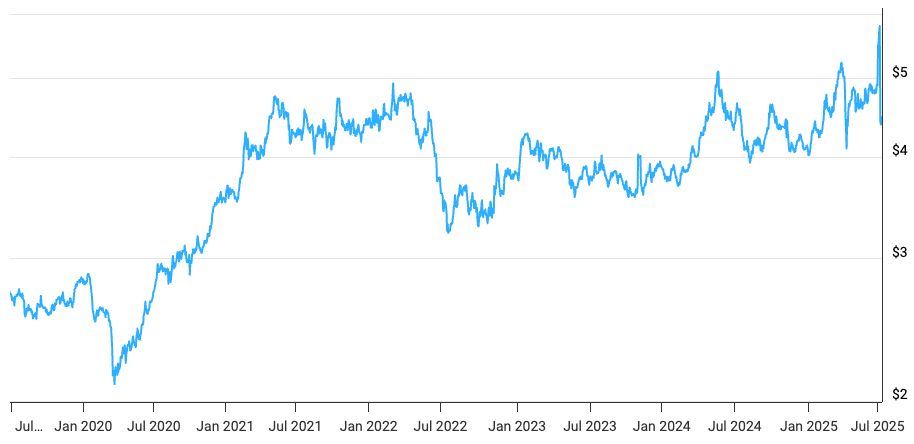

Mueller Industries (MLI): Why 28% Margins Won’t Last Forever

Mueller Industries rode copper prices to record profits. Here’s an in-depth stock analysis on why this great business isn’t a buy at today’s price.

Important note: This is an analysis of a company I ultimately did not add to the portfolio. My paid subscribers get access to the deep dives on the high-conviction, high-reward picks that do make it in.

Normally, I only publish deep dives on companies that are either in the portfolio or exiting it (as post-mortems). This one is different. I’m sharing it for two reasons. First, Mueller Industries (MLI) could make it into the portfolio if the price falls enough to offer a better risk/reward. Second, it’s a good case study in a mistake I see investors make often: assuming that current performance and margins will persist indefinitely, then projecting those numbers straight into the future. By digging into the fundamentals of both the company and its industry, you can separate structural improvements from short- or medium-term boosts.

In MLI’s case, I think the margin surge of the past couple of years has been helped along by rising copper prices. Because copper is cyclical, there’s a strong case that those margins will come down.

Enjoy the deep dive!

I remember watching copper prices skyrocket in 2021. A friend joked that someone out there was literally turning copper into gold.

It turns out, Mueller Industries was doing just that. This century-old manufacturer quietly rode a once-in-a-generation surge in copper to record profits.

It felt like finding a hidden gem, an unsexy pipes and fittings business minting money while nobody paid attention. I had to ask myself: Was this my next great stock pick, or just a shiny copper penny?

The Thesis in a Nutshell

Mueller Industries (MLI 0.00%↑) is a well-run industrial company that makes essential copper and brass products for plumbing, HVAC, and infrastructure. It benefited massively from the pandemic-era construction boom and inflation. Its profit margins nearly doubled thanks to surging copper prices and favourable inventory accounting.

