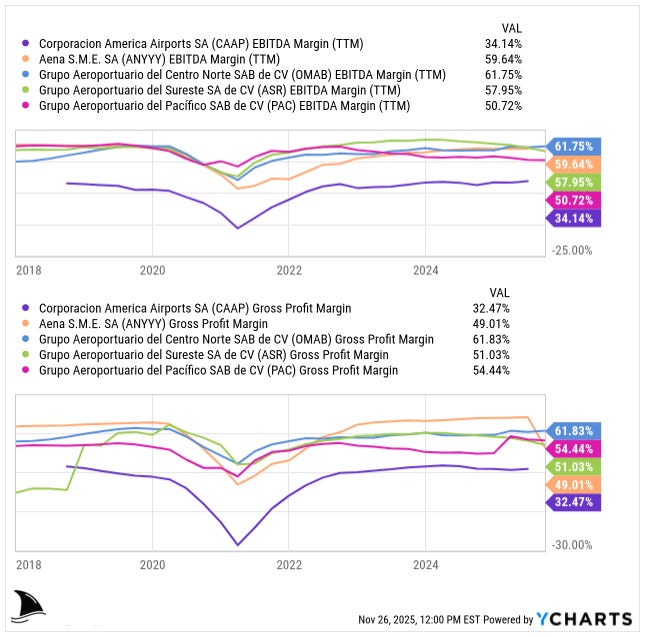

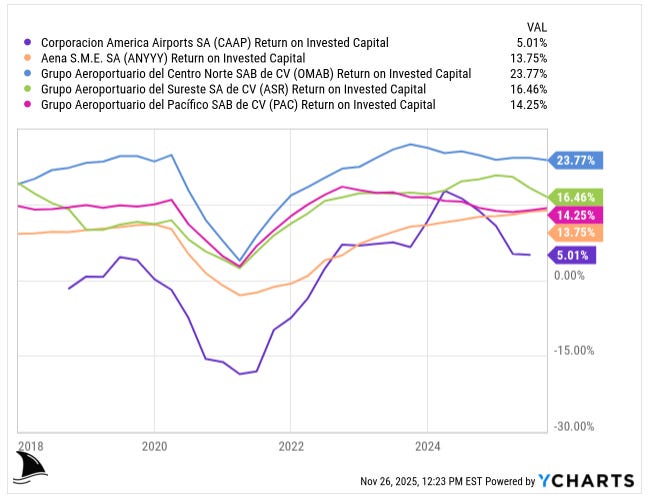

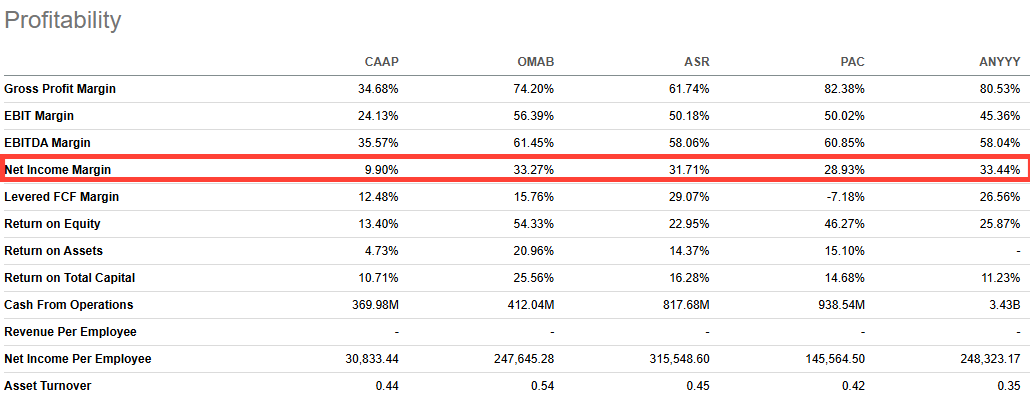

Margins: CAAP’s profitability trails peers. Its EBITDA margin sits near 34%, while Mexico’s OMAB and ASR run at 58–62% and PAC still sits above 50%. Even Aena in Spain holds close to 60%.

That gap reflects CAAP’s heavier cost base. It pays significant concession fees in Argentina and employs a large workforce there with wage inflation and social charges. On top of that, the IFRIC 12 construction activity adds revenue but also adds matching costs that dilute margins. Put simply, CAAP operates harder for every dollar of profit compared to its global peers.

