KT Deep Dive: A Telco Without an Edge and Why the Market’s Right About It

KT looks cheap on paper while having a dominant position in Korea’s telecom market but weak capital allocation, political interference, and no competitive edge explain why it stays cheap.

My wife and I got hooked on Korean series. When Squid Game dropped, we binged it in a couple of days. I like watching international shows because the culture leaks through the screen:

Venezuelan series run on high drama;

Nordic crime shows whisper in bleak tones;

Japanese workplace dramas live on ritual and hierarchy.

Korea’s stories, though, keep circling the same nerve: study hard, rank higher, be the best in class. One that really captures it is Crash Course in Romance on Netflix, a rom-com that somehow manages to turn a math tutoring academy into a high-stakes battlefield. In South Korea, professors and private tutors sit near the top of the food chain, a mirror opposite of North America where they often rank closer to underpaid idealists than celebrities. But that’s a discussion for another day… I’m diverging.

That cultural thread was top of mind when I started looking at South Korea’s telco market. I’ve spent my career around telecom; first as an investment analyst, then as head of corporate development for Chile’s largest telco. So a dirt-cheap stock in a stable three-player market gets my attention.

KT Corporation (KT 0.00%↑) fits that bill: it operates in South Korea’s oligopoly telecom market trading 5x forward earnings with a 4% dividend yield. In theory, that’s the kind of setup a telco investor dreams about: a solid dividend payer in an efficient market structure.

South Korea’s wireless sector has only three network operators (SK Telecom SKM 0.00%↑, KT, and LG Uplus) and has avoided destructive price wars in recent years. At first glance, KT’s modest valuation and benign competitive landscape made it look like a hidden gem.

However, my deeper analysis uncovered issues that cooled my enthusiasm. Despite some hidden value in its assets (KT even claims its real estate alone might be worth nearly KRW 15 trillion, roughly equal to its market cap), I found that KT suffers from poor capital allocation and lacks any real competitive edge.

The first lesson: rules of thumb can mislead. A #2 telco in a three-player market “should” earn ROIC above WACC. KT hasn’t. Years of sub-WACC returns and side quests tell a story of weak capital allocation and no moat.

The second lesson: culture and incentives shape outcomes. South Korea pushes hard to win; hagwons (cram schools), late-night study halls, and a college entrance exam day so serious flights are rerouted to keep things quiet. That intensity and competitive culture spills into telecom. In a market where three players could coast, they race eliminating any incremental profit pool in the market.

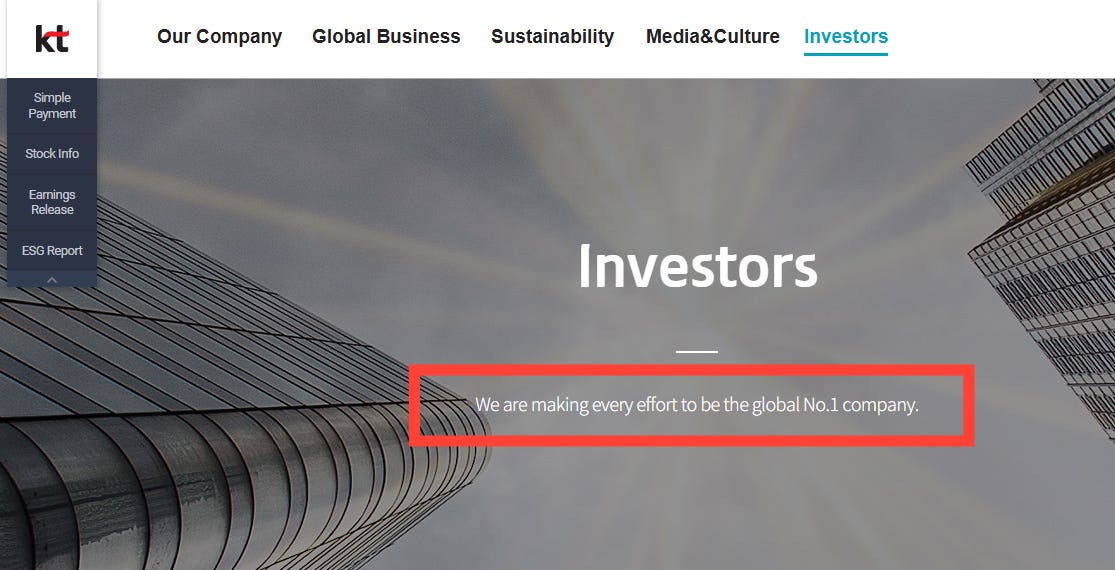

KT’s own site says it all: “We are making every effort to be the global No. 1 company.”

Not “No. 1 telco” nor “No. 1 Korean company” but No. 1 global company, period.

The ambition shows up in sprawling bets across AI, content, finance, and real estate. Ambition without edge spreads capital thin.

When I ran the numbers, the upside looked too limited and uncertain to justify an investment. I’m passing on KT, and in this write-up I’ll walk through the analysis and the why. Because, like Squid Game, when cooperation should create more value, the players still choose competition.

Table of Contents:

Elevator Pitch

KT Corporation is a cheap telecom stock on paper but it failed to earn a spot in the portfolio. The Korean telecom industry’s oligopoly structure hasn’t translated into high profits; all three carriers, including KT, have struggled with returns below their cost of capital.

KT’s core business is steady but lacks a clear growth catalyst or competitive moat. Management has pursued flashy ventures (AI, digital finance, media) and dealt with governance scandals, raising concerns about capital misallocation.

My valuation work (detailed below) found KT’s shares roughly around fair value ($19.3 per ADR vs. $18.8 market price) based on a DCF approach. But a sum-of-parts approach suggests a slightly higher base-case value of $24, still not enough upside to compensate for the risks.

Given regulatory pressures, an aging domestic market, questionable strategic bets, and no evident edge over rivals, I conclude that KT’s low valuation is justified.

Bottom line: KT offers a decent dividend, but without a margin of safety or a competitive advantage, it didn’t make it into the Beating the Tide stock picks.

Company History and Evolution

KT Corporation (originally Korea Telecom) has a long history as the country’s telecom incumbent. It began as a government-owned monopoly providing telephone services. In the 1990s, Korea liberalized telecom, and KT was listed on the stock market in 1998 as part of privatization.

The government fully gave up control by 2002, though it still exerts influence through regulators and state-linked investors. Interestingly, KT once ceded the mobile business entirely: in 1994 it spun off its wireless unit, which became SK Telecom, now KT’s biggest competitor.

Realizing the strategic mistake of abandoning mobile, KT re-entered the cellular market by creating a new mobile subsidiary in 1997. That mobile arm later merged back into KT, making KT today an integrated provider of fixed and mobile services.

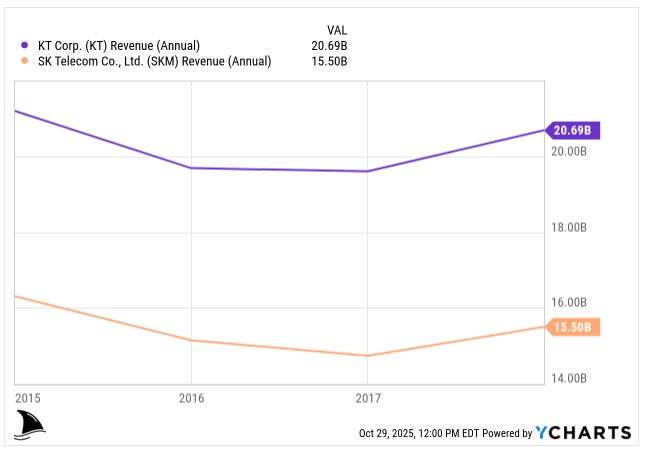

Over the past two decades, KT evolved from basic telephone and broadband into a diversified communications and IT services group. KT is Korea’s largest fixed-line and broadband operator… essentially the AT&T of South Korea.

