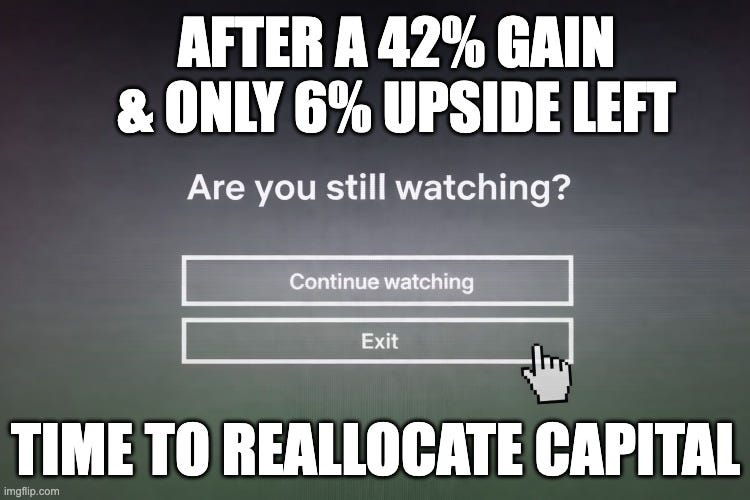

Why I’m Closing My Position in NatWest Group (NWG) After a 42% Run

NatWest’s valuation has caught up to its fundamentals. Solid bank, but better opportunities lie ahead.

I know this might sound surprising. Not long ago, I wrote about wanting more exposure to European banks as part of my diversification away from the US market.

Yet here I am, explaining why I’m closing one of those very positions.

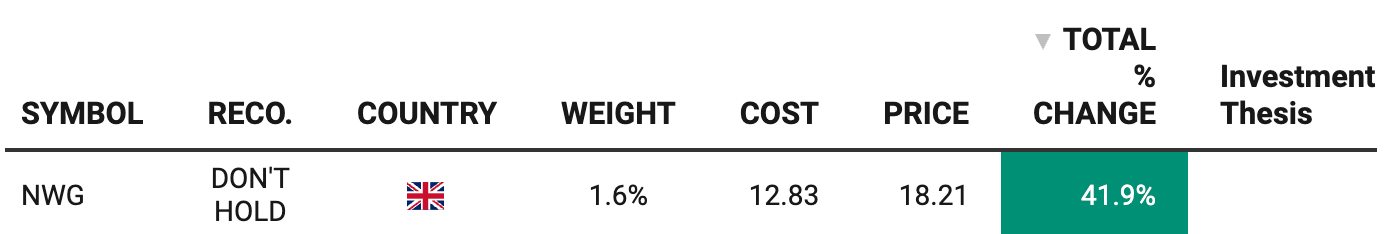

So what gives? It’s important to stay flexible. NatWest [NWG 0.00%↑] has performed well for me, and I’m closing the position after a 41.9% gain.

Back to the thesis…

In fact, it’s a strong bank with solid financials and a storied history. However, I have to constantly judge where each dollar will get the best return. And with NatWest’s stock now near my own estimate of fair value, I see limited upside left relative to other opportunities.

Think of it this way: NWG’s fundamentals have improved, but so has its stock price to the point that it’s not a screaming bargain anymore. Sure, it may still go up further, but my edge is smaller now. I’d rather reallocate those funds into something with more headroom.

TLDR

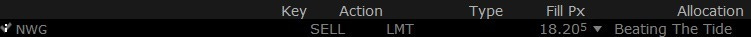

I’m closing my NWG position at around $18.21 per share. I estimate fair value at roughly $19.25, so the remaining upside (5.7%) is limited compared to other, better risk-adjusted opportunities. NatWest is a good business with a remarkable turnaround story, but at this point, I believe the position has run its course, and my capital can earn more elsewhere.

Trade alert

Close NWG

Table of Contents

Company History & Evolution

NWG’s story is one of rise, fall, and rebirth. The group’s roots trace back to the 18th century with the founding of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) in 1727, and later, the National Westminster Bank (NatWest) was formed in 1968 via a big merger.

RBS grew aggressively in the 2000s. Most notably with the ill-fated ABN Amro acquisition in 2007, a huge £49 billion deal that briefly made RBS the world’s largest bank. Unfortunately, this expansion came at exactly the wrong time. The global financial crisis hit in 2008, and RBS, laden with risky assets and overextended, collapsed into trouble.

It took a massive £45 billion UK government bailout in October 2008 to save RBS from insolvency. Taxpayers ended up owning 84% of the bank after that rescue, marking one of the largest bank bailouts ever.

Thus began a long decade of restructuring. Under government ownership, RBS was forced to shrink drastically. The bank cancelled dividends and bonuses, slashed tens of thousands of jobs, sold off non-core businesses, and significantly reduced its presence outside the UK to refocus as a UK-centric lender. Businesses like its U.S. retail bank (Citizens) were divested. The flashy empire built by former CEO Fred “the Shred” Goodwin was dismantled piece by piece, and RBS returned to its knitting: basic retail and commercial banking in the UK. It wasn’t easy, and RBS didn’t even return to annual profitability until 2017, nearly a decade after the crisis.

By 2020, with the turnaround in motion, management made a symbolic change: rebranding. The holding company RBS plc changed its name to NatWest Group plc, adopting the more consumer-friendly NatWest brand and shedding the tarnished RBS moniker. This name change acknowledged that most of its customer business was under the NatWest name (especially in England and Wales), and it aimed to turn the page on the crisis era.

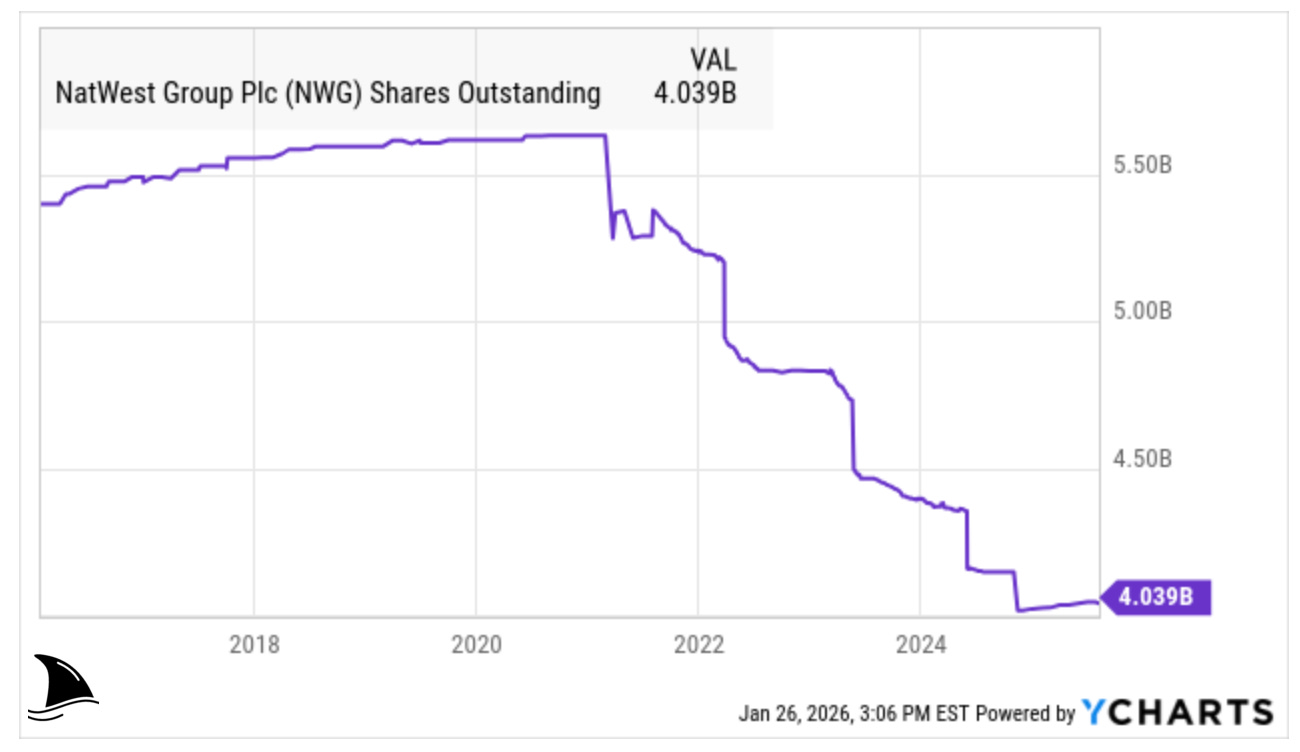

Meanwhile, the UK government slowly unwound its stake. Over the years, the Treasury sold down shares in chunks and through drip-feeding into the market. NWG itself helped accelerate this by buying back billions of pounds of its own shares from the government.

Fast forward to 2023–2025: the government stake fell to a minority and then to nearly zero. In fact, in May 2025, the UK fully exited its position and returning NatWest to full private ownership. This marked a major milestone, closing out a 17-year chapter of state ownership that began with the 2008 bailout.

Today’s NWG is essentially a leaner, domestically focused bank that emerged from that crucible. It has shed its global ambitions and now derives 90% of its income from the UK market. It operates a portfolio of well-known UK banking brands: NatWest (England/Wales retail and commercial), Royal Bank of Scotland (retail in Scotland), Ulster Bank (Northern Ireland), Coutts (private banking), and a slimmed-down investment banking arm (NatWest Markets).