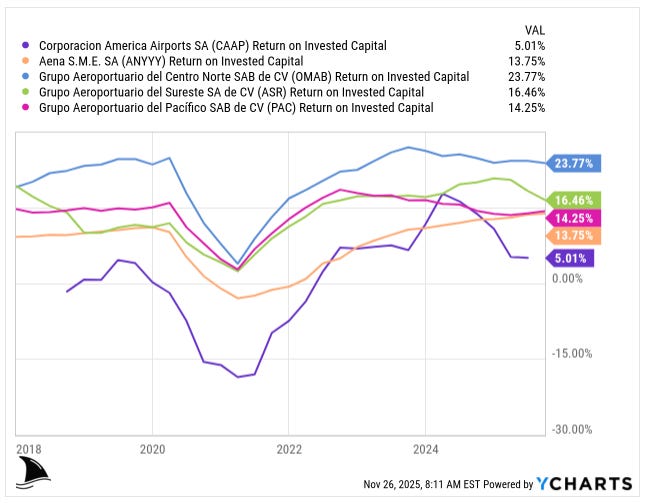

In sum, CAAP’s ROIC is relatively low.

This is driven by high operating costs in Argentina, where inflation rapidly escalates peso-denominated expenses, particularly wages. Although core revenues, such as international passenger fees (U.S.$57.00), are dollar-denominated, the Argentine concession’s ability to maintain its guaranteed economic equilibrium (a target IRR of 16.45%) is compromised by the regulator (ORSNA), which has consistently lagged in approving necessary tariff and investment adjustments (some disputes dating back to 2018–2023), thereby compressing realized returns.

Fees per passenger

CAAP tracks revenue per passenger. Aeronautical fees in Argentina are $5–6 per passenger currently (plus a share of cargo fee). Commercial spend (duty-free, etc.) adds roughly $9–10 per passenger on average, depending on airport. They try to raise these with inflation formulas. In Q3 2025, CAAP noted revenue per passenger climbed “reflecting success of our commercial initiatives”.

Key metrics (Q3 2025)

Passengers 23.3M (9.3% y/y), cargo -3.4%, flights +6.9%. Aeronautical revenue $246M; commercial $227M; total rev ~$532M (including ~$55M from construction). Operating income was $147M in Q3 vs $100.9M a year ago. Adjusted EBITDA (ex-IFRIC) hit record $194M, up 34%, with margin 41.2% vs 35.9% prior. These numbers were boosted by recovering traffic and high inflation “popping” costs from last year.

Industry and growth outlook

The airport industry is tied to travel trends. Globally, air travel has rebounded strongly after the COVID slump. International tourism and business travel are past pre-pandemic levels in many markets.

CAAP’s traffic is climbing

They reported passenger traffic +9.3% in Q3 2025. In January 2025 alone, traffic in Argentina jumped 9.5% with international traffic surging 22% in Argentina. (International fliers spend more, so that’s a good sign for revenues.) Lower fuel prices compared to 2022 also helped airline schedules.

Latin America growth

Mexico’s airport operators (OMAB, ASR, PAC) are seeing double-digit traffic growth and 15-20% revenue growth. Brazil and Argentina were slower, but Argentina has turned the corner as its economy stabilized under new reforms. Vacation travel within the region is up. On the other hand, Latin economies remain volatile (inflation, currency swings, debt issues). Big macro changes (like policy shifts or devaluations) can swing demand suddenly.

Long term, CAAP has growth catalysts

It can lift tariffs with inflation in most countries, and new routes or airlines always pump more traffic. For example, that Uruguay concession automatically raises tariffs using a mix of U.S. inflation and Uruguayan inflation. Projects underway (expanded terminals in Armenia, more duty-free in Uruguay) should boost ancillary revenue.

However, threats abound.

Global risks like oil spikes or new travel restrictions could dent demand. Latin politics can be unpredictable: government changes might renegotiate fees or introduce taxes (we saw talk of Argentine airlines paying 70/30% fare splits). Sector competition is moderate; no new airports are easy to build. Unlike roads or banks, airlines pay the tab in airports, so airlines’ health matters. A big airline bankruptcy could hollow traffic.

