Deep Dive GSL: Great Operator, Tough Industry: Why I’m Still Not Buying GSL

GSL’s management executed flawlessly, but mid-cycle economics and industry headwinds keep me on the sidelines.

Important note: This is an analysis of a company I ultimately did not add to the portfolio. My paid subscribers get access to the deep dives on the high-conviction, high-reward picks that do make it in.

Normally, I only publish deep dives on companies that are either already in the portfolio or being exited (as post-mortems). This one is different. I’m sharing it because Global Ship Lease is, in many ways, the kind of company I want to own. The management team has executed extremely well: they bought counter-cyclically in 2021, locked in long multi-year charters at peak rates, deleveraged aggressively, refinanced high-cost debt, hedged interest rates at the right moment, and kept shareholder dilution essentially at zero. On almost every controllable metric, they did the right thing.

The problem is that even excellent management can’t offset the cycle they’re sailing into. The containership industry is heading into a multi-year period of oversupply, shrinking charter rates, and likely mid-cycle returns that drift toward (or even below) the cost of capital. My work suggests the company won’t go bankrupt when rates fall; GSL will survive. But “survive” is not the same as “strong risk-adjusted return.”

In the bullish scenario, I see the shares worth roughly book value ($48).

In the base scenario, I get to around $25.

And in the bearish scenario, the equity value sits somewhere in the mid-$10s.

That range simply doesn’t give me the kind of skew I need to add the stock to our portfolio. So this deep dive is here not as a buy recommendation, but as a case study in disciplined process: sometimes the company is great, management is great, and the numbers are great…and you still pass.

Enjoy the deep dive!

TLDR

Global Ship Lease (GSL) is a well-run containership lessor with locked-in contracts, low leverage and a capable management team; the problem is the cycle.

Today’s earnings and dividend are flattered by legacy 2021–2022 charters. My updated work, which assumes day rates normalize around $20k per day and ROIC drifts toward or below a cost of capital, gives a central value of roughly $25 per share versus a stock price of $35.

A Monte Carlo simulation shows a wide range of outcomes, with a heavy left tail and about three quarters of scenarios below today’s price. So I like the business, but at this point I am passing rather than buying and will keep GSL on the watchlist for a better entry or clearer mid-cycle economics.

Table of Contents:

Company History and Evolution

Global Ship Lease’s journey began in 2007 as a Marshall Islands company formed to buy and charter out 17 container vessels from French liner giant CMA CGM. In August 2008, GSL went public via a SPAC merger (Marathon Acquisition Corp.), just as the global financial crisis struck. The timing was unfortunate as the 2008 crash triggered a prolonged shipping downturn that hit GSL’s original business hard. CMA CGM itself nearly went bankrupt in 2009, and GSL had to restructure charter agreements, struggling through the early 2010s as vessel values and rates collapsed. For roughly a decade, GSL’s growth stalled and its equity languished amid industry overcapacity and tepid trade growth.

A turning point came in late 2018. GSL executed a “transformative” merger with Poseidon Containers, acquiring 20 vessels (one was immediately sold) in November 2018. This Poseidon Transaction dramatically expanded GSL’s fleet and shareholder base (Poseidon’s owners took GSL shares) and set the stage for further growth. Under the leadership of Executive Chairman George Giouroukos and (former) CEO Ian Webber, GSL pivoted to an opportunistic acquisition strategy. In 2021, amid rock-bottom vessel prices, GSL purchased 23 additional ships. It wasn’t done: in late 2024, GSL agreed to buy four more modern eco-design ships (9,000 TEU size, high reefer capacity) for $274 million, with attached multi-year charters. By early 2025, GSL had also sold a few older, small ships (built 2000–2003) to keep its fleet younger.

As of March 2025, GSL owns 70 containerships ranging from 2,200 TEU feeders to 11,000 TEU post-panamax vessels. These are mid-sized and smaller containerships, often in niche trades or secondary routes. Notably, 39 of the ships are wide-beam post-panamax designs (optimized for the new Panama Canal). In total, GSL’s fleet capacity is 404,681 TEU with a weighted average age around 15 years.

From its CMA CGM-centric origins (all original ships were on charter to CMA CGM), GSL has evolved into a diversified tonnage provider serving multiple top-tier liner companies. Major charter clients in recent years include CMA CGM, Maersk, MSC, Hapag-Lloyd, OOCL, ZIM, and SeaLead, among others. This diversification reduces counterparty risk, and GSL generally focuses on “reputable container shipping companies” as charterers.

In summary, GSL’s history reflects the boom-bust cycles of container shipping. It survived the 2008-2018 lean years through restructuring, then positioned itself to thrive when the cycle turned. The 2020-2022 Covid shipping boom was that moment and GSL locked in lucrative long-term contracts and used the cash windfall to strengthen its balance sheet (more on that later). Today, the company stands on a much stronger footing, with a larger fleet and high contract cover, poised to navigate whatever the next cycle brings.

Business Model and Unit Economics

GSL’s business model is straightforward: it owns container vessels and rents them out under fixed-rate time charters, typically for multi-year terms. In essence, GSL is a landlord of ships, leasing vessels to liner operators for agreed daily rates. The liners (charterers) handle voyage operations, pay for fuel (except when ships are idle), and bear cargo risk. GSL just provides the asset and crewing/maintenance.

This model generates steady, predictable revenue so long as charters are in place. It’s akin to a real estate company with tenants on long leases, except the “buildings” are ships floating on the high seas.

Crucially, GSL avoids exposure to volatile spot freight rates. Whether container shipping rates soar or crash, GSL’s charter income stays constant during the contract term. As of mid-2025, GSL’s entire fleet was employed on fixed charters, no ships in the spot market. This leads to excellent forward visibility.

In fact, lessor companies like GSL typically have 80–85% of the next 12 months’ vessel days already fixed by the start of the year. Management recently noted that due to strong charter coverage, GSL’s near-to-medium-term cash flows are “highly predictable and visible.”

We can quantify GSL’s charter coverage. At June 30, 2025, the minimum contracted future revenue was $1.612 billion (net of commissions) through charter expirations into 2029. For context, that backlog is over 2x GSL’s 2024 revenue. In weighted terms, it represents about 2.3 years of revenue cover on average. In other words, GSL has essentially pre-sold over two years’ worth of ship rent. Breaking it down, $702 million of charter revenue is secured through mid-2026, $542 million through mid-2027, and $266 million through mid-2028. Even by mid-2029, some $8.5 million of revenue is still under contract. This staggered expiry schedule means only a modest portion of GSL’s fleet comes off charter in any given year, giving management flexibility to time vessel re-chartering or sales. The backlog is a vital shock absorber: even if the market hits a rough patch over the next 1–2 years, GSL can ride it out on existing contracts while planning fleet adjustments.

Let’s talk unit economics. GSL’s costs to operate a ship (crew, maintenance, insurance, etc.) run about $8k–$9k per day, and depreciation/amortization adds roughly $4k/day. So, all-in cash and non-cash operating costs might be ~$12k–$13k per ship per day. What charter rate does GSL need to earn a decent return above that? If we assume a 10% unlevered return on a ship’s value, GSL might need roughly $21k–$22k/day in charter hire. Currently, however, GSL’s charters are far above that. During the Covid supply chain frenzy, liners were desperate for capacity and agreed to very high charter rates. GSL locked in many multi-year charters at rates around $30k/day (or higher), well above the long-run “mid-cycle” levels. At $30k/day, the company’s cash breakeven is easily covered, producing operating profit margins on those ships of ~50%+ and ROEs near 30%.

In essence, GSL is temporarily earning supernormal returns because many of its charters were locked in during the tight 2021–22 market. Management knows these excess returns won’t last. What matters is what the business looks like once rates normalize. If day rates fall from the recent ~$30,000 per day to something closer to $20,000, the economics change a lot. On GSL’s historical vessel cost basis (roughly $35 million per ship), I estimate unlevered ROIC of 9–11%. On newer eco-vessel prices closer to $60–70 million, ROIC could fall to 5–6%, which dips below most estimates of the industry’s cost of capital. That is the sober version of the future, and I build my valuation around that lower return environment.

The key point is this: once rates settle at more normal levels, I see ROIC drifting below the cost of capital. That kind of return profile explains why the stock trades where it does today and limits the upside.

It’s also worth noting GSL’s charter strategy. The company focuses on securing forward cover before acquiring ships. It does not speculate by ordering brand-new ships without contracts. Instead, GSL typically buys second hand vessels only when it can tie the purchase to an attractive charter. This was evident in 2021–22: GSL snapped up older ships at low prices but with charters attached at high rates, effectively locking in immediate positive cashflow.

This disciplined approach means GSL isn’t betting on what the market will be in 2–3 years (unlike peers that ordered expensive newbuilds for future delivery). GSL’s fleet is 100% chartered (no idle ships) and generally 100% cashflow-positive, ships without charters are sold or scrapped.

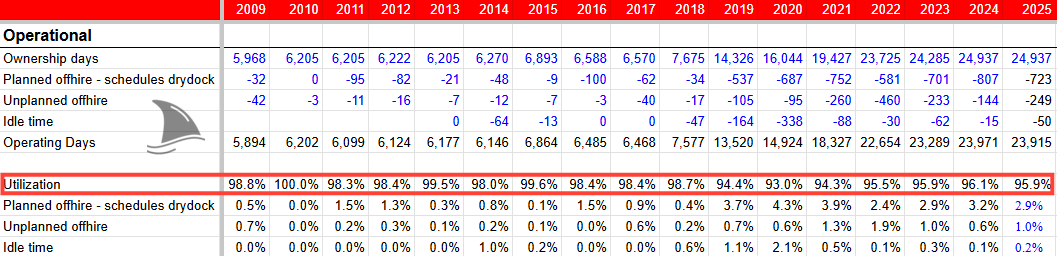

Management calls this a “forward fixing” strategy: extend or renew charters well in advance, to minimize downtime. The payoff is evident in GSL’s utilization: historically in the high 90% range (96.1% in 2024). Essentially, GSL keeps its ships busy and earning, like a landlord keeping properties rented.

Industry Landscape: Cycles, Shifts, and Storm Clouds

To appreciate GSL’s prospects, we need to understand the container shipping industry’s recent past and current dynamics. It has been a wild ride. After the 2007–08 shipping bubble and global financial crisis, the industry spent a decade in a down-cycle. Ship owners had overordered new vessels in the mid-2000s boom, leading to chronic oversupply. Trade volumes grew sluggishly after 2010 due to slower GDP growth and some protectionist trends, breaking the previously high correlation between container trade and global GDP. Excess capacity and tepid demand meant low freight rates throughout the 2010s; many ship owners went bankrupt or survived on slim margins. GSL itself wrote down asset values and saw poor returns in that era.

COVID-19 dramatically flipped the script. The pandemic initially crashed trade volumes in early 2020, but by late 2020 and into 2021 a combination of stimulus-fueled consumer demand and supply chain disruptions ignited an unprecedented container shipping boom. Freight rates skyrocketed to record highs. Liner operators (e.g. Maersk, CMA CGM, etc.) reaped windfall profits, and a chunk of those profits flowed through to charter owners like GSL. Charter rates for ships jumped 5–10x from their trough. Critically, carriers were so profitable that they agreed to enter into contracts with lessors like GSL for high charter rates because the high charter rates were peanuts compared to the freight rates they were earning.