This focus and simplification were deliberate. Management narrowed the bank’s scope to concentrate on serving UK retail and commercial customers while maintaining a conservative risk profile.

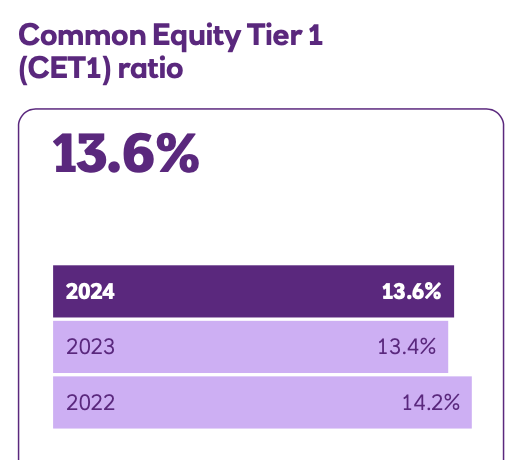

In 2022–2023, the bank was profitable and over-capitalized enough to start returning loads of cash to shareholders. By 2023, NatWest was posting strong earnings, and capital levels were well above regulatory minimums.

The combination of improved profits and excess capital allowed it to initiate hearty share buybacks.

In sum, NWG’s evolution took it from global giant to crisis victim to a reborn UK-focused bank. The company today is stable and profitable, but also a bit “mature” and staid. That lengthy turnaround unlocked a lot of value, much of which has already been reflected in the stock’s recovery.

I rode part of that journey. Now the question is: with the transformation complete and the government finally out, where does NWG go from here, and how much more upside is there?

How NatWest Makes Money

NWG’s business model is the epitome of a traditional bank; it makes money primarily by taking deposits and lending them out, earning a spread (interest margin), and charging fees for services.

Net Interest Income (NII)

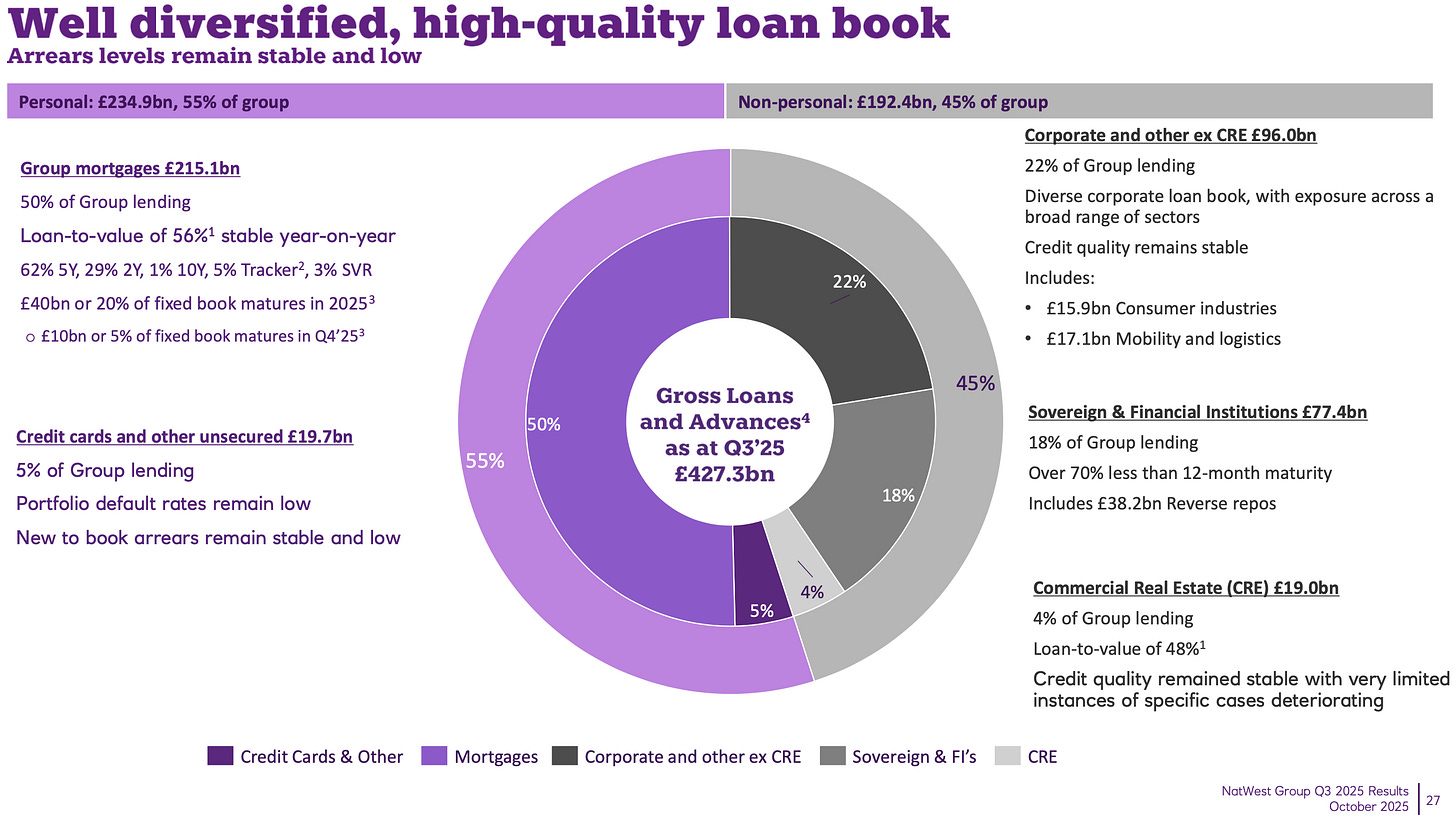

This is the biggest piece by far. NII is the difference between the interest the bank earns on loans (and investments) versus the interest it pays on deposits and funding. NWG has a loan book of around +£427 billion (mostly mortgages, corporate loans, and liquidity assets)…

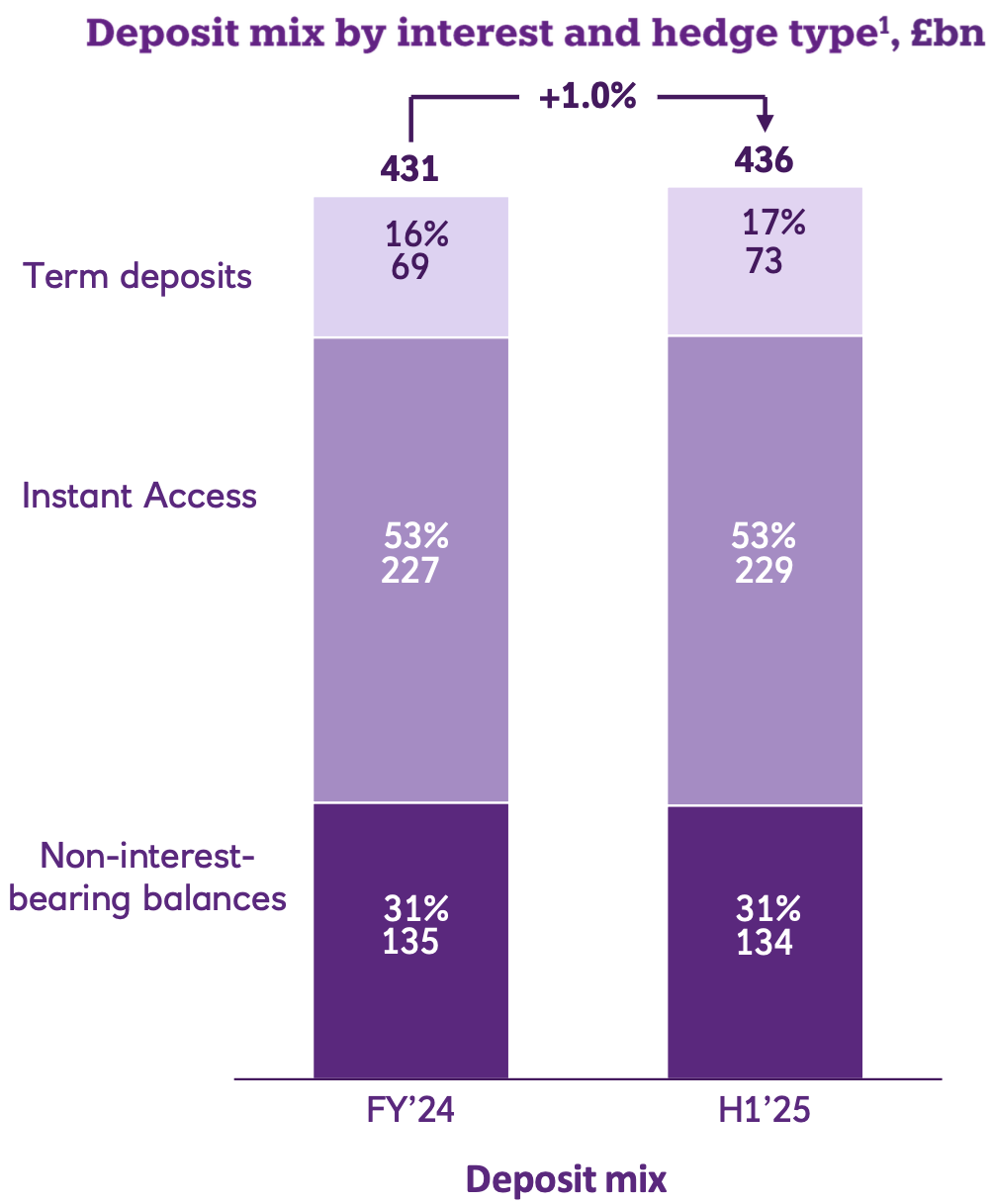

…funded by a slightly larger deposit base.

