What Companies Really Tell You in Their 10-Ks (If You Know Where to Look)

Because every great stock story starts with a 10-K—and ends with whoever actually read it.

(Adapted from my LinkedIn newsletter, Monthly Investing Fundamentals)

Peter Lynch once said,

Behind every stock is a company. Find out what it’s doing.

In other words, if you want to understand a business (and not just its tick, you need to roll up your sleeves and dive into its official reports. For US companies, that means poring over the annual 10-K filing and the proxy statement. Yes, those hefty documents full of legalese and tables might seem long and boring but they’re treasure troves of insight for those willing to dig. Even Warren Buffett attests to the value of voracious reading, he famously said knowledge builds up like compound interest.

In this article, we will walk through how to read and interpret a 10-K and proxy statement without losing your mind.

Table of Contents:

Why Bother Reading These Things?

Why should you spend hours with a dry 10-K or Proxy when you could read a snappy blog summary or watch a YouTube recap?

The short answer: knowledge is power.

The 10-K and proxy aren’t marketing brochures; they’re the raw, unvarnished (ok, slightly varnished) truth that companies are required to disclose. A 10-K is filed annually with the SEC and contains a detailed picture of a company’s business, financial results, and risks.

Unlike the glossy annual report sent to shareholders, the 10-K is all business with no pretty pictures or inspiring slogans. It’s where management has to tell it like it is (to an extent) and where you can catch the things they might have mumbled under their breath on the earnings call.

The proxy statement, on the other hand, is mailed out before the annual shareholder meeting. It’s the fine print of corporate governance: who the directors are, how much the execs are paid and whether there are any potential conflicts of interest or shenanigans afoot.

Reading these documents arms you with information you just can’t get elsewhere. Benjamin Graham insisted on closely examining a company’s financial statements to spot undervalued opportunities. It’s hard to do that if you haven’t read those statements in the first place!

Graham’s classic Security Analysis is essentially an ode to deep-dive research, showing how careful study of reports can reveal a stock’s true value versus the market price. And in Quality of Earnings, Thornton O’glove warns that you can often separate companies that genuinely prosper from those that just project an illusion of prosperity but only if you’re willing to look behind the curtain of the financial statements and footnotes.

Simply put: if you’re investing your hard-earned money in a company, spending a few evenings with its 10-K and proxy is a small price to pay for peace of mind.

There’s another benefit: it sets you apart from the herd. Most casual investors don’t read these filings cover to cover (or at all). By doing so, you join the ranks of more serious investors. And you don’t need a finance degree to extract value, just a bit of patience and a good game plan.

Let’s start with the 10-K.

The 10-K: Your One-Stop Shop for Company Facts

Think of the 10-K as a company’s annual “tell-all” autobiography with the SEC acting as the strict editor ensuring certain topics must be covered. In plain terms, a 10-K is a comprehensive annual report that US public companies have to file each year, containing everything an investor might need to know. It’s structured in a standardized way (thanks to SEC rules) so that once you get the hang of it, you’ll know where to find the information in any company’s 10-K.

Here’s the basic outline:

Part I: The business overview and key risks.

This includes:

Item 1: Business. Essentially a description of what the company does and how it makes money

Item 1A: Risk Factors. Management’s laundry list of all the bad things that could happen.

Item 2: Major properties

Item 3: Legal proceedings the company is involved in.

Part II: The financial nitty-gritty

Item 6: Five-year financial summary

Item 7: Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A), where management discusses the past year’s performance in their own words.

Item 8: Audited financial statements; income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow with notes and the auditor’s report.

Item 9: Discloses disagreements with the auditors.

There are also disclosures about market risks and controls.

Part III: Who runs the company and how they’re paid

This part covers directors and executive officers (Item 10), executive compensation (Item 11), ownership of big shareholders and management (Item 12), and certain relationships or related transactions (Item 13).

Fun fact: Many companies skip fully filling out Part III in the 10-K by simply stating that “this information is in our proxy statement” and then they file the proxy a bit later to cover these items. So don’t be confused if a 10-K seems to be “missing” exec pay or director info; you might have to grab the proxy for those details.

Part IV: Exhibits and schedules

Essentially a list of extra documents and attachments (like contracts, bylaws, subsidiary lists, etc.). Important if you’re doing forensic digging but not mandatory reading for a first pass.