All told, industry trends are positive but not without speed bumps. CAAP’s diversified footprint (now 60% international revenue) offers some cushion against any one country’s pain. But Argentina still drives most profits, so its cycle is key.

Competitive landscape

When you look at CAAP, you have to look at the rest of the “airport club.” The closest peers are the Mexican operators OMAB, ASR and PAC plus Spain’s Aena. They all run airport networks, collect aeronautical and commercial fees, and operate under long concessions. On paper the business models look similar. In practice they live in very different neighborhoods.

CAAP runs a mixed bag of airports. Argentina gives it a lot of volume but not always premium yields. Many routes are domestic, and the passenger base is more local than tourist. The Mexican operators lean harder into leisure and business travel from the United States and Canada. That means more international traffic, higher ticket prices and heavier duty-free spend. Aena sits in a different league again. It controls major European hubs like Madrid and Barcelona, which are magnets for high-spend international travelers. This mix matters because an international vacationer buying perfume at duty free is a better customer than a strapped domestic flier grabbing a coffee.

You see the result in margins. CAAP’s EBITDA margin is about 34%, while peers sit in the 50–62% range. Gross margins show the same pattern. CAAP runs at 32% gross margin, versus 62% at OMAB, 51% at ASR, 54% at PAC and 49% at Aena.

Even allowing for the fact that CAAP includes IFRIC-12 construction revenue (which inflates top-line) the impact is minor. Construction revenue, even at full scale, might add just 4–5 basis points to margin once you net out the matching costs. So the margin gap can’t be explained away by accounting treatment alone.

It’s reasonable to assume many of CAAP’s large airport peers also use concession-accounting under the same IFRIC-12 / IFRS 15 (or equivalent) framework when they report financials; that tends to be standard in regulated infrastructure concession businesses. The accounting standard for service concession arrangements (IFRIC 12) applies to operators globally when the government (grantor) controls infrastructure and grants a concession to a private operator to operate and maintain it under regulated terms.

That said I found no public disclosure from OMAB, ASR, PAC or Aena explicitly stating “we apply IFRIC-12 and report construction under it.” Each company uses its local accounting standards, which may mirror or approximate IFRIC-12 but might differ in details (for example, financial-asset model vs intangible-asset model, timing of asset recognition, use of hybrid models, local variations in IFRS adoption). Because of that I cannot prove those peers record construction revenue the same way CAAP does.

Therefore it remains fair to treat CAAP’s margin gap as real and not just an artifact of accounting. CAAP earns less per dollar of revenue compared with its peers.

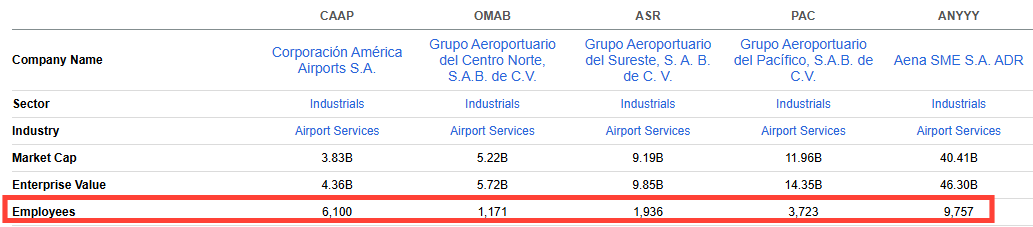

They all collect similar kinds of fees. The difference is unit economics. CAAP pays heavier concession fees to governments, carries a larger local workforce and operates in inflation-prone markets where costs move fast. It employs about 6,100 people, fewer than Aena’s 9,757 but far more than the Mexican peers.

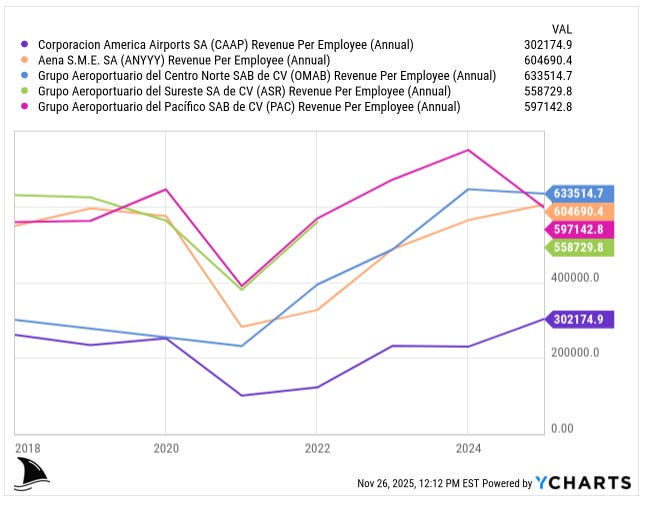

That is why revenue per employee is roughly half of peers.