Because NWG’s deposits include a large portion of low or zero-interest accounts (like checking accounts), its cost of funding is very low. It can lend that money out at higher rates.

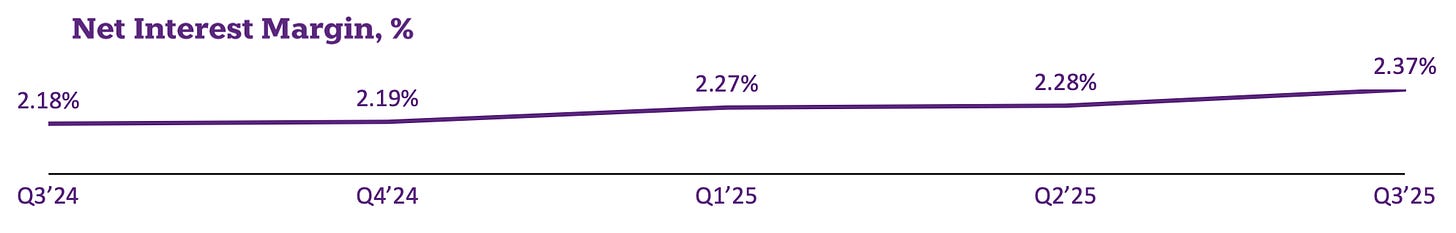

In recent years, as interest rates climbed, this spread widened, boosting NII. Its net interest margin (NIM), essentially the average yield on interest-earning assets minus cost of funds, has improved to about 2.37%.

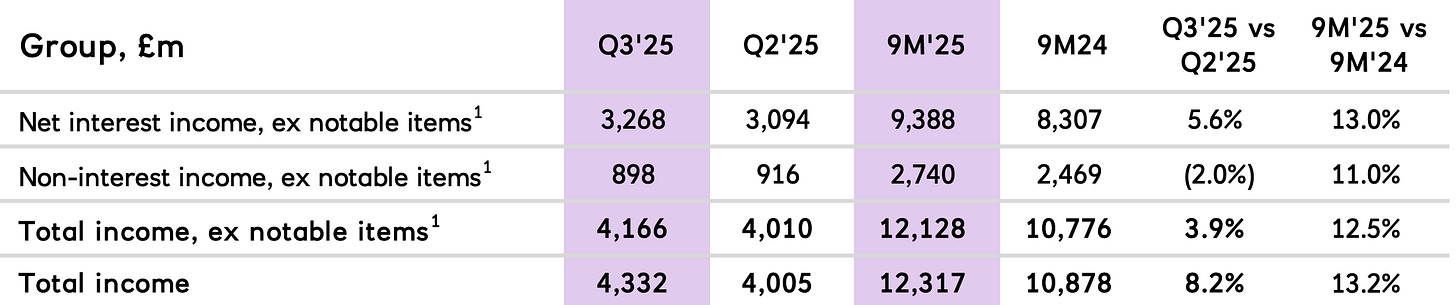

For the first nine months of 2025, NatWest’s total income was £12.1 billion (excluding one-off items), up a strong +12.5% y/y. This jump was driven largely by higher net interest income, thanks to rising rates and the bank’s ability to reprice loans faster than deposits.

Non-Interest Income

This includes fees, commissions, and other income. NWG earns fees from services like payment processing, credit cards, asset management (it has a sizeable wealth arm, including Coutts), insurance and investment product distribution, etc.

While important, these are a much smaller share of revenue than interest income. For perspective, NII made up 77.5% of NWG’s total income in 9M 2025, with fees and other income representing 22.5%. Management has been trying to boost fee-based income to diversify revenue.

For example, focusing on wealth management and insurance sales, and pushing more transactional fees. But growth there is modest. The UK banking market is competitive, and NWG’s non-interest income has been fairly flat. Still, it provides some buffer when interest margins are under pressure.

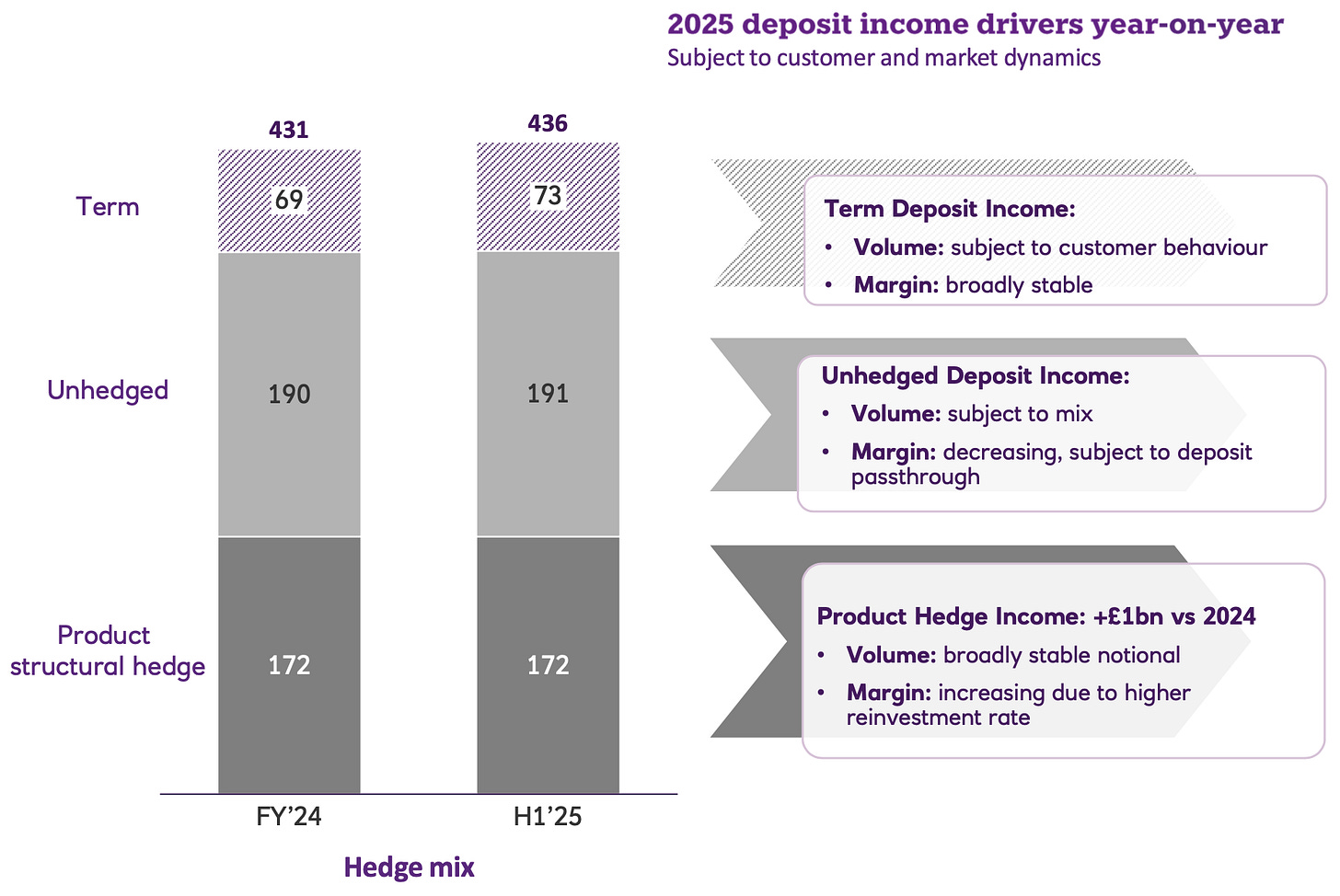

“Structural Hedge” Income

A technical but important part of NWG’s interest income is the structural hedge.

NWG sits on a large deposit base that behaves like long-dated funding, even though customers can withdraw whenever they want. The bank treats a portion of those deposits as “sticky” and hedges them using a rolling book of receive-fixed interest rate swaps and, in some cases, bonds. This turns part of the deposit base into a more predictable stream of income.

The key word is rolling. These hedges do not reset overnight. As older swaps mature, NWG replaces them at prevailing market rates. That creates a lag. The hedge can continue to support income for a period after base rates fall. It can also delay the full benefit when rates rise.

In Q3 2025, NWG said the structural hedge continued to support deposit margins and guided that this effect should remain in place into 2026–2027.

If you want a great, plain-English primer on how structural hedges actually work, Robin Down wrote one that is genuinely worth reading:

This helped offset pressure in areas like mortgages. It’s a temporary boost (hedges will roll off in a few years), but meaningful.

Cost Side

While not an income source, it’s worth mentioning NWG’s cost structure since profitability = revenue minus costs. The bank has worked to control expenses through efficiency programs and branch closures, although inflation put upward pressure on costs recently.

In Q3 2025, NWG’s 9M operating expenses were £5.9B (up +2.5% y/y, which is decent). The cost-to-income ratio stands around 46%, which is decent for a retail-oriented bank (not the absolute best, but reasonably efficient). NWG has invested in digitalization (its mobile banking app and AI chatbot (“Cora”)) to improve efficiency and customer service.

In recent years, the digital assistant Cora has handled 11 million customer conversations per year, with about half of those needing no human intervention. That reflects meaningful adoption of AI and digital service tools across the bank’s customer base, helping improve efficiency and support scalability.