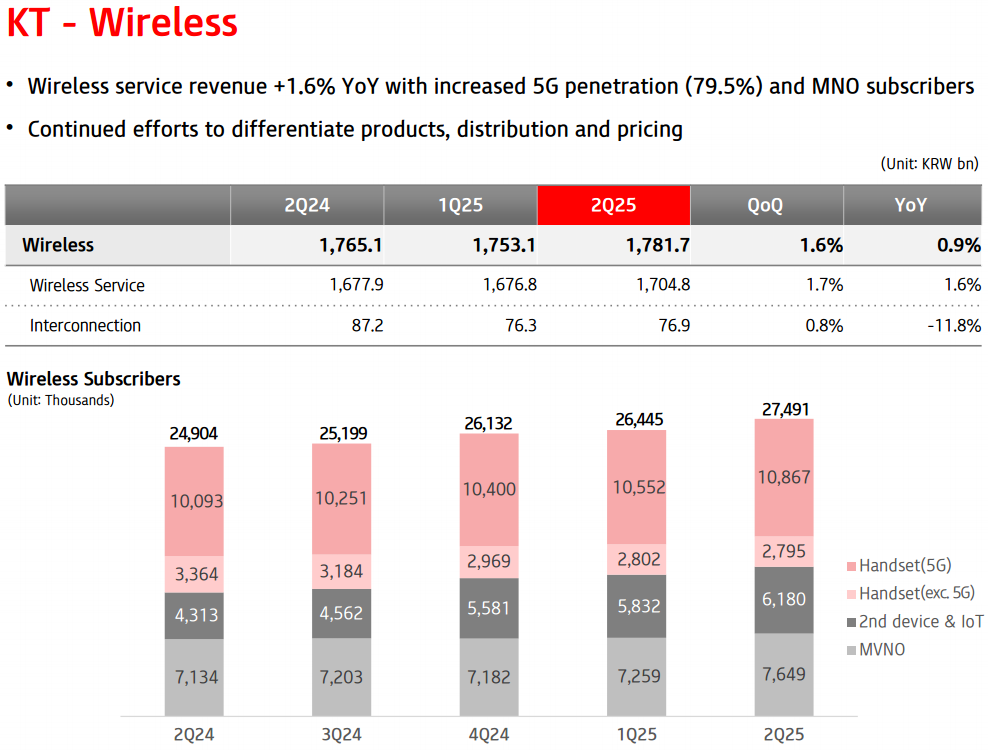

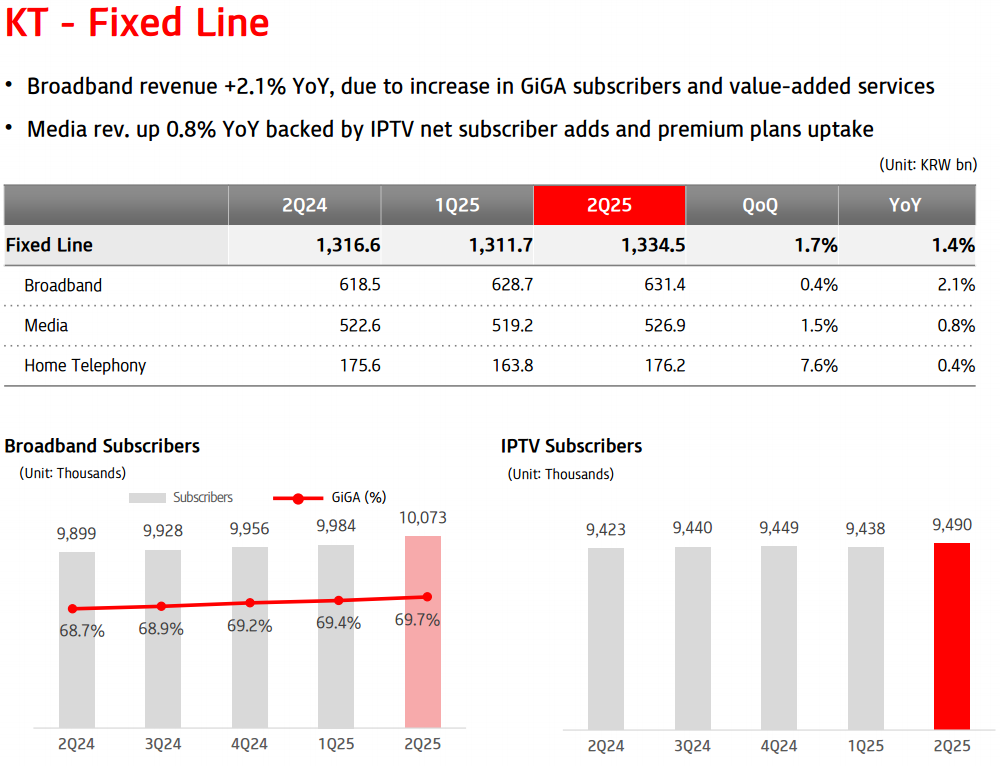

It still has about 11.5 million broadband internet customers and remains the backbone of the nation’s landline infrastructure. KT is also the #2 mobile carrier with around 26 million wireless subscribers (roughly a 30% market share).

Additionally, KT built up a pay-TV business: it runs both an IPTV service (with 9.4 million subscribers) and owns KT Skylife, a satellite TV broadcaster. In recent years KT has forayed into new areas like cloud data centers, AI services, fintech (it’s involved in an internet-only bank), and digital content production.

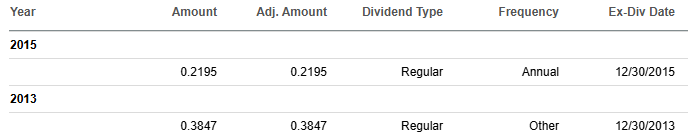

KT’s journey hasn’t been all smooth sailing. About a decade ago, the company hit a rough patch. It reported losses in 2013–2014 amid heavy competitive costs and one-off charges.

Even suspending its dividend in 2014. Under subsequent leadership, KT restructured and cut costs. By 2015 it restored the dividend, and by 2021 KT was back to a 50% payout ratio of profits.

Those cost-cutting years also saw KT sell off non-core assets and streamline operations.

For example, KT in 2014-2015 sold real estate and other assets, shoring up free cash flow. Profitability rebounded gradually thereafter. The company’s recent strategy (branded the “Corporate Value-Up Plan”) aims to boost ROE from about 6% in 2023 to 9–10% by 2028 by transforming KT into an AI-focused tech company and unlocking value from assets like real estate.

Business Model and Segments

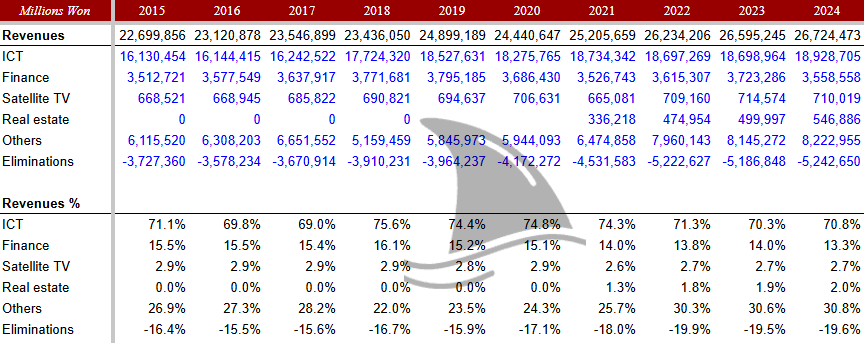

KT’s business model is built on a mix of traditional telecom services and newer ventures. The company breaks its revenue into four main segments:

ICT (Information & Communication Technology)

This is KT’s core telecom and IT services segment. It includes mobile wireless service, fixed-line telephone, broadband internet, and IPTV (digital TV over internet). It also encompasses newer ICT offerings like cloud computing, data center services, and AI solutions.

Essentially, all the communications services for consumers and businesses fall in this bucket. The ICT segment is by far the largest, accounting for about 71% of KT’s revenue. For example, in 2024, ICT brought in KRW 18.9 trillion of KT’s KRW 26.7 trillion in operating revenue.

These are the bread-and-butter services: phone plans, internet access, corporate network services, and so on. They tend to be stable, low-growth businesses with decent margins. KT’s wireless service is a major contributor; in Q2 2025, wireless revenue was KRW 1.78 trillion.

Broadband internet and IPTV are smaller but steady (broadband was KRW 631 billion in Q2 2025, growing 2% y/y, and IPTV/media was up 0.8% y/y).

