PayPal Post-Mortem: Why I Sold PYPL and What Changed in the Investment Thesis

Q4 2025 exposed deeper weakness in PayPal’s core checkout business, forcing a reassessment of the moat, management execution, and long-term growth outlook.

Context for the image:

Lately I’ve been reading Elon Musk, and it reminded me how strange the PayPal origin story really was. Musk founded an online bank called X.com in 1999, then merged it with rival Confinity in 2000, a messy Silicon Valley shotgun wedding that eventually became PayPal.

Back then he already dreamed of building a universal financial platform, not just a payments button, and years later he is still chasing that same idea by trying to turn today’s X into an everything-app with banking, payments, and more.

Fast forward to now and the plot feels almost sci-fi again. Musk is actively merging pieces of his empire, even combining SpaceX with his AI company xAI in a deal valued around $1.25 trillion ahead of a potential IPO.

So when I joke that the “easy fix” for PayPal is for Elon to buy it, merge it into X, bolt the whole thing onto SpaceX, and IPO the monster at a trillion-plus valuation… it sounds ridiculous. But history suggests it is exactly the kind of loop-the-timeline move Musk loves to make.

My first stock pick for this newsletter was PayPal Holdings [PYPL 0.00%↑].

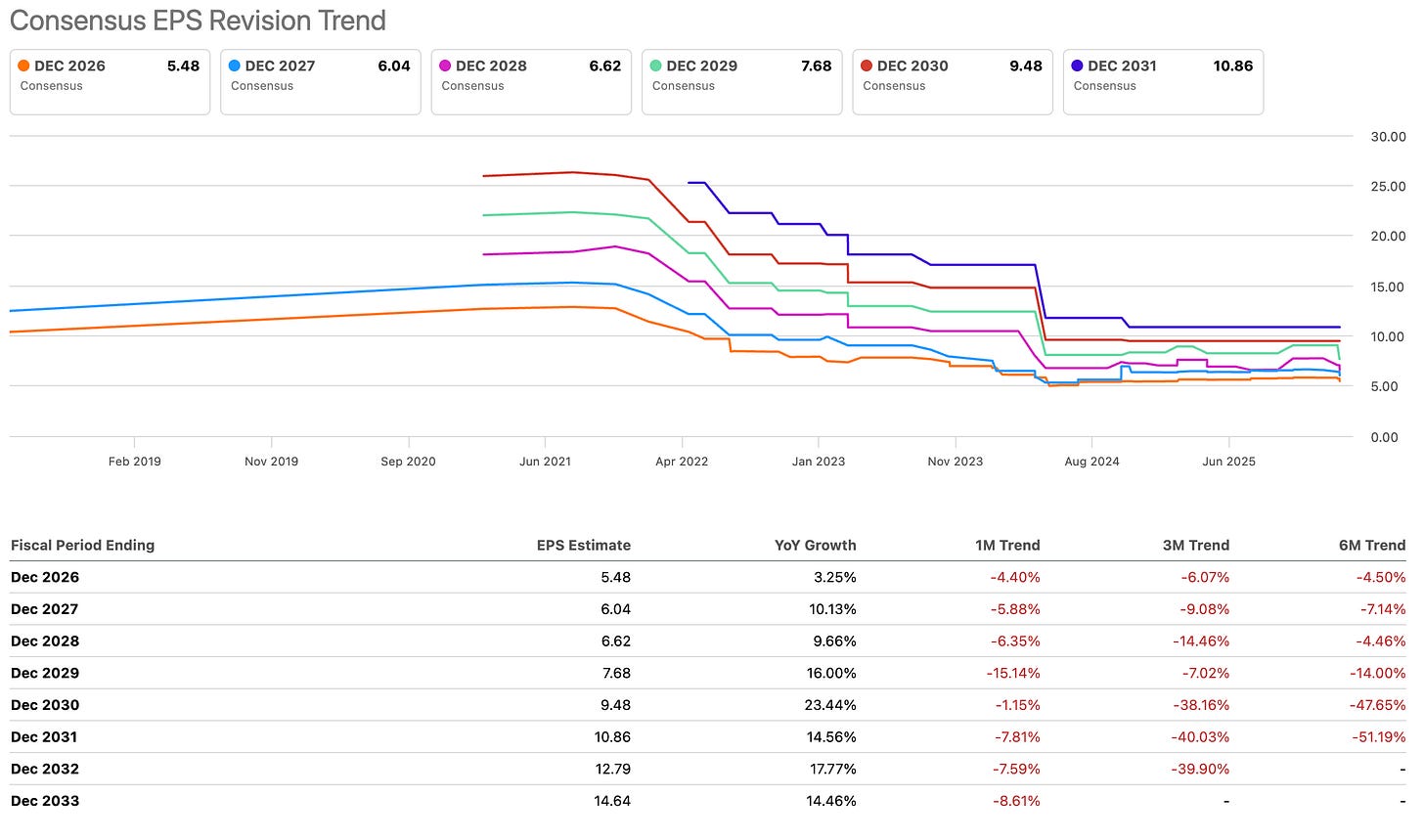

PayPal’s stock kept falling after my recommendation…

…and with each disappointing quarter, the “forward earnings” estimates also came down…

I’ve just closed out that position after the Q4 2025 earnings call, taking a 52% loss.

I usually don’t like selling a stock right after bad earnings news. In this case, though, the story changed so much that I decided to rip off the band-aid. Luckily, it was a small position (0.9% of the portfolio), so the damage is contained. I had actually warned paid subscribers earlier that I was reviewing my thesis on PayPal.

The disappointing Q4 results were simply the final straw.

Before I dive into what went wrong, let me be clear: PayPal could still eventually become a multibagger if it manages a successful turnaround. It still has that potential. But as of now, I view it as a speculative play rather than a high-conviction investment. Here’s a breakdown of why I sold, what happened in Q4 2025, and what I got right and wrong in my original thesis on PayPal.

Table of Contents:

Q4 2025: The Final Straw

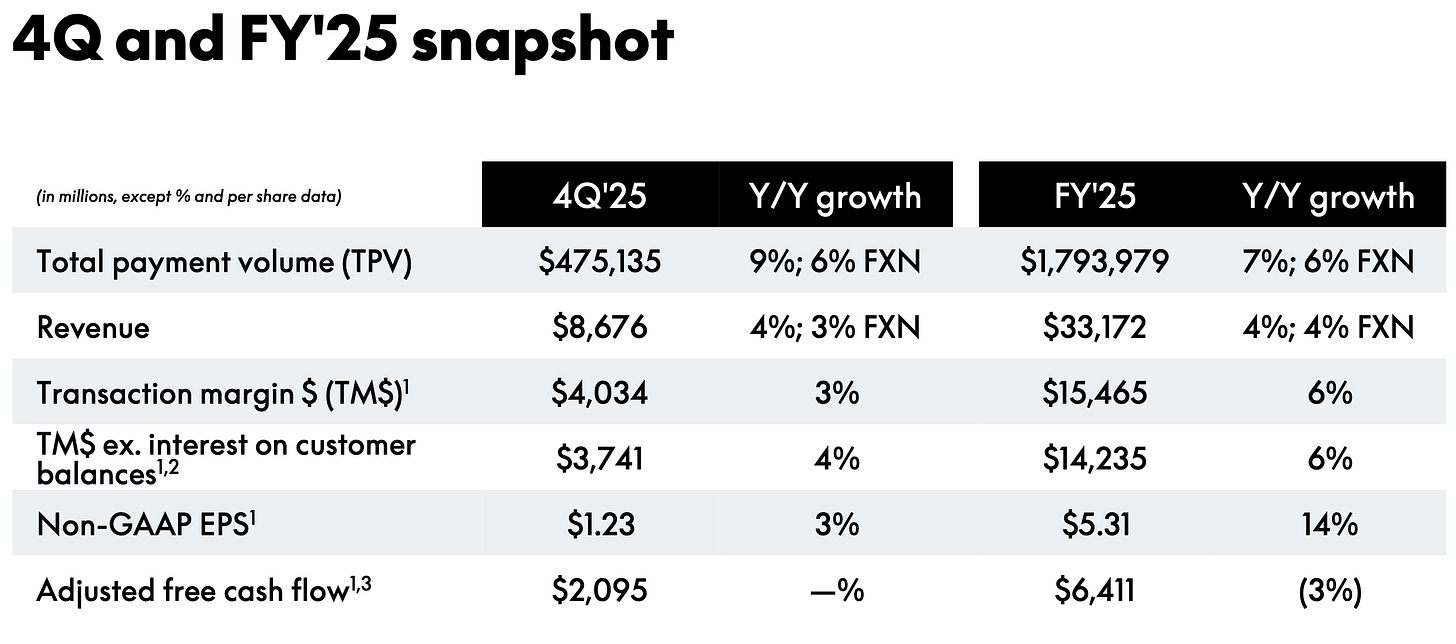

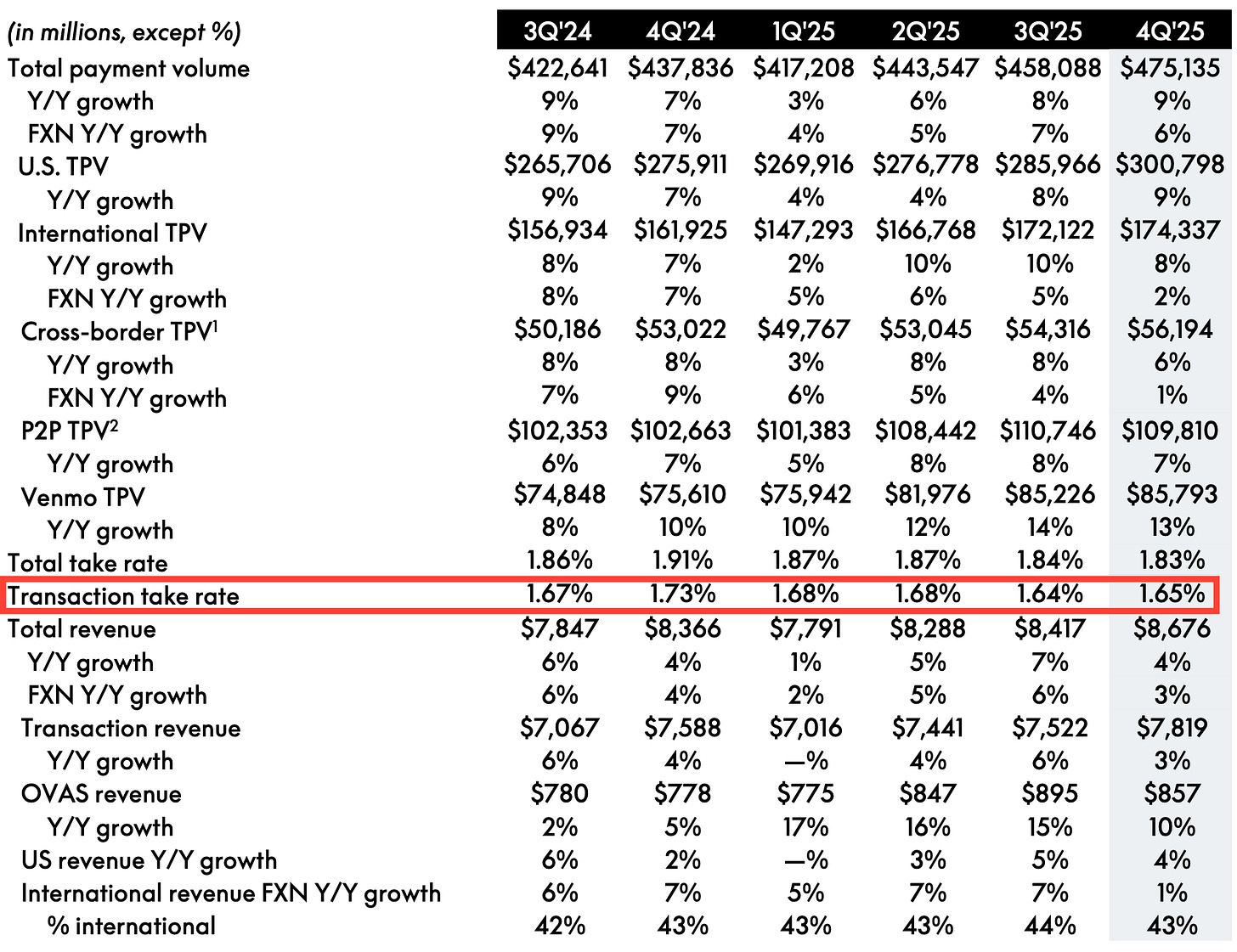

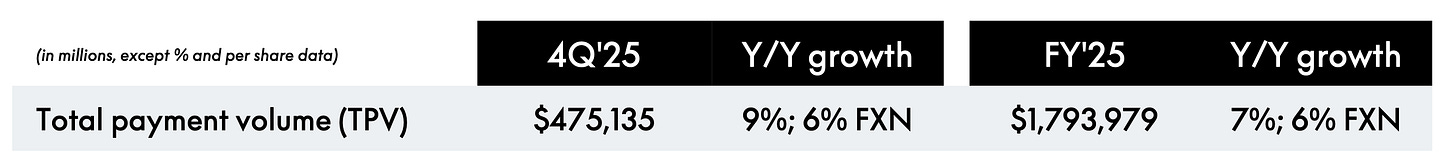

PayPal’s fourth quarter 2025 results confirmed my worst fears about the company’s direction. On the surface, the numbers might not seem catastrophic: net revenue was up about 4% y/y, and total payment volume (TPV; the total value of transactions processed) grew 9%. PayPal is still growing a little. The problem is that these growth rates are feeble, and they mask serious weakness in PayPal’s core business.