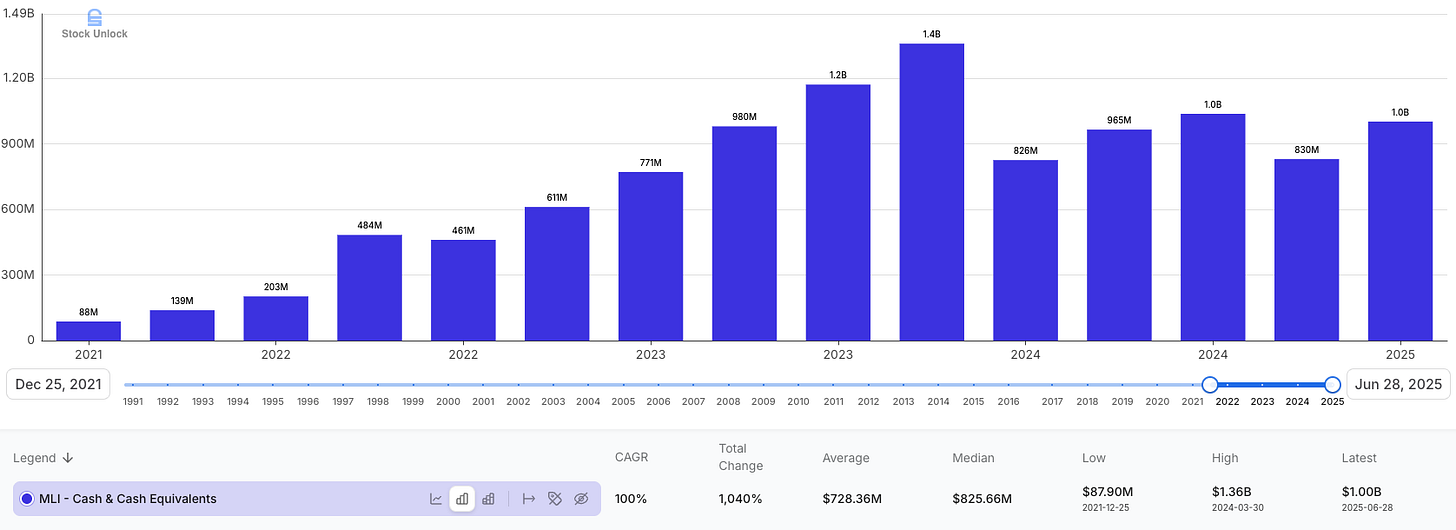

The company has no debt, over $1 billion in cash, and a shareholder-friendly management (big buybacks and dividend hikes). However, I expect its fat margins to slim down as things normalize, and my valuation ($109 per share) is only ~16% above the market price.

In short, it’s a good, “boring” business, but not quite cheap enough for me to buy, given the risk that today’s high profits won’t last.

Now let’s dive in and see how Mueller turned copper into cash and why I’m ultimately passing on this one.

Table of Contents:

Company History and Evolution

MLI has been around forever (since World War I), making the unsung hardware that keeps civilization running. Headquartered near Memphis, it built a reputation for quality in copper tubes, brass fittings, valves, and other plumbing/HVAC components.

Over the decades, Mueller steadily expanded, and it’s now the only fully vertically integrated maker of copper tube, brass rod, and related bits in North America. Mueller controls everything from raw copper to finished pipes. This old-line manufacturer chugged along for years with modest profits and single-digit margins, supplying builders and factories with “boring but vital” parts.

In the 2010s, Mueller was solid yet unremarkable.