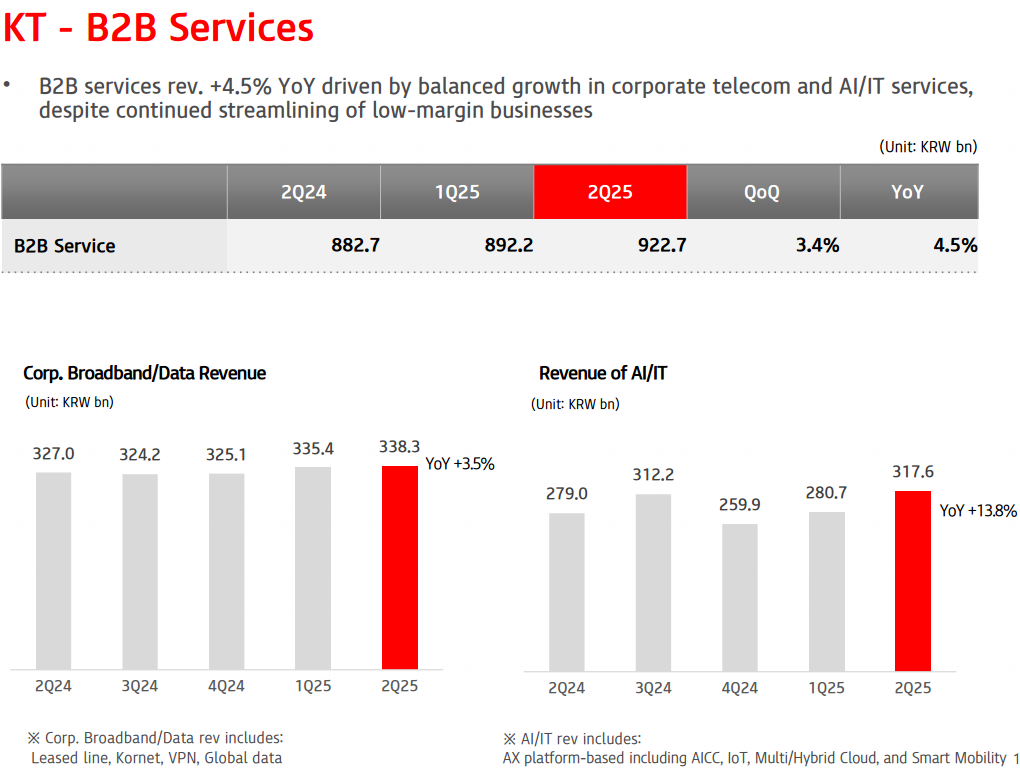

The ICT segment also includes B2B/enterprise services like cloud and AI solutions, which are growing quickly off a smaller base (KT’s AI/IT business revenue jumped 14% y/y in Q2 2025, and its data-center cloud subsidiary saw 23% growth).

In short, ICT is KT’s core connectivity business which is a fairly mature consumer telecom business but with pockets of growth in new tech services.

Finance

This segment is basically BC Card, a payment processing and credit card service company that KT controls. BC Card is one of South Korea’s major payment networks (similar to Visa/Mastercard domestically, and also a credit card issuer).

KT owns a majority stake and consolidates its results. The Finance segment provides about 13% of revenue. For instance, BC Card (and related fintech services) had KRW 910 billion revenue in Q2 2025 (actually down ~7% y/y amid slower consumer spending).

Its operating profit was roughly flat as the business managed risks and cut costs. While BC Card is a stable business, it’s lower-margin and faces heavy competition in payments. It also has an indirect stake in K-Bank, an internet-only bank (BC Card is the largest shareholder of K-Bank).

The Finance segment’s fortunes are tied to consumer spending levels and card transaction volumes in Korea… which are growing, but not high-growth. I view this segment as a non-core add-on; it provides diversification but not much of a competitive edge for KT (all the big telcos in Korea have some fintech play. For example, SK Telecom also has a stake in a major e-commerce/payments firm).

Satellite TV

This is the business of KT Skylife, the satellite broadcast subsidiary. Skylife offers direct-to-home satellite television. However, in an era of high-speed broadband and streaming, satellite TV is a declining segment.

This unit’s revenue is only 2.7% of KT’s total and is shrinking or flat. Skylife has struggled to grow as consumers shift to IPTV (including KT’s own Genie TV IPTV service) or online streaming.

By Q2 2025, KT’s “Media” revenues (which include IPTV) were growing slightly, but the satellite portion is essentially stagnant. I see Skylife’s stand-alone value to be minimal. It’s profitable in a small way (historically it paid some dividends). Its market capitalization is only around KRW 235 billion (~$165 million).

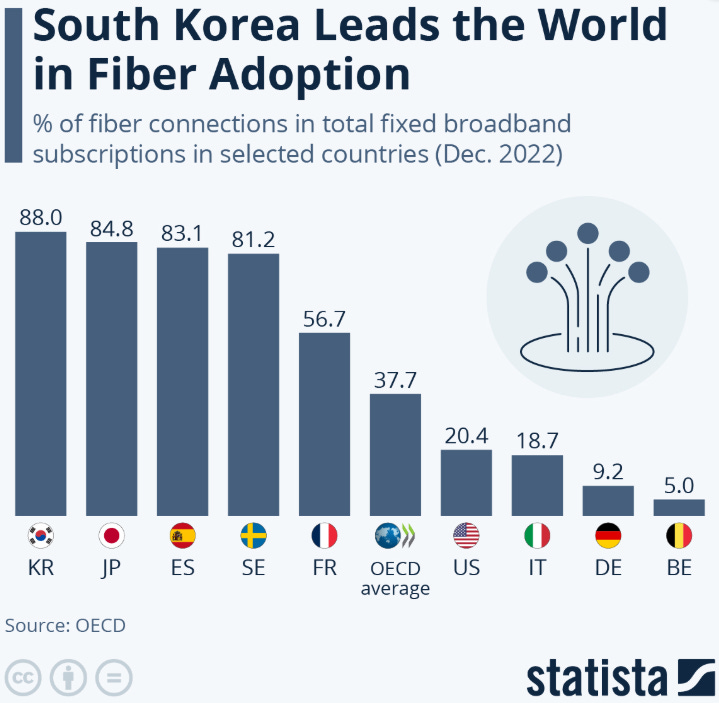

For a conglomerate like KT, that rounds to zero in terms of sum-of-parts impact. The writing is on the wall that satellite TV will keep diminishing as fiber broadband covers virtually all of Korea.

Real Estate

Over decades as the incumbent, KT accumulated lots of real estate: telephone exchange buildings, offices, cell tower sites, etc. In this segment (often reported as “Others” or “Real Estate”), KT owns, develops, or leases properties. The company actually has a dedicated subsidiary, KT Estate, which manages surplus properties and pursues development projects.

This segment is relatively small in revenue (just a few hundred million dollars annually), but it generated a noteworthy one-time gain in Q2 2025 when KT sold a property: KT’s real estate division contributed nearly KRW 0.4 trillion in one-off gains that quarter.

KT has stated that it is actively reviewing dozens of buildings for potential sale, highlighting past idle-asset disposals (e.g., the company reported KRW 270.5 billion cash-in from real-estate assets in Q2 2025). While there is no formal published estimate of full monetisation value, a Seeking Alpha article noted that KT indicated at a UBS conference that its real-estate holdings could be worth up to KRW 15 trillion (I couldn’t obtain the UBS presentation to verify).

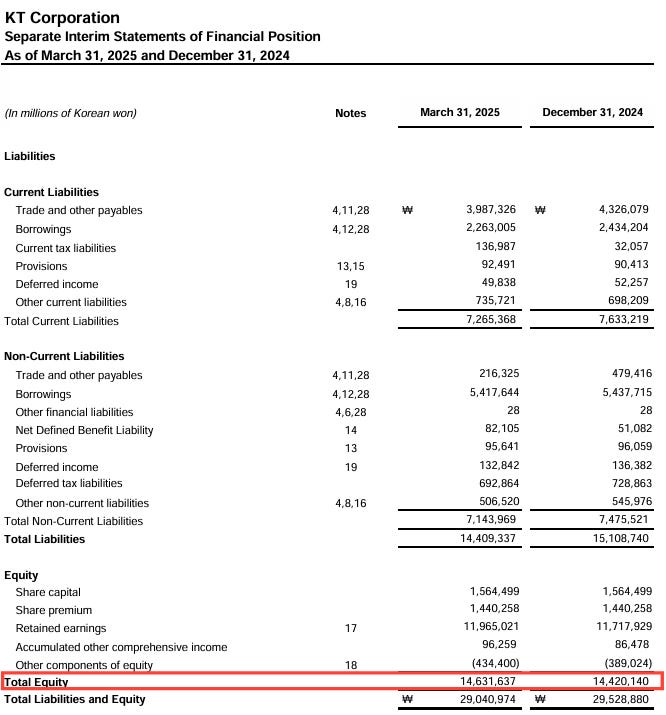

As of March 2025, KT’s book equity was KRW 14.6 trillion.

Thus, if the real-estate portfolio realised such a value, it would represent a multiple over book value and signal a meaningful upside in the asset base.

This suggests significant hidden asset value. However, unlocking it will be gradual. For now, I assign only a moderate value to real estate in my analysis (as not all properties can or should be sold at once). Still, KT’s real estate is an important “asset play” component of the stock story as selling just a portion above book value could unlock value and has indeed boosted profits recently.

Others

In addition to those main segments, KT has some other subsidiaries (collectively part of “Others”). These include content production companies like KT Studio Genie (which makes TV dramas and entertainment content) and Millie’s Library (an e-book subscription service). The content subsidiaries saw 6% revenue growth recently.