Every 10-K follows this general structure. The consistency is helpful: after you’ve read a few, you’ll know exactly where to look for the MD&A or the Risk Factors in any company. The SEC even tells companies the order of topics to follow. As the SEC’s own guide says,

the “Business” section is a good place to start to understand how the company operates

...and I agree.

Now, don’t get too excited by how orderly it all sounds. In practice, a 10-K can range from a lean ~40 pages to a doorstopper of +300 pages, depending on the size and complexity of the company. The good news is that you don’t have to read every page to get the gist. I often focus on key sections and skim the rest. So what are the parts of the 10-K that deserve your attention?

Let’s break it down.

Key Sections of the 10-K (and How to Decode Them)

Not all parts of a 10-K are created equal. Some sections are pure boilerplate or legal compliance, while others contain the real meat. Here are the most important areas to focus on, and tips for reading them effectively:

Business Section (Item 1)

This is usually a few pages of a plain description of the company’s operations, main products/services, and the markets it serves. It’s the who/what/where/how of the business. Read this to ensure you understand what the company does to make money (you’d be surprised how many investors skip this and then wonder what drives the revenues!).

If you can’t grasp the business model from this section, that’s a red flag. Either the company is involved in something ultra-complicated or the 10-K is poorly written.

As an analogy, the Business section is like the character introduction in a novel. You meet the protagonist (the company), learn the setting and context, and set the stage for the story to come. Graham himself always emphasized understanding a company’s business and industry before getting into numbers, and Phil Fisher (author of Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits) would agree. He suggested investing in what you know. Use this section to see if the company falls within your circle of competence.

Pro tip: If you’re already familiar with the company, you can skim this part for any changes or new initiatives mentioned. Sometimes companies update their strategy or segment info year over year.

Risk Factors (Item 1A)

Here, the company lists all the bad things that keep management up at night (or at least the legal department’s exhaustive list of conceivable risks). It’s often several pages long, and yes, much of it can be generic (“if we can’t compete, our revenues might fall…” No kidding).

However, don’t ignore the Risk Factors. Skim through and highlight anything that seems specific and significant. For instance, if a pharmaceutical company says, “We rely on one supplier for our raw ingredient X,” or a tech company admits, “Our revenue is highly concentrated in two customers,” that’s important to know. This section can tip you off to vulnerabilities.

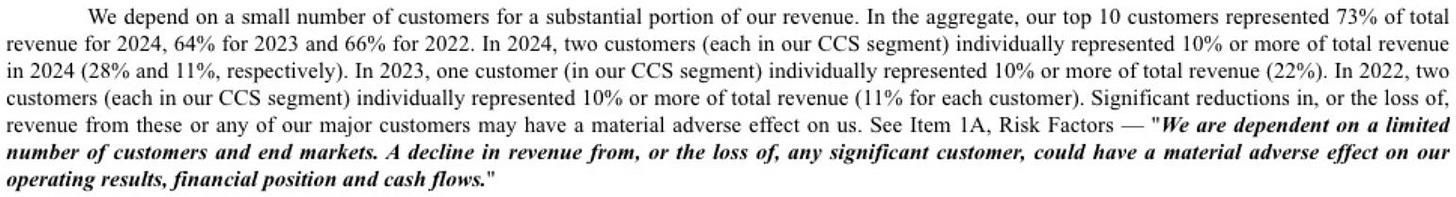

Take Celestica (CLS 0.00%↑), for example. In my deep dive on the company, I flagged its customer concentration risk as 40% of its revenue came from just two customers. That detail came straight from the 10-K. Without reading it, you’d probably miss it.

Read my full deep dive on Celestica here, it’s a solid example of the kind of insight you can uncover when you roll up your sleeves and dig through the filings.

As The Intelligent Investor advises, always invert: think about what could go wrong. A savvy reader might cross-check year-to-year: did the company add a new risk this year (e.g. a new regulatory threat or geopolitical issue)? If yes, why now? It could signal an emerging headwind.

Sure, it’s written in lawyerly tones, but between the lines, you often find the real-world challenges the company faces (commodity prices, labor issues, patent expirations… whatever). Just don’t let the sheer number of risks scare you off and remember, every company has risks; this section helps you understand what they are.

To drive this point home, let me give you an example of what happens when companies don’t disclose material risks properly and how that can blow up in their face:

In 2012, shareholders sued Chesapeake Energy Corporation (EXE 0.00%↑), alleging that it failed to adequately disclose the extent of its CEO’s personal loans and conflicts of interest in its 10-K report. Turns out the CEO had borrowed over $1.1 billion using his stake in company wells as collateral. A juicy detail that somehow didn’t make it into the risk section.