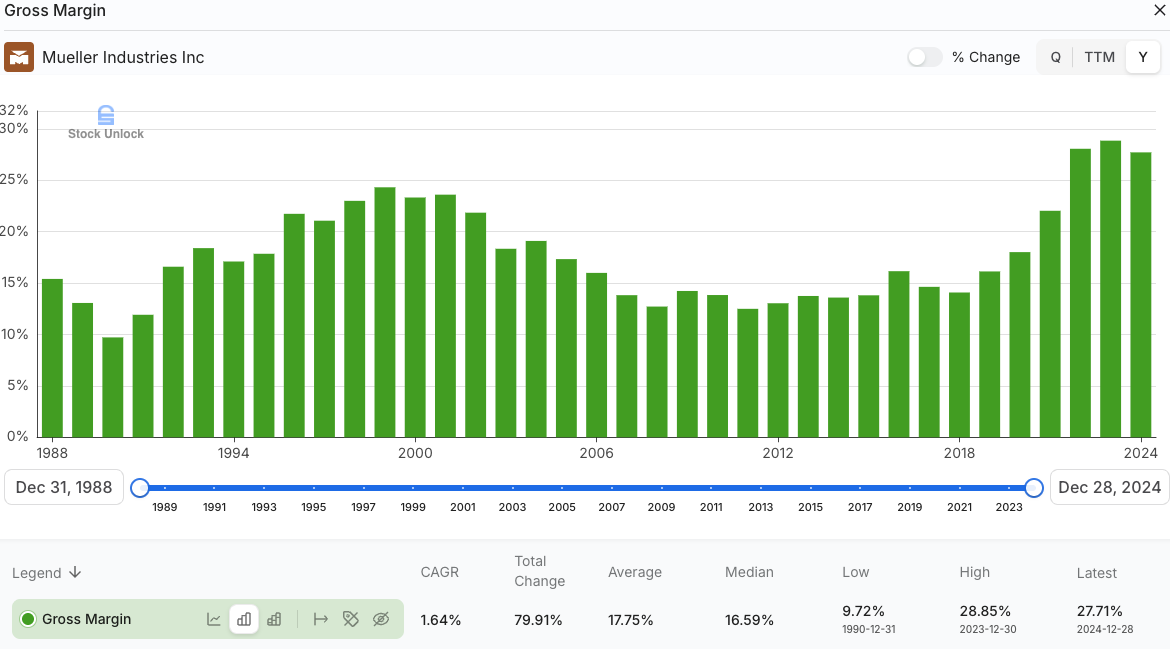

New housing starts and construction spending drove its sales, as you’d expect for a plumbing/HVAC supplier. But competition was stiff and copper is a commodity, so historically Mueller’s margins were thin (mid-single digits).

The company’s evolution accelerated in recent years. Under long-time CEO Greg Christopher, Mueller has made strategic moves: selling off non-core businesses and buying companies to expand into higher-margin niches.

For example, in 2021, Mueller acquired ATCO Flex (a duct systems maker) to bolster its Climate segment, and in 2024, it paid $575M for Nehring, a manufacturer of electrical wire and cable. Nehring plugs Mueller into the utility and telecom markets, giving it a toehold in the growing electrification trend (think power grid upgrades and data centers). These moves shifted Mueller’s portfolio more toward value-added products and diversified it beyond pure plumbing.

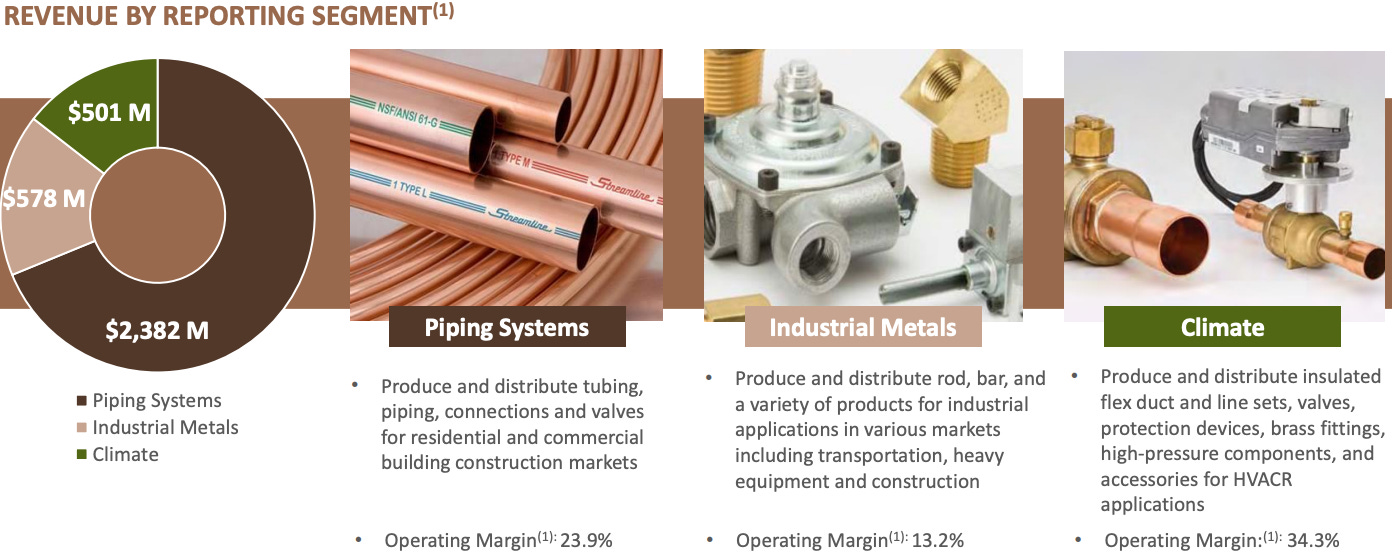

Today, Mueller has three segments.

The Piping Systems segment is its legacy core: copper tubes, fittings, line sets (pre-insulated tubing for A/C), and various valves and nipples. This is the workhorse, supplying wholesalers and OEMs for plumbing, heating and refrigeration uses.

Industrial Metals is the next chunk, making brass rods, aluminum and copper forgings, and other metal components for industrial and automotive customers.

Finally, the Climate segment produces items for HVAC and refrigeration, like valves, heat exchangers, and insulated ducting.