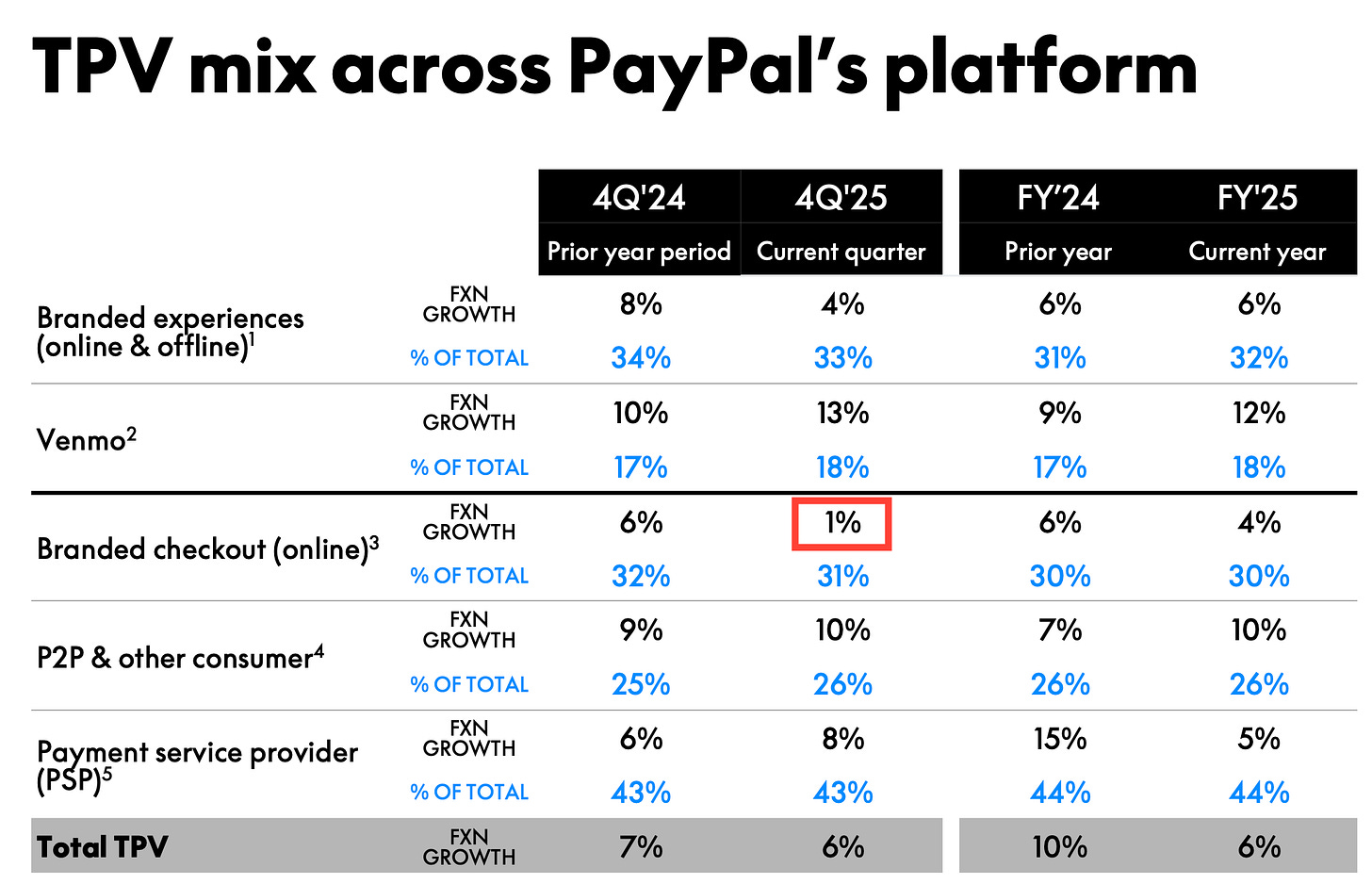

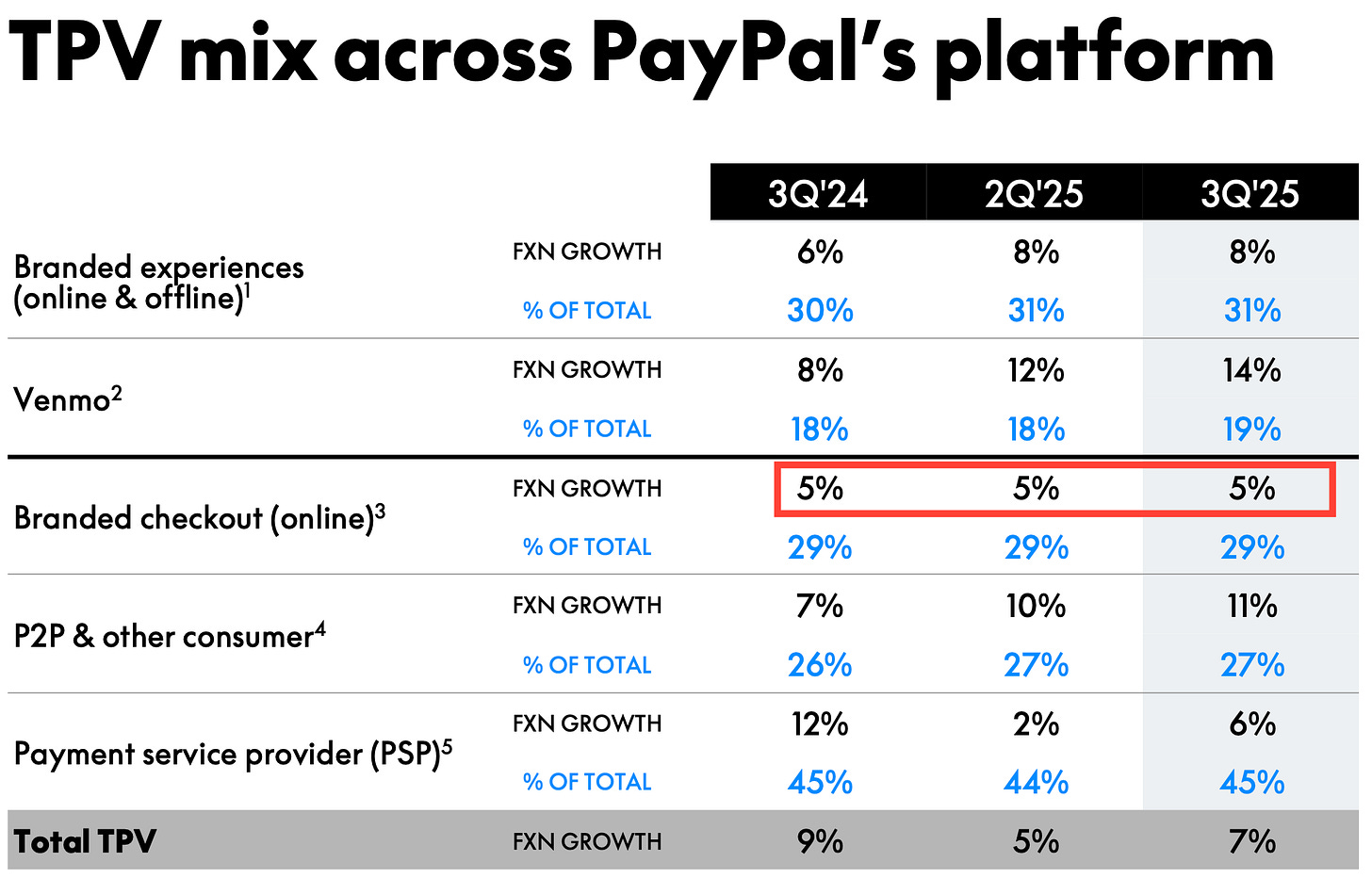

Branded checkout is barely treading water. This is the heart of PayPal’s business. When you use the PayPal button to pay online (or in an app) using your PayPal or Venmo wallet, that’s a branded checkout. In Q4, the volume of these online branded transactions grew only 1% from the prior year…yes 1%.

In the previous couple of quarters, it grew 5%, which was already nothing spectacular.

Now it nearly flatlined during the all-important holiday season. For context, e-commerce as a whole was growing faster than that (mid-single-digits or more, depending on the market). So PayPal lost market share in its flagship product. Fewer people (proportionally) chose to use the PayPal button at checkout. This is a huge red flag because branded checkout has historically been PayPal’s cash cow and key differentiator.

Management partly blamed macroeconomic issues. They said U.S. retail spending softened toward the end of the year and noted weakness in some international markets (Germany was specifically called out as a soft spot). They also pointed to a slowdown in certain high-growth merchant verticals.

Those factors certainly played a role. If shoppers are tightening their belts or shifting spending, PayPal feels it. However, it’s hard to ignore that competitors are encroaching too. Alternative payment options (from Apple Pay and Google Pay to Shopify’s Shop Pay and various “buy now, pay later” options) are grabbing mindshare. Many online retailers have also streamlined their own checkouts. The PayPal button doesn’t dominate the way it once did. In short, PayPal’s core online checkout business has stalled out, even in a quarter when it should have shined.