In other words, a liner like CMA CGM might be earning $200,000 per day on a ship in spot freight revenue, so they didn’t mind paying $30,000/day to charter a vessel, a trivial cost given their margins. GSL seized this moment to lock in multi-year charters at historically high rates. The liners were willing to sign 3–5 year charters at elevated levels because they badly needed ships to move cargo and had cash to burn. These charters typically have to be honored irrespective of what happens to freight rates (short of the charterer going bankrupt, which in this cycle is unlikely since most liners amassed huge cash reserves).

The Covid boom peaked in late 2021/early 2022. Since then, the party has ended for container shipping. As expected, record profits spurred a massive wave of new ship orders. Global carriers went on an ordering spree in 2021–22, splurging on the latest mega-vessels (15,000–24,000 TEU leviathans) as well as many smaller ships.

According to industry data, the container ship orderbook climbed to record highs by 2023–24.

By August 2025, the orderbook stood at around 10 million TEU or about 31% of the global fleet’s capacity. This is the largest orderbook relative to fleet since 2010, and comparable to the mid-2000s boom that led to the last glut. In short, a ton of new capacity is on the way. Deliveries started accelerating in late 2023 and will peak around 2024–2025, with another surge in 2028 (from orders placed in 2023).

Analysts forecast the global fleet will grow 6% per year from 2025 to 2028 far above expected demand growth of only ~2–3% per year. For instance, container demand is projected up just 2.6% in 2025 (in line with IMF global GDP forecasts), and a mere 1.7% in 2026. This structural oversupply could persist well into the latter half of the decade, absent some mitigating factor.

For much of 2023–24, one mitigating factor did exist: the “Red Sea crisis.” During the Yemen conflict and related regional tensions, certain Red Sea and Suez Canal routes were deemed risky. Starting in late 2023, many ships began detouring around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope instead of transiting the Red Sea/Suez, due to Houthi rebel threats and other security issues.

These longer routes significantly increased voyage distances and absorbed a lot of shipping capacity. For example, in 2024 the global container fleet grew 10%, but much of that was soaked up by longer Asia-Europe voyages via the Cape. Alphaliner estimated that diversions around the Cape effectively tied up the equivalent of 1.76 million TEU of capacity (59% of 2024 fleet growth) that would otherwise be idle. Idle tonnage fell to near-record lows (<1% of fleet idle) despite all the new ships delivering. In essence, the Red Sea/Suez disruptions postponed the overcapacity day of reckoning.

However, a ceasefire in the Yemen conflict and diplomatic efforts have raised the likelihood that normal Red Sea passage will resume. When that happens (as early as 2024–25), ships will revert to shorter routes, freeing up a huge chunk of effective capacity virtually overnight. In other words, the industry could face a double whammy: a flood of new ships plus the equivalent of a large chunk of the fleet re-entering service as voyages normalize. Carriers have already started to prepare: we are seeing increased ship idling, slow-steaming, and blank sailings (canceled voyages) as they try to absorb the glut. But such measures can only do so much to offset a structural surplus.

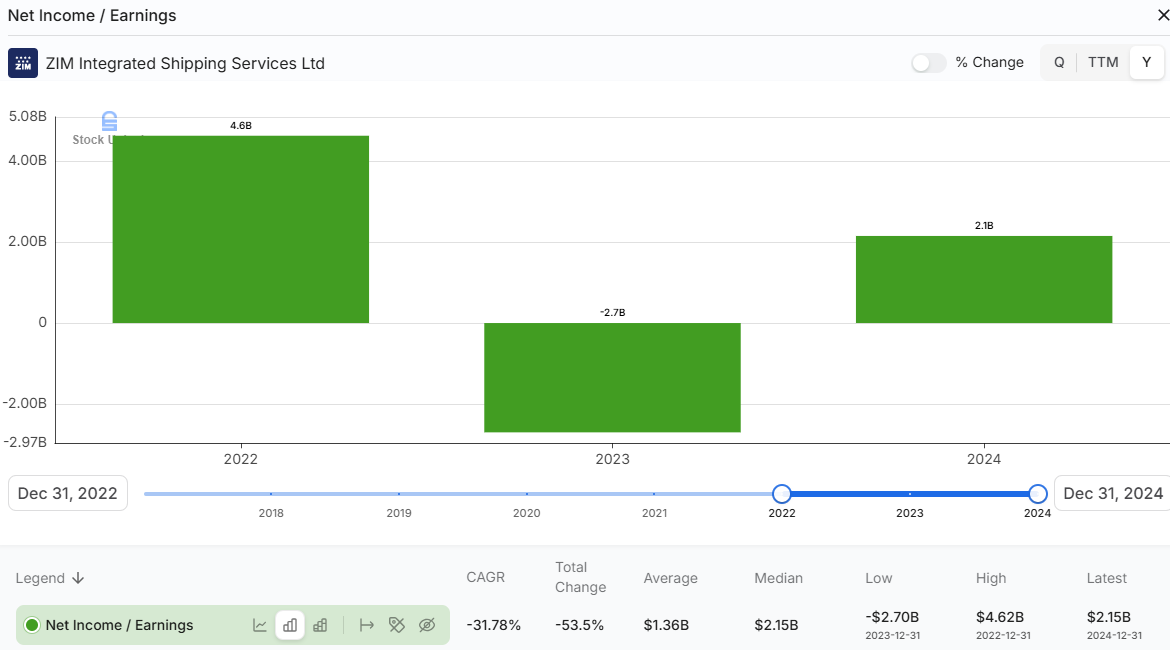

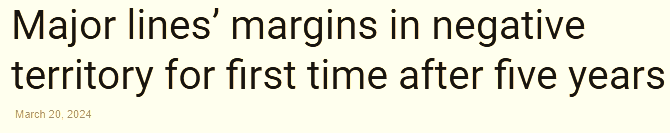

The current headwinds in the industry, therefore, are significant. Freight rates have plummeted from their 2021 highs back to (or below) pre-pandemic levels on many routes. Profitability for liner companies has collapsed. To illustrate, by late 2023 the mainline operators’ average operating margins turned negative for the first time in five years.

In Q4 2023, six of the nine largest container lines reported operating losses — a stark reversal from the boom years. Looking forward, by Q1 2025 the average operating margin among the major carriers had already slipped to 18.1%, and by Q2 it dropped further to 9.9%, the lowest in 18 months.

This demonstrates the cycle is no longer just turning and it’s tilted into the down-side.

Beyond supply glut concerns, there are structural shifts and geopolitical factors at play. Globalization is no longer accelerating as it once was; there are trends of reshoring and regionalization (e.g. US importing more from Mexico, Southeast Asia instead of China). Trade disputes and tariffs also loom. The U.S.-China trade war, for example, is ongoing and tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of goods remain, dampening the growth of Transpacific volumes.

The U.S. is even introducing new port fees on carriers using Chinese-built ships, which could raise costs. Geopolitical flashpoints (Russia-Ukraine war, Taiwan tensions, etc.) add uncertainty to trade flows. Furthermore, environmental regulations like IMO 2023 are forcing ships to slow steam or retrofit for emissions compliance, which can reduce effective capacity but also add costs. Even climate events (drought at the Panama Canal causing transit restrictions, etc.) have recently affected shipping routes.

One positive structural change is industry consolidation: today the top 10 liner companies control about 80% of global container capacity (versus maybe 50–60% two decades ago). This oligopoly has resulted in more rational behavior (until 2020, liners showed discipline in capacity management, avoiding ruinous price wars). It also means the charter counterparty risk for GSL is mostly with large, well-capitalized firms rather than a multitude of small, weak players. The downside is these mega-liners have more bargaining power and can form vessel-sharing alliances to optimize capacity usage, which might reduce their need for chartered tonnage at the margin. Still, many liners prefer an asset-light model even after the recent buying spree, roughly half of the global fleet is still chartered in rather than owned. Charter owners like GSL serve a crucial role providing flexible capacity.

Where are we now in the cycle? The container industry remains under pressure despite pockets of good news. Global container volumes are up about 4–5% in early 2025 (126.75 million TEUs through August, a 4.4% increase vs same period in 2024).

That said, freight rates remain under significant strain and new capacity is still hitting the water. According to industry data, the order-book remains well above 30% of existing fleet capacity, signalling a structural risk of oversupply. Carriers such as CMA CGM have already flagged weaker profit outlooks going into 2026 because of an imbalance between supply and demand. The view now is that 2025 and 2026 will be challenging years where earnings for many shipping companies will be compressed even if outright negative outcomes are avoided.

So there is hope the market could find equilibrium in a few years, especially if older ships are scrapped aggressively. Also, macroeconomic conditions will play a big role: container trade is still linked to GDP/trade growth. If a global recession hits, volumes could contract, worsening the glut. Conversely, a surprising economic boom or stimulus (e.g. China ramping infrastructure) could absorb some slack.

For GSL, this backdrop presents both risks and opportunities (explored more in the Risk section). The key takeaway is that we are in a very different part of the cycle than when GSL locked in its current charters. Back in 2021, it was a tight market favoring ship owners; now it’s a loose market favoring charterers. Charter rates for feeder and mid-size ships have fallen dramatically since early 2022. For example, a 5,000 TEU ship that might have fetched $40k/day on a 3-year charter in mid-2021 might get under $20k/day today on a short term fixture (if that). Many smaller/older ships are even finding no employment and heading to scrap yards. Asset values for ships have likewise declined from their peak; however, they are still above pre-Covid levels in many cases (helped by scrap steel prices and the fact that newbuild prices are high due to full shipyard orderbooks). GSL has noted that ships sold recently (by them and peers) have mostly been at a gain to book values, indicating its book might even be conservative on vessel valuations.

In summary, the container shipping industry is facing a tough period of oversupply and weak rates in the mid-2020s, after an extraordinary boom. Any long case on GSL hinges on its contract protection and prudent management to get through that storm, not on the industry dodging a downturn. My work now suggests that while GSL should survive the cycle in good shape, the returns that follow are likely below the cost of capital than to the supernormal period of 2021–2024.

Competitive Positioning and Peers

GSL operates in the containership charter owner segment, where its primary peers include companies like Danaos Corporation (DAC), Costamare (CMRE), Atlas Corp/Seaspan (private), Navios Partners (NMM), and a few others (smaller players like Euroseas, MPC Container Ships, etc.). Among these, Danaos and Costamare are the most directly comparable public peers.

In terms of fleet size, GSL’s 70 ships (405k TEU) put it in the middle of the pack. Danaos has around 68 containerships (421k TEU) and Costamare around 77 container ships (581k TEU) plus a fleet of dry bulk vessels. Seaspan (Atlas) was larger (1.0M TEU) but was taken private in 2023. GSL focuses on mid-size and smaller vessels (2,000–11,000 TEU), whereas Costamare and Danaos also have some larger +13,000 TEU ships. The mid-size segment that GSL plays in is interesting as many global trades (intra-Asia, feeder routes, secondary hubs) rely on ships in the 2k–10k TEU range. This segment has seen less newbuild ordering relative to the megaships, meaning the supply overhang could be somewhat less severe for mid-sizers.

GSL’s CEO has highlighted that their fleet is oriented towards “workhorse” ships that are critical to certain routes (for example, wide-beam 8,500 TEU ships that can’t be easily replaced on certain lanes due to port depth or bridge restrictions).

From a contract profile perspective, GSL is second to none. Its charter backlog ($1.6B) equates to ~2.3 years of revenue coverage, which is similar or better than Danaos and Costamare. All three companies took advantage of the boom to lock-in multi-year charters. For instance, Danaos in mid-2021 fixed some ships on extraordinary +7 year charters at high rates. Costamare likewise has many ships chartered into 2025–27. So charter cover is high across the peer group.