Piping is by far the largest (roughly two-thirds of sales) and traditionally the profit engine. Climate and Industrial are smaller but can have niche, high-margin products. Mueller’s breadth sounds a bit dull (tubes, rods, ducts), but it’s all basic infrastructure stuff that keeps modern life comfortable.

How Mueller Makes Money (and Why Copper Price Mattered)

Mueller makes money the old-fashioned way: it buys raw metal, adds value through manufacturing, and sells the finished product at a markup.

For example, it might buy copper cathode at $4.00 per pound, extrude it into a pipe, and sell that pipe at $4.50 per pound equivalent. That $0.50 gross profit per pound (just an illustration) is essentially the “spread” Mueller earns for processing the metal. The volume of pounds and the size of that spread determine its earnings.

This model works best when Mueller can pass along raw material cost increases to customers, and historically, it does try to do that. In stable times, the spread is fairly steady. But in volatile times, inventory accounting can make a big difference to reported profits.

Mueller uses FIFO (First-In, First-Out) accounting for inventory. This means when they sell a product, the cost on the books comes from the oldest inventory layers first. During a period of rising commodity prices, FIFO causes profits to appear higher.

Why?

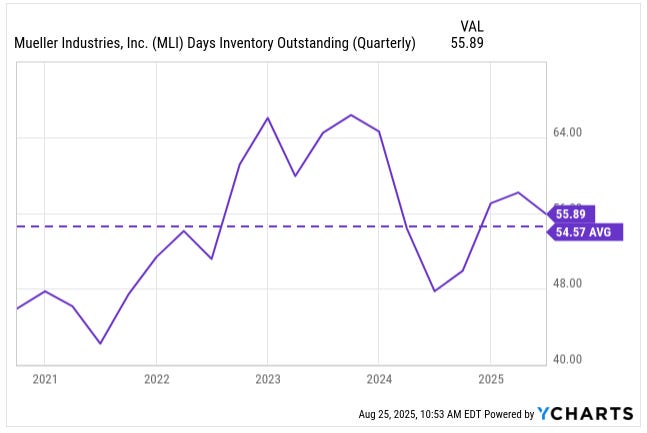

Mueller churns inventory in about two months on average (~56 days outstanding).

So whatever they sell today is priced at today’s copper market, but the cost they book reflects copper purchased roughly two months ago. When copper is climbing, that lag means reported margins look fatter. When copper is falling, it works against them; they’re selling at today’s lower prices but expensing copper bought at higher levels.

This is exactly what happened recently. As copper prices surged, Mueller’s cost of goods lagged the market price, so it booked fatter gross margins. On the flip side, in a sharp copper downturn, FIFO could crimp margins or even cause losses.

In short, Mueller’s profitability is tied not just to how much it sells, but also to the trajectory of copper costs and the timing lag created by its inventory cycle.