Investors argued that this lack of transparency misled them, especially once the stock dived. The company ended up settling the lawsuit in 2013 for $6.75 million, without admitting wrongdoing. Still, it’s a solid reminder that what’s not disclosed can hurt you and that seemingly “boring” boilerplate sections may be hiding red flags or at least conspicuous omissions.

Management’s Discussion & Analysis (MD&A, Item 7)

This is arguably the most insightful part of the 10-K. In the MD&A, management discusses the operating results and financial condition in plain(ish) language. They’ll explain why revenue went up or down, what drove changes in profitability, how the cash flow looked, and their perspective on the company’s financial health.

This is where you gauge management’s candor and competence. Are they honest about challenges, or do they only tout the positives? Do they blame “macro headwinds” for every shortfall, or do they take accountability for mistakes?

A great management team will provide a clear, coherent story of the year: the good, the bad, and the plans for the future.

Read the MD&A slowly and carefully. It’s okay if some parts are over your head at first (like detailed discussions of accounting changes or complex financial metrics). Focus on the big picture narrative: “We grew sales by 10% mainly due to new product XYZ, but margins shrank due to higher input costs”, that sort of stuff.

If something in the MD&A doesn’t make sense, mark it and come back after looking at the financial statements. Often, the MD&A will also discuss future outlook or known trends. This is management essentially giving you their roadmap and maybe subtle warnings (“we expect competition to increase” or “the first quarter is seasonally weak”).

Compare what they say this year to last year’s MD&A; are they repeating the same promises? Did last year’s plans happen, or are they making excuses? The MD&A and footnotes can reveal whether reported earnings truly reflect economic reality. Watch for any mention of “one-time” items or “adjusted” results. You may need to adjust those out yourself to see the real ongoing performance.

Financial Statements and Footnotes (Item 8)

This is where the numbers live; the balance sheet, income statement, cash flow, and shareholders’ equity statement followed by a pile of footnotes. For many beginners, this section looks intimidating. But don’t skip it as this is where you verify everything management said.

You don’t have to be an accountant to glean useful info here. At minimum, look at the trends:

Are revenues growing?

Are profits (net income) growing, and are profit margins steady?

What about debt levels on the balance sheet, too high relative to assets or equity?

Is cash flow from operations consistently positive and ideally growing along with profits?

A classic piece of wisdom from Graham & Dodd is to analyze a company’s earnings power and financial position over several years, not just one.

For example, calculate a few ratios: current ratio (can they cover short-term liabilities?), debt-to-equity, etc., or look at the footnotes for lease obligations and pension liabilities. If you’re not comfortable with detailed analysis, focus on inconsistencies: Do earnings look strong, but cash from operations is weak? That’s a potential red flag as robust earnings without cash backing them can mean low-quality earnings. It might indicate aggressive revenue recognition (sales recorded that haven’t turned into cash) or high receivables. Similarly, rising inventories while sales are flat could signal that the company is struggling to sell products.

The footnotes will explain accounting policies and often have hidden gems of information: lawsuits, segment performance, revenue recognition changes, off-balance sheet commitments, etc. Train yourself to at least scan the footnotes for anything unusual.

For instance, if a footnote reveals the company changed an accounting method that boosted profits, you’d want to know that. Reading footnotes is a bit of an art (and yes, maybe a slog). Even Thornton O’glove says doing so “is an art, not a science”. But it’s where the “surprises” often lurk. Over time, you’ll get a feel for which footnotes are most critical (revenue recognition, debt and leases, stock options, etc.).

Auditor’s Opinion

Usually found right before the financial statements, it’s a letter from the independent auditor saying whether the financials are presented fairly. Most of the time, it will be an “unqualified” opinion, meaning everything looks okay per GAAP.

If you ever see a “qualified” opinion or a “going concern” warning, that’s a serious red flag. (It means the auditors had issues or doubted the company’s ability to survive.) Also, check Item 9 (in Part II), which discloses any disagreements with accountants. I consider that a red flag if a company has had a spat with auditors or switched auditors under questionable circumstances.

The proxy will often give more detail if an auditor was fired or resigned, including if there were disagreements over accounting. Frequent auditor changes could hint at underlying accounting issues.