One differentiator: GSL has no orderbook of its own (no newbuilds on order). Danaos, on the other hand, decided to order several newbuild ships in 2022 for delivery 2024–25. Those will consume capital and add risk (as the ships will deliver into a weak market). GSL’s strategy of buying only second hand with attached charters seems wiser in hindsight as it is not adding uncontracted capacity into an oversupplied market. Costamare did not order container newbuilds recently either (though it expanded into dry bulk ships, which GSL has not). Overall, GSL’s asset allocation discipline stands out: they have only grown when accretive charters were available, and they are not “empire-building” for its own sake.

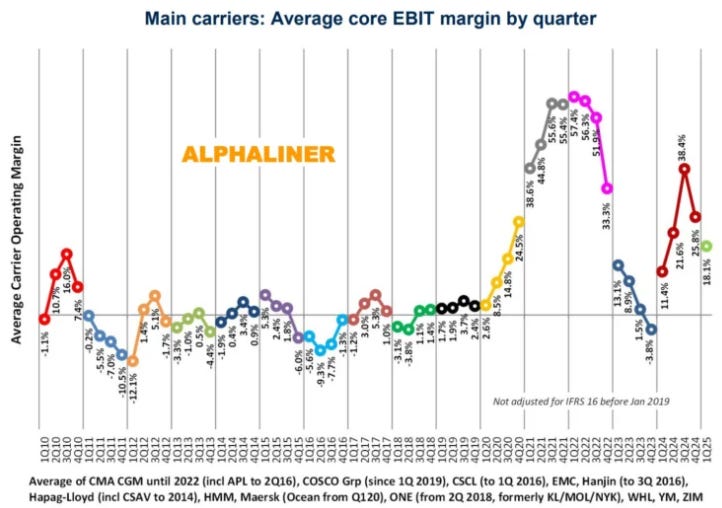

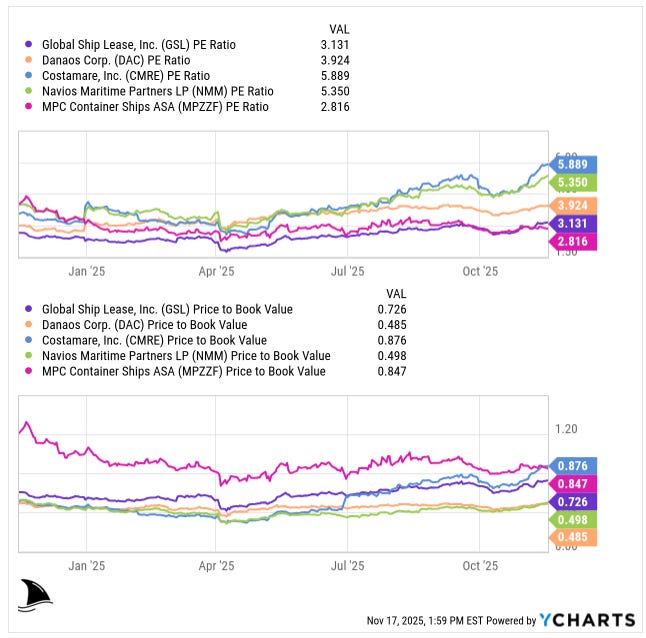

GSL trades at P/E 3.13x and P/B 0.73x, which puts it in the cheap cluster on both metrics but not the absolute cheapest. Danaos screens cheaper on book at 0.49x and slightly higher on earnings at 3.92x. Navios Partners also trades below book at 0.50x, with a higher P/E of 5.35x. Costamare sits above both at P/E 5.89x and P/B 0.88x. MPC is the outlier at P/E 2.82x, the lowest in the group, but trades richer than GSL on P/B at 0.85x. In short, GSL is inexpensive on earnings relative to peers and still trades well under book, even if Danaos and Navios carry a deeper book discount.

In absolute terms, these lessors are still priced as if future earnings will fade. The dividend yields reflect that caution. GSL sits at 5.60%, which is toward the high end of the mainstream peer group. Danaos pays 3.58%. Costamare pays 2.72%. Navios Partners is far lower at 0.37% given its reinvestment-heavy model. MPC Container Ships screens at 19.13%, which is an outlier driven by its payout formula rather than a sustainable underlying yield. Net: GSL offers one of the richer, more sustainable yields among the established operators.

It appears investors assign GSL a slight discount, perhaps due to its smaller size or higher leverage historically. However, as we’ll discuss in the next section, GSL’s leverage has come down dramatically, removing what used to be a relative weakness.

One nuanced difference: charter mix and counterparties. GSL historically had a lot of exposure to CMA CGM (which at one point accounted for the majority of its revenue). After the Poseidon merger and subsequent deals, GSL’s exposure is more spread out. Its biggest customer is now likely CMA CGM or MSC, but it charters to at least 8 different liners.

Danaos has significant charters with ZIM (including some very high-rate charters that ZIM locked in, which some fear could be renegotiation risk if ZIM’s troubles persist). Costamare’s charters are mostly with top-tier liners (MSC, Maersk, etc.) and it even has some joint ventures in the liner space (it co-owns ships with charterers). Overall, charterer default risk seems low in the near term as the major liners are flush with cash from the boom (even after recent losses, most have huge war chests). So on that front, GSL and peers should all collect their contracted revenues without much worry right now.

Another aspect of competitive positioning is capital allocation and strategy. GSL’s management has shown a shareholder-friendly streak, which we’ll cover more below (dividends, buybacks, deleveraging). Danaos has also paid dividends and did buybacks (and once a special dividend from selling ZIM shares). Costamare historically was a steady dividend payer (though it cut during COVID briefly).

One could argue GSL, being smaller, has more room to grow (it’s easier to double in size from 70 ships than for a larger peer). Indeed, GSL has been active in M&A and could continue to play consolidator if opportunities arise. The charter owner space is fragmented into dozens of independent owners, many of which are financially strained in downturns. GSL with its stronger balance sheet might be able to pick up additional ships at distressed prices during this downturn (just as it did in 2018 and 2020). This optionality could let GSL grow NAV per share even if the industry is struggling, by buying low and later benefiting when rates recover.

None of the charter ship lessors get much love from Mr. Market. They all trade at deep value levels due to the cyclical nature of shipping. However, I’d argue GSL is among the most misunderstood. One reason is its name and sector. Many investors lump GSL in with the container liner stocks or with shipping stocks at large, assuming its earnings will crash alongside spot freight rates. They see news of “container shipping profits plummet” and assume GSL must be hurting too, which is not true (GSL’s earnings in 2024 is actually at record highs thanks to fixed charters).

Danaos and Costamare might be slightly better known or have longer track records with Wall Street. GSL is a bit under-the-radar and perhaps still proving itself after earlier struggles. That information gap can cut both ways; it might allow a re-rating if the post-boom economics prove better than feared, but it also means investors may be slow to notice if returns settle below the cost of capital, which is my base case today.

Dividend Policy: Rewards and Inconsistency

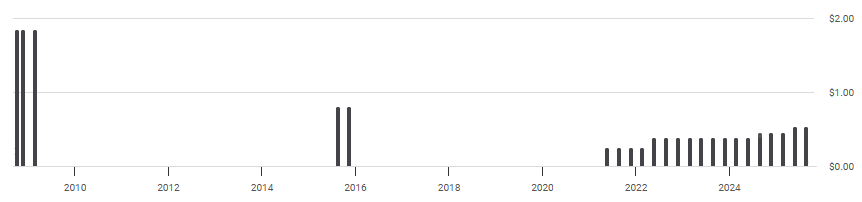

One of the attractions of GSL is its hefty dividend yield. But GSL’s dividend history has been anything but steady in the long run.

It’s important to understand how the company’s dividend policy has evolved and why I view the current payout as both sustainable in the near term and variable in the longer term.

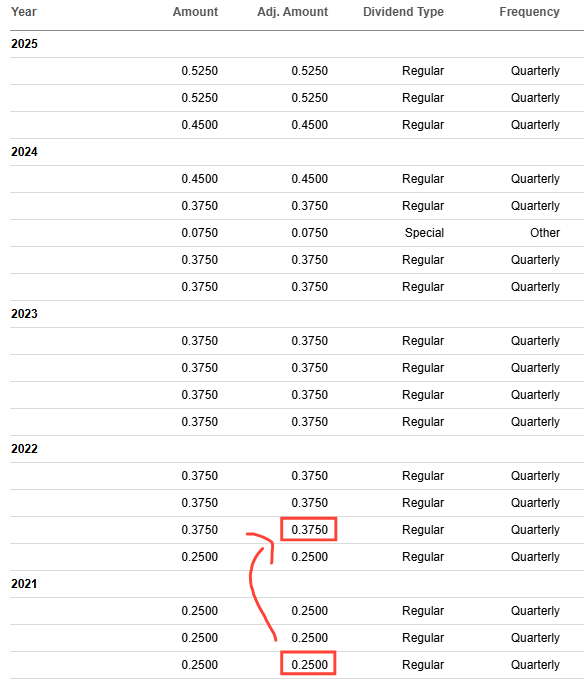

Originally, back at the IPO in 2008, GSL intended to pay regular dividends (as many shipping companies did). However, the post-2008 industry collapse led to GSL suspending dividends for many years while it restructured. No dividends were paid for roughly a decade. Fast forward to 2020: after the Poseidon merger and with the company stabilizing, GSL announced in early 2021 that it would reinstate a quarterly dividend.

The initial indicated rate was a modest $0.12 per share quarterly. But given how strong the market turned out in 2021, GSL’s board actually paid $0.25 per share each quarter in 2021. Essentially doubling the payout from the initial plan, thanks to surging cash flows. Then in November 2021, management announced the quarterly dividend would increase by 50% to $0.375 starting in Q1 2022.

Through 2022 and all of 2023, GSL paid $0.375 per share each quarter. This was a generous payout (annualized $1.50), but by late 2023 the company was flush with cash and earnings still rising, so they decided to bump it up again. In August 2024, the board declared a 20% increase to $0.45 per quarter (effective Q2 2024 onward). Thus, for Q2, Q3, Q4 2024, GSL shareholders got $0.45 each quarter (annualized $1.80). Not stopping there, in March 2025 GSL announced yet another raise: an additional $0.075 “supplemental” on top of the $0.45, bringing the total to $0.525 per quarter starting Q1 2025. This 16.7% hike reflected management’s confidence in near-term cash flows. So currently, $0.525 quarterly equals $2.10 annualized which at the stock’s $31 price is about a 6.8% yield.

It’s worth noting that management has characterized part of the dividend as “regular” and part as “supplemental.” Essentially, they view $0.375 (the 2022–2023 level) as a base quarterly dividend, and the portion above that (now $0.15 extra per quarter) as a temporary supplement while cash flows are unusually high. The reason: they know the current earnings are elevated due to those above-market charters, so they’re returning some of that windfall directly to shareholders but not necessarily committing to it permanently. This approach gives them flexibility to reduce the dividend later without technically “cutting” the base dividend as they could just not declare the supplemental portion if conditions worsen. In practice, of course, if the downturn is severe, the total dividend could indeed be reduced. Management has explicitly said future dividends will be at the Board’s discretion and depend on cash flow, leverage, opportunities, etc.. So we should not take $2.10/year as sacrosanct forever. It is likely safe through 2025 given the charter coverage, but beyond that, if a lot of charters roll off into lower rates, the payout may be adjusted.