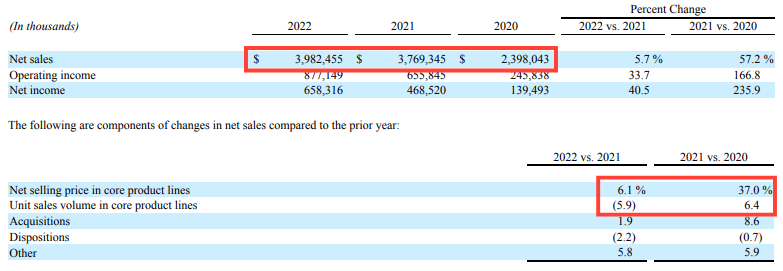

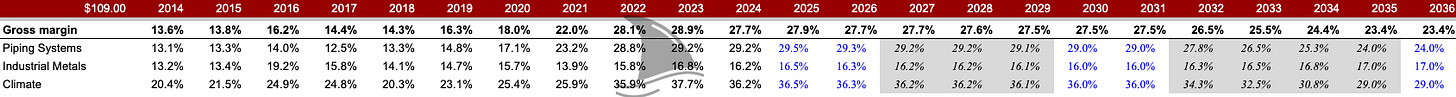

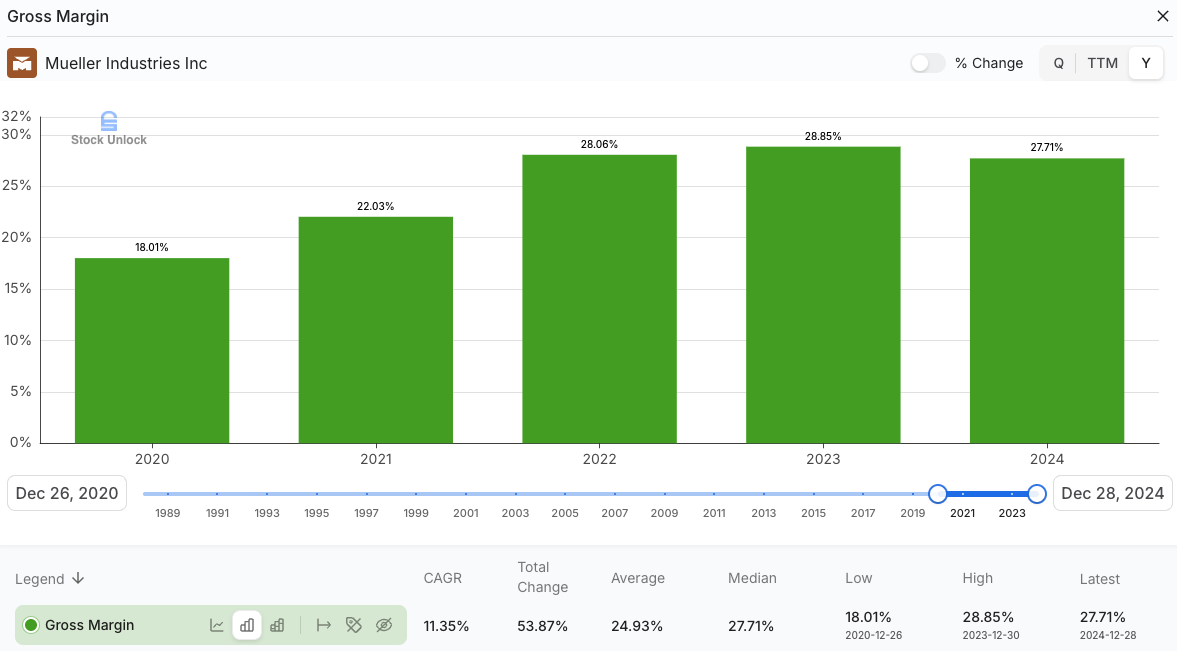

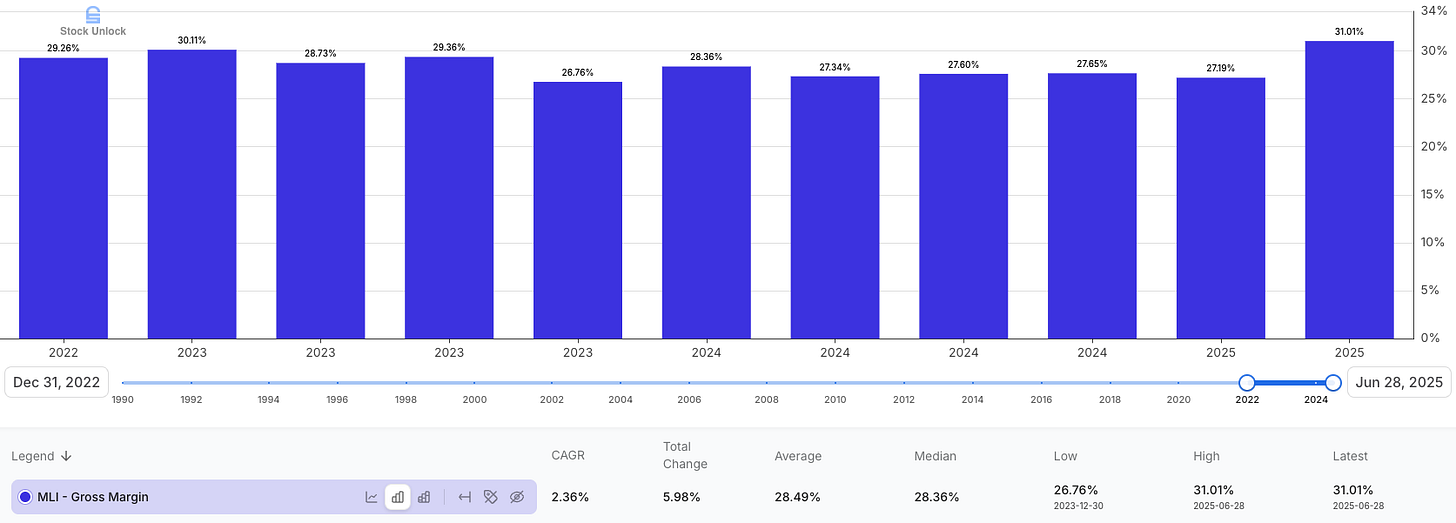

We saw this dynamic play out in dramatic fashion. Before 2020, Mueller’s gross margin hovered around the high teens (%).