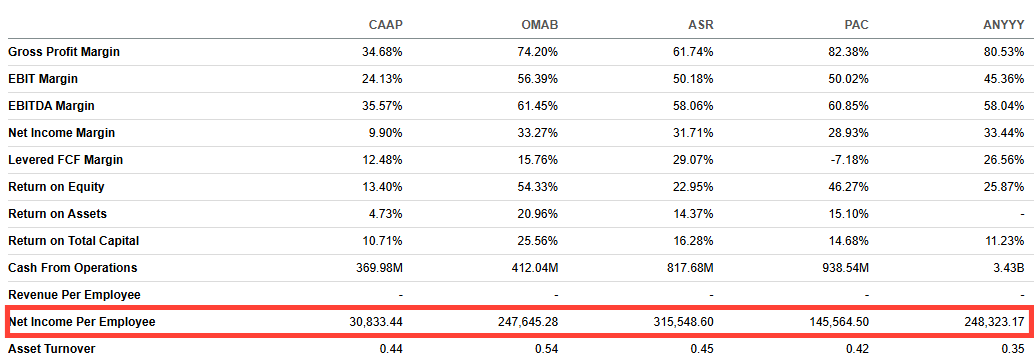

And that naturally impacts the bottom line. Net income per employee is only 10% to 20% of what peers produce.

If you are wondering why the hit gets larger at the net income level, it comes from operating leverage and financial leverage. I explained those in detail here if you want to go deeper.

More people per dollar of sales usually means lower margins.

Returns on capital tell the same story. CAAP earns only about 5% ROIC today. Its peers earn much more on every dollar they invest. OMAB sits near 24%, ASR and PAC are both around 14–16%, and Aena is just under 14%. The gap is obvious when you look at the lines. CAAP stays near the bottom of the chart. The others climb back toward their pre-pandemic peaks.

Some of that gap is country risk. Mexico and Spain have more stable inflation and stronger currencies. Regulators there tend to honor long-term tariff formulas. Argentina and some of CAAP’s smaller markets can change the rules mid-game. That keeps returns in check.