Those are the core components worth focusing on initially. In a typical 150-page 10-K, maybe 30-40 pages are truly critical (often the sections above). You don’t necessarily need to read it cover to cover like a novel. The rest (like properties, exact legal proceedings details, and exhibits list) you can skim or reference as needed.

Pro Tips for Navigating a 10-K Efficiently

Tip #1: Use the Table of Contents

Many 10-Ks have clickable tables of contents at the front. Jump to sections of interest (e.g., jump straight to MD&A or Financial Statements).

Tip #2: Leverage Search (Ctrl+F)

If you have the PDF, use the search function for keywords. Looking for a discussion of “competition,” “inflation,” or “cybersecurity”? Just search within the document. This can save time. It’s especially handy to find all mentions of a specific product or segment you care about or to locate where in the footnotes “revenue recognition” is discussed, for example.

Tip #3: Read with Context

Consider reading the latest 10-K alongside the prior year’s 10-K. Compare changes line-by-line, especially in the MD&A and risk factors. If a section was removed or wording changed, that can be telling. (E.g., if last year the company bragged about a certain growth initiative and this year that section is gone, you might wonder what changed.)

Want to compare two 10-Ks line by line to spot changes in under 2 minutes?

In Microsoft Word:

Open Word. Click Review > Compare > Compare... again.

Upload the previous year’s 10-K as “Original” and the latest one as “Revised.”

Click OK, and voila: the changes are highlighted automatically.

In Google Docs:

Open Google Docs and upload both versions of the 10-K.

Click Tools > Compare documents.

Select the other document and hit Compare.

That’s it. You’ll see insertions, deletions, and modifications like if Risk Factor #7 is mysteriously gone or if management quietly walked back last year’s rosy forecast. Super handy when you’re tracking companies you already own or are considering adding to your portfolio.

Tip #4: Skip the Jargon (at first)

Don’t get bogged down if you hit a super-technical paragraph about, say, hedging policies or a tax accounting rule. Make a note and move on; focus on the big picture narrative on the first pass. You can always circle back if it seems important or impacting the numbers.

Tip #5: Check for Consistency

Cross-check what management says in the Shareholder Letter or earnings calls with the 10-K details. If the CEO’s letter (often found in the glossy annual report) says “everything is awesome,” but the 10-K reveals margins are shrinking and debt is ballooning, take note. You want the story and the numbers to align. If they don’t, trust the numbers.

Tip #6: Watch for Red Flags

Certain items in a 10-K are classic red flags. For example: big jumps in accounts receivable relative to sales (could mean they’re aggressively booking sales); inventory piling up (product not selling); large “other” or “non-recurring” gains propping up income (one-time boosts that won’t repeat); frequent use of phrase “material weakness in internal control” (bad sign for accounting quality); or, as mentioned, a change in auditors or complex related-party transactions.

One section of the proxy/Part III discloses related-party transactions, which is basically “did the company do deals with insiders or their relatives’ businesses?”. Too many of those, and you have to question management’s integrity.

Tip #7: Margin of Safety Mindset

Channel Ben Graham’s principle of margin of safety when reading the financials. He liked companies with strong balance sheets such that even if earnings stumble, the company isn’t in peril.

As you read the 10-K, ask: “In a bad year or a downturn, can this company survive? What’s my downside?” The 10-K will often contain the clues (e.g., debt covenants, cash on hand, etc.). This mindset keeps you from getting swept up in rosy projections by focusing on risk as much as reward.

Tip #8: Quality of Earnings Checks

Differentiate between reported earnings and real earnings. Check the cash flow statement. Is cash from operations consistently below net income? If yes, find out why (maybe working capital changes, which could be temporary, or maybe aggressive revenue recognition).

Look at the accounting policies footnote. Did they start capitalizing costs that used to be expensed? Such tweaks can inflate profits without improving the business fundamentally. A Quality of Earnings approach means being a bit skeptical and looking for what’s not being highlighted in big print.

As O’glove put it, approach financial statements with a healthy dose of skepticism and do your own due diligence. The 10-K gives you the raw materials to do exactly that.

Whew, that covers the 10-K basics! Now, onto the other half of our dynamic duo: the proxy statement.

The Proxy Statement: Unmasking the Powers-That-Be

If the 10-K is the story of the business, the proxy statement (Form DEF 14A) is the story of the people running the business and how they’re keeping shareholders in the loop.