KT also has investments in tech startups (for instance, an AI chip startup called Rebellions, and others through venture funds). Most of these are small and don’t move the needle yet. The overall business model is thus a mix of utility-like telecom services (providing steady cash flows) and growth-oriented projects (AI, cloud, media) that aim to lift future profitability. KT’s strategy is to use the cash from its core telecom to invest in these new digital services, hoping to drive growth and raise its ROE.

The challenge for KT is that its core markets are mature. Wireless, broadband, and pay-TV are saturated in Korea, and growth is hard to come by without taking share from rivals or upselling new services.

That brings us to the industry context.

Why a three-player market hasn’t yielded fat profits?

Industry Analysis: Korea’s 3-Player Telecom Market

South Korea’s telecom industry is often cited as an ideal structure: only three major operators own nationwide networks, which should, in theory, behave rationally as an oligopoly.

Unlike some countries, Korea has no significant independent cable-TV operator grabbing broadband share, and past government attempts to introduce a fourth mobile carrier have repeatedly failed. The government has attempted this eight times.

On paper, this efficient scale should allow all three incumbents to earn healthy returns without fear of new entrants. Indeed, the Korean market has seen some rationalization: the dominant mobile player SK Telecom gradually let its market share slide below 50% (it’s 37% now due to the hacking incident) as the duopoly with KT made room for LG Uplus to grow.

And in recent years (circa 2019–2023), the three carriers have avoided all-out price wars, partly due to regulatory nudges to curb excessive marketing expenses. The government has periodically urged operators to limit handset subsidies and competition, aiming for stability in the market and consumer price relief.

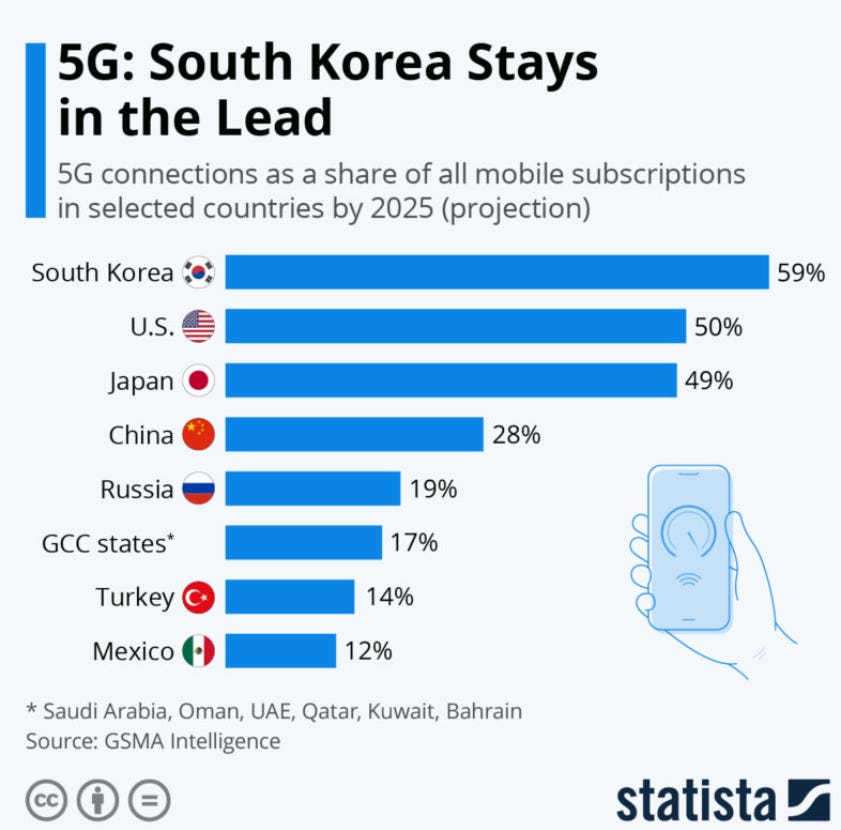

However, the reality is that competition, while not visible in price wars, has been intense in other ways. South Korea has among the world’s highest mobile data usage and early 5G adoption, which required huge capex by all carriers. They raced to roll out 5G networks and now are looking ahead to 6G.

This technological arms race is costly and has pressured returns. Meanwhile, promotional battles still happen. To poach each other’s customers, the operators often bundle services or give discounts, which eats into margins.

The telecom regulator also can be inconsistent: at times encouraging investment, but at other times enforcing price cuts. A vivid example was in 2017, when the government mandated lower mobile rates for customers not on phone subsidies, causing industry-wide revenue to dip.

So even in an oligopoly, policy can force a quasi-“price cut” to please consumers.

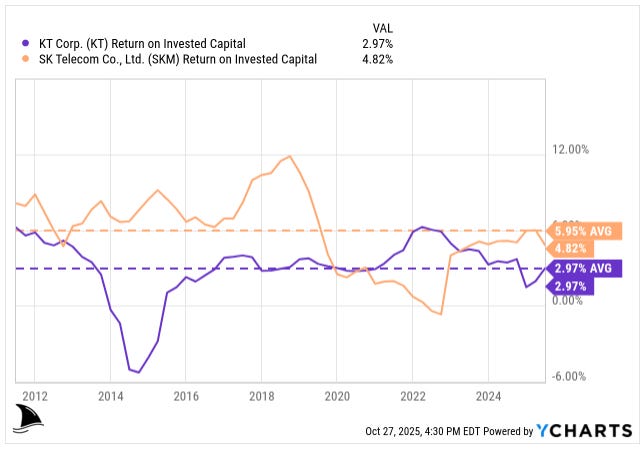

Importantly, all three Korean telcos have earned returns below their cost of capital for much of the past decade. Despite the stable market structure, their average ROIC has languished under the WACC.

This is quite surprising. In many countries, a big three oligopoly would churn out comfortable profits but the chart says it all. For more than a decade, KT’s ROIC has averaged just 3%, while SK Telecom’s hovers around 6%; both below their cost of capital (I estimated the cost of capital between 7% and 10%).

In a market with three entrenched players and no new entrants, you’d expect capital discipline and solid returns. Instead, Korea’s telcos have consistently deployed cash outside their competitive edge.

Rather than doubling down on areas where they hold clear structural advantages like network depth, enterprise relationships, and government contracts, they’ve ventured into businesses where they have little moat.

KT’s entered payments, real estate development, content production, and AI.

SK Telecom followed a similar path: investing in semiconductors, security, and platform ventures, only to spin many off into SK Square in 2021.

These moves reflect ambition but not focus. Every won reinvested in a non-core business drags down ROIC. For over a decade, returns have undershot WACC, meaning incremental growth has destroyed shareholder value, not created it.

Instead of milking the core telecom for cash, Korean telcos kept looking for the next big thing (e.g., e-commerce, media, AI, finance), investing heavily but not always profitably. This diversification has diluted the returns from the high-margin legacy telecom services.

For instance, SK Telecom spent $3 billions to buy into a semiconductor company (SK Hynix) in 2012 and has acquired various security and commerce businesses. KT, as we’ll discuss later, also spread into payments, cloud, etc. LG Uplus, the smallest player, by contrast stuck closer to its core wireless and broadband business with far fewer side ventures.

While, LG Uplus has steadily gained mobile market share over the past decade, creeping up by a few percentage points. Its ROIC is as bad as KT and SKM.

From a market share perspective, the landscape today is roughly: SK Telecom ~37%, KT ~31%, LG Uplus ~26% in mobile subscribers (SK Telecom and KT both also have low-cost brands and resellers, but those are the main shares). In fixed broadband, KT leads (being the incumbent with the most lines in apartment buildings), and HFC cable remains a minor player (LG Uplus acquired a cable-TV operator to bolster its broadband, and SK Telecom’s broadband arm SK Broadband has a solid presence too).

So each player has a stronghold: KT in fixed-line and enterprise connections, SKM in mobile, and LG as a scrappy integrated challenger.

The regulatory environment is a double-edged sword. The government likes having three stable telecom champions and often discourages a “race to the bottom” in pricing. But it also imposes consumer-friendly measures that limit profit.

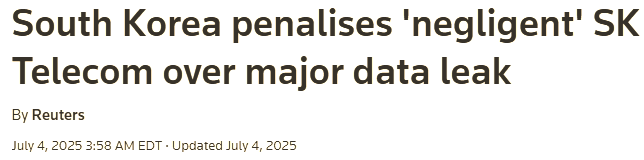

For example, the telecom regulator can set guidelines on fees and has forced operators to offer low-income or senior discounts. Also, Korea’s privacy watchdog didn’t hesitate to slap SK Telecom with a record KRW 134.8 billion fine in 2025 for a data breach, calling the company “negligent”.