The recent financial performance shows this model firing on all cylinders: through 9M 2025, NWG delivered an attributable profit of £4.1 billion and an impressive 19.5% return on tangible equity (RoTE). These are strong numbers for a bank, indicating healthy margins and prudent risk (we’ll talk risk soon). The bank’s capital ratio (CET1 14.2%) is also solid, meaning it’s well-capitalized.

However, banking is a cyclical business. The conditions that allowed NWG to earn almost 20% RoTE, mainly high interest rates and ultra-low loan losses, won’t last forever.

Industry Landscape, Growth Levers & Outlook

NWG operates in the UK retail and commercial banking industry, which is mature and highly competitive. The UK banking market is dominated by a few large players (NatWest, Lloyds, Barclays, HSBC, and to an extent Nationwide Building Society), making it an oligopoly of sorts. Yet competition, especially in key products like mortgages, is intense.

Overall growth in this industry is slow. Banks fight for market share in a pretty saturated market, and overall lending tends to grow only a few percent per year in line with the economy (low-single-digit loan growth is the norm, roughly 2% annual growth is my base case). So NWG’s strategy isn’t about explosive growth, but rather about maintaining its share, optimizing margins, and improving efficiency.

One advantage NWG has is a bit of an economic moat in its home market. It does enjoy a structural edge: mainly its low-cost funding and large scale in the UK. Thanks to its big deposit franchise, NWG can raise funding more cheaply than smaller rivals. A huge chunk of those deposits are current accounts paying near 0% interest.

This cost advantage is hard for new entrants to replicate, because barriers to entry in banking may be low, but barriers to scale are high. You can start a digital bank in your garage, but accumulating millions of retail customers and their deposits takes years (or massive marketing spend). NWG’s scale also helps spread its IT and compliance costs. All that said, it’s a narrow moat, not a wide one.

The growth outlook for UK banks like NWG is relatively subdued. There aren’t many untapped markets or unmet credit needs; everyone already has a bank account, a mortgage, etc. NWG’s own strategy is “prudent, low-risk growth.” They aim to defend their market share in core areas (particularly mortgages) and selectively expand in fee businesses.

For instance, NWG has a high market share in low loan-to-value mortgages (the safer end of the mortgage market) and intends to keep writing new mortgages at least at the pace of its old loans rolling off. It even did a bolt-on acquisition of a £2.5 billion chunk of prime mortgages from Metro Bank in 2024 to bolster its loan book. But even with that, net mortgage growth was tepid because many customers refinanced or paid down loans.

This underscores a reality: mortgage lending is cutthroat in the UK right now. There’s heavy competition on rates, especially as overall demand has cooled with higher interest rates. NWG acknowledges margins on new mortgages are under pressure. However, the bank still finds it worthwhile to write low-risk mortgages using its cheap funding (even if margins are thin) because it earns something and keeps customers in the franchise.

Another lever for growth is pushing into more non-interest income areas. NWG, like Lloyds, has been targeting the “mass affluent” segment to sell wealth management and investment products (for example, Lloyds partnered with Schroders and now is buying out that JV to grow its wealth business). These efforts could yield higher fee income over time, but it’s incremental, not a game-changer in the near term.

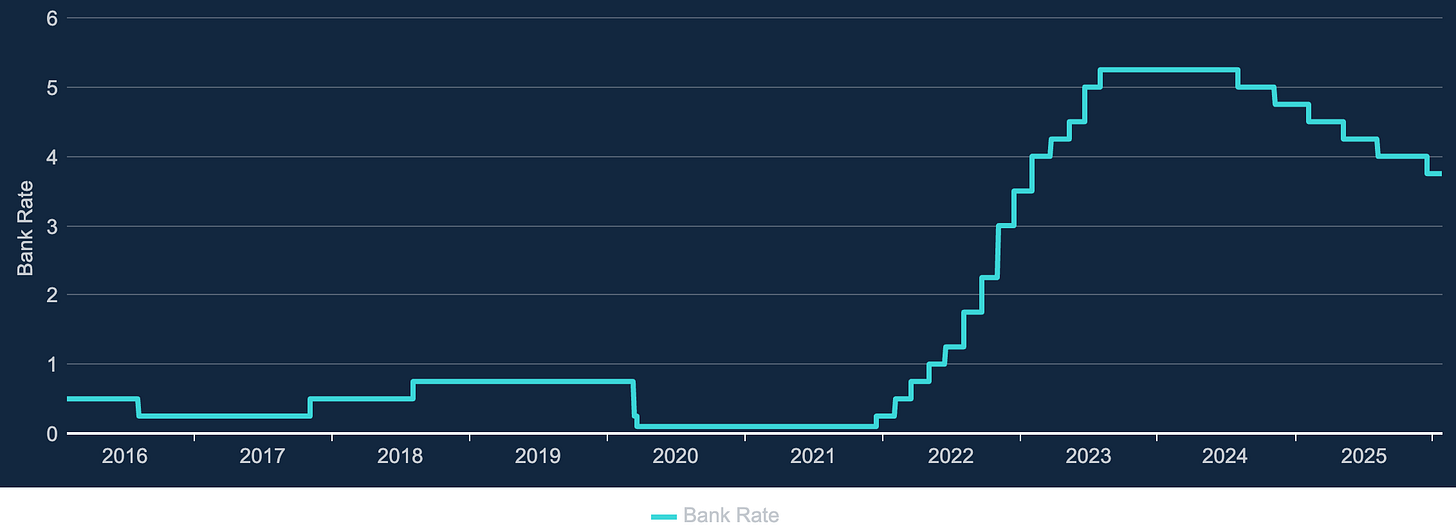

The macro environment is a big factor in the outlook. The past couple of years saw surging BoE base rates, which went from near 0% in 2021 to over 5% by mid-2023.

That was a boon for banks’ NII. Now, however, the tide is turning: the BoE actually started cutting rates in late 2024 as inflation came off a boil. It cut the official rate from 5.25% to 3.75% by late 2025.

Structural hedges are one reason bank margins often peak after base rates peak, because the hedge book reprices gradually rather than all at once. I expect net interest margins to crest around 2.4–2.6% by 2027, and then pull back slightly as older high-rate hedges roll off and competition forces higher deposit rates.

I think that bank NIMs will peak at roughly 260 basis points in 2027 before the tailwinds fade. The structural hedge is still pushing NIM upward for the next year or two, offsetting initial base rate cuts. But by the late 2020s, that support ebbs.

So, we have a slowing top-line outlook: loan growth ~2% annually, and NIM that is near peak. That implies revenue will plateau or grow modestly at best in the medium term (absent some big economic boom or M&A, which seems unlikely as NWG itself even said it doesn’t expect to be involved in major acquisitions, given the concentrated market).

One more aspect of the industry landscape: regulation and political environment. UK banks are tightly regulated, and there’s also public and political scrutiny. For example, when rates jumped, UK politicians pressured banks for not raising deposit savings rates fast enough so there’s always a risk that regulators force more “fair” pricing that could squeeze margins. Also, there’s a bank levy and occasional talk of windfall taxes on banks’ profits. So far nothing drastic has materialized on that front, but it’s a background risk (we’ll cover more in risks section).

The bank itself improved its guidance for 2025 earnings (now expecting >£16.3B income and >18% RoTE), showing confidence in the near-term. But beyond that, consensus is that things normalize to lower growth.

Competitors and NatWest’s Edge (and Limits)

Lloyds

Lloyds [LYG 0.00%↑] is the UK’s largest retail bank and arguably NWG’s closest comparable. Lloyds has an even bigger share of the UK mortgage market and a similarly giant deposit base. Both Lloyds and NatWest have low funding costs due to their scale and high proportion of non-interest-bearing deposits. These two really benefit the most from cheap funding in the UK.