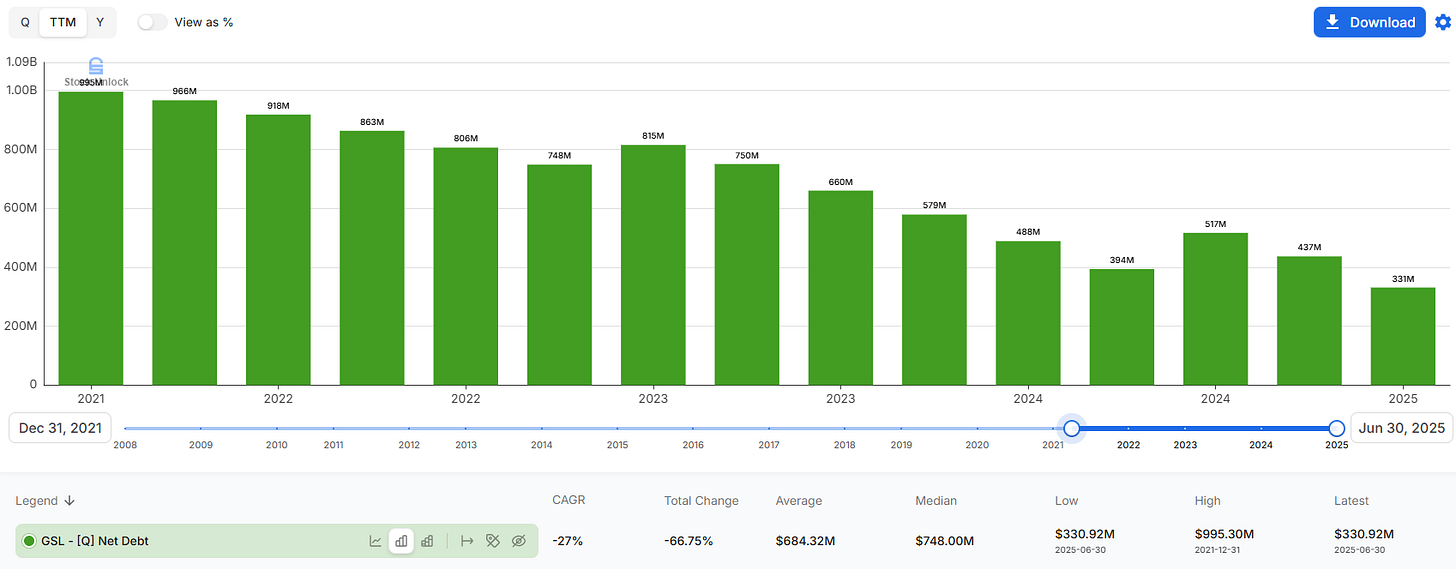

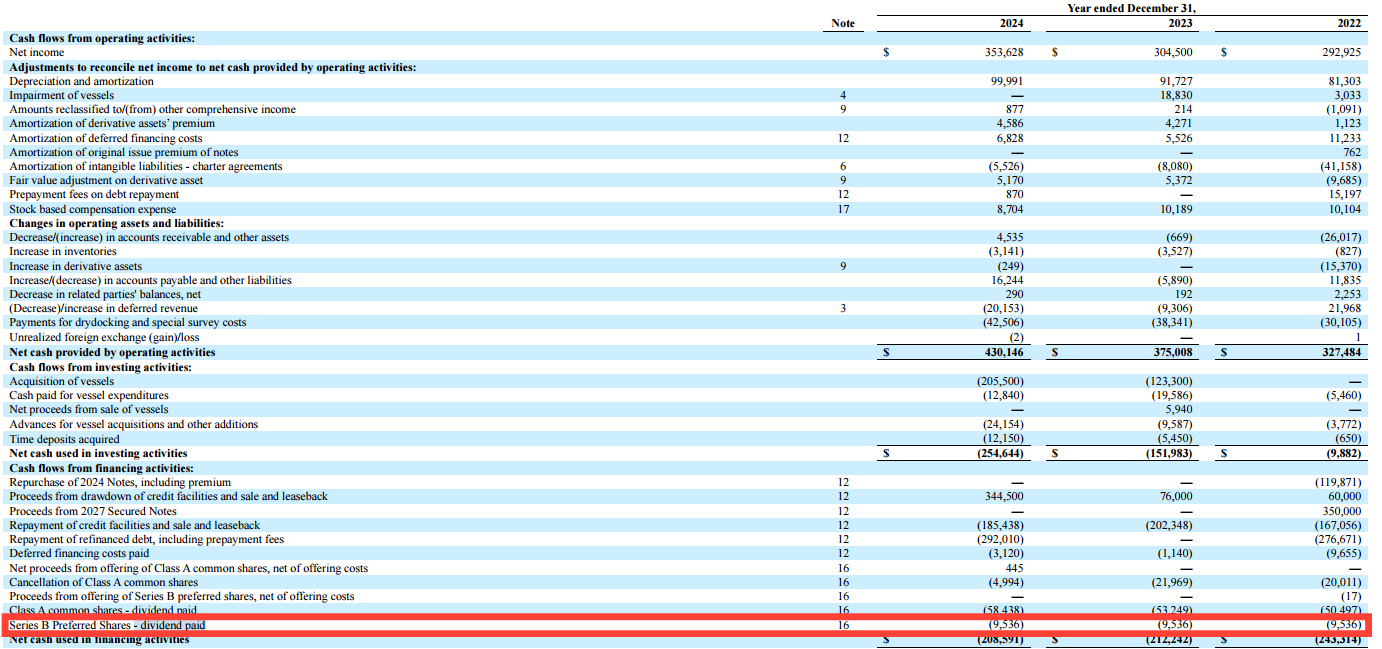

What I do find encouraging is that even while raising dividends, GSL has significantly deleveraged.

Many shipping companies either over-distribute and neglect the balance sheet (setting up for pain later), or hoard cash and never reward shareholders. GSL is threading the needle: it returned cash and improved its financial resilience. From early 2021 through mid-2025, GSL’s net debt plunged from over $995 million to about $331 million. That’s an extraordinary turnaround partly due to EBITDA surging, but also due to management actively using cash to repay debt. They did this while still paying those rising dividends.

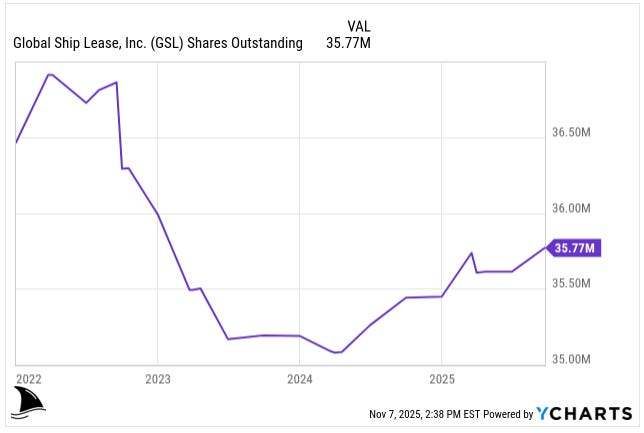

In addition, the Board authorized share repurchases: in 2022 GSL bought back $20M of stock (at ~$18.87 average), and in 2023 another ~$22M (at ~$17.68).

Those were accretive buybacks at half of book value, essentially a no-brainer use of capital. A further $5M of buybacks were done in early 2024, and $33M authorization remained as of the 2024 annual report.

This track record gives me confidence in management’s capital allocation acumen. They increased the dividend when it made sense (lots of excess cash), but also diverted cash to the highest-return uses (debt reduction and buybacks at deep value). The dividend, while “inconsistent” if you look over 15 years, has been consistently growing in the last 4 years.

One might say the dividend was inconsistent in the past because the business was struggling; now that the business is strong, they’ve been quite consistent about paying and raising it. Of course, if we get a prolonged industry slump, I fully expect GSL to adjust the dividend accordingly (and they should be protecting the balance sheet).

For example, by 2026 if a lot of ships re-charter at much lower rates, the “supplemental” portion could be dropped, bringing the quarterly dividend back to $0.375 or $0.45. Even in that scenario, at today’s price the yield would be attractive (4.2%-5.1%). There’s also the possibility that management chooses to deploy cash into growth opportunities (e.g. snapping up distressed assets) instead of maximizing dividends, if the returns justify it.

One more note: GSL’s preferred shares (GSL-B), 8.75% preferred, have always been paid on schedule. The common dividend is junior to that, and by policy GSL cannot pay common dividends if preferred are in arrears. Preferred dividends are $9.5M per year. GSL has never missed those, and given the tiny size relative to cash flow, they’re not a concern.

Capital Allocation and Management Quality

GSL’s management has navigated the recent cycle exceptionally well, in my view. They’ve demonstrated a prudent balance of offensive and defensive moves by expanding the fleet at opportune moments, while simultaneously deleveraging and shoring up the balance sheet. This speaks to the quality of management and alignment with shareholders.

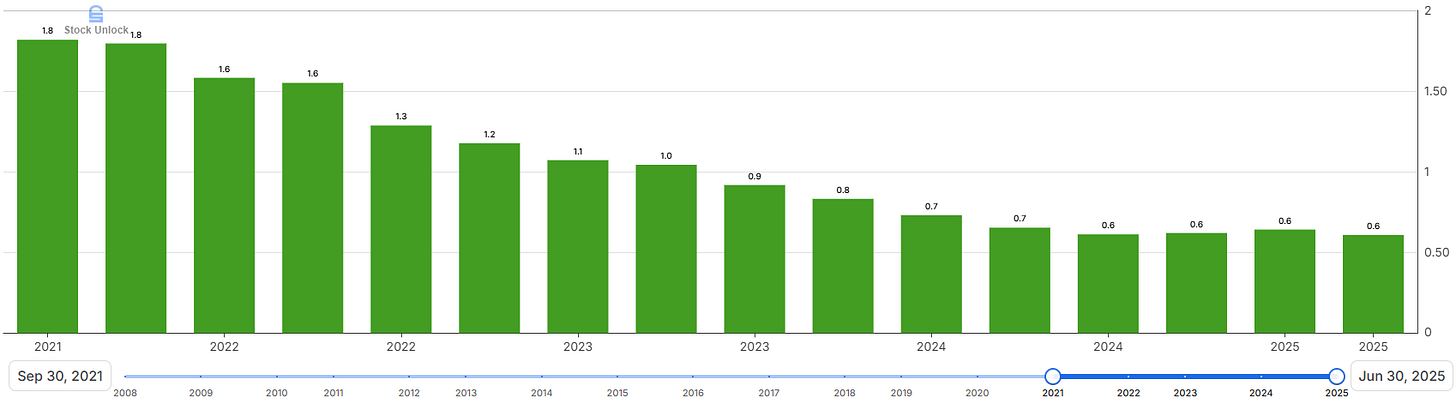

Let’s start with the deleveraging story, because it’s striking. In 2018, after the Poseidon merger, GSL had a mountain of debt. Again in 2020–21, when they acquired 23 vessels, they financed a chunk with debt. Net debt peaked around $995 million. Fast forward to mid-2025: net debt is down to $331 million or 0.7x TTM EBITDA.

To put it another way, debt-to-equity is now 0.6, whereas a few years ago it was 1.8. GSL has massively de-risked its balance sheet using the cash windfall of 2021–2023.