Then came the pandemic construction boom and supply shocks, copper spiked to all-time highs, and Mueller was able to charge accordingly. Its gross margin shot up to the high 20%s.

The company frankly “defied gravity” on margins, printing over 20% operating margins versus mid-single digits historically. To be clear, part of this was real operational improvement (better mix, efficiencies), but part was temporary inventory gains from FIFO and inflation. Management even acknowledges this in filings. When input costs swing wildly, FIFO accounting boosts or dents the reported earnings. The last few years have been a perfect setup for Mueller to harvest outsized profits from its inventory.

Mueller’s unit economics are otherwise solid. It runs efficient plants (many in low-cost regions or right-to-work states) and benefits from scale as one of the largest players in its niche. Being vertically integrated, it can capture margin at multiple stages (casting, extruding, finishing). It doesn’t have to outsource a lot. This has kept its manufacturing cost per pound low, which is a competitive advantage, especially when demand is steady.

The company claims it can pass through most raw material cost changes to customers. It strives not to be squeezed by copper price moves long-term. During normal times, that means Mueller’s dollar gross profit per unit is relatively stable, and it is the volume of units (pipes, rods, etc.) that drives growth. But in abnormal times like 2021-2022, that dollar spread ballooned.

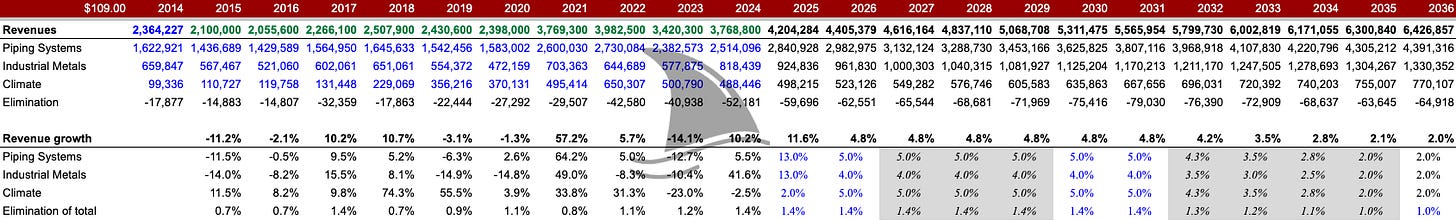

A quick example: In 2021, Mueller got a double boost: copper prices jumped +37%, and unit volumes in core product lines grew +6.4%. That helped drive sales from $2.4 billion in 2020 to $3.8 billion in 2021. By 2022, volumes slipped 5.9%, yet revenue still edged higher to just under $4.0 billion, thanks mainly to stronger pricing (+6.1%). Net income over this stretch more than quadrupled, rising from $139 million in 2020 to $658 million in 2022.

It wasn’t about new products or dramatic efficiency gains. Mueller simply benefited from selling the same copper tubing at much higher prices. Picture a grocery store buying milk at $2 and charging $4 during a shortage. It’s great while it lasts, but no one should expect milk to stay at $4 forever. That’s the lens I used when looking at Mueller’s future.

Industry Landscape and Copper Outlook

Mueller operates in a cyclical, old-school industry: building and industrial materials. Roughly 90% of its sales are tied to construction and renovation activity (plumbing and HVAC in homes, commercial buildings, and appliances). This is reflected in the cyclicality of its gross margin.

When housing starts and commercial builds are robust, Mueller’s order books stay full. When construction slumps (high interest rates, recessions), demand for pipes and fittings slows. We saw this recently, as mortgage rates jumped and new home construction cooled in 2023, Mueller’s Climate segment (which sells a lot into residential HVAC) saw sales drop over 20%. It’s a classic cyclical pattern.

The copper outlook is a double-edged sword for Mueller. On one hand, many experts foresee