The Q4 results did have some bright spots, but they were not enough to save the story. PayPal’s other businesses grew faster than the core, as they have for a while:

Unbranded processing (PSP): This is PayPal’s service for big merchants where PayPal acts more like a behind-the-scenes credit card processor (through Braintree and other platforms). That volume grew about 8% in Q4, an acceleration from earlier in the year. Essentially, PayPal is doing more “plumbing” payments for merchants. This helped total TPV grow faster than the 1% branded figure. The downside: these unbranded transactions bring in lower fees per dollar than a PayPal-branded checkout, so they contribute less to revenue and profit for the same volume.

Venmo and newer experiences: Venmo’s payment volume was up 13% in Q4, marking five consecutive quarters of double-digit growth. More people are using Venmo to pay friends and increasingly to pay merchants. Venmo’s revenue (mostly from things like instant transfer fees and business payments) grew about 20% in 2025 to around $1.7 billion. It’s encouraging to see Venmo growing and contributing more. PayPal also noted that “Pay with Venmo” (using Venmo at PayPal merchant checkouts) and its Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) offerings grew very strongly (over 30% and 23% respectively in Q4). These are areas where PayPal is actually taking share from competitors. BNPL in particular processed over $40 billion of volume in 2025, up more than 20% y/y. So, clearly, there is consumer demand for these newer options.

Other services: PayPal’s credit business (lending to merchants and consumers, including BNPL loans) performed well, and losses on those were kept low. The company’s value-added services revenue (like interest on customer balances, partnerships, etc.) grew about 10% in the quarter. Additionally, PayPal’s cost control in transaction losses (fraud, chargebacks) showed improvement. All these contributed to profit holding up.

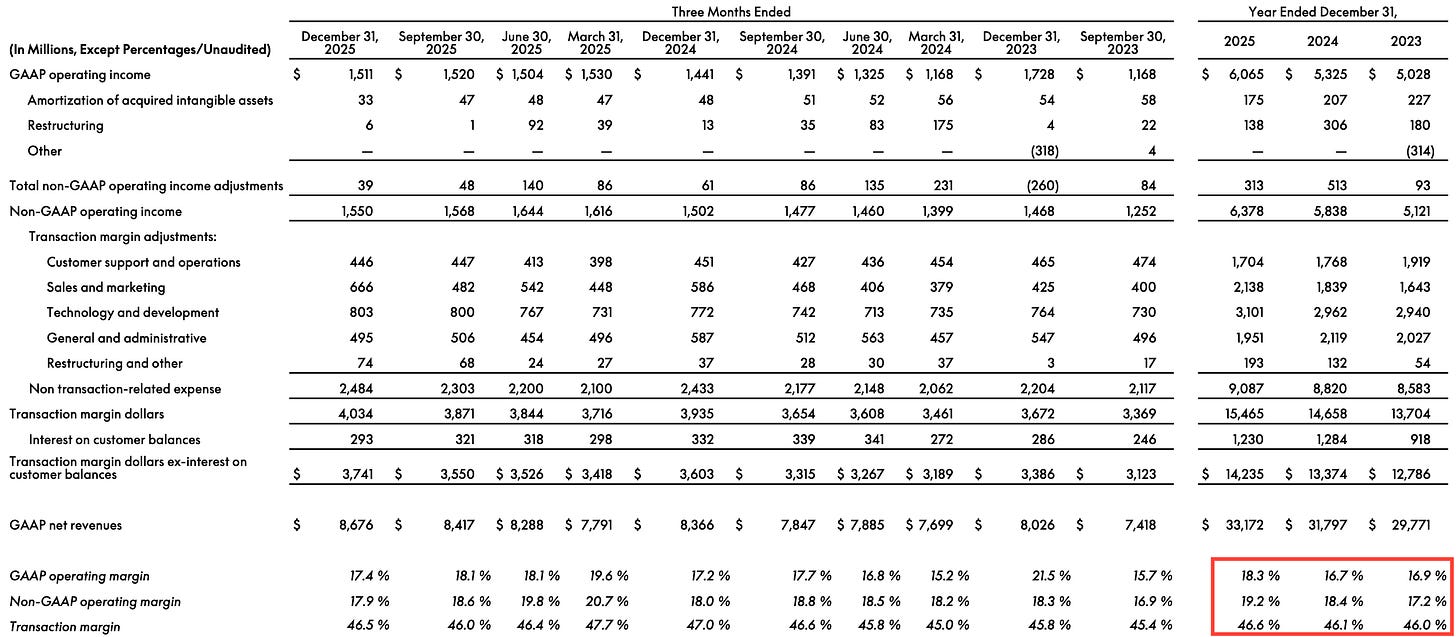

These positives show that PayPal is more than just its classic checkout button. The diversification helped offset the branded checkout slump to some degree. In fact, thanks to things like higher interest income, solid credit performance, and operational efficiencies, PayPal still eked out a 3% growth in non-GAAP operating income for Q4, and 9% growth for the full year 2025. EPS was up 3% for Q4 and 14% for the full year. So, 2025 wasn’t a financial disaster on paper. It was actually a year of modest growth and decent margin improvement.

So why the long face? Because the trajectory is going the wrong way. PayPal is only achieving those earnings gains by cutting costs and relying on side businesses, while the core engine sputters. The market cares about where the company is headed, and Q4 2025 signalled a concerning direction.

A few more key metrics paint the picture:

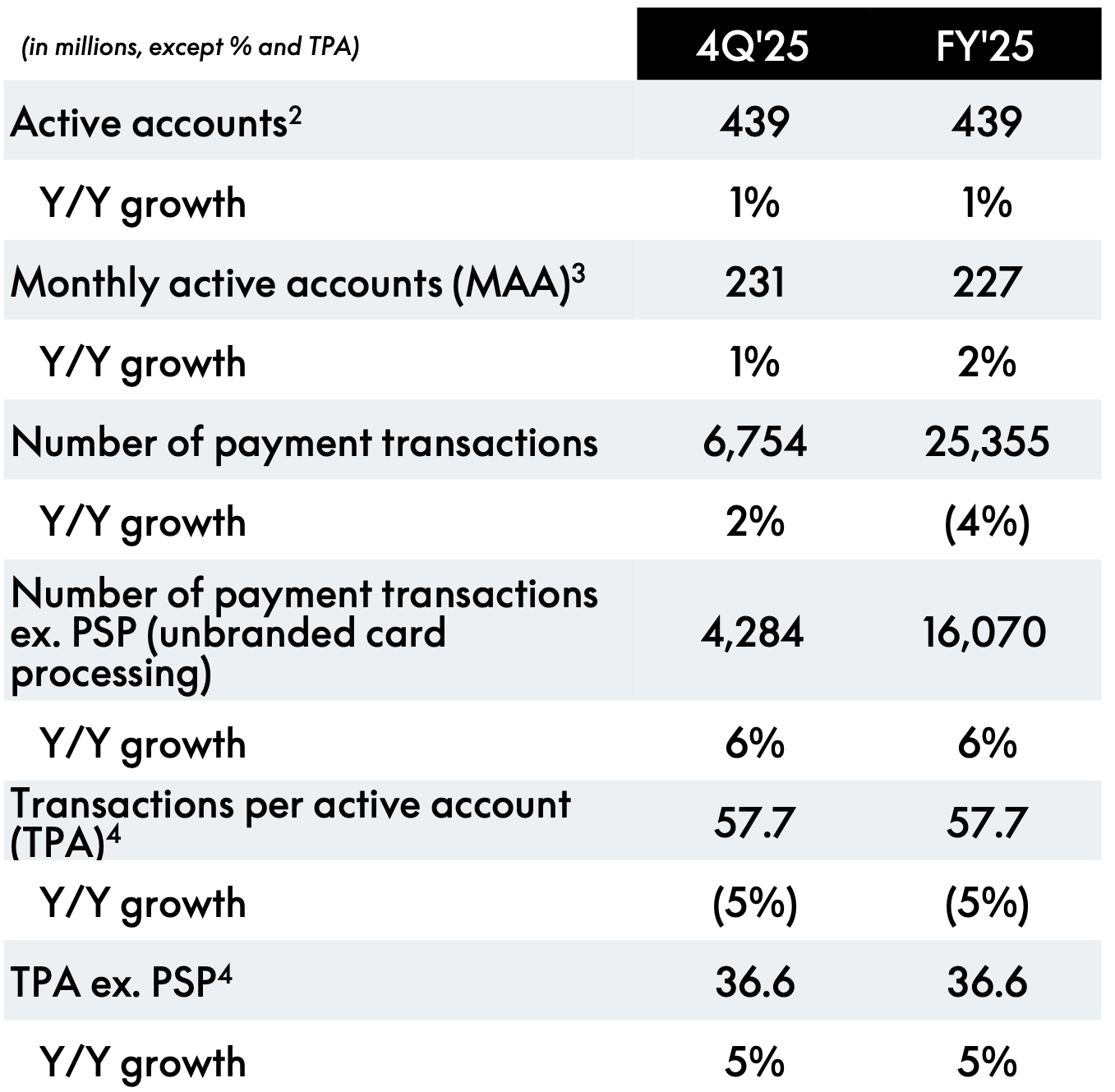

Active accounts barely grew.

PayPal ended 2025 with 439 million active accounts, up just 1% from a year prior. In the fourth quarter specifically, active accounts were almost flat.

Essentially, user growth has plateaued. This isn’t a new problem. Active user count stalled after the pandemic boom.

In fact, management previously admitted that many accounts they added in 2020-21 (through aggressive referral incentives and promotions) turned out to be inactive or low-value. They’ve since stopped chasing raw account growth for its own sake (those “give $10, get $10” signup promos), which is probably wise. But it means we can’t count on a rising user base to drive growth. PayPal has to make more money per user or re-energize usage among existing users.

Engagement dropped slightly.

One metric they track is transactions per active account (TPA), measured on a trailing 12-month basis. This basically tells how often the average account is being used. In Q4 2025, TPA was about 57.7 transactions per year, which was down 5% from the prior year.

So the typical user did a bit fewer PayPal transactions in 2025 than they did in 2024. Now, there is a nuance: if we exclude those new “PSP” merchant accounts (which might only be used for one specific integration), the TPA for regular users actually rose by 5%.

In other words, among true individual consumers, engagement is still rising modestly – people who use PayPal are using it a little more often on average. But the overall average fell because a lot of the “active accounts” aren’t as active (either one-and-done users or infrequent ones).

The key point remains: PayPal isn’t seeing a surge of activity per user that would offset the low user growth. The growth in usage is tepid.

Revenue lagged volume.

As mentioned, TPV grew 9%, but revenue only 4%. Part of this is currency fluctuations (on a currency-neutral basis, revenue was +3%, TPV +6%). But mostly it’s about mix and incentives.

PayPal’s take rate (the percentage of payment volume it captures as revenue) has been slipping. In Q4, the transaction take rate was 1.65%, down from 1.73% a year ago.

This decline is because more of the volume is coming from those lower-fee streams (like big merchant processing and certain partnerships), and because PayPal has been offering deals/ incentives to drive usage (for example, co-marketing with merchants to promote the PayPal button, which effectively shares some revenue back to merchants as rewards or discounts).

Basically, when a user pays $100 via PayPal, PayPal might have made $1.65 in revenue on average, whereas a year ago it made $1.73 on $100. That doesn’t sound like a huge difference, but at PayPal’s scale (nearly half a trillion dollars of volume in a quarter), it adds up. The shift signals competitive pressure. PayPal had to sweeten the pot to keep transactions flowing, and it’s relying more on lower-margin lines of business. This is not a great trend for a company that once enjoyed hefty margins on a captive user base.

All of the above set the stage for what management did next: reset expectations and change leadership. On the Q4 2025 earnings call, PayPal’s tone was markedly sober and pragmatic. The interim CEO and CFO, Jamie Miller, openly acknowledged that execution has fallen short. “Our execution has not been what it needs to be,” she said bluntly. This was a clear admission that, despite the company’s efforts in 2025, they weren’t delivering the results they wanted in key areas (especially branded checkout).

To address this, the board announced a CEO transition. They appointed Enrique Lores as the next President and CEO. Lores was actually PayPal’s Board Chair and is best known for his tenure as CEO of HP Inc. He has a reputation for operational discipline. The choice of an insider (board member) with a hardware background is interesting, but it signals that PayPal wants a leader laser-focused on execution and efficiency.

Jamie Miller, who served as interim chief, will remain as CFO/COO. On the call, she and the Investor Relations head emphasized that Lores has been deeply involved in shaping the current strategy as Board Chair. In other words, the strategy isn’t drastically changing; the hope is that new leadership will execute it better and faster. They didn’t want to spook anyone into thinking PayPal is about to pivot in some crazy new direction, and it’s more about doubling down on doing the important things right.

That said, there was a major shift in communication: PayPal withdrew its long-term outlook. They had previously given targets going out a couple of years (for example, at an Investor Day in 2024, they laid out some goals for 2027). Now they’re saying “we’re no longer committing to those; we’re only going to give one-year-at-a-time guidance for now.”

This is a notable retreat.

It essentially admits that the confidence they had in hitting those ambitious out-year targets is gone. They don’t want to be held to predictions that they might miss, especially given how quickly things are changing in their business. This was disappointing to hear as it suggests that even management isn’t sure when growth will inflect upward again.

The guidance for 2026 that they did provide was quite muted:

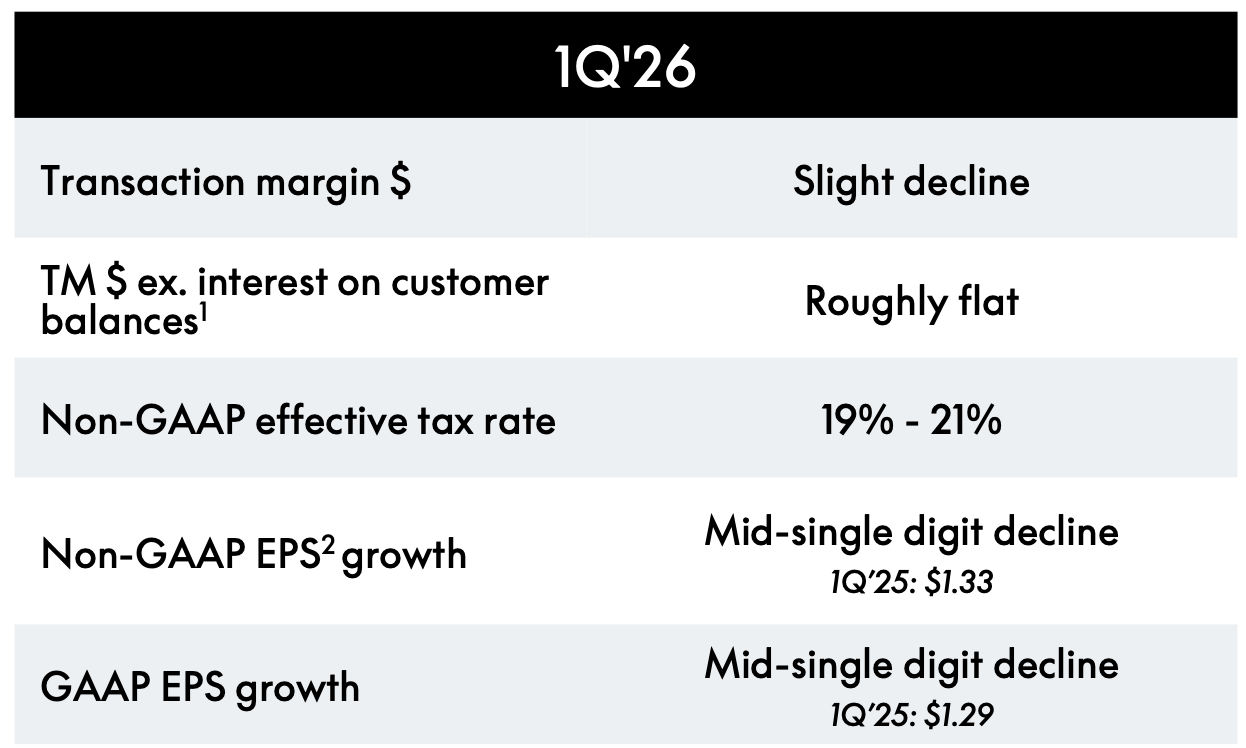

For Q1 2026, they expect revenue to grow in the low single digits and EPS to actually decline by mid-single-digits y/y. In other words, the first quarter of the new year will likely show a drop in profit compared to Q1 of last year.

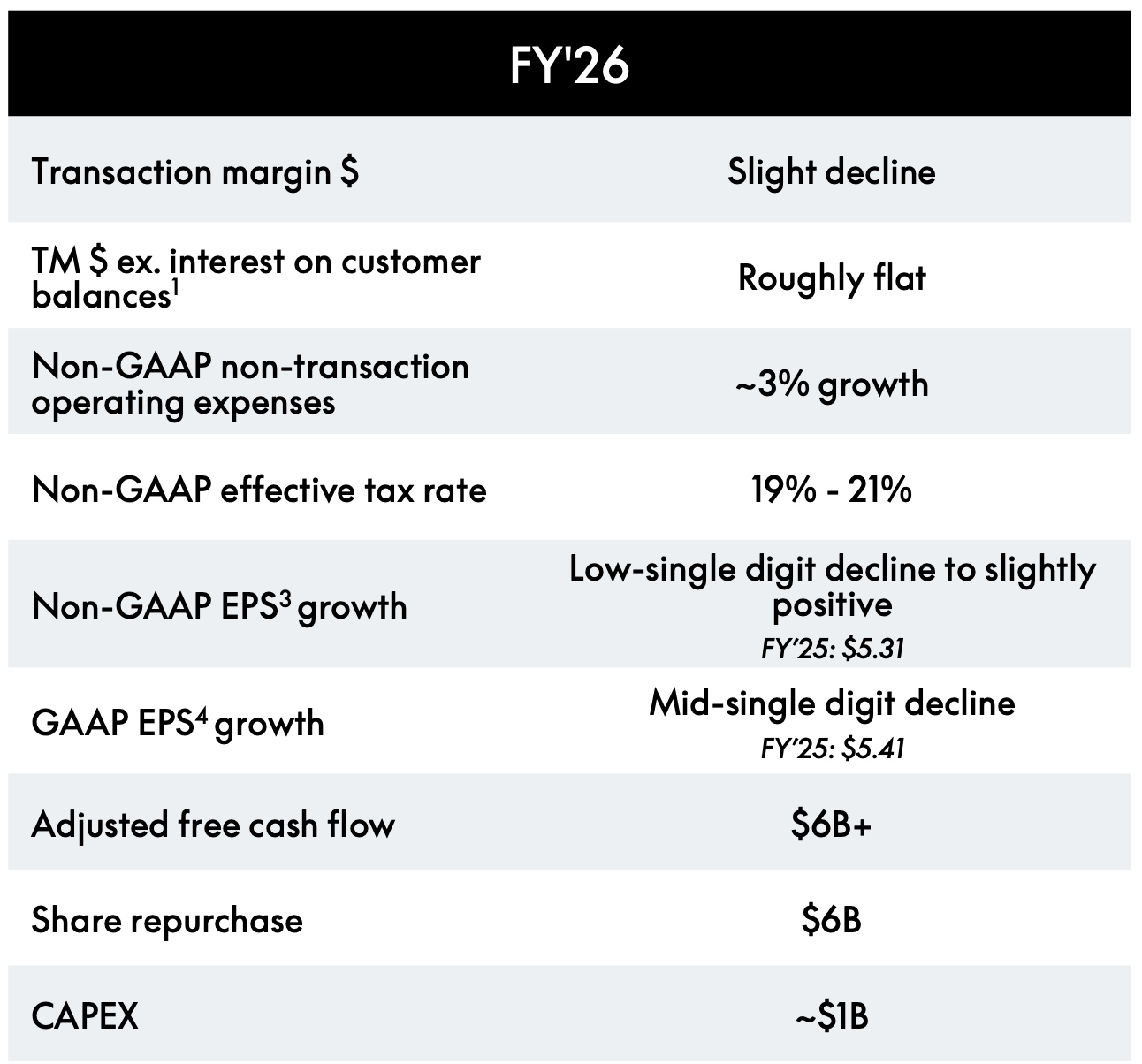

For full-year 2026, they forecast roughly flat transaction margin dollars (essentially flat operating profit from transactions) and non-transaction expenses up about 3%. Non-GAAP EPS could be anywhere from slightly down to slightly up for the year. The midpoint of their guide is basically zero earnings growth in 2026.

They do plan to continue significant share buybacks (another $6 billion worth in 2026, similar to 2025) and expect to generate at least $6 billion in free cash flow. They even initiated a small dividend in late 2025 (their first-ever dividend was $0.14 per share in Q4). These show that PayPal is financially stable enough to return cash to shareholders. But obviously, buybacks and dividends alone can’t drive the stock higher if the core business isn’t growing.

Put simply, 2026 is being framed as a “rebuilding year.” PayPal is going to invest more aggressively in areas to spark growth, which will weigh on short-term earnings. They mentioned that about 3 percentage points of growth in operating expense will be directed to “targeted growth investments”: things like product development, marketing, and incentives to boost engagement.

Two-thirds of those investments are aimed at fixing and rejuvenating branded checkout (and also expanding Buy Now Pay Later), with the rest going to other areas like Venmo, loyalty programs, and something they call “agentic commerce” (more on that buzzword in a second). These investments mean lower margins in the near term, but management believes they are crucial to get PayPal growing sustainably again.

On the call, Jamie Miller outlined three strategic priorities for branded checkout in 2026: experience, presentment, and selection.

Priority #1. Experience

Make using PayPal as easy and frictionless as possible for consumers. Remove any hassle at checkout. One big push here is biometric authentication and passkeys. Letting users log in with a fingerprint, face ID or a device key instead of passwords.

At the end of 2025, about 36% of PayPal’s consumers were what they call “checkout-ready,” meaning they have biometrics or a passkey set up, so they can pay with PayPal in one touch. That’s up from only 21% a year before. The goal is to get roughly half of customers checkout-ready by the end of 2026.

This matters because if paying with PayPal is super easy (no password typing, etc.), more people will choose it instead of pulling out a card. They’re also working on a “brand-new app” in 2026 to improve user experience and engagement, though details on that are scarce.

Priority #2. Presentment

Make sure the PayPal button is visible and enticing wherever people shop online. PayPal found that on some merchants’ sites, their button was hidden under extra menus or wasn’t offered at all in certain flows.

They are working closely with merchants to improve this placement. For example, integrating more directly into merchant checkouts or point-of-sale systems so that PayPal and Venmo are as prominent as possible.

They’re restructuring their sales teams to work more closely with high-impact merchants on these integration improvements. The idea is that if the PayPal option is front-and-center and works seamlessly, more shoppers will click it.

Priority #3. Selection (and loyalty)

Give users more reasons to choose PayPal. This includes things like rewards programs and other incentives. In 2026, they plan to roll out “PayPal Plus,” a new rewards/loyalty program in the U.S. and Europe. They want to offer perks (like cashback, merchant offers, or other benefits) to people who frequently use PayPal.

They’ve seen some success with a pilot loyalty program in other markets and want to expand on that. Also, by selection, they mean offering the right payment options to each user. Maybe a user wants to use their credit card through PayPal, or their bank account, or installment payments. PayPal wants to intelligently present the payment choice that the user is most likely to prefer, to increase conversion.

Essentially, make PayPal a hub that offers all the ways to pay (card, bank, BNPL, rewards, etc.) in one wallet, so the user has no reason to go elsewhere.

These initiatives sound sensible, but they will take time. Management admitted that they underestimated how involved this “checkout fix” would be. They’ve said they are maybe only 20% through the work needed to modernize PayPal’s checkout experience, and it could take a couple of years to fully roll out changes and see results.

That’s a tough pill to swallow, as it implies that branded checkout growth might remain sluggish for several more quarters. In fact, the 2026 guidance assumes only a “slightly positive to low-single-digit” growth in branded checkout volume for the full year. Basically, assuming it stays weak and only marginally improves by year-end. They are not forecasting a miraculous turnaround within 2026, just the groundwork for future improvement.

Agentic Commerce

Another concept thrown around was “agentic commerce.” This term refers to emerging AI-driven shopping experiences. Think of AI assistants or algorithms making purchases or recommendations on behalf of consumers. For example, an AI that automatically reorders your household items from the cheapest source, or voice assistants like Alexa, placing orders for you.

If this trend grows, the worry is that consumers won’t be manually clicking a PayPal button at checkout; the “agent” might handle transactions in the background using whatever payment method is default (which might bypass PayPal). PayPal is trying to stay ahead of this by being the payment method that those AI agents use.

Management mentioned they want PayPal to be a first mover in capturing these new flows. It’s pretty abstract at this point, but it shows they’re thinking about how shopping might change with AI. It’s good they’re aware of the threat, but it’s also a sign that traditional checkout could be disrupted even more in the future. This adds another layer of uncertainty to PayPal’s long-term outlook.

In the earnings call Q&A, analysts rightly pressed on a few key risks: the CEO change and whether a new chief means a new strategy (management said no, it’s about execution continuity); the timeline for these investments and when we might see payoff (they indicated improvements will start in late 2026 but it’s gradual, not a big bang); and whether PayPal could have done more, sooner, to avoid getting into this position (hindsight, yes, probably).

Analysts sounded skeptical about how quickly PayPal can right the ship. Management’s tone was cautiously optimistic but realistic, a noticeable shift from earlier in 2025 when they sounded more upbeat. This quarter, they acknowledged the shortcomings plainly (“our execution is just too slow” was a quote that stood out). They maintained that they are confident in their plan, but one could sense the pressure. It’s as if they were saying, “We know we’ve disappointed, but trust us, we have a plan and new leadership to get it done.”

From my perspective, Q4 2025 made it clear that the thesis for owning PayPal had fundamentally changed. The company isn’t on the trajectory I hoped it would be by now. Yes, they are taking steps to fix things, but those fixes will constrain profits in the near term and have uncertain outcomes. The core business is weaker than expected, and management effectively hit the reset button on long-term goals. All of that led me to exit the position.

Next, I want to reflect on my original investment thesis for PayPal and analyze what I got right and where I went wrong.

Reflecting on the Original Thesis

I was impressed by the company’s dominant position in online payments, its massive user base, and its strong cash flows.

PayPal had 432 million active users at the time, and was facilitating transactions worldwide. It was (and still is) a household name for digital payments.

The stock had been beaten down throughout 2022 and into 2023, falling from pandemic highs above $300 to around $90 as of early 2025.

In my view, the market had overreacted to short-term issues, and I saw the stock as deeply undervalued. I even did a discounted cash flow model that suggested a fair value around $140 per share.

In other words, I believed PYPL was trading at only 64% of its intrinsic value. I also saw several positive factors that I thought would drive the stock back up: margin expansion from cost cuts, continued growth (even if modest) in revenue, and PayPal’s entrenched role in a secular growth industry (digital payments).

Looking back now, some parts of that thesis proved accurate, but many did not. Here’s what I got right, and what I got wrong in my evaluation of PayPal:

What I Got Right:

#1. Margin expansion did happen (technically).

One of my core points was that PayPal’s business is highly scalable and has significant room to improve margins. I noted that as payment volumes grow, PayPal’s costs don’t rise proportionally, leading to operating leverage. I also talked about cost-cutting initiatives and the potential of AI and automation to streamline operations and reduce expenses (fraud prevention, customer service, etc.).

In 2025, PayPal did improve margins. GAAP operating margin rose to 18.3% from 16.7% in 2024. Non-GAAP operating margin rose to 19.2% from 18.4% (2024), itself up from the 2023 margin. Transaction margin also ticked up to 46.6% from 46.1%. Non-GAAP EPS grew 14% in 2025 while revenue grew 4%.

That means they squeezed more profit out of each dollar of sales, exactly the dynamic I anticipated. Management followed through on expense discipline (they had workforce reductions and other efficiency moves in 2023-2024), and it boosted the bottom line.

So in fairness, this part of my thesis was on target: PayPal’s cost structure is flexible, and they can expand earnings even with mild revenue growth. I expected mid-single-digit revenue growth and double-digit EPS growth, and that’s pretty much what they delivered for 2025.

#2. The secular trend is real: digital payments keep growing.

I argued that there’s a long runway for electronic payments globally, and cash is gradually declining. This macro tailwind remains intact. Global online payments volume hit record levels and continues to rise as more commerce moves online and as electronic payments penetrate everyday life (tapping your phone, sending money to friends, etc.).

PayPal, as a major player in this space, did benefit from that trend to some extent. Its total payment volumes did grow to a record $1.8 trillion in 2025.

So I was right that PayPal wasn’t about to shrink or lose relevance overnight; the pie is getting bigger. Where I was wrong was assuming PayPal would easily keep a healthy slice of that pie (more on competition in a moment).

#3. Venmo’s monetization remained challenging (which I expected).

In my original write-up, I specifically pointed out that Venmo, while extremely popular as an app, had uncertain profit potential. At that time, Venmo was growing rapidly in users and payment volume, but it wasn’t contributing much to profits.

I was wary of assuming Venmo could be a big earnings driver. This turned out to be wise skepticism. Even now, Venmo’s revenue is a small fraction of total PayPal revenue. And while Venmo grew revenue 20% to $1.7B in 2025, it’s still not hugely profitable in the grand scheme.

Peer-to-peer payments are low-margin (or free), and monetizing Venmo users through things like fees or merchant payments is a slow grind. So, I didn’t bake in unrealistic expectations for Venmo, and I’m glad I didn’t.

It’s a great service with lots of users (over 100 million active), but its impact on the bottom line remains limited. PayPal is still figuring out how to make Venmo as lucrative as its classic PayPal service.

That challenge continues, just as I anticipated.

#4. Competition was acknowledged… in theory.