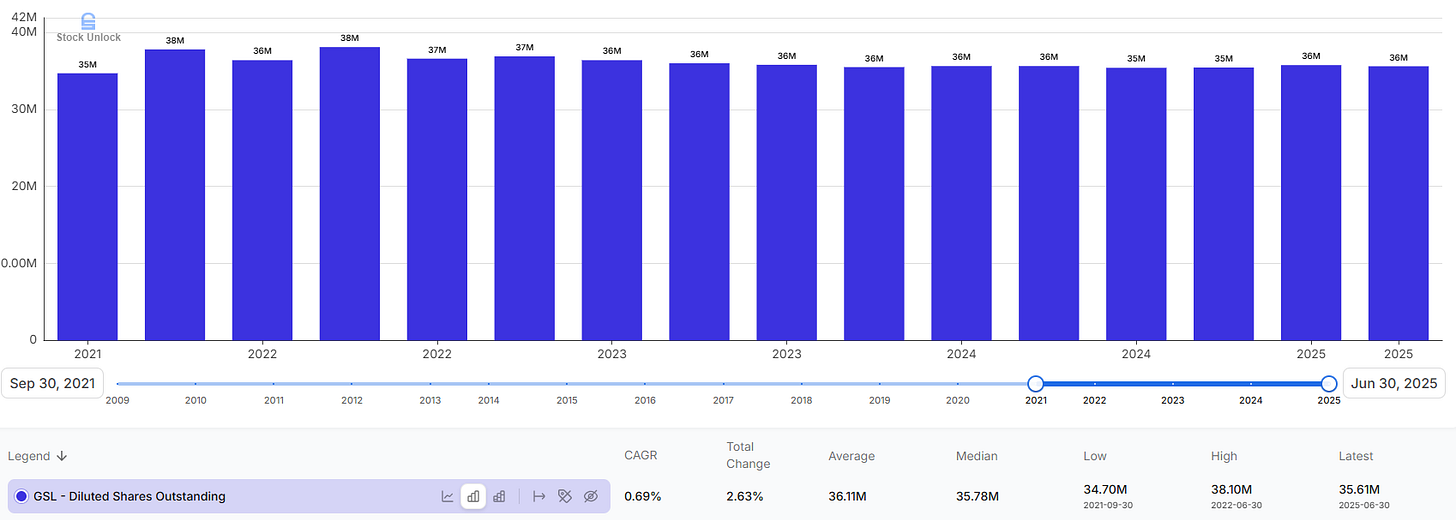

Notably, they achieved this without materially diluting common shareholders.

Many shipping companies in 2021, seeing high stock prices, issued equity. GSL did have an ATM (at-the-market equity program) but only sold a trivial amount ($27k shares in 2024). Instead, they let their cash flow do the work. They refinanced expensive bonds: GSL had an 8.0% unsecured note due 2024, which they redeemed early (in 2021) cleaning up their debt stack.

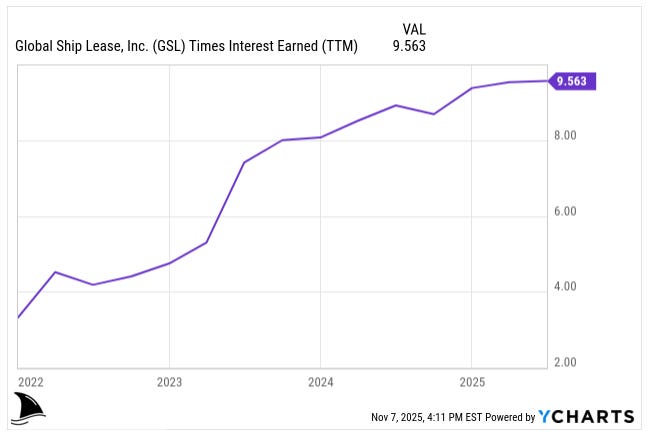

They also refinanced various secured facilities at lower rates. GSL smartly entered interest rate cap hedges in early 2022 when rates were still low, capping LIBOR on a large portion of debt at 0.75%. Those caps (SOFR ~64 bps effective) last until Q4 2026, meaning GSL is largely protected from interest rate spikes on most of its floating debt. As a result, even as rates rose, GSL’s interest expense decreased from $75.3M (2022) to $40.7M (2024) thanks to lower debt and hedging.

The company’s average cost of debt is now quite low (around 5% or less) and interest coverage is extremely high (EBIT/Interest 9.6x).

By paying down debt, GSL has also unlocked strategic flexibility. They have freed up collateral (several ships were released from mortgages as debt was repaid). As of Q3 2025, GSL even had $490 million of cash sitting on the balance sheet, a war chest to deploy if opportunities arise.

Management indicated that beyond required drydock and regulatory capex, they have no material commitments and will consider uses of cash such as fleet growth, debt repayment, share repurchases, or other investments. This optionality is valuable.

If the downturn drives second hand ship values way down, GSL could pounce and buy additional vessels cheaply (ideally with charters attached). If not, they can keep paying dividends or even retire more debt. The point is, they are not forced into any action as they have time and flexibility, which is a direct result of good capital management.

Management’s operational execution has also been solid. They keep vessel utilization high even during drydock-heavy years.

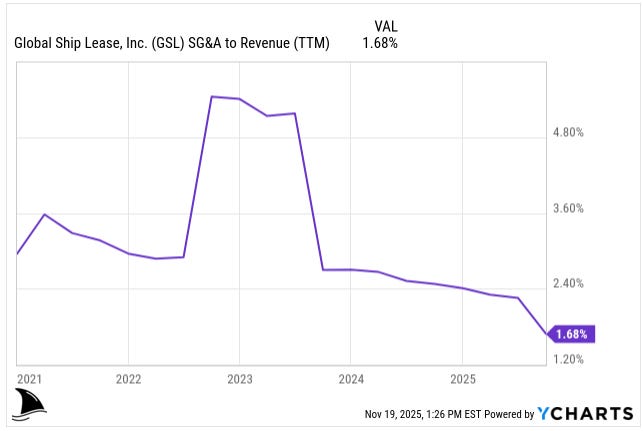

They have controlled operating costs reasonably. Vessel opex did rise 3.9% in 2024 to $7,670/day, due to crew wage increases and inflation, but that’s modest. GSL’s SG&A is very low.

Some of this is because they outsource technical management to Technomar (a related-party company of the Chairman) and commercial management to Conchart, paying fees rather than building a huge in-house team. Those fees (Technomar $21.8M in 2024, Conchart $8.6M) are arm’s-length and not excessive, as far as can be told. All in all, management runs a lean operation which is what you want in a commodity-like business.

On the strategic front, I like that GSL hasn’t chased diversification for its own sake. Some peers jumped into new sectors (Costamare into dry bulk, Navios mixes many segments, etc.), which can dilute focus.

GSL has stuck to what it knows and is reaping the benefits of that focus. They’ve also shown restraint on growth: during the boom when asset prices skyrocketed in 2022, GSL did not buy new ships at inflated prices. Danaos, in contrast, ordered new ships at high prices (which may or may not pay off). GSL waited until late 2024, when second hand prices had cooled a bit, to pick up those four eco 9,000 TEU ships with charters. And those came with multi-year charters from a top liner (the charters extend 1.7 years on average, likely at decent rates).

It appears GSL got a good deal: they paid $274M for four relatively new vessels (built 2015, high-spec). One can infer the attached charters cover a significant portion of that investment, de-risking the purchase. This is a pattern: earlier in 2021, GSL’s fleet expansion was heavily weighted to older ships that had charters covering their remaining useful lives or close to it, essentially self-amortizing deals.

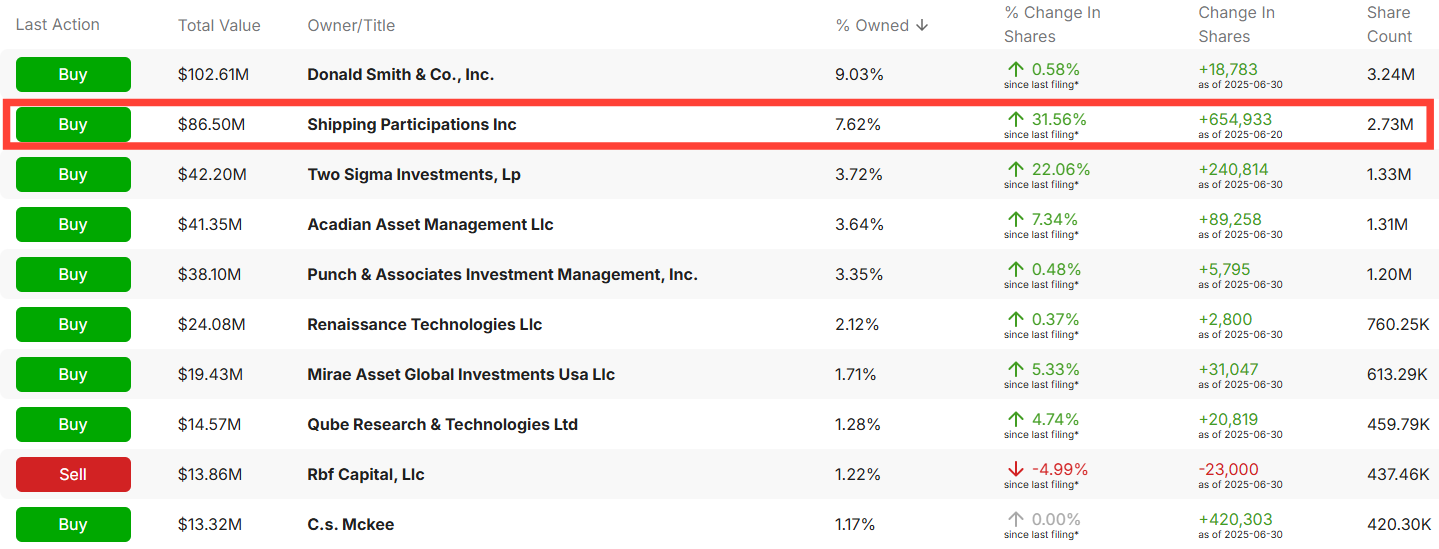

Management continuity and quality deserve mention. George Giouroukos, the Executive Chairman, effectively founded Poseidon and has deep shipping experience (since the 1990s). He and his affiliates own a sizable stake in GSL (through Shipping Participations Inc, Poseidon’s ownership roll-over).

The CEO as of 2023, Thomas Lister, was previously the Chief Commercial Officer and has been with GSL since 2007 so he knows the company inside out. The CFO, Anastasios Psaropoulos, has been with Technomar and GSL’s finance since 2011. This stability in leadership, combined with insider ownership, aligns incentives with shareholders.

We’ve seen that in their actions: buying back stock when it’s cheap and not doing empire-building for ego. One slight governance concern could be the related-party nature of the management agreements (Technomar and Conchart are affiliated with the Chairman), but these have been longstanding and at market rates and importantly, GSL’s performance suggests those managers are doing a good job technically and commercially (high uptime, good charter renewals).

In terms of capital allocation priorities, management has outlined a clear framework: maintain fleet assets (i.e., budget for drydock, environmental upgrades), keep leverage moderate (they target net debt/EBITDA under 3x, and currently it’s way below that), pursue accretive growth if available, and return excess cash via dividends/buybacks. They’ve executed on all of these. Even in the Q2 2025 report, they reiterate that they believe retained cash plus operating cash flow will meet all needs and allow for shareholder returns. It’s a calm, confident approach far from the desperate maneuvers one might see in weaker shipping firms.