So, operators face regulatory risk if they stumble in service quality or security.

One big theme is that South Korea’s telecom market is saturated and the population is aging. In South Korea there were 69–72 million mobile subscriptions versus a population of 51 million. Note the more subscriptions than people, underscoring the prevalence of multiple-device ownership.

Between 2020 and 2023, annual mobile subscriber growth slowed to about 0.7% per year. Essentially, everyone who wants a phone has one (or two). Broadband internet is similarly maxed out, with over 96% of households connected, and 88% on fiber lines.

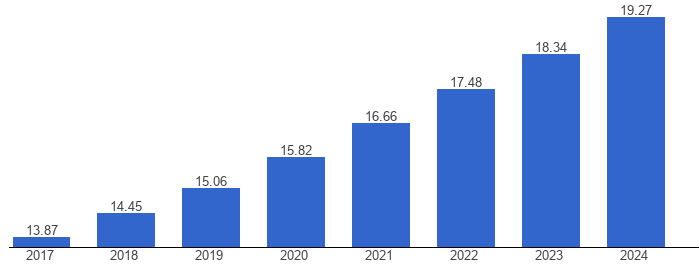

It’s hard to grow by adding new customers; instead, growth must come from selling new services (like 5G upgrades, unlimited data plans, or streaming content packages) to an existing base. Complicating this is demographics: South Korea is one of the fastest-aging societies. As of 2024, about 19.3% of Koreans were 65 or older.

The country is projected to surpass 20% by 2025, and rise significantly thereafter. Older consumers use less data on average and are slower to adopt pricey new technologies. For example, among younger adults smartphone penetration is essentially universal (near 100% for ages 18-39). Among seniors (+60 yrs), penetration lags in the ~80% range. And the country’s birth rate hit an astonishing low of 0.72 in 2023 meaning the future pool of young, tech-hungry customers is shrinking.

For telecom companies, an aging user base means lower growth potential in high-end mobile services and a need to tailor offerings (like senior-friendly plans or health-monitoring apps).

What about the elusive “4th operator”? The government has tried eight times to license a new mobile carrier to spur competition, but each attempt flopped. The most recent case was a consortium called Stage X. It won a bid in Jan 2024 to use some 5G spectrum reserved for a new entrant, but by mid-2024 the government revoked Stage X’s license after the company failed to raise the required capital (KRW 205 billion) and meet rollout requirements.

In fact, Stage X was the eighth attempt and its failure underscores how hard it is for a newcomer to break into this market. The existing three are so entrenched with massive network infrastructure and customer bases that a new carrier can’t easily justify the investment. So while authorities occasionally talk about “finding a catfish to stir up the big three,” as of now a fourth operator isn’t on the horizon. This is good for preventing a price war.

Competitor Landscape: Does KT Have an Edge?

On paper, KT should be very formidable: it’s the legacy incumbent with the largest fixed-network and a strong brand. It provides a full bundle of services, similar to what AT&T (T 0.00%↑) or Verizon (VZ 0.00%↑) do in the US.

Unfortunately, KT doesn’t really outshine its competitors in any critical area. If anything, SK Telecom has the prestige of being #1 in mobile and is often seen as the telecom technology leader in Korea, while LG Uplus has carved out a niche as an efficient, value-focused challenger.

SK Telecom

The largest mobile operator, historically had >50% market share (dating back to when it was a spin-off from KT in the ’90s). SKM has about 30 million mobile customers. It also owns a big chunk of the pay-TV and broadband market via its subsidiary SK Broadband.

SKM’s strategy has been to leverage its scale to invest in new tech. It poured money into areas like semiconductors (SK Hynix), security (ADT Caps), and even biotech and ride-hailing through its venture arm. It also built a metaverse platform (ifland) and an AI speaker business.

These diversification moves have met mixed success. Some, like Hynix, turned out to be brilliant (Hynix stock soared, benefiting SKM), some flopped like ifland (which was killed in 2024), but they also mean SKM’s attention isn’t solely on core telecom.

In terms of network, SKM is often perceived to have the best mobile network quality (it was first in deploying 5G). However, the gap is not huge; Korea’s telecom infrastructure is excellent across all providers. One could argue SKM has a slight edge in brand and maybe the highest-paying customer segment. But SKT’s expansive investments have also diluted its returns, similar to KT.

KT Corporation (Our subject)

Second in mobile, first in broadband, also a leader in enterprise telecom. KT’s “edge,” historically, is its broad range of services and its relationship with government/public sector projects (being the former state telco, it often gets large contracts for government communications, though that’s not exclusive).

KT also has the advantage of its fixed-line infrastructure. For example, it can offer bundled packages (mobile + internet + IPTV) and have a slight cost advantage on delivering broadband since it already has lines to most buildings. But in practice, LG Uplus and SK Broadband have caught up through their own fiber deployments and local loop unbundling. So KT’s broadband share, while #1, hasn’t given it pricing power; broadband prices are low and competitive.

Crucially, nothing KT offers is truly differentiated from what SKM or LGU can offer. All three have 5G networks, all offer unlimited data plans, all have similar pricing tiers due to competition or regulation. KT’s IPTV has exclusive content, but so do SKT’s and LG’s TV services.

KT’s mobile market share has not significantly grown at the expense of others; in fact, LGU has been the one slowly inching up share, largely at the expense of SKT’s legacy dominance.

LG Uplus

The smallest, but arguably the leanest. LGU is part of the LG conglomerate and entered mobile later, but it has been very aggressive in marketing and slightly undercutting on price.

LGU has far fewer side businesses outside telecom. It is focused on improving its network and customer service, which might be why its returns are on par with the others despite less scale. LGU also benefitted from number portability rules that allow customers to easily switch carriers; many cost-conscious users eventually try LGU if it offers a better deal.

Over +10 years, LGU grew from a minor player to 25% share. One might say LGU’s edge was being hungry and focused, picking up niche opportunities (like offering unlimited data at cheaper rates earlier, or bundling with LG Electronics devices). Still, LGU is not wildly more profitable.

So where does that leave KT? In truth, none of the three has a durable competitive advantage over the others in the traditional telco business. Telecom services can have high barriers to entry (due to massive network cost), but when three equally resourced players would rather compete than coexist, it turns into a slugfest.

There’s a concept of efficient scale that a three-player market should deter new entrants and allow healthy profits. But Korea’s case shows that efficient scale doesn’t guarantee high margins if the existing competitors keep undercutting each other or overspending on new ventures.

One example: in 2019, the government reduced mobile number portability wait times (making it easier to switch carriers fast), and companies engaged in covert discounting to poach customers. The result was churn and lower ARPU.

Between 2020 and 2023, industry ARPU actually declined ~6.8% despite the introduction of premium-priced 5G services. That indicates how competitive dynamics or regulatory pressures forced pricing down. Also, roughly one-third of customers switching in 3 years shows how brand loyalty is limited. Consumers will jump to another carrier for a better deal or promotion.

KT’s best shot at an edge might be its enterprise and government business. KT has long provided telecommunications for government agencies, public safety networks, and enterprise leased lines. With the push into AI and cloud, KT is positioning as an “AI partner” for big companies and local governments. For instance, KT built AI-powered call center solutions (so-called AI contact centers) and is aiming for KRW 1 trillion in AI-related sales within two years.

KT launched its own large language model (Mi:dm 2.0) and partnered with Microsoft and Palantir to enhance AI offerings. These moves are interesting, KT is basically trying to leverage its telecom infrastructure (like data centers and networks) to offer digital transformation services.

If KT can become the go-to cloud and AI provider domestically, that could differentiate it from SKM and LGU (which are also doing AI, but KT is arguably pushing hardest on this front).

That said, it’s far from certain that telecom-based AI initiatives will create a moat. Other countries’ telcos have tried to become tech players with limited success. Telecom management teams often lack the agility of pure tech firms, and they risk burning capital on R&D without clear payoff. We’ll discuss this more in the risks section (generative AI investment). For now, suffice it to say KT’s “edge” in AI is unproven, it’s more of a strategy than an advantage.

In the consumer market, KT doesn’t have a pricing edge (all carriers’ plans are within a narrow range after regulations). Network-wise, KT’s mobile network is excellent, but SKM usually ranks slightly higher in coverage and speed in independent tests. KT’s broadband is top-notch, yet LG and SKB offer similar fiber plans.

In content, KT’s IPTV has original shows via Studio Genie, but SKM has its own production with Studio Wavve, and LGUplus partners with various streaming services. It’s an arms race where each is matching the other’s moves.