A proxy statement is sent to shareholders ahead of the annual meeting, and it’s essentially an invitation to vote on important matters. But it’s much more than just a ballot, it’s a rich source of information on corporate governance.

Here’s what you’ll typically find in a proxy and why it matters:

Elections of Directors

The proxy will list the nominees for the board of directors, along with their bios, ages, tenure, and other directorships. This is your chance to vet the board’s quality. Are they experienced? Do they have relevant industry expertise, or are they just the CEO’s college buddies?

The proxy gives insight into each director’s background. It will also often tell you how many board meetings were held and each director’s attendance. Surprisingly useful (if a director missed half the meetings, that’s a red flag on engagement).

You’ll also see which directors are on key committees like audit or compensation. A strong board has a good mix of relevant experience and independence. If the proxy shows the board is mostly insiders or lacks diversity of skills, you might question how much they challenge management.

Executive Profiles and Compensation (the juicy part)

Ever wonder how much the CEO makes, down to the last perk? The proxy is where executive compensation is laid bare. There will be tables showing salaries, bonuses, stock awards, options, retirement plan contributions, you name it, for the CEO and top 3-5 other executives (Named Executive Officers, or NEOs).

Why should you care? Because compensation drives behavior. The proxy’s compensation discussion (often called the CD&A: Compensation Discussion & Analysis) explains the philosophy: are they rewarding short-term stock price pops or long-term value creation? Are goals based on real performance metrics or easily achievable targets?

The proxy statement shows if a company puts its shareholders first or just looks out for its own insiders. If you see a CEO making tens of millions while the stock languishes or getting big bonuses in a year the company lost money, that’s a bad sign. Look for alignment: ideally, a significant chunk of pay is performance-based or in stock/options that only pay off if shareholders also benefit. The proxy will even show a comparison of CEO pay to median employee pay (a recent SEC requirement), which can be eye-opening but varies by industry.

Insider ownership is another key piece: the proxy will list how many shares each exec and director owns. If the CEO owns zero stock but gets a huge cash salary, their incentives might not align with yours as a shareholder. Conversely, if management has, say, 5% of the company in stock, they have skin in the game. I like to see insiders owning meaningful stakes as it often makes them act like owners.

The proxy also discloses option grants: are they getting lavish options every year, and are those rewards contingent on performance? Ideally, options should be structured so that they only become valuable if the stock price rises above a certain bar, encouraging management to drive long-term growth.

Shareholder Proposals and Voting Matters

The proxy will outline the items up for vote. Standard ones include electing directors, ratifying the auditor (usually a formality), and say-on-pay (a non-binding vote on executive compensation).

Sometimes there are shareholder proposals, which could be anything from “publish a sustainability report” to “require an independent board chair.” These are great to read because they highlight current debates or discontent.

For example, if a shareholder proposal asks the company to separate the CEO and Chairman roles, it may indicate that some shareholders think management has too much unchecked power. Or a proposal to increase environmental disclosure might signal that stakeholders want more transparency on ESG issues.

The company will include a statement recommending how to vote on each. Unsurprisingly, they often recommend voting against shareholder proposals that management doesn’t favor. Even if you’re not voting, this section shows you hot-button issues. It’s like reading the minutes of a town hall and you see what topics are being raised.

Related Party Transactions

This is the section where they must disclose any deals between the company and its insiders. For instance, if the company leased office space from a firm owned by a board member, that has to be described. Or if the CEO’s brother-in-law is a supplier.

These relationships aren’t necessarily deal-breakers, but they require scrutiny. The proxy will often detail the nature of the relationship and the dollar amounts. If you see, say, the company is buying $5 million a year of product from a business owned by a director, you might wonder: is that the best deal for the company or is the director self-dealing? The fewer conflicts of interest, the better. Many companies have a policy that any such transactions must be at “arm’s length” and approved by independent directors, the proxy might mention that. But if you see too many cozily interlinked deals, be wary.

Corporate Governance Details

The proxy usually has a section on how the company is governed. This can include the board’s structure (separation of CEO and Chair roles, or not), how often directors are elected (annually or staggered terms), and what percentage of shares insiders own vs. institutions.

There may also be info on board evaluations, continuing education, etc. Some of this can be boilerplate, but it can reveal things like whether the company has anti-takeover defenses (poison pills, classified board, etc.), which, as a shareholder, you might not love.

Also, look for the audit committee report. It usually just says, “We reviewed the financials with management and found everything okay” in standard language. But if there were any issues, they’d surface here or in the auditor’s report.