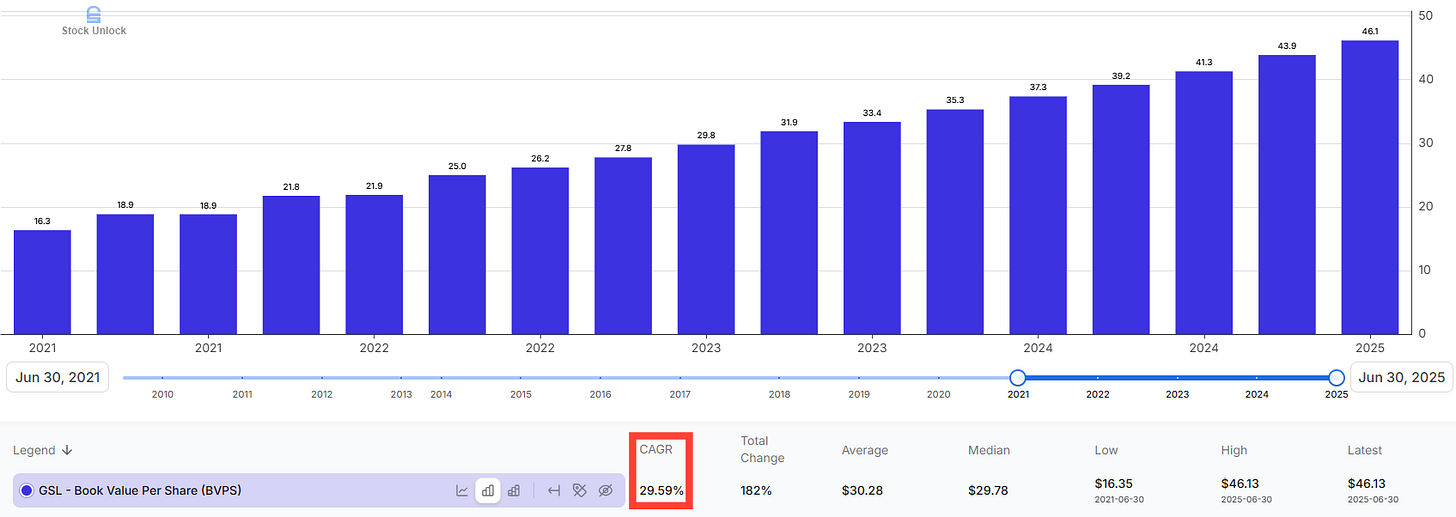

To illustrate management’s savvy, consider this tidbit: GSL has actually increased its book value per share significantly over the past few years. Despite paying out hefty dividends, book value per share grew at 29.6% CAGR from 2021.

Much of that is from retained earnings (because earnings were huge), but also the share buybacks helped. And those vessel book value estimates are likely solid given ships have been selling at gains to book recently. Management’s goal is to close that gap by demonstrating consistent returns and perhaps by continuing buybacks.

All told, I consider GSL’s management team to be disciplined capital allocators with a long-term perspective. They learned lessons from the tough times and took full advantage of the good times to strengthen the company. They also appear to be transparent and financially savvy (for example, how many shipping CEOs talk about cost of capital and ROE as candidly? management acknowledges 30% ROE is unsustainably high and that in steady state it’s more of a cost-of-capital business? That realism is refreshing).

In a sector known for cowboy behaviors, GSL’s team comes off as refreshingly rational and shareholder-aligned. This gives me confidence that if there are storms ahead, they will navigate prudently and if there are opportunities, they will seize them in a value-accretive way.