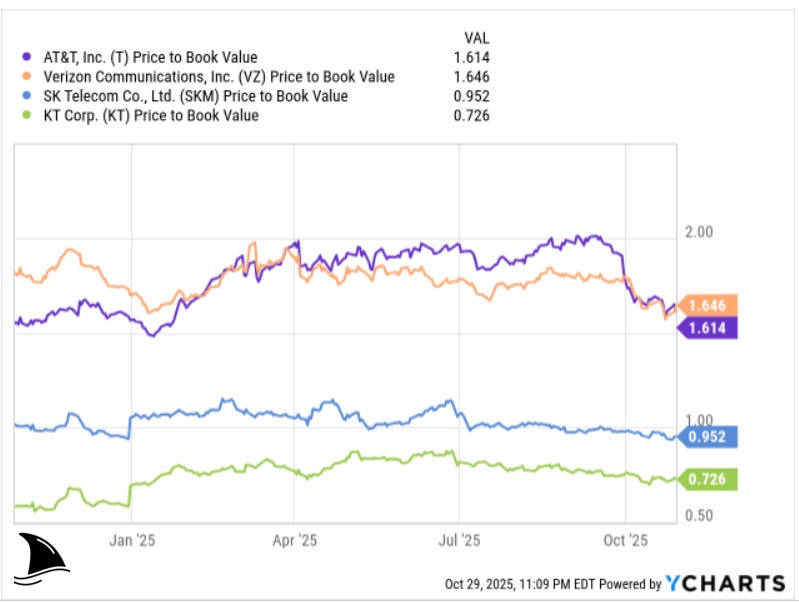

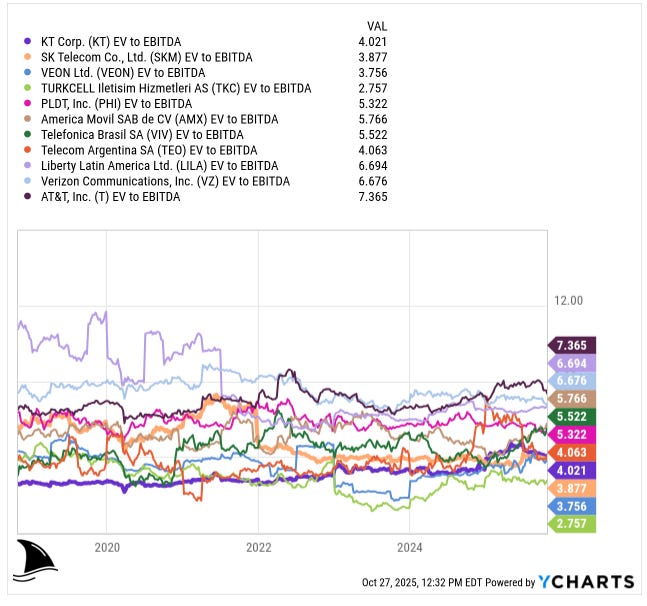

Indeed, despite one of the world’s most advanced telecom markets, KT and SKM trade at just 45%–55% of the price-to-book multiples of U.S. telecom peers.

That’s the market signaling that these companies don’t have high-return opportunities. They’re valued more like utilities than tech growth stories.

Management and Governance

KT’s management and governance have been, frankly, a bit messy. The company has churned through CEOs and been entangled in political interference and corruption scandals, which is not what I want to see.

Leadership Turnover

KT was led for most of the late 2010s by CEO Hwang Chang-gyu (2014–2018), followed by Ku Hyeon-mo (2019–2023). Ku Hyeon-mo, a long-time KT insider, was CEO until early 2023. When his first term was ending, KT’s board initially moved to reappoint him. However, that process triggered a backlash (more on that shortly) and ultimately failed. Ku resigned under pressure in March 2023, leaving KT without a permanent CEO for months.

An interim CEO (Park Jong-wook) took over day-to-day operations, but major decisions were put on hold. In August 2023, KT finally appointed a new CEO from outside the company: Young-Shub Kim. Kim Young-shub is a former CEO of LG CNS (an IT services arm of LG) and a seasoned executive in digital transformation projects. He was seen as an outsider with tech experience and no baggage from KT’s internal factions. His term was set for 3 years (through 2026).

Kim’s appointment ended a months-long leadership vacuum at KT. It was a relief to see a stable leader in place again. Under Kim Young-shub’s brief tenure so far, KT’s financial performance actually improved.

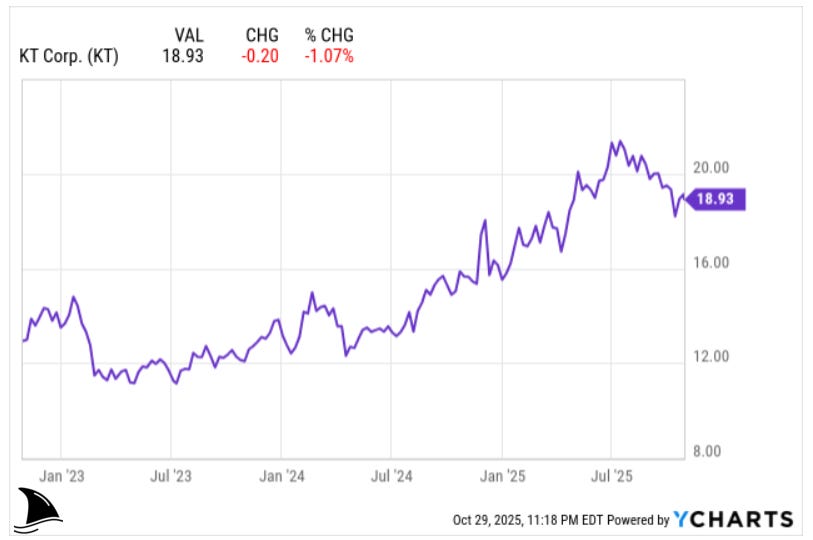

In H1 2025, KT delivered strong profit growth (Q1 2025 operating profit rose 36% y/y, and Q2 2025 op profit more than doubled y/y). The ADS price also climbed from around $12 to over $20.

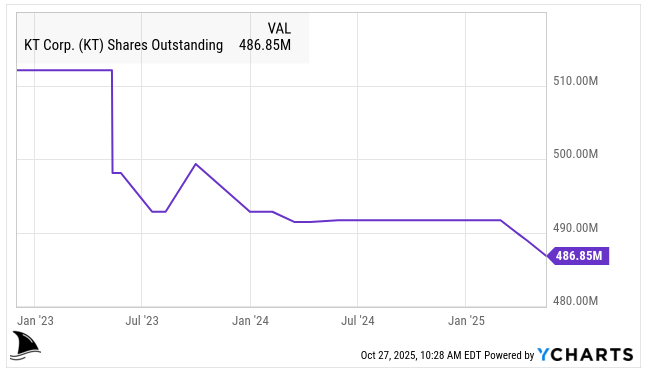

This suggests that despite the noise, the business has been chugging along, and investors responded positively to moves like share buybacks and higher dividends (KT initiated a KRW 250 billion buyback in 2025 and raised its quarterly dividend 20% y/y to KRW 600/share). Kim Young-shub has emphasized making KT a “digital platform company” and continuing the AI investments.

Political Meddling

One of KT’s governance quirks is that, even after privatization, its CEO selection often draws government scrutiny. The South Korean government, through entities like the National Pension Service (NPS), has been an influential stakeholder.

In early 2023, the conservative administration under President Yoon Suk-yeol effectively blocked KT’s board from reappointing CEO Ku Hyeon-mo, citing concerns over the nomination process and ongoing investigations.

The NPS (which was KT’s largest shareholder at the time) voted against Ku, and politicians from the ruling party pressured KT, mentioning past issues on Ku’s watch. There was also an attempt to install Yun Kyung-lim (head of KT’s transformation unit) as CEO, but that too was thwarted amid accusations he was a close ally of Ku. Opposition lawmakers criticized the government for interfering in what is technically a private company, but the reality is KT has a quasi-public status in the eyes of officials. This has led to a kind of tug-of-war: one government tries to oust certain managers, another might favor them.

Fast forward to 2025: South Korea saw a change in political power with a new president (Lee Jae-myung, a different party) taking office. Now questions are arising if the new government will in turn pressure KT’s current CEO Kim Young-shub to step down, since he is perceived by some as having been the previous administration’s pick. KT’s unions even accused Kim of cozying up to the former President Yoon by hiring ex-prosecutors into KT management.

This sounds very political, and it is. The core issue is KT is seen as a strategic company, and both government and opposition want to have a say in its direction. There’s hope that with NPS now a smaller shareholder (Hyundai Motor Group became the largest shareholder, as NPS sold down to second place), government influence might wane. But it’s clear that CEO turnover at KT has often been politicized. For us, this means uncertainty. You don’t know if a CEO will serve their full term or get swept out by political tides. Frequent leadership changes also impede long-term strategy.