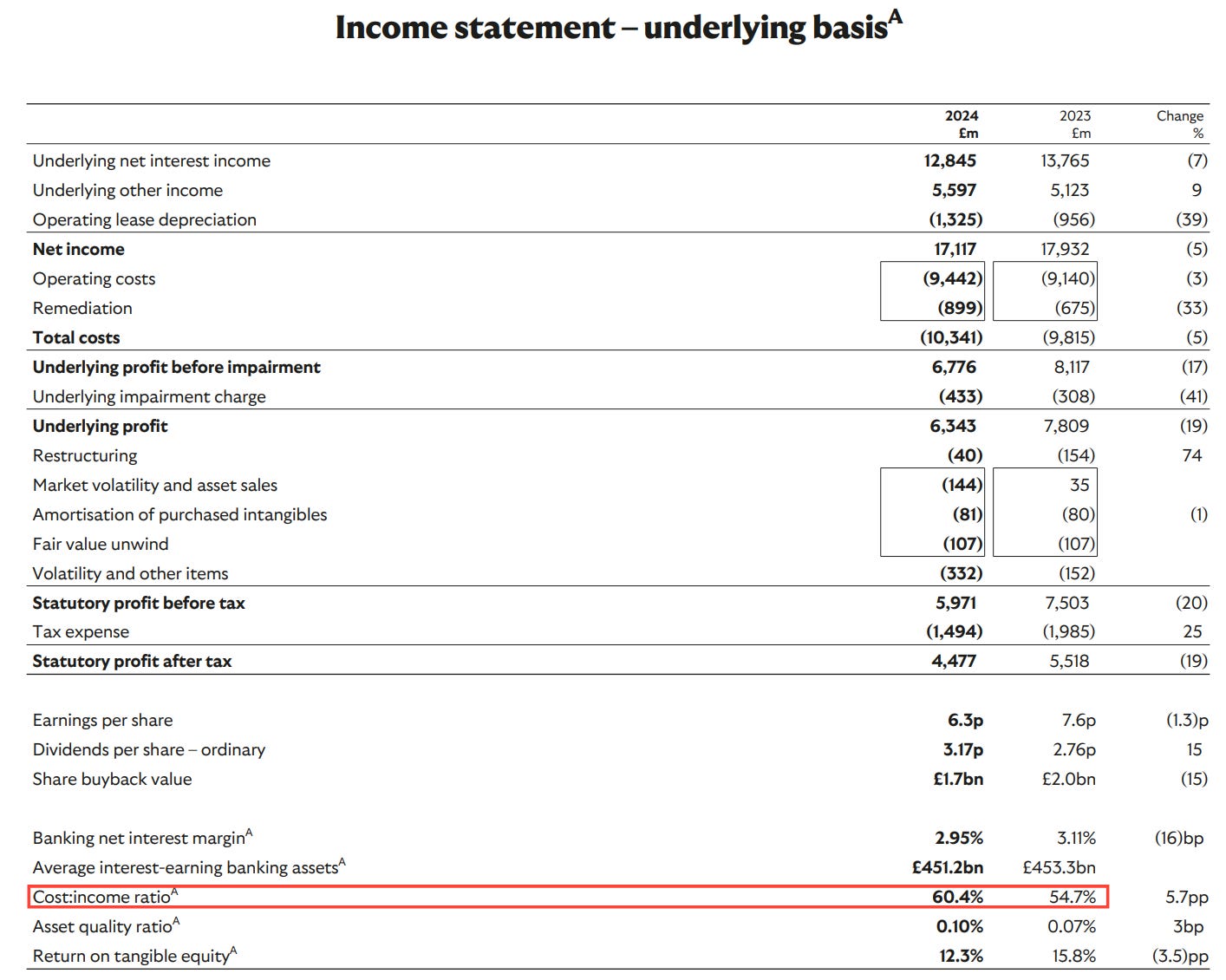

LYG has often been competitive on efficiency, with a 54.7% cost-to-income ratio in 2023, broadly similar to NWG’s low-50s profile, though LYG’ ratio rose in 2024 to 60.4%.

Right now, though, NWG outshines LYG on profitability: NatWest delivered 19.5% RoTE YTD through Q3 2025, while Lloyds guides to 12% RoTE for full-year 2025, or 14% excluding the motor finance charge.

The divergence is not accidental. NWG entered the rate cycle with a more favourable structural hedge profile, which allowed NII to keep rising even as deposit competition intensified. At the same time, LYG’ earnings took a hit from higher remediation costs and a more retail-heavy balance sheet, which is more sensitive to savings rate pressure. The result is that NWG’s returns continued to climb while Lloyds’ stalled, even before accounting for one-off charges.

Part of that gap is one-off. Lloyds took an £800m provision linked to the motor finance mis-selling issue. Excluding that, Lloyds’ RoTE was 14.6% YTD.

In essence, NWG has been executing better recently, aided by its hedge positioning and perhaps slightly different asset mix. Both banks, however, face the same headwinds: intense mortgage competition, pressure to raise savings rates, and limited loan growth.

Lloyds’ strategy has been to double down on cross-selling insurance and wealth products to its huge customer base (similar to NWG’s approach). Neither has a huge advantage over the other in core banking; they’re more like heavyweights trading punches in the same ring. NWG’s edge could be its more commercial client base (NWG has a significant commercial lending business as well, whereas Lloyds is very retail-heavy) and possibly a bit more agility after its restructuring. But Lloyds is very strong in UK banking too, so NWG can’t let up its game or Lloyds will poach customers.

Barclays (BCS)