Financials and Valuation

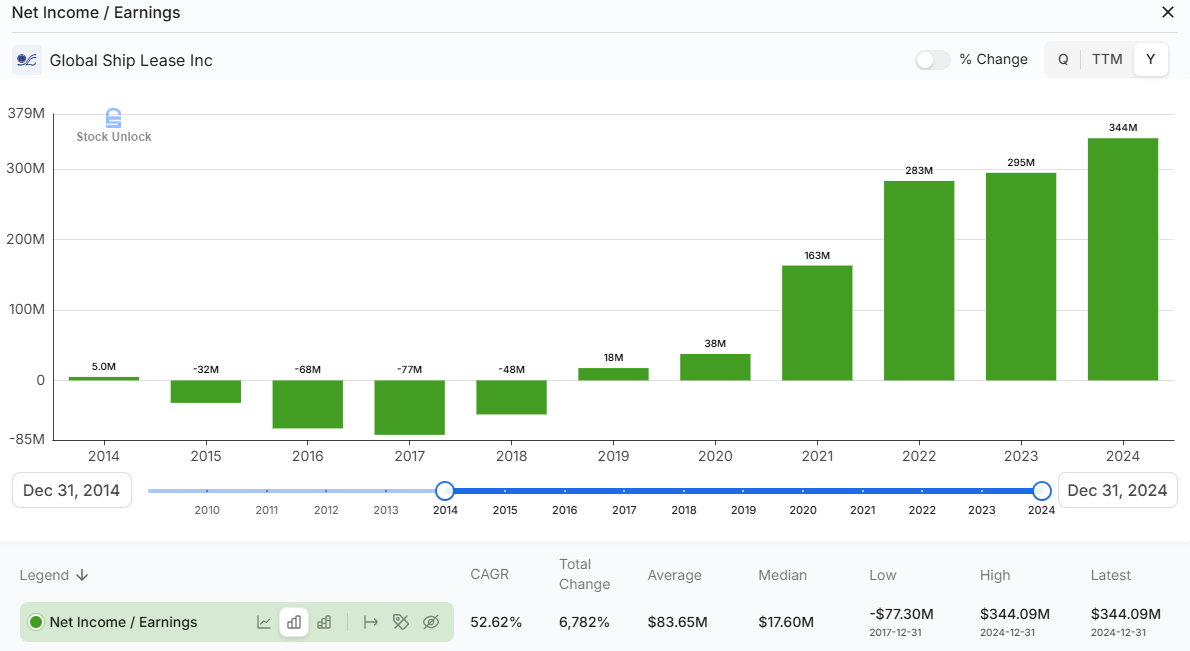

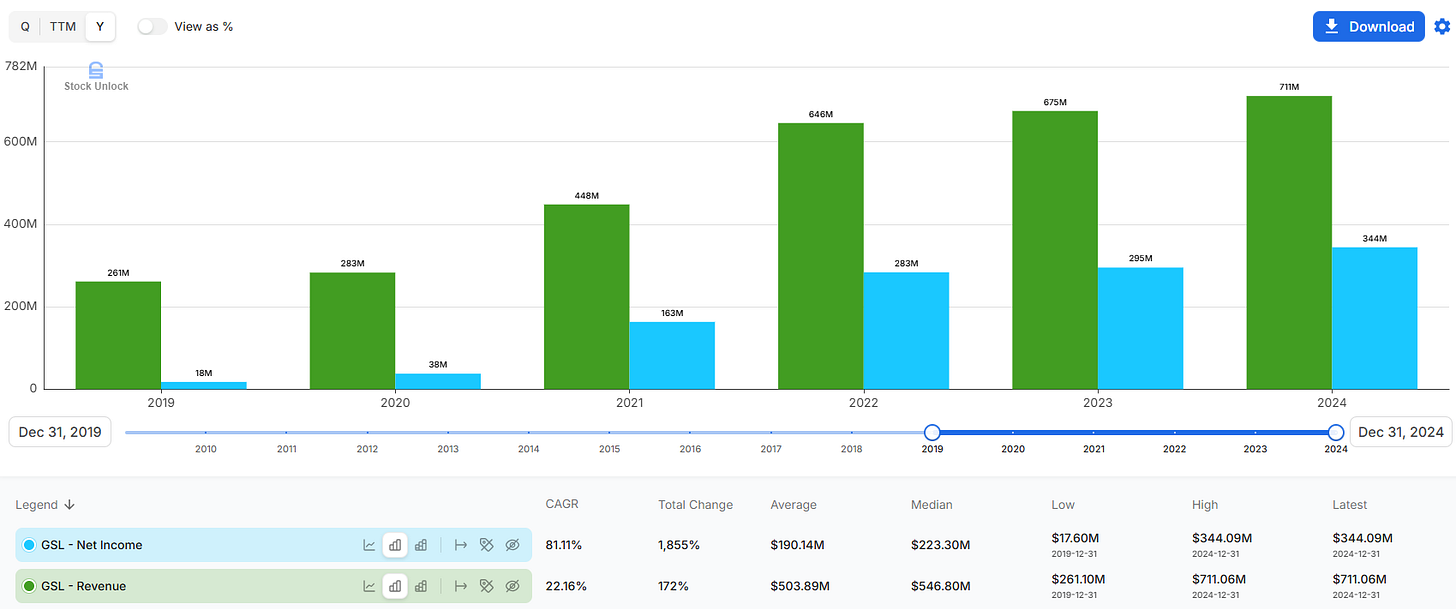

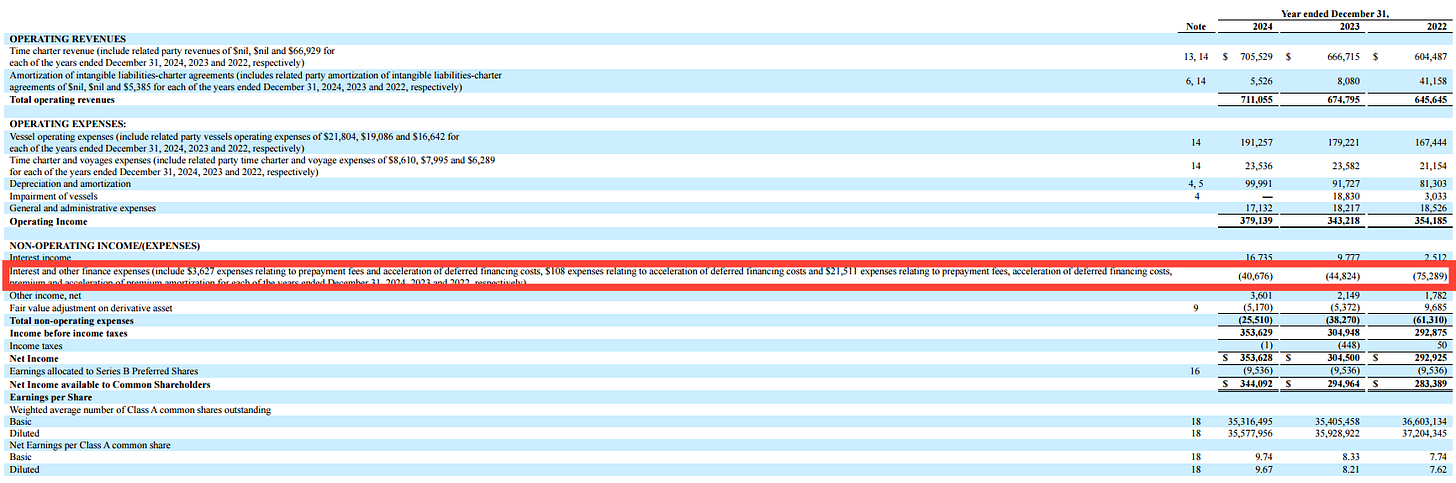

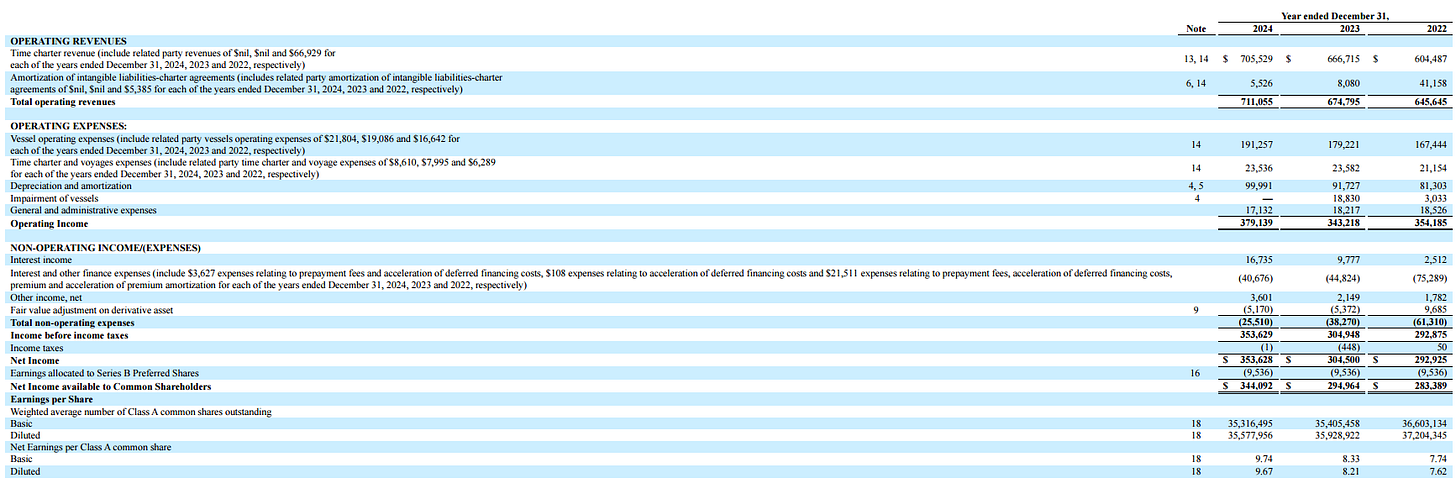

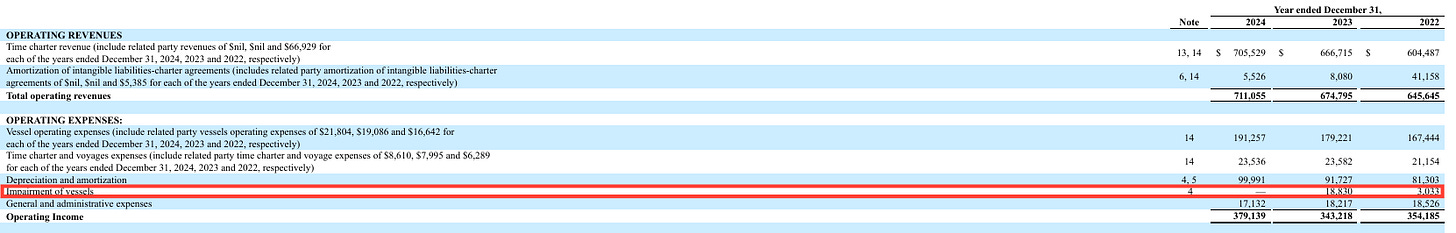

In 2024, GSL had a banner year financially. The company generated $711.1 million in time charter revenue, up 5.4% from 2023, and produced net income of $344 million (after distributing to the prefers). That’s roughly $9.74 in EPS on the 35.3M common shares, an incredible earnings yield of +30%.

GSL’s operating profit margin in 2024 was 53%, and net margin 50%. This reflects the unusually high charter rates in effect. For perspective, 2024’s $711M revenue is more than double the revenue GSL had in 2019 ($261M) before the boom, and net income went from $18M in 2019 to $344M in 2024.

Clearly, these are peak-ish earnings, and the market is assuming they will drop sharply in a few years as charters roll off.

Let’s gauge how much earnings could drop. We know the backlog (as of mid-2025) is $1.612B spread into 2029. If we roughly allocate that: about $702M falls in the second half of 2025 + first half 2026; $542M in H2’26–H1’27; $266M in H2’27–H1’28; $94M in H2’28–H1’29. This suggests that through 2026, GSL will still have a very high revenue run-rate (close to the 2024 level).

By 2027, some of the high-rate charters will have expired, so revenue likely steps down. By 2028–29, revenue would step down further to whatever the “normal” rate environment is.

My valuation essentially takes 2025–2026 as something close to current performance (with maybe a slight dip for minor re-charters or off-hire).

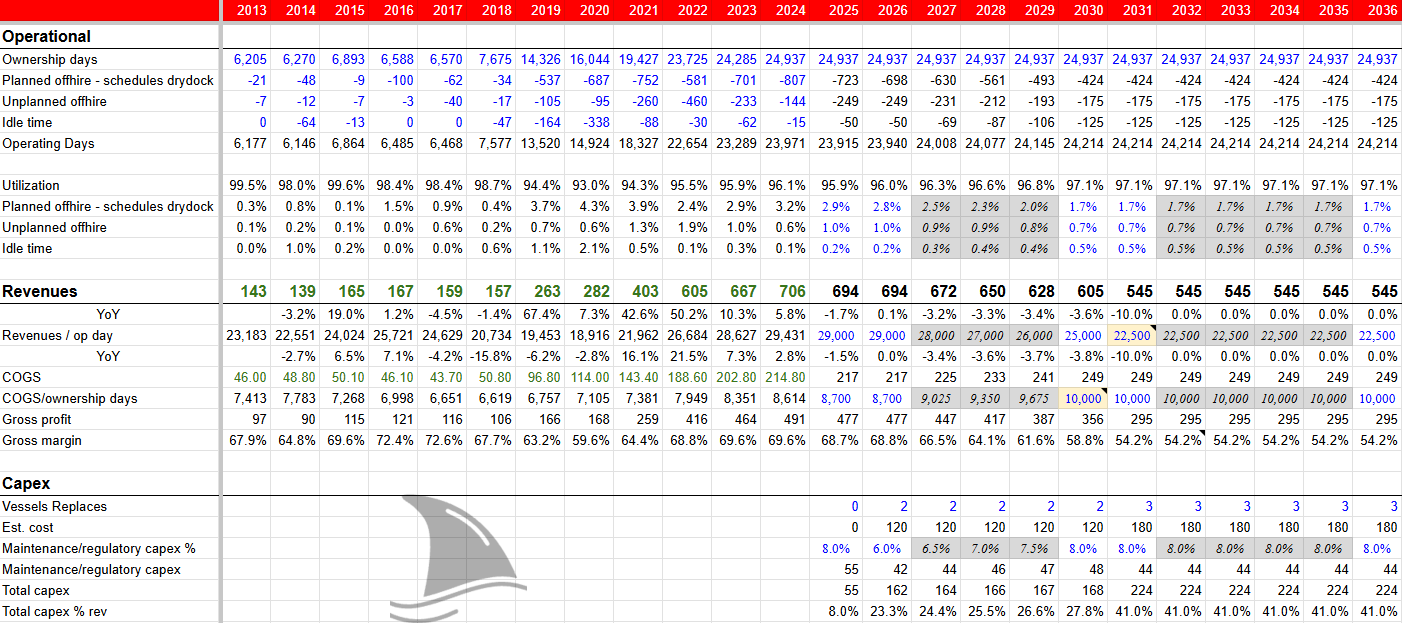

What is “normalized” for GSL? In a downturn, charter rates for mid-size ships might be 30-50% lower than the peak. For example, a vessel earning $30k/day now might re-charter at $15k/day. Operating costs will likely be higher (inflation in crew wages, lube oil, etc., maybe add a couple thousand per day over the next few years).

Let’s suppose by 2027, GSL’s average TCE (time charter equivalent rate) across the fleet is $20k/day, down from perhaps $30k average in 2024. And opex+SG&A+int. per day is maybe $11k (slightly above current due to inflation and interest normalization after hedges expire in 2026). That would yield a roughly $9k/day gross cash margin per ship, versus ~$18k now. So EBITDA margins might compress from ~66% ((30-10)/30) in recent quarters to maybe 45% in the future ((20-11)/20). This is just a rough scenario.

We can also approach via ROE: GSL’s book value at Sep-2025 is $48 per share. If GSL in steady state can earn, say, a 10-12% ROE (which is around its cost of equity in shipping), that implies $5-$6 in EPS long-run. That would be about half the current EPS. That level would still amply cover a $1.50 dividend and allow for growth or buybacks. It’s nowhere near zero.

For valuation, I still start with a DCF, but I now push it through a Monte Carlo simulation rather than rely on a single path.

No fleet TEU growth: I assume GSL does not expand capacity beyond current 70 ships. They might replace or modestly add, but let’s keep fleet size constant. In fact, given upcoming environmental rules, I expect some older ships may be sold for scrap if unprofitable to retrofit; GSL already sold three older ships in early 2025. So flat or slightly down TEU over time.

Charter rates fall in out years: I model charter renewals at much lower rates post-2025. Effectively, revenue declines perhaps 23% from the peak by 2031 and maybe stabilizes there (this builds in the current market weakness even though GSL might secure somewhat above-spot rates due to staggered timing).

Margin compression from inflation: Yes, I assume opex per day continues rising a few percent per year and interest expense rises after hedges expire (though offset by debt reduction). So gross margin slides from 70% in 2024 to maybe 54% by 2031.

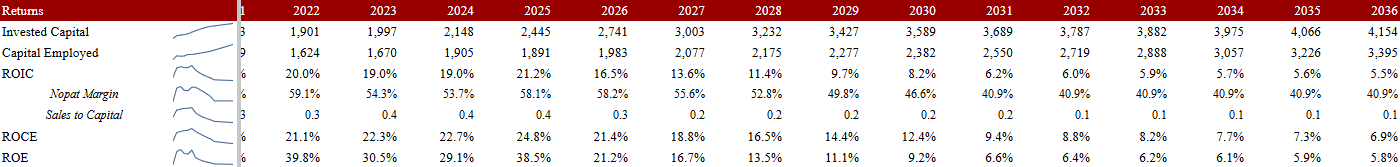

ROIC below the cost of capital: I use 7–9% as a reasonable cost of capital for a containership lessor. When I look at my model, GSL’s ROIC follows a clear downward slope as the high-rate 2021–2022 charters roll off. ROIC starts at 19–21% in 2024–2025, steps down to 16.5% in 2026 and reaches sub-WACC by 2030. In other words, once the super-contracts expire and vessels eventually renew at normalized rates, GSL earns a return that only matches, or slightly misses, its own hurdle rate.

Note that he sales-to-capital ratio keeps declining. The drop is mechanical. As legacy charters roll off, revenue per vessel normalizes to a lower level, yet the capital base keeps growing as GSL spends on vessel replacements and regulatory capex. You end up with more capital tied into the fleet and less revenue per dollar of that capital. The ratio goes from 0.4 in 2024–2026 to 0.3 in 2027, then 0.2 from 2028 onward. This isn’t a sign of operational failure; it is simply what happens when a high-rate period ends while the asset base stays heavy and long-lived. A containership owns 20–25 years of steel. Charter rates do not stay high for 20–25 years.

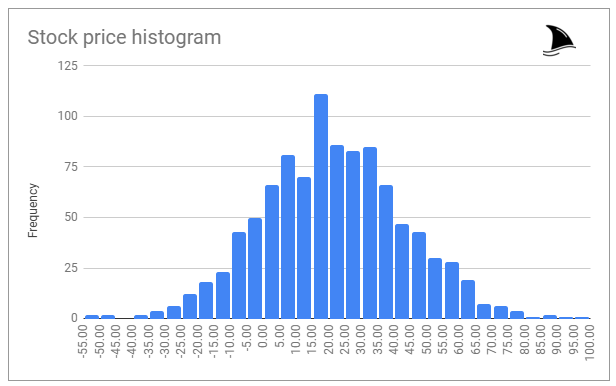

Since no one knows where day rates settle once the cycle resets, I moved away from a single-path DCF and ran a Monte Carlo simulation instead. I used a normal distribution for day rates, daily opex, and the cost of capital.