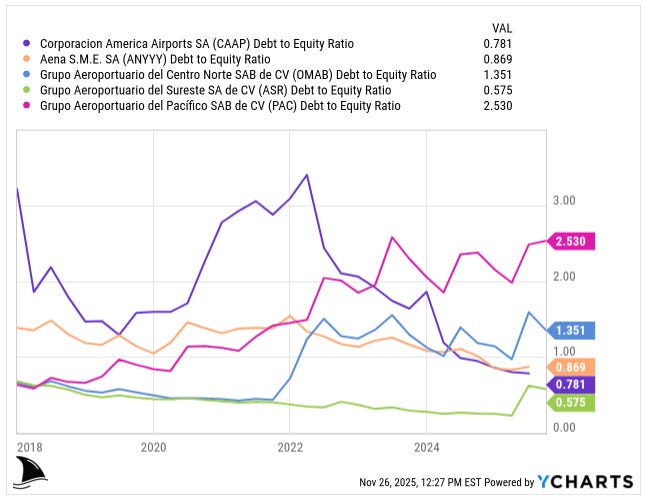

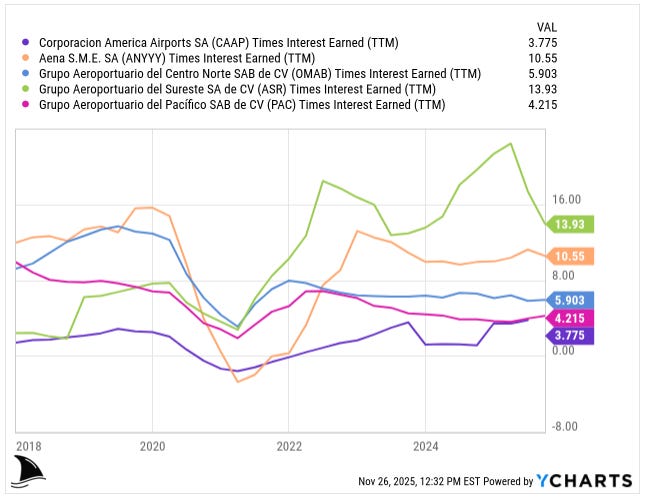

On leverage and risk, CAAP looks conservative at first glance. Its debt-to-equity ratio is about 0.78x, lighter than OMAB at 1.35x and PAC at 2.53x, and roughly in line with Aena at 0.87x. ASR is the most conservative at 0.58x.

The catch is coverage. CAAP’s interest coverage is just 3.8x slightly below PAC’s 4.2x. OMAB covers interest about 6x, Aena about 11x, and ASR over 14x.

In other words, CAAP has less financial flexibility even though it is not wildly levered. A shock to earnings hits CAAP’s coverage much harder than it hits its peers.

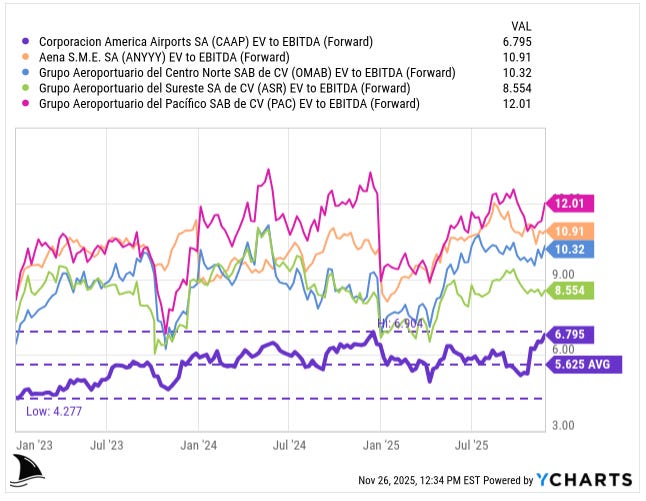

Valuation is where CAAP still looks interesting. It trades at about 6.8x forward EV/EBITDA, which is a discount to peers.

Even so, CAAP is no longer cheap on its own history. The stock now trades right near its all-time peak multiple of roughly 6.9x. In other words, the catch-up trade already played out. The discount versus peers stays, but the margin of safety inside CAAP’s own valuation has shrunk.

On a simple multiple basis, CAAP is the cheapest airport operator in the group.

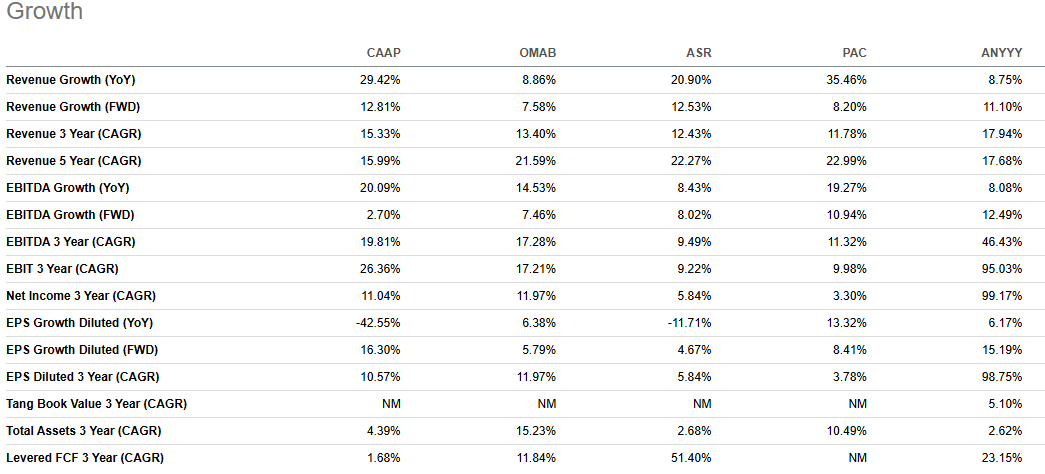

Growth sits somewhere in the middle. CAAP’s recent revenue growth looks strong at almost 30% y/y, ahead of OMAB and Aena and just behind PAC. Three-year and five-year revenue CAGRs are in the mid-teens, broadly in line with peers.