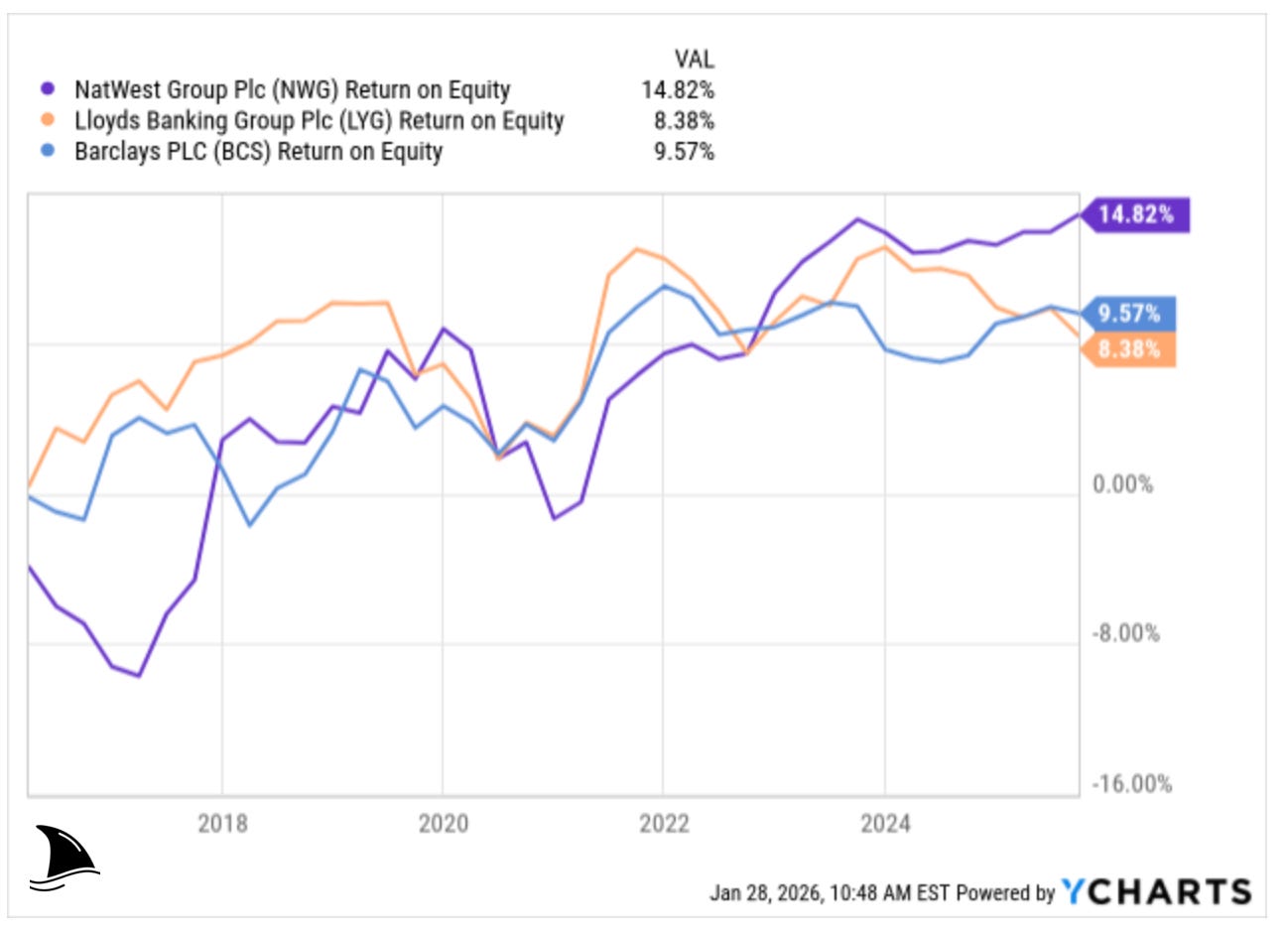

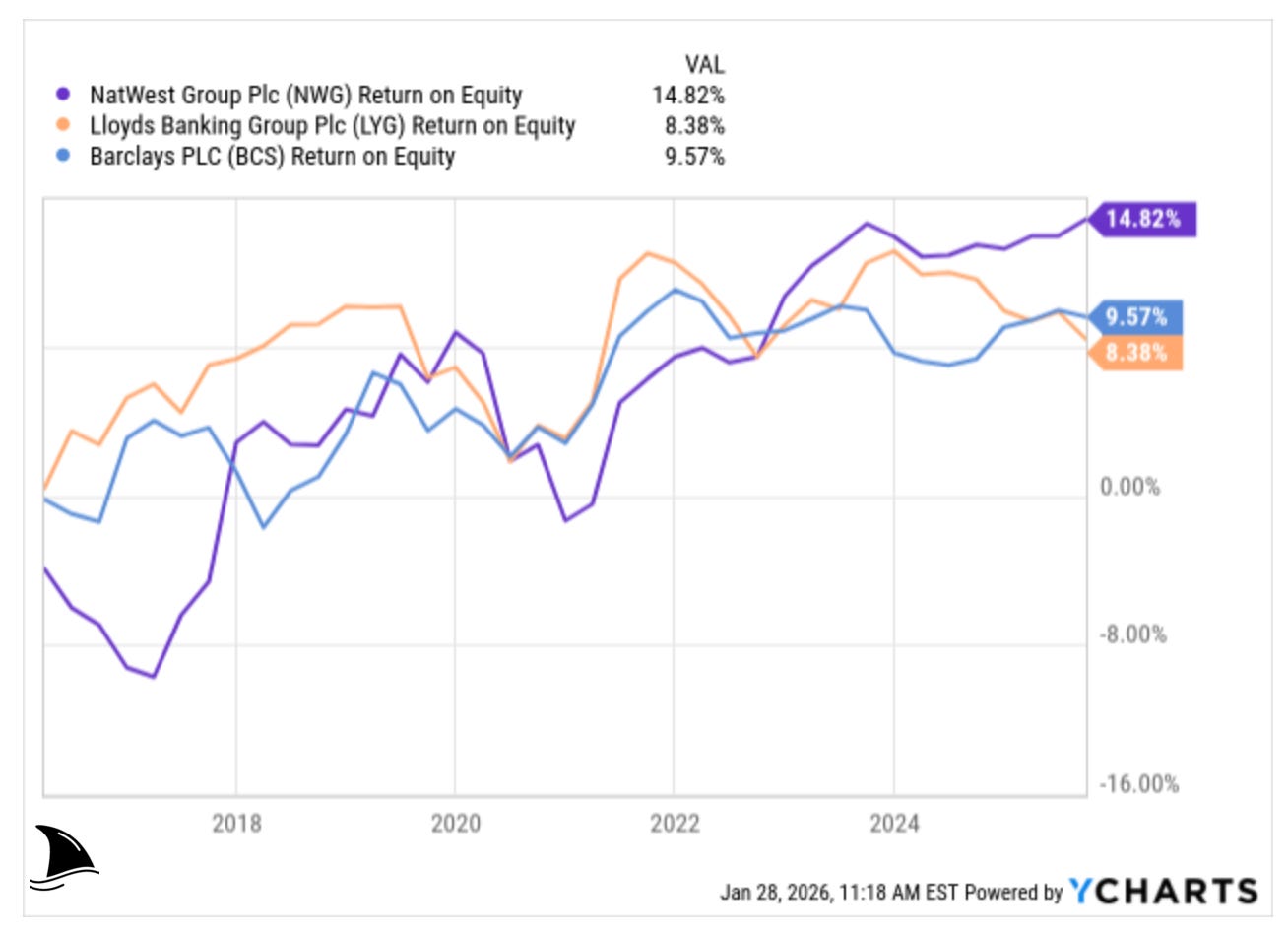

Barclays [BCS 0.00%↑] is a different beast because it has a large investment banking arm (Barclays Capital) alongside UK consumer banking. This makes Barclays’s performance more volatile, and historically, its returns have lagged purely domestic rivals.

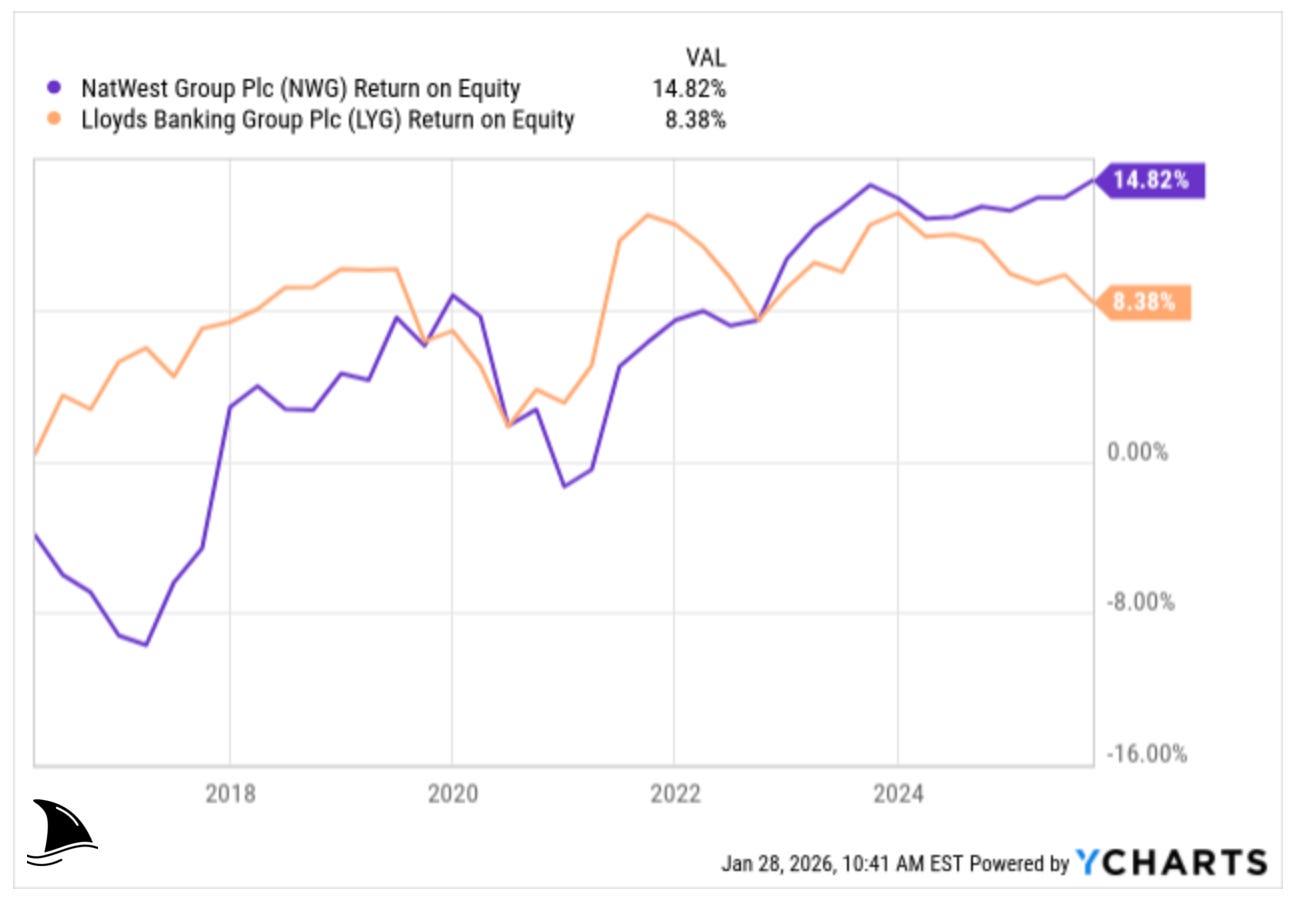

You can see this clearly in the ROE history. Barclays has periods where returns rebound sharply and even approach peers, but those gains tend to fade as market conditions turn. Over full cycles, that volatility has translated into lower and less predictable returns than the more domestically focused UK banks.

Barclays’ RoTE has generally hovered around the high-single to low-double digits in recent years, and the bank is targeting more than 12% by 2026. That remains below what NWG is delivering today. Why? The investment bank’s earnings are less consistent and require a lot of capital for relatively lower returns.

From a competition standpoint, Barclays in the UK retail market is a player (they have a big credit card business and a solid mortgage share), but they aren’t as dominant in the UK retail as Lloyds/NatWest. NWG’s advantage over Barclays is that it’s a pure play on UK retail/commercial banking, without the drag of a trading business.

In fact, NWG consciously shrank its capital markets division to a small supporting role. The flip side is that Barclays can potentially diversify revenue more if UK banking margins shrink, since it has global markets and credit card fees, etc. But generally, NWG and Lloyds have higher-quality, more stable earnings than Barclays due to their focus on traditional banking. Investors often give Barclays a lower valuation (relative to book value) because of this lower quality of earnings.

Challenger Banks & Others

Beyond the big legacy banks, the UK has a cohort of smaller challenger banks (like Monzo, Starling, Revolut on the fintech side, and some mid-tier banks like Santander UK, Virgin Money, Metro Bank, etc.).

Thus far, NWG and peers have held their own against these newcomers, but not without pressure. The challengers tend to cherry-pick certain products: e.g., digital upstarts offer slick mobile banking and often attractive rates on deposits or low-cost loans to attract customers. When interest rates were very low, some fintechs struggled to profit, but as rates decline again, competition from challenger banks could intensify. They might lure rate-sensitive savers by offering higher deposit yields than big banks, or target younger customers with app-based services.

NWG has responded by improving its digital offerings (as mentioned, millions use its app and AI chat). It even partnered with tech companies (for example, it is working with an AI platform on fraud detection and digital assistant features). Still, customer churn is a risk as UK customers can and do switch banks, especially for better rates or service. NWG experienced a bit of that: organically, it was losing mortgage market share until it bought that portfolio from Metro Bank to plug the gap. It shows that despite having advantages, it doesn’t have an impregnable moat, and competitors nibbled away at its share in some areas.

Management and Capital Allocation

I have to give credit to NWG’s management team for the bank’s renaissance over the past several years. They executed a massive restructuring and refocused the bank on its core strengths.

After the financial crisis, Stephen Hester took the helm of RBS/NatWest to guide the initial restructuring from 2008 to 2013, followed by Ross McEwan from 2013 to 2019 as the bank refocused on UK retail. In November 2019, Dame Alison Rose became CEO and she remained in the role until her July 2023 resignation. Paul Thwaite was appointed interim CEO in July 2023 and was confirmed as CEO in February 2024. Despite some leadership changes, the strategic direction remained consistent: de-risk, simplify, and then return capital.

In terms of quality of leadership, I’d say management is competent and conservative. They navigated the pandemic and post-pandemic inflation environment pretty well. For example, they set cautious loan loss assumptions (which proved more than enough as credit losses stayed low) and they avoided the temptation to chase risky lending for growth.

The fact that its RoTE jumped to 19–20% in 2023–2025, exceeding even their own targets, shows they managed the interest rate cycle superbly. In 2024, it earned £4.5B net income with a RoTE of 17.5%, and by 9M 2025, RoTE was 19.5% vs 17.0% a year prior. Management even felt confident enough to raise guidance multiple times (e.g. bumping 2025 expected RoTE from 16.5% to above 18% during 2025).