For day rates I assumed a mean of $20k with a standard deviation of $2.5k; opex (mean $10k and std. dev. of $2k and discount rates 8%-10%).

When I pushed the model through 1,000 runs, the results were surprisingly consistent. The mean gross margin came out around 47%. The mean equity value printed near $25.15 per share, with outcomes spanning from $0 to about $96. Roughly 74% of scenarios landed below today’s share price, which reflects the uncertainty embedded in long-run charter markets. And notably in 16.2% of the scenarios, the equity value is zero.

A $25 central estimate sits under current book value of $48, which makes intuitive sense if long-term returns drift below the cost of capital. The key caveat is obvious: the outputs depend heavily on the simulation inputs, especially the assumed day-rate distribution. If the real clearing rate ends up well below my $20k mean, the valuation slides lower; if it ends up higher, the upside expands quickly.

FCF is high today, but it won’t stay this high once charters reset. On a trailing basis, GSL is throwing off a lot of cash. TTM free cash flow is about $142M, which is 11.5% of the current market cap.

The catch is obvious.

This number reflects the benefit of legacy charters signed during the tight 2021–2022 period, so it overstates the long-run earning power of the fleet. As those charters roll off and rates normalize, free cash flow should trend lower. The market seems to understand this, which is part of why the yield screens so high today.

Margin of safety

I want to emphasize that my valuation deliberately uses conservative inputs. I assume no new fleet growth; I give no value to management potentially reinvesting at cycle lows, which could actually increase value.

I also bake in elevated capex in coming years for drydocks and potential environmental compliance, and I haircut charter rates despite GSL’s backlog being mostly fixed at high levels for several years. Essentially I am baking in the kind of down-cycle that shipping investors have seen many times before rather than a repeat of 2021–2022.

Under those assumptions, the picture is less about upside and more about protecting capital. The distribution is wide, with a heavy tail where equity goes to zero and roughly three quarters of scenarios below today’s price. In other words, there is not much margin of safety at current levels if future day rates clear near my $20k mean.

There is still optionality. If the world avoids the worst-case oversupply, or if GSL uses its balance sheet to buy distressed tonnage at attractive returns, intrinsic value could be higher than my base case. A softer landing where global trade grows 3–4% and newbuild deliveries are delayed or absorbed could support a fair value north of $30; in extreme bull cases I can still get numbers far above that. But I do not want my thesis to rest on those upside paths. With the base-case ROIC drifting toward or below the cost of capital, I see more ways to be wrong than right if I pay today’s price.

Key Risks and Challenges

Risk #1. Supply Surge and “25% Capacity Shock”

The biggest risk is the industry oversupply we discussed. With an orderbook of ~30% of the fleet delivering through 2025, there is a very real possibility that charter rates stay depressed or even fall further once the bulk of new ships hit the water.

If the Red Sea detour ends and ships resume normal routes, that could suddenly release effective capacity equivalent to perhaps 10-15% of the fleet (due to shorter transit times) effectively a capacity shock on top of new deliveries.

In the worst case, the market could be flooded with excess tonnage, driving charter rates to rock-bottom. We could see idle ships piling up in anchorages (though liners would likely scrap older tonnage to prevent that).

For GSL, this risk materializes when its current charters expire and it has to re-charter ships in a buyer’s market. If by 2026–2027 the market daily rate for, say, a 5,000 TEU ship is only $10,000 (which barely covers opex), GSL’s revenue and profit would drop much more than our baseline assumes.

Prolonged severe oversupply could mean GSL’s earnings normalize lower than the $4-$5 EPS I penciled. Maybe it normalizes at $2-$3, in a really bad scenario.

Mitigant: GSL’s high charter cover delays the impact of oversupply. It has through 2025 with little re-charter exposure, and only gradually faces renewals in 2026-27. This gives time for some adjustment (e.g. scrapping of older global fleet) to happen. Also, GSL can choose to scrap its own oldest ships if charter rates fall below opex as it is better to take the scrap cash than operate at a loss.

The current average age ~15 years means by 2027 some ships will be 18-20 years old; if they can’t get decent charters, they’ll be recycled. So GSL won’t run ships at a big loss. It’ll trim capacity, which helps overall supply balance a tiny bit.

Risk #2. Global Trade Slowdown / Geopolitical Risk

Another risk is on the demand side. The valuation assumed a modest growth in container volumes (2-3%). If instead we see a recession or trade war escalation that causes volumes to shrink, that would compound the oversupply problem.

Protectionist policies such as higher tariffs, reshoring manufacturing and geopolitical conflicts disrupting trade lanes could dampen container demand beyond what’s already expected.

For instance, if U.S.-China decoupling accelerates, there could be a structural decline in Transpacific volumes. Or if Europe’s economy stagnates, Asia-Europe trade may not grow. Moreover, unpredictable events like wars (which can reroute or reduce trade) or pandemics (which we saw both hurt and then over-stimulated trade) add uncertainty. GSL is indirectly exposed to global GDP and trade health; historically a 1% drop in global GDP can result in a several percent drop in container volumes (it’s roughly correlated). The risk is that the 2020s see much slower trade growth than the past, either for economic or political reasons, meaning the supply-demand balance stays poor for longer.

Mitigant: GSL cannot control demand, but as long as some baseline level of global trade persists, there will be need for ships. The diversified nature of trade routes means GSL’s midsize ships might find employment in different regions even if certain lanes decline (e.g. if US-China trade falls, maybe intra-Asia or Latin America trade grows, etc.). Also, GSL’s charterers (the liners) are the ones who bear volume risk directly as they might reroute ships, merge services, etc., but they still have to pay GSL’s charter hire unless they lay up ships. Only in extreme cases (charterer insolvency) would GSL lose revenue. So short of a truly massive trade collapse, GSL should keep collecting contracted cash. The risk is more when re-chartering in a weak demand environment, similar to the supply risk above.

Risk #3. Charterer Default or Distress

While I just noted charterers are obligated to pay, what if a charterer cannot? The specter of liner bankruptcy is not zero. We saw Hanjin (Korea’s #7 carrier) go bankrupt in 2016, leaving charter owners high and dry.

In a severe downturn, a smaller liner (or one with high costs) could potentially default. Today, candidates might be regional lines or ones like ZIM which had weaker finances (though ZIM has bolstered its balance sheet with 2021–22 profits).

GSL’s exposure to ZIM is notable. ZIM is a charterer on some contracts (ZIM has actually been re-letting ships it chartered from GSL to others). If ZIM or another customer defaulted, GSL would suddenly have open ships in a bad market and might have to accept much lower rates or idle those vessels.

Also, if a customer tries to renegotiate charters (informally asking lessors for rate relief to avoid bankruptcy), GSL might face a tough decision. Thus far, no major liner is near bankruptcy. Even ZIM, which lost money in 2023,

has $1.8B cash on hand as of June 2025 to weather losses.

The top 5 liners are very solvent (tens of billions in liquidity). So I view this risk as relatively low in the near term.

Mitigant: The liner industry is now consolidated and somewhat protected by state interests (e.g. Korea won’t let HMM fail easily, France backs CMA CGM, etc.). Also, liners learned from Hanjin that bankruptcy is extremely disruptive (cargo gets stranded). So they will avoid it if possible.

Even in a rough 2026, most liners will still have positive cash or at least access to financing. So I suspect GSL’s charters are safe. And even if one did file BK, the ships likely get picked up by other liners (maybe at lower rates, yes, but not zero). GSL might lose some revenue in interim but it wouldn’t be permanent unless a ship is so old no one wants it (then it’s scrap time).

Risk #4. Asset Value Risk

If the market stays depressed for long, ship values will drop. GSL’s book value could erode via impairments. For example, in 2023 they took an $18.8M impairment on two older vessels, likely preparing them for sale.

In a deep downturn, more write-downs could happen if charter-free values fall below carrying. This doesn’t directly affect cash, but it could raise leverage ratios and make the balance sheet look worse. Also, lower asset values mean lower collateral value for loans (though GSL’s debt is already quite low relative to fleet value).

Mitigant: As noted, ship values are still above book in many cases. GSL’s fleet valuation of $1.9B suggests book isn’t inflated. Even if vessel prices drop 20%, GSL would likely still be above water on most ships thanks to depreciation taken and charters enhancing value. And with low debt, GSL wouldn’t be a forced seller at the bottom.

Risk #5. Regulatory/ESG Risks

The shipping industry is under pressure to decarbonize. New IMO rules on carbon intensity (CII) and emissions could penalize older, less efficient ships (like some of GSL’s). GSL will need to invest in engine retrofits, hull paints, etc., or accept speed reductions to comply.

These could increase costs or reduce revenue days. Also, if charterers prefer eco-newbuilds, older ships might lose employment sooner. There’s also talk of carbon taxes or fuel regulations (e.g. EU carbon trading for shipping, IMO 2050 zero emissions target).

GSL might face higher capex or have to eventually replace ships to meet standards. Mitigant: GSL has been proactive in moderate upgrades and typically charterers bear the fuel costs (so they have incentive to run ships efficiently). If a ship can’t meet standards at normal speed, it can slow down (liners might need more ships to maintain service frequency, which ironically could increase demand for ships).

GSL’s purchase of eco ships in 2024 shows it’s gradually renewing fleet quality. Also, any carbon costs would hit the whole industry and charterers would push for lower rates on inefficient ships, but this will be a gradual effect over many years, not an overnight shock.

Verdict: Great Operator, Unattractive Cycle

GSL ticks many boxes I usually like. It has a straightforward business model, long-term charters, high utilization and a management team that used the Covid boom to delever instead of to build an empire. The balance sheet is strong, preferreds are small, and the company has real options if asset values fall. On current numbers, GSL looks optically cheap and spits out a double-digit FCF yield.

The problem is what happens once the party ends.

As high-rate charters roll off and ships are renewed at more normal levels, my model shows ROIC sliding from high teens to the mid-single digits, which is at or below my 7–9% cost-of-capital range for this sector.

In other words, GSL moves from a super-normal capital compounder to a capital-intensive utility. That is not a disaster, but it does not justify paying anywhere near book value unless you have a strong view that future day rates will surprise to the upside.

The Monte Carlo work makes this concrete. Using distributions for day rates, opex and discount rates centred around a $20k per-day mid-cycle rate, the simulated equity value clusters around the low 20s. I bump that to a roughly $25 central value to reflect management quality and the option to buy distressed tonnage. Even then, around 74% of outcomes land below today’s share price and a meaningful minority drive the equity to zero in a harsh down-cycle. That is the opposite of the skew I want when I commit fresh capital to a cyclical industry.

So for now, GSL is a high-quality operator in a mediocre forward return profile. I respect what management has built. But I do not see a clear margin of safety; I see a base case not clearing the cost of capital. I would need either a much lower entry price or fresh evidence that mid-cycle day rates will sit well above $20k to change that view. Until then, GSL stays on my watchlist, not in my portfolio.

Excellent write-up. But are you giving management enough credit for capital allocation - why would they enter into knowingly dilutive charters in 2026/2027...and isn't the variability in rates part of the upside? From my reading the first ships in their cycle don't deliver until 2029 - and buying ships during downcycles could be significantly accretive...can't really argue with your conclusion - guess its a bit of wait and see. Thanks for the analysis.

Your Monte Carlo approach to valuation really captures the risk skew here better than a single path DCF would. The fact that 74% of scenarios land below current price tells the whole story. What strikes me is how managment executed flawlessly on almost every controllabe variable but you're still passing. That discipline is rare and highlights why ciycle timing matters as much as operational excellence in this sector.