The problem is that CAAP converts less of that growth into bottom-line value. Its net margin is just under 10%, compared to 29–33% for OMAB, ASR, PAC and Aena.

So a lot of the growth leaks out through costs, concessions and inflation.

So where does this leave CAAP competitively. In simple terms, CAAP is the high-beta, lower-quality airport operator of the group. It benefits from similar secular tailwinds as its peers: more air travel, growing tourism and rising commercial monetization per passenger. It also offers the cheapest entry ticket on multiples. The flip side is that its airports sit in tougher jurisdictions with more volatile currencies and weaker frameworks. That reality shows up in lower margins, weaker returns on capital and thinner interest coverage.

Management & capital allocation

CEO Martín Eurnekian is one of Argentina’s wealthiest businessmen. He’s kept the company debt-light and cash-rich; CAAP had $540M cash on hand as of Q3’25.

That cash buffer is a strength, giving CAAP flexibility. They haven’t needed bailouts. Management has not paid dividends to common shareholders (they prioritize reinvestment).

Instead, cash flows go to debt reduction and new projects. For example, CAAP has no meaningful preferred share or bond defaults, and net debt/EBITDA 0.9x is pretty conservative for infrastructure.

Capital allocation

CAAP is plowing money into growth projects, especially in Europe and Asia. They’ve disclosed two big plans: in Italy, a €605M airport expansion at Florence and Pisa (Florence alone gets €497M by 2028); in Armenia, about US$425M of terminal upgrades by 2027. These are high-return projects if traffic forecasts hold up, but they’ll soak up cash and leverage in the near term. The payoff is longer term (+2026). There’s also routine maintenance capex each year (runways, systems), which was $235M total in 2024.

Management’s track record

So far so good on expansions. They handled the post-COVID rebound well. But we should remember that management’s goal is growth, not dividends. There’s no share buyback or big payout policy. The share stayed public, and insiders hold a controlling stake. They could theoretically take it private if they wanted. But for now, they are public and focused on building airports.

One small capital note

In late 2023 CAAP reorganized some Uruguay holdings (Navinten duty-free shop operator) to mostly keep cash in Argentina at holding level. It shows they are mindful of the tricky FX controls in Argentina. Still, ultimately Argentine subsidiaries need to channel profits out, which can be hindered by currency rules. In short, management is competent and cautious with debt, but they are committed to big projects rather than hoarding cash or cutting a dividend check.

Key risks

Investing in CAAP means taking on Argentina. Inflation and currency swings can erase gains fast, and the government has a history of stepping into price setting. Concessions are contracts that can be rewritten, and capital controls can trap cash. Even abroad, projects like Florence require regulatory approvals that move slowly. Airport expansions also carry execution risk. If traffic slows or airlines cut capacity, the returns on those projects drop.

There is a currency mismatch too. Costs are mostly in local currency while a chunk of revenue is in dollars. Hedging helps only so much. Add some competitive pressure in Italy, plus a thinly traded stock that can swing when big holders move, and the overall risk feels high. CAAP has good assets but operates in a volatile environment. After a solid 52% gain, I’d rather take the win and look for cleaner setups.

Verdict

CAAP has been a great run for us but I now turn cautious. We bought for growth and recovery, and we got it: traffic is back, revenues are up, and the stock is a 52% winner since inclusion in the portfolio. But the headlines are changing. Another jump in US rates or a peso crash could reignite Argentine inflation. Brazil, Uruguay and Italy help diversify, but the core is still Argentina, and she’s not out of the woods. The political winds could shift: remember how fast the weather changed for SUPV once Argentina’s rally peaked.

In short: I believe CAAP’s shares have appreciated to fair value given current info. The down-risk is higher than the up. To quote a metaphor: we’re at peak altitude and seeing storm clouds. It’s time to start descending (i.e. sell) and lock in the profit.

I am exiting CAAP now. I’ll redeploy that capital into new opportunities. The airport is signaling a safe landing, so I’ll take that.

Brilliant article! I have been selling Nov. Dec. Jan. $22.50 Calls as my slow exit strategy. Overall I like the airport operator space but CAAP appears near fully valued and without dividend or buyback I’m inclined to exit here.