Changes in Auditors

Occasionally, a proxy might detail if the company changed its independent auditor and why. As noted, if an auditor resigns or is fired, the company must disclose if there were any disagreements over accounting matters.

If you ever stumble on that disclosure, it’s a huge red flag. It suggests serious issues were brewing (auditors usually don’t part ways with a client unless there’s smoke, if not fire).

Overall Business Health (in brief)

Interestingly, some proxies include a summary of the company’s performance or strategy outlook, almost like a mini-annual report. For example, management might highlight key initiatives or challenges ahead in the proxy’s introduction. This isn’t as detailed as the 10-K’s MD&A, but it can reinforce what’s going on.

Valuable insights can sometimes be gleaned here about backlog, margin trends, or opportunities and concerns that maybe didn’t get full airtime on earnings calls. If nothing else, it’s a consistency check against the 10-K narrative.

To sum up the proxy: it’s your window into the quality of the stewardship of the company. It helps you answer questions like:

Are the executives and board members competent and shareholder-focused?

How are they being rewarded?

Do they eat their cooking (own stock)?

Are there any conflicts of interest or governance concerns?

A strong proxy statement (from an investor’s standpoint) shows a transparent management team that is paid reasonably relative to performance, overseen by an independent and skilled board, with policies in place that align their interests with shareholders’.

A poor or sketchy proxy might reveal an overpaid CEO, a rubber-stamp board full of cronies, generous “sweetheart” loans or perks for execs (like the company paying for the CEO’s personal use of the corporate jet and forgiving loans), and proposals that serve insiders more than owners.

As an anecdote, over the years, I have avoided disasters by reading proxy statements, e.g., spotting that a supposedly high-flying company’s execs were bailing out (selling shares while touting the stock), or noticing that management’s pay was entirely detached from any real-world performance metrics (a sign of a potential agency problem where management might enrich themselves even if shareholders suffer).

On the flip side, finding a proxy where management’s incentives are well-aligned (say, lots of out-of-the-money options that only reward them if the stock rises substantially) can give you confidence that the leadership will strive to build long-term value.

How to Read 10-Ks and Proxy Statements Efficiently

By now, you might be thinking, “Alright, that’s a lot of info. How do I actually tackle these documents without spending a lifetime?”

Here’s a simple approach to reading a 10-K and proxy, especially for beginners:

Skim the 10-K’s Business and MD&A first to get the story of the company and its recent performance. This gives you context and frames the numbers you’ll see later.

Flip to the financial statements, glance over the key figures (revenues, net income, EPS, assets, debt, cash flow) and see if anything jumps out (big changes, new line items, etc.). Read the footnotes for any big changes in accounting or unusual items. Don’t worry about comprehending every dollar, focus on trends and anomalies.

Return to any complex parts of the MD&A or Risk Factors that you marked, now that you’ve seen the numbers. They might make more sense now. For example, if the MD&A said profit dropped due to “lower capacity utilization,” and now you see that inventory spiked, you can connect those dots.

Read the proxy (or relevant Part III info) with an eye on the people aspect: Check exec compensation tables (do the rewards make sense relative to results?), scan the biographies of key leaders (seasoned or newbies? any concerning past?), and note insider ownership levels. See if the board has the chops to guide the company. Also note if any shareholder proposals or governance issues are being highlighted.

Make a short list of the positives and negatives you gleaned. For instance: Positive: Company grew revenue 15% organically, CEO owns $10 million in stock, business has low debt. Negative: Customer concentration is high (top 2 clients = 30% of sales), CFO resigned and new one is on board, lots of stock options could dilute shareholders if all exercised. This exercise forces you to articulate what you learned.

Cross-check with external sources as needed: If something in the 10-K references an industry trend you’re not aware of (“due to new regulation X, we expect increased compliance costs”), you might look up that trend separately. Or, if the proxy mentions a lawsuit, you could search the news for that. The 10-K and proxy will tell you what the company is facing; you can always seek outside info to grasp the implications.

Remember, the goal of reading these is not to memorize every number or phrase but to form a coherent understanding of the business’s health and leadership quality. Over time, you’ll develop pattern recognition; you’ll know what seems “normal” for a company or industry and what doesn’t. That’s when reading filings gets interesting: you start catching subtleties, like a slight change in wording from “we have adequate liquidity” to “we believe we have adequate liquidity” (extra hedge word noted!), or noticing the CFO’s pay jumped 50% because of a “one-time retention bonus” (hmm, were they considering leaving?).