Corruption Scandals

Unfortunately, KT has a history of high-profile scandals. In 2021, allegations emerged of slush funds and bribery involving KT’s management. This led to investigations in Korea and even action in the US since KT trades ADRs on NYSE.

In February 2022, KT settled an SEC investigation by paying $6.3 million for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The SEC found that KT had, among other things, funneled money to lawmakers and maintained off-the-books funds to pay donations. KT neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing in the settlement, but it was a black mark that the U.S. regulator fined Korea’s largest telecom for corrupt practices. The company pledged to improve compliance.

However, fresh troubles arose in 2023. As the board was mulling Ku’s reappointment, Korean prosecutors launched a probe into allegations that KT executives gave preferential contracts to a certain vendor (KDFS) in exchange for kickbacks. In July 2023, prosecutors even raided the homes and offices of KT’s acting CEO (at the time) and two former CEOs, one being Ku Hyeon-mo and another Nam Joong-soo (who was KT’s CEO in the mid-2000s).

An audio recording apparently captured a contractor mentioning Ku and Nam in a scheme to award lucrative deals in return for benefits. Arrest warrants were issued for at least one KT-linked executive (a president of the contractor firm) on charges of breach of trust and embezzlement. This scandal is ongoing and has not been fully resolved in court, hence “unresolved scandal.” It basically casts a cloud over KT’s past leadership as Ku and Nam potentially face legal consequences for corruption. It’s striking (and disappointing) that KT’s two former CEOs have been implicated in alleged fraud.

These governance issues matter because they hint at a culture where either oversight was weak or management was too cozy with certain business partners and politicians. Even if the current CEO is clean, he has to clean up the mess and assure stakeholders that KT is turning a page. The new board chairman installed in 2023 was an independent director and former regulator (Yoon Jong-soo) to improve governance. They also added several new independent directors and reduced the number of internal directors.

There have also been labor and culture problems. In 2022, KT undertook a restructuring that moved many employees out of back-office roles into frontline sales positions after downsizing. This was extremely controversial internally and tragically was followed by a string of employee suicides. KT’s unions have been vocal against management decisions they view as harmful to workers. A new, labor-friendly government could scrutinize KT for such issues. It’s an extra facet of risk: discontent workforce and potential legal liabilities (if any cases find workplace negligence).

Despite past issues, the current management’s decisions on investments, balance sheet, and shareholder returns are reasonable. KT has kept its debt manageable (net debt-to-EBITDA 1.4x) and returns a chunk of earnings via dividends. The dividend policy has actually become more shareholder-friendly. The share buyback in 2025 is a shareholder value move that previous managements didn’t often do.

These are hopeful signs that the new leadership is mindful of investors.

Still, the overhang of governance failures means I apply some discount for corporate governance risk. It’s one reason KT’s stock is perpetually cheap relative to global peers; many investors just don’t trust the management to consistently act in shareholders’ best interest (especially when the government can intervene).

Valuation: DCF & Sum-of-the-Parts

To evaluate KT’s intrinsic value, I used two approaches: a DCF analysis and a Sum-of-the-Parts (SOTP) valuation. The DCF captures KT’s whole business cash generation, while the SOTP lets us value each division (telecom, finance, etc.) separately to see if the parts are worth more than the whole.

DCF Valuation

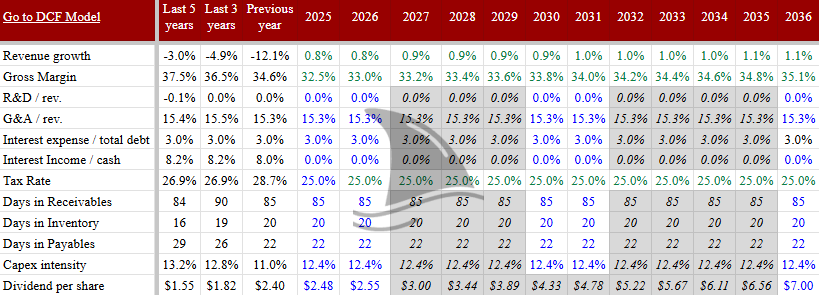

For the DCF, I utilized the assumptions below:

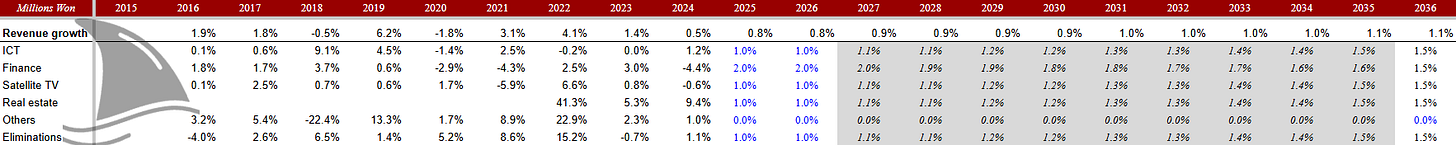

Revenue Growth

I assumed minimal growth in the core telecom revenues.

This is in line with Korea’s low industry growth (mobile service revenue is growing low-single-digits at best, and broadband/TV in the low single digits). I expect KT can eke out slight growth by upselling 5G upgrades and more expensive data plans, plus expanding its B2B cloud/AI services.

However, I also factor in declines in legacy areas (traditional phone lines keep shrinking, and satellite TV is declining).

This might even be a tad optimistic if competition intensifies or the economy slows. I’m not banking on any big top-line bump.

Profit Margins

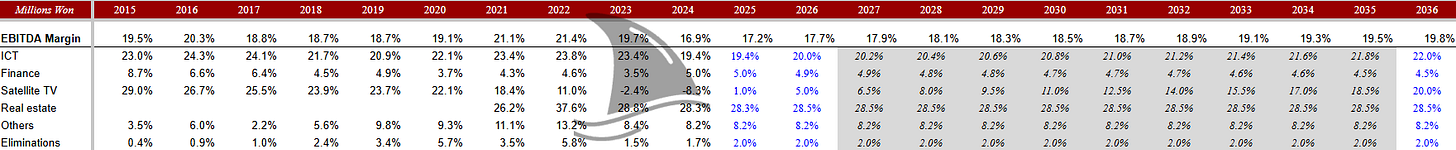

I anchor margins off segment EBITDA. Group EBITDA margin stepped down in 2024 to 16.9% (retirements and the Skylife drag), then recovers to 17.2% in 2025 and 17.7% in 2026. I fade in steady mix and cost wins to 18.5% by 2030 and 19.8% by 2036. That path lines up with how each business behaves.

ICT: 19.4% (2024) → 20.0% (2026) → 22.0% (2036). Assumes tighter subsidy discipline, a bigger B2B/IDC and cloud slice, and ongoing opex efficiency (automation in ops, lighter field costs). No heroics on pricing; most of the lift is mix and logistics.

Finance (BC Card): 5.0% in 2025 easing to 4.5% long-run. Interchange caps and competition keep a lid on it. Solid cash generator, not a margin engine.

Satellite TV (Skylife): from losses in 2023–24 to 1% (2025), 5% (2026), and a slow grind to 20% by 2036. The recovery assumes content cost normalization (I think this is unlikely), tighter packaging, and churn control via bundles; no big growth assumptions.

Real estate: 28.3–28.5% through the forecast. I treat large asset gains as non-recurring; the model carries ordinary leasing/development economics, not one-off flips.

Others: held at 8.2%. Conservative for a mixed bag of early-stage and services.

Eliminations: 2% drag to reflect intercompany.

This keeps the story simple: ICT does the heavy lifting, Skylife stops leaking and then contributes, card stays steady, real estate stays rich but non-core, and we don’t capitalize one-offs. If you later want a stricter case, cap Skylife at mid-teens EBITDA and ICT at 21%: the group ends 150–350 bps lower, which you can carry straight into valuation.

Capital Expenditures

Telcos are capex-intensive. KT has to invest in network maintenance, 5G expansion, future 6G, fiber upgrades, etc. I project capex will consume 12.4% of revenues annually which is in line with historical levels (a bit on the optimistic side).

KT’s cumulative capex was KRW 1.36T in first half 2025, which annualized is KRW 2.7T, about 9–10% of revenue. However, that figure excludes 5G spectrum costs and some investments in affiliates. If KT indeed pours 68% of its market cap into AI by 2027 as management proclaimed, that suggests a huge investment wave (though that figure likely includes operating expenses and investments, not just capex).

Working Capital

Telecoms usually don’t have big working capital swings. I keep working capital changes minimal in the model (some years slight use, some slight release).