Where management really shines is capital allocation, specifically, returning excess capital to shareholders. The bank has more capital than it needs, and rather than hoard it, they’ve been giving it back through dividends and buybacks. In 2023, it returned £3.6 billion to shareholders in total. This included ordinary dividends and substantial share buybacks. Notably, they executed a £1.3B directed buyback (purchasing shares directly from the UK government as part of the privatization) and additional on-market buybacks. This capital return was on top of maintaining a very strong capital buffer (CET1 >14%).

Management has a clear capital return policy: pay out around 50% of earnings as a dividend, and use surplus capital for share buybacks (subject to maintaining a comfortable buffer above regulatory capital requirements). Essentially, once NWG has enough capital to support growth and meet regulations, they’re not looking to do empire-building acquisitions; they’ll give the money back to investors. I like this discipline. It prevents value-destructive adventures and rewards shareholders in real time.

Another positive on capital allocation: NWG has been selective with any inorganic moves. For example, the small “bolt-on” acquisitions mentioned (like that Metro mortgage portfolio, and some fintech investments) have been modest in size and strategic in nature. Management isn’t overpaying for big mergers; they know organic growth and buybacks are likely more accretive.

It’s also worth noting that, having come out of government ownership, management is now free to focus purely on shareholder value. For years, there was an overhang that the government (as majority owner) might prioritize political objectives or constrain the bank’s payouts. Now that’s largely gone. That’s a subtle but important change, as it can fully be run for profit now, just like any private bank.

Valuation: Fair Value Around $19.25

At $18.21 per share, the stock isn’t exactly expensive on an absolute basis (banks rarely have high P/E multiples), but it’s also not the bargain it once was. I’m closing my position largely because I think the intrinsic value is around $19.25 per share, which means the upside from here is modest.

Earnings and Returns Outlook

I’m assuming NWG can sustain a mid-cycle RoTE of about 16% going forward, once things normalize. This is a bit lower than the nearly 19-20% it’s hitting in the current peak environment, but reflects a more “normal” scenario with slightly lower margins and higher credit costs.

Market pricing today

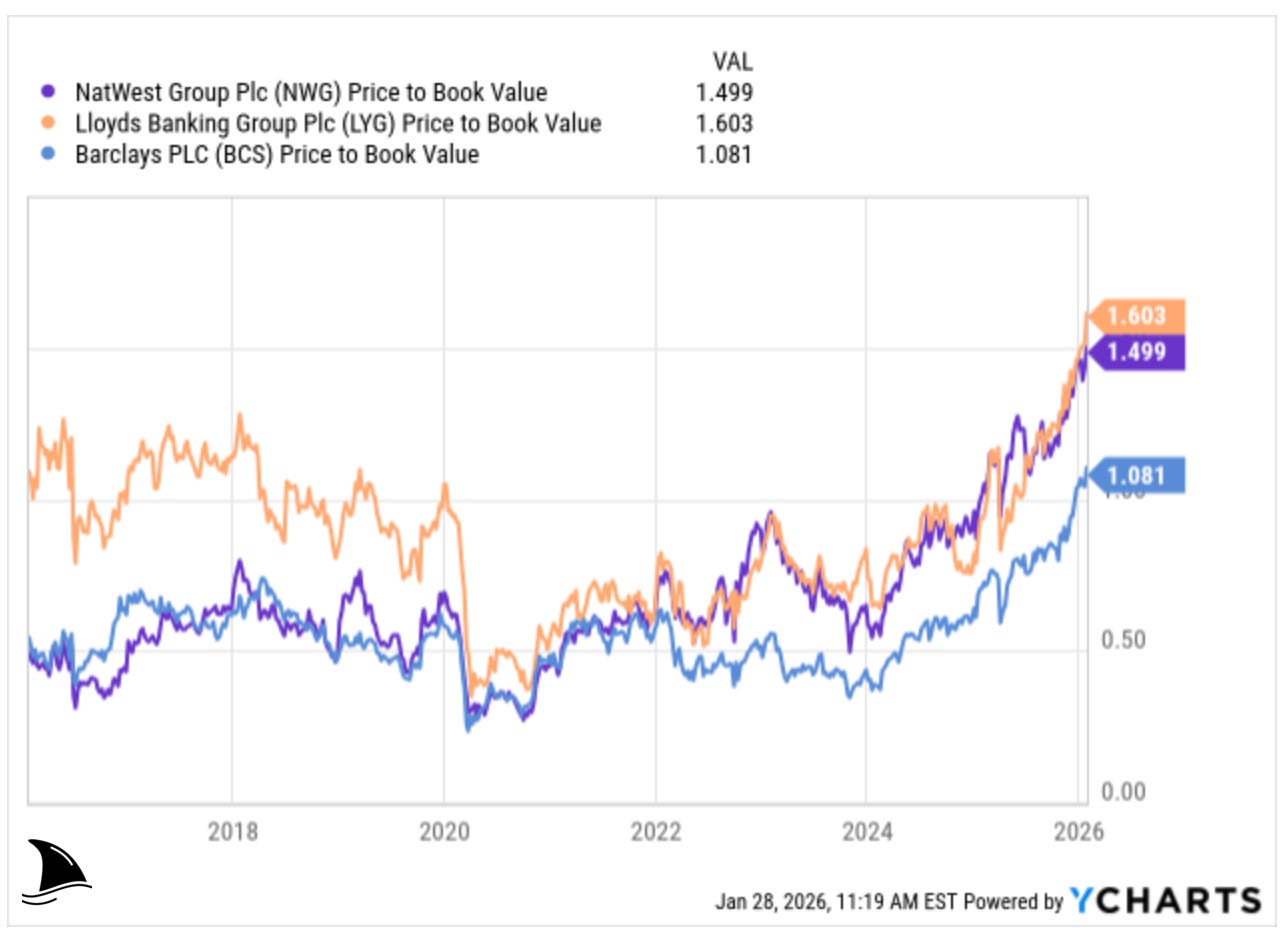

The market has not missed NWG’s improvement. As the chart below shows, NWG now generates materially higher ROE than both LYG and BCS. This gap opened during the rate cycle as NatWest benefited from stronger margin expansion and cleaner execution. That surge in ROE explains why the stock has re-rated over the past two years.

That improvement in returns has already translated into valuation. NWG now trades at 1.5x book value, broadly in line with Lloyds and well above Barclays. Historically, UK banks only sustain multiples above book when returns are comfortably in the mid-teens. With NWG already priced for that outcome, further multiple expansion requires returns to stay near peak levels for longer.

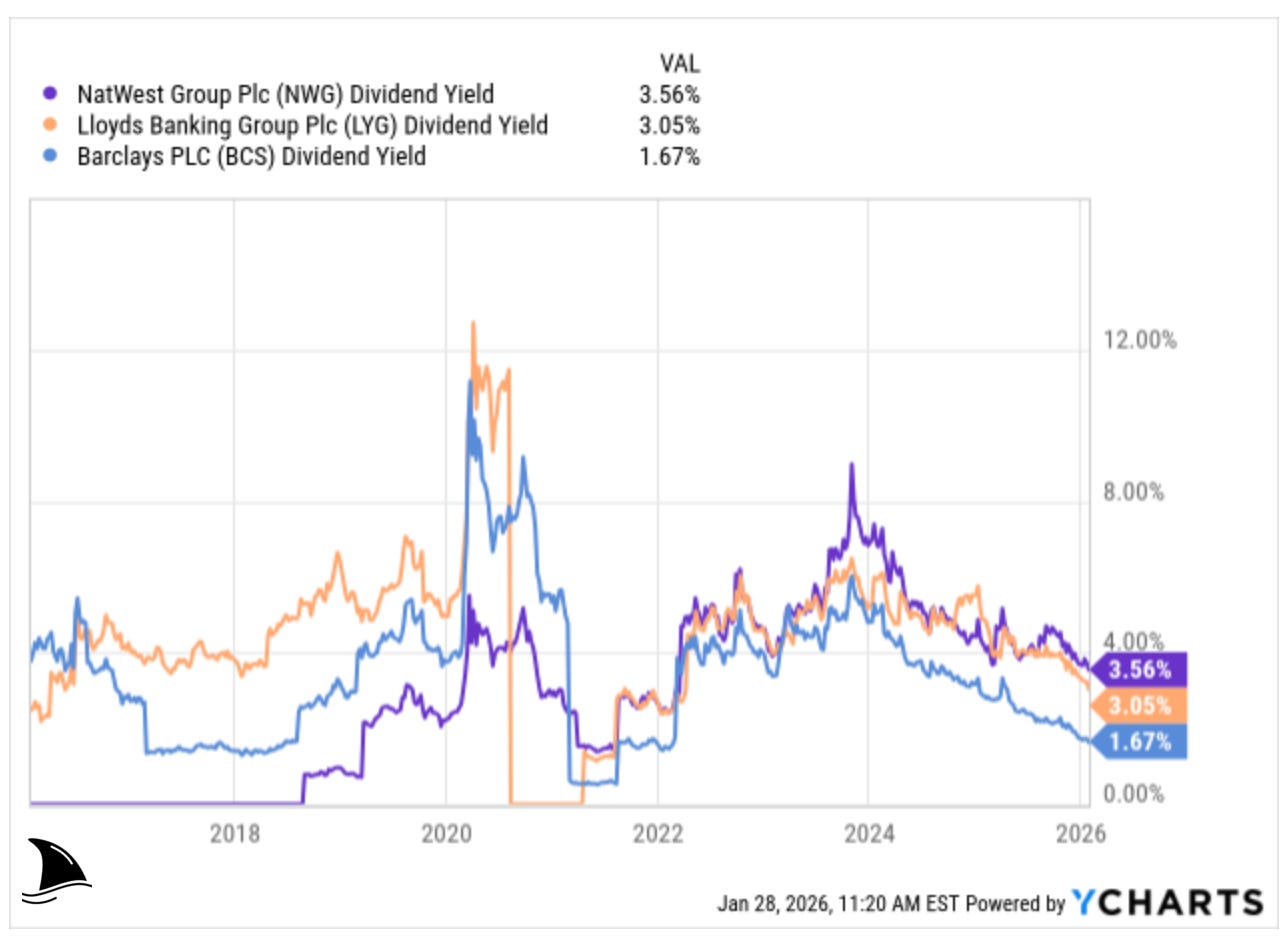

Income investors still get paid, but even here, the story has matured. NWG’s dividend yield sits in the mid-3% range, slightly ahead of Lloyds and well above Barclays, but no longer high enough to compensate for valuation risk if earnings normalize. At today’s price, most of the shareholder return will come from earnings delivery, not from re-rating.