Also, don’t be discouraged if the first few 10-Ks you read feel overwhelming. It’s like learning a language. Initially, you might have to look up terms (what the heck is a deferred tax asset? what does “goodwill impairment” mean?). But each report you read builds your financial vocabulary and confidence. Benjamin Graham’s The Interpretation of Financial Statements is a handy classic that walks through the basics of balance sheets and income statements if you need a primer. And there are modern guides and websites for every skill level.

Finally, a note on tone and trust: Regulatory filings like the 10-K and proxy are where companies have to comply with rules, but there’s still room for personality. Some management teams write candid, even enjoyable MD&As that honestly discuss challenges (a refreshing find!), while others write dense, jargon-laden paragraphs that obscure more than they reveal.

For example, the Jaffee family (owners and long-time managers of ODC 0.00%↑) are a textbook case of transparency. Their shareholder letters and filings read like an honest conversation rather than a legal disclaimer. They openly discuss both wins and stumbles, giving us real insight into how the business is run and what drives its results.

Pay attention to this tone as it often correlates with corporate culture. For example, Warren Buffett famously writes his shareholder letters in plain English with a dose of humor and folksy analogies (and Berkshire’s 10-K, while comprehensive, is relatively straightforward). If a company’s filings are needlessly convoluted, it might reflect either an overly bureaucratic culture or, worse, an attempt to mask issues. Charlie Munger said he looked for businesses run by people who are “able to articulate their thoughts clearly” because if they can’t explain what’s going on in understandable terms, maybe they don’t fully understand it, or they’re hiding something. Food for thought as you read.

By now, you should have a clearer idea of how to approach these documents and why they’re worth your time. You don’t have to become an accounting savant or a corporate lawyer; even a beginner-friendly, common-sense reading of 10-Ks and proxies will dramatically improve your investment due diligence. You’ll start seeing through the hype and headlines and gain insight into the actual condition of a company.

Conclusion: Embrace the 10-K (You Might Even Start to Like It)

Reading 10-Ks and proxy statements might never become as fun as binge-watching the latest Netflix series, but they don’t need to be a form of torture, either. Approach them with curiosity: You’re a detective hunting for clues about what makes a company tick (and what risks could make it stumble). Over time, you’ll likely find a rhythm and maybe even catch yourself enjoying the empowerment that comes from gleaning information first-hand.

There’s a certain satisfaction in not having to rely on second-hand summaries because you’ve seen the source with your own eyes. As you develop this skill, you’ll be practicing what Graham, Dodd, Lynch, Buffett, and many other investment greats preached: doing your homework and thinking for yourself.

In a slightly sarcastic nutshell: reading 10-Ks is like eating your investing vegetables. Not always delectable, but very good for you. And the proxy is like the fiber that keeps the market healthy by exposing governance that might otherwise cause indigestion. 😏

So, next time you’re considering an investment, try downloading the company’s latest 10-K and proxy. Skim the sections we talked about, jot down a few observations, and see how it informs (or even changes) your investment thesis. You’ll be surprised how often something in the fine print can materially impact your view of a company’s value or risks.

Plus, imagine the swagger of being able to say, “According to the 10-K, the company’s operating cash flow grew faster than net income indicating high earnings quality” at your next meet-up, instead of just parroting Jim Cramer.

Jokes aside, becoming fluent in 10-Ks and proxies is a superpower for the serious investor. It’s a bit like X-ray vision into a company’s inner workings and power structure. Many won’t take the time to do it, but those who do will often find themselves a step ahead.

One last tip

Keep a notebook or document for each company you research, and record key points from the 10-K and proxy. Read my tips on building your knowledge base here.

Over the years, this becomes an invaluable reference. You can track how a company evolves, how management’s tone changes, how financials trend essentially building your cumulative knowledge base. This is exactly how long-term fundamental investors build deep expertise.

What’s the most surprising or illuminating thing you’ve ever learned from a 10-K or proxy statement that you wouldn’t have known otherwise?

Regarding the topic of the article, it's funny how something so crucial is often buried under layers of corporate prose. You make a great point about those documents being treasure troves. With all the data parsing involved, what do you think is the biggest "red flag" or subtle hint that AI might miss, that only a human reader can truely spot? Very insightful, thnks for demystifying this.