I did note in my original piece that PayPal faces intense competition from all sides: traditional networks (Visa [V 0.00%↑], Mastercard [MA 0.00%↑]), tech giants (Apple [AAPL 0.00%↑], Google [GOOG 0.00%↑]), upstarts (Block/Square [XYZ 0.00%↑], Stripe), and others.

I discussed how mobile wallets and alternative payment methods were threatening PayPal’s turf. To my credit, I didn’t ignore the competitive landscape or assume PayPal had an unassailable moat. I recognized that growth would be “mid-single digits” partly because of this very competition. So I was not completely naive about the challenges.

Where I might claim a partial “right” is that I correctly identified key competitors and structural pressures on PayPal (like the blurring line between online and offline payments, and how big players like Apple Pay could eat into usage).

Those things did happen. For example, Apple Pay has continued to gain adoption for online checkout, and others like Shop Pay have become common on e-commerce sites. PayPal’s struggles in branded checkout are directly related to these competitive forces I foresaw.

What I Got Wrong:

#1. I overestimated PayPal’s ability to defend its leadership.

Yes, I noted competition, but I still fundamentally believed PayPal’s position as “the leader in online payments” would carry the day. In hindsight, I overestimated the strength and durability of PayPal’s moat.

I thought its two-sided network (millions of merchants and hundreds of millions of consumers) and strong brand trust would keep it growing solidly. This turned out to be too optimistic. Being the incumbent helped, but it did not guarantee continued success. Newer payment options proved very adept at eroding PayPal’s share.

For instance, many younger consumers now just use Cash App or Zelle for peer payments; many merchants promote their own payment apps or loyalty payment methods; and the overall fintech landscape moved fast. PayPal’s brand is still well-known, but it doesn’t have the same “must-have” cachet among users that it did a decade ago. I underestimated how quickly people might be willing to shift to other payment methods when given a slicker or more integrated option.

In short, I overestimated the moat. It’s a narrow one, as later analysis would suggest, not a wide one. There are fewer switching costs than I assumed. If Apple or Google makes it just as easy to pay, consumers don’t mind using those instead of PayPal.

#2. I bet on new leadership without seeing results.

When I wrote the original piece, PayPal had recently installed a new CEO (Alex Chriss, who took over in late 2023). I took that as a bullish sign. A fresh leader from outside (he came from Intuit) who could refocus the company. I spoke about PayPal “picking its innovation battles wisely” and the new CEO bringing renewed discipline after a big stock slump.

Unfortunately, that leadership change did not yield the kind of quick improvements I hoped for. By the end of 2025, PayPal’s board essentially said “we need an even bigger change” and replaced Chriss with Enrique Lores. That’s pretty striking. It means that in about two years, the first new CEO didn’t meet expectations.

So my optimism that a new captain would right the ship quickly was misplaced. The issues at PayPal turned out to be more entrenched, and maybe Chriss didn’t execute well or fast enough. Either way, leaning on the “new CEO” angle in my thesis was an error.

#3. Underestimating the depth of the growth problem.

I expected PayPal’s revenue growth to be modest (mid-single digits), and indeed it was. But where I was wrong was in assuming that was a temporary lull and that PayPal would find ways to accelerate a bit, or at least maintain that level easily.

Instead, growth nearly ground to a halt in the core business. I didn’t anticipate that something like branded checkout would flatline to 0-1% growth. I figured even with competition, PayPal could grow in the high single digits or so, given e-commerce tailwinds.

The reality is that PayPal’s growth problem was more severe than I thought. Part of it is macro (post-pandemic normalization), but part is self-inflicted (poor product evolution, slow rollouts, etc.). I also didn’t foresee that PayPal would have to invest even more just to try to get growth back. I thought by 2025 we’d be seeing the benefits of earlier investments like their refreshed app, their partnerships (e.g. with Amazon to allow Venmo, etc.), and things like PayPal’s “Fastlane” checkout. Instead, by late 2025, they were saying “we actually need to spend more in 2026 to fix things.”

So I clearly underestimated how much effort and time it would take for PayPal to reignite growth. My timeline was off; I was looking at a 12-18 month horizon for improvement, but it’s likely a multi-year challenge.

#4. Too much focus on cost and not enough on product.

This ties in with the growth point. My thesis was very centred on margins and cost efficiency (because that was something I could easily model and observe). I somewhat assumed the product side of the equation would take care of itself: that PayPal’s product was fundamentally strong and would remain a go-to for users.

This was a mistake.

The product/experience is exactly where PayPal faltered. Competitors built sleeker, faster checkouts; PayPal’s user interface and some policies lagged. For example, Apple Pay on an iPhone or Amazon’s one-click checkout on their site are extremely easy. PayPal has had friction (like password logins, less seamless integration on mobile apps, etc.). PayPal is now fixing those things, but I should have paid more attention to user experience and innovation pace.

This reminds me of KHC. They focused on cutting costs rather than investing in innovation.

In hindsight, it wasn’t just about cutting costs; it was about investing smartly to keep the service best-in-class. PayPal perhaps under-invested or mis-prioritized for a couple of years (they attempted various side ventures like crypto trading, stock trading within the app, etc., which didn’t move the needle).

I was wrong not to question whether PayPal was innovating fast enough to stay ahead. I took its competitive position for granted somewhat, and that was a blind spot.

#5. The reliance on external factors.

I didn’t fully account for how external trends might negatively impact PayPal. For instance, the rise of “agentic commerce” or AI-driven buying wasn’t on my radar. I wasn’t thinking about how the next wave of technology could bypass traditional checkout choices.

Also, regulatory or policy risks (like payment regulations or shifts in data privacy that could affect digital wallets) weren’t in my thesis, but are now a concern mentioned by others. These didn’t hit yet in a big way, but they lurk as issues that could further challenge the turnaround.

In essence, I may have been too narrow in my analysis, focusing on PayPal itself and its known competitors, but not on how the broader tech/payment ecosystem could evolve around it.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned and Looking Ahead

PayPal may very well surprise me in the coming years. If Enrique Lores can execute a successful turnaround, then PayPal’s stock could absolutely recover and even thrive.

The company still has enviable assets: hundreds of millions of users, deep integration with merchants, a trusted brand for handling money online, and healthy free cash flow. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where two or three years from now, PayPal has fixed its checkout flow, grown a bigger presence in in-store payments and high-growth areas like BNPL, and is once again growing revenues at, say, +10% with expanding margins.

In that scenario, the stock at today’s beaten-down price could multiply. There is a world where PayPal’s story turns very positive again, and that’s why I acknowledge it could become a multibagger if everything clicks.

However, investing is about probabilities and conviction. At this point, I don’t have high confidence in that rosy scenario. Instead, I see a long, uncertain road for PayPal to get its mojo back. The issues run deep: changing consumer habits, fierce competitors at every turn, and the company’s own execution track record hasn’t inspired confidence lately. The fact that they have to spend heavily just to drive low-single-digit growth in their main business is telling. It means the moat isn’t what it used to be; they can’t just sit back and watch the volumes roll in, and they have to fight for every transaction. That fight will take time and money, and success isn’t assured.

I now see PayPal as a speculative turnaround, not a core holding. And since I don’t speculate, I’m not holding PYPL. It may suit investors with patience and strong belief in new management, but it’s not something I can rely on with confidence. The decision became clear when I realized I wouldn’t buy it today if I didn’t already own it. So I cut the loss and moved on. Reallocating capital after reassessing the facts is simply part of the process.

The KHC parallell really lands. I've seen this pattern where cost-cutting becomes the default stragety when product innovation stalls. That 1% branded checkout growth during holiday quarter is the real warning sign - losing core market share while the category grows. The admission about being "20% through" modernization work is surprisingly candid. Most managment teams would never reveal that timeline publicly.