Net Interest Margin

As discussed, I model NIM peaking around 2.6% by 2027, then flattening or slightly contracting thereafter. This assumes the rolling structural hedge keeps the average hedge yield elevated for a period even as base rates decline, because only a portion of the hedge book resets each year as swaps roll off.

At 2.6% NIM, NWG would be near the top of its historical range. Beyond 2027, as hedges roll off and competition potentially forces higher deposit rates, I’d expect NIM to drift back down towards 2.0% in the longer run. So, no further expansion beyond 2027 in my model.

Loan Growth

I assume a loan growth of 2% per year through the forecast period. This is consistent with UK economic growth and NWG maintaining its share. It might grow a tad faster in some segments (like credit cards or small business) and slower in others (like mortgages, if housing remains soft), but 2% blended feels conservative.

If the bank outperforms and grows loans faster without sacrificing margin, that would be upside to my valuation. But given the competitive landscape, I’m not counting on much more.

Credit Losses (Impairments)

This is a big one. The past few years have seen exceptionally low loan losses: NWG’s cost of risk was only 9 bps in 2024, and even with some normalization, it’s guided to under 20 bps near-term.

However, I expect credit costs to rise toward more normal levels over the cycle. My valuation models 20 bps of impairments in 2025 (what management guided, slightly below their 20 bps forecast) and then a rise to 40 bps at the mid-cycle. 30 bps (0.3% of loans) is still a fairly benign credit cost by historical standards, but it’s much higher than recent ultra-low levels.

Why increase?

Because as the economy goes through a typical cycle, some borrowers will default, especially those who were stretched by high interest rates and then face recession or unemployment. It’s prudent to assume the good times of near-zero defaults won’t last.

In absolute terms, 30 bps of losses on a £427B loan book is about £1.3B of impairments in a year, which is manageable given pre-provision profits, but it will dent the bottom line compared to today, where impairments are like £300–£500M. So this is a key normalization in my model that reduces mid-cycle ROE from the current lofty levels.

Cost of Equity

I use a 9% cost of equity. This reflects a low risk profile. With strong capital ratios and a domestically diversified loan book, I think 9% is a fair required return.

If anything, one could argue for slightly lower (8-8.5%) because of the stability, but I’ll stick to 9% to be on the safe side, given some remaining macro risks (UK economy isn’t risk-free).

Valuation Method

I primarily rely on a dividend discount / excess capital return model and cross-check with Price/Tangible Book multiples. Given NWG’s plan to pay out 60-70% of earnings (dividends + buybacks combined) over time, the DDM is appropriate.

Using the above assumptions, I project earnings over the next few years, apply the payout, etc. The result is that $19.25 per share is around the present fair value. In terms of multiples, that equates to 1.6x book.

Given $18.21 vs $19.25, the margin of safety is thin. It’s about 5.7% upside to fair value. The upside is not compelling, especially considering that bank earnings can be quite cyclical, and one macro hiccup (e.g. a recession) could cause the stock to drop much more than 5.7%.

In other words, at this price the risk/reward is no longer skewed massively in our favour. When I originally invested in NWG, it was at a much larger discount to book value and pessimism around UK banks was higher, so the upside was significant if things improved (which they did). Now optimism has returned, the bank is firing on all cylinders, and the valuation reflects a lot of that good news.

To put it simply: NWG is now fairly valued for a moderate-growth, mid-teen ROE bank. If you hold the stock from here, you’ll likely get the dividend (3% to 4%) and maybe a bit of capital appreciation in line with earnings growth, but you’re unlikely to get another big multiple expansion or windfall.

Could the stock overshoot my fair value? Sure, markets can get exuberant. Maybe some will pay 1.8x book if RoTE stay 18% for longer. That could push the ADR into the low $20s. But that would be stretching the valuation in my view, and leaves little room for error.

On the downside, if anything goes awry (say credit losses jump or margins compress faster), the stock could de-rate back to book value or below. That dual-sided scenario (small upside if all goes perfectly, bigger downside if things go wrong) is exactly when I prefer to exit a position.

Key Risks and Uncertainties

Risk #1. Credit Quality Deterioration

The benign credit conditions won’t last forever. Loan impairment charges are likely to normalize upwards from the current ultra-low levels. If the UK economy hits a rough patch (rising unemployment, falling house prices, etc.), NWG could see borrowers default at higher rates.

Sectors like unsecured consumer lending or commercial real estate are potential weak spots. A recession could push loan losses well above my 30 bps assumption, which would directly eat into earnings and capital. In severe scenarios, profits could plunge, and capital ratios could be tested. NWG’s fortunes are closely tied to the UK economy, so any macro downturn is a clear risk.

Risk #2. Net Interest Margin Pressure

We’ve enjoyed rising NIM, but going forward, margin pressure is a risk on multiple fronts. Firstly, as base rates fall, NWG will feel a squeeze as interest income will decline unless it can lower deposit costs commensurately, which is hard once deposit rates are at floored levels.

Secondly, competition for deposits could intensify; smaller banks or new entrants might offer higher savings rates to steal deposits, forcing NWG to pay up for funds and eroding its cost advantage.

And thirdly, mortgage competition remains fierce. To win new loans, NWG might have to offer thinner spreads.

All this could drive NIM down faster or further than expected, hurting future earnings.

Risk #3. Digital Disruption & Fintech Competition

As mentioned, the rise of fintech and digital competitors poses a long-term threat. While challengers haven’t toppled the big banks yet, they are nibbling at the edges.

Customer expectations are rising. People increasingly expect seamless digital experiences. In my own case, the only reason I’ve set foot in a branch in recent years was to pick up USD cash for travel. If incumbents like NWG fail to keep pace, they risk losing the next generation of customers to more agile fintech platforms.

Moreover, tech giants or telecom firms could eventually foray into banking services (payments, wallets) and erode the banks’ fee income. NWG is investing in digitalization, but the landscape evolves quickly.

Risk #4. Regulatory and Political Overhang

Banks are heavily influenced by the regulatory and political environment. A few angles here:

The UK government may be out of the shareholder register now, but that doesn’t mean politics are irrelevant. Banks often become political footballs. We saw this when the CEO was pressured by politicians in the Farage account controversy, and when parliamentarians called out banks for not passing on rate increases to savers. There’s a risk of political intervention like pressure to lower fees, mandated support for certain customers, or public criticism that hurts the bank’s reputation.

The lingering public perception from the bailout era means NWG has to tread carefully; any sign of excessive profits at the expense of consumers could invite a windfall tax or stricter regulations. For instance, The UK operates a Bank Levy on the balance sheets of banks, in addition to a Bank Corporation Tax surcharge on profits above a set threshold. When first introduced in 2016, the bank surcharge was 8% on profit above the allowance, paid on top of standard corporation tax and alongside the Bank Levy. The rules around these can change with government policy, impacting net earnings.

Conduct and legal risks: NWG, like others, has a history of past misconduct (e.g., mis-sold payment protection insurance/PPI). While the big PPI scandal is done, new issues can emerge such as the industry-wide motor finance mis-selling that hit Lloyds.

Verdict: Time to Reallocate

To wrap up, NatWest Group is a great bank that has largely achieved its turnaround, but the stock’s valuation now fully reflects its fundamentals. I’m proud of the gains we made in this position and still respect the company. The company is posting high-teens returns, paying fat dividends, and running a solid operation.

However, the easy money has been made. The stock’s upside from here looks limited, and there are headwinds on the horizon (margin compression, normalization of credit costs, etc.) that could cap further performance.

Sometimes the hardest thing is to sell a good company and NWG is a good company. But our goal is to beat the market by rotating into the best risk-reward opportunities at any given time. With NWG approaching my $19.25 fair value estimate, I see better uses for this capital.

As always, I’ll keep monitoring NatWest and the broader banking sector. If things change or a better entry emerges, I can reconsider. But for now, it’s farewell to NatWest; a stock that has surfed the wave to shore, and we’re stepping off to catch the next wave elsewhere.

Solid takedown of the risk/reward here. The structural hedge analysis is something most retail coverage misses, and realizing those hedges roll off gradually rather than all at once totally changes the NIM outlook. I've held some UK financials too and the exit discipline on a 42% gain shows what value investing should look like - taking profits when valuaation normallizes instead of hoping for another leg up.