Plugging these assumptions in, the DCF model yields a fair value of roughly $19.30 per ADR (1 ADR = 0.5 common shares). This $19.3 aligns very closely with the recent trading price (~$18.8), suggesting the stock is more or less fairly valued by the market.

For context, this equates to about 5.5x forward earnings and 0.7x book value, which is where KT has been trading. It also implies an EV/EBITDA in the 4x range, which is low, but ICT peers globally often trade 4–7x EV/EBITDA in markets with better growth or stability.

Even SKM sits around 4x EV/EBITDA lately and the “Korea discount” doesn’t spare the market leader. Historically SKM traded at a premium to domestic peers, but after the 2021 spin-off that moved stakes like SK hynix into SK Square, the story became a purer telco and, by 2023, the market priced it closer to KT. The overhang from subsidy-collusion investigations that began in 2023 (later ending in sector fines) also compressed multiples.

My fair value being so close to market price means there’s little margin of safety if my assumptions are off. And given all the uncertainties (regulation, competition, execution of AI projects), I’d want a significant discount to intrinsic value to invest, ideally +50% upside potential. I didn’t see that in DCF.

Even if I flex some inputs such as a slightly lower WACC, the DCF value tops out around maybe $23. On the downside, using more conservative assumptions (no margin improvement, or a higher equity risk premium) can justify a $11-$13 per ADR. This risk/reward around the current price didn’t excite me enough.

Sum-of-the-Parts Valuation

Sometimes a conglomerate like KT is worth more broken into pieces than as one entity. To double-check KT’s value, I did a sum-of-the-parts analysis, valuing each major segment separately and adding them up, then subtracting debt. Here’s what we found for each component (figures in USD):

Core Telecom/ICT Segment

I valued this segment at roughly $12.8–15.3 billion enterprise value. I arrived at that by applying a 5x to 6x EV/EBITDA multiple on the core telecom EBITDA of $2.6 billion. A 5–6x multiple is in line with global telecom peers for a business with low growth but stable cash flow.

I will be using $14B, that is a multiple of 5.5x.

Finance (BC Card and K-Bank)

I valued the Finance segment at roughly $550–830 million. The low end ($550M) assumes BC Card is worth about 5x its annual net income. BC Card is not publicly traded, but we know its revenues (~$3.5B annually) and that payment processing is low-margin.

Its net profit might be on the order of $100M or so. A 5x–8x P/E for a slow-growing financial service yields that $0.5–0.8B range. I lean toward the low end given competitive pressures in payments and the fact that BC Card has been partially subsidizing K-Bank (the internet bank hasn’t IPO’d and needed capital infusions).

If K-Bank becomes profitable or lists publicly, that could lift the Finance segment’s value toward the higher end. But conservative is best here, because fintech in Korea is crowded (KakaoBank, Kakaopay, Naver, traditional banks all in the fray).

I will be using a value of $740M for this segment.

Satellite TV (KT Skylife)

I assign no value to this segment. As mentioned, Skylife’s market cap is around $165M. The net value to KT’s shareholders is tiny relative to the whole. But I don’t even think it is worth the $165M, the business is not growing and faces structural decline.

Real Estate

As discussed, KT claims up to KRW 15T ($11B) potential value if they sold all properties. I don’t take that at face value for my base case. Instead, I assume a very modest $350–600 million value for real estate. My base case uses $475M.

This essentially capitalizes some steady real estate income. Why such a discount to KT’s own estimate? Because monetizing real estate takes time and can incur taxes and political pushback (selling off assets might draw public criticism if it involves layoffs or price hikes).

Also, KT might need some buildings for operations; they can’t all be sold. That said, I acknowledge real estate could be a swing factor. If KT got serious about unlocking value, it might spin off or REIT-ize these assets, potentially surprising the market. In Q2 2025, KT booked KRW 400B from a single project. So my $0.5B is likely very conservative. But again, I prefer to not over-count chickens before they hatch.

Other Ventures

This includes content (Studio Genie, etc.), cloud/datacenter business, IoT, and various minority stakes in tech companies. I assigned about $2.3 billion to this bucket.

How did we get that? Primarily from KT Cloud. KT spun off its cloud/data center unit and sought external investment. In 2023, a private equity fund (IMM) invested KRW 600B for a stake in KT Cloud, reportedly valuing it around KRW 4 trillion ($3B). There were also reports KT Cloud aimed for a KRW 4T valuation by raising more capital.

For the SOTP, I took roughly $2B to represent KT Cloud’s value (slightly discounting the high-end valuations), and added a few hundred million for the content and other smaller businesses. For example, KT’s Millie’s Library e-book unit is listed on the Kosdaq market, but it’s small. KT’s stake in the AI chip startup Rebellions was part of a $124M funding at $650M valuation.

Interesting, but immaterial to KT’s $9B size. So, $2.3B for “Others” is largely the cloud/datacenter operation’s value plus odds and ends.

Joint Ventures & Investments

I set $1 billion for KT’s miscellaneous JVs and stakes. The biggest item here is K-Bank. K-Bank has grown since launching in 2017, and in 2021 it raised capital at around a 1.7 trillion KRW valuation ($1.4B) when things were bullish (KakaoBank’s IPO gave a halo).

BC Card now owns about 34% of K-Bank. If K-Bank is worth say $1.5B, KT’s share is ~$500M. KT has JV investments in music streaming, maybe tower infrastructure, etc., plus stakes in some funds. I don’t have precise values for each, so $1B is a catch-all that seems reasonable as it the book value in the financials. It could be a bit higher if K-Bank’s value increases or if, say, KT’s stake in Hyundai Robotics (they had a venture with Hyundai) is counted.

Now, summing up the pieces:

ICT core $14B

Finance $0.74B

Satellite $0B

Real Estate $0.475B

Others (Cloud/Content) $2.3B

JVs/Investments $1B

That totals $18.5 billion enterprise value. From this, we must subtract net debt and minority interests to get equity value.

KT has a significant debt load but also cash. As of mid-2025, KT’s net debt was around $5.3. There are also minority interests. KT doesn’t own 100% of BC Card (a Korean bank owns a minority), nor 100% of Skylife (public minority), etc. Minority interest is $1.2B if we combine them.

Subtracting net debt and minority yields $12 billion in equity value. Divided by the number of shares comes out to $24 per ADR, 26% upside from current prices.

In a way, KT’s undervaluation is “deserved” given the governance issues and uncertain ROI on new ventures. The sum-of-parts shows there is break-up or restructuring value if an activist investor took control of KT and sold off BC Card, spun off KT Cloud, liquidated some real estate, etc., they might realize that full $24 per share value (or even more). But such a scenario is unlikely in Korea’s context, especially with government influence; KT is not going to be broken into pieces easily.

Therefore, while our SOTP indicates some upside, it’s not a high-conviction gap. The stock’s upside in the best realistic case ($24) isn’t huge enough to warrant the risks, and the timeline to unlock that value could be years. This aligns with our DCF result that KT is roughly fairly valued to modestly undervalued.

Risks

Investing in KT Corporation comes with several downside risks.

Regulatory & Political Risk: The Korean government exerts strong influence on the telecom sector, from price-mandates to CEO interference, which can upend strategy or earnings.

Demographics & Saturation: With mobile penetration already above 140% and a rapidly aging population, KT faces a flat or shrinking addressable market unless it invents new growth engines.

Technology & Capital Burn: KT’s ambitious push into AI/data-centres is broadly known, but it remains an execution risk—throwing billions into new ventures where telcos have no guarantee of winning.

Capital Misallocation & Governance: Beyond the above, the residual concern is that KT’s board or management may still invest in non-core businesses, fall prey to political deals, or fail to unlock hidden asset value in a timely fashion.

Verdict: Why I Passed on KT

After this deep-dive analysis, KT Corporation did not make the cut for the portfolio. Despite its superficially attractive features, KT fails to offer the margin of safety and competitive edge we look for in a top investment idea.

In the end, KT strikes me as a value trap: a company that looks cheap but is cheap for valid reasons. The lack of a moat, the history of returns below the cost of capital, and the overhang of governance issues all temper the enthusiasm that its 5x P/E and oligopoly position might otherwise evoke. One lesson I’ve learned is that sector structure alone doesn’t guarantee a good investment; it comes down to execution and shareholder alignment. In KT’s case, neither is clearly in the bag.

Could KT’s stock do okay? Sure. It pays a solid dividend and the business isn’t in danger of falling apart. We might see the share price grind up slowly if the company continues share buybacks or if the market re-rates telecom stocks generally. My analysis even shows a plausible upside to $24 per share if things go right. But “okay” isn’t enough for inclusion in our Beating the Tide best stock picks. I seek opportunities where we have high conviction of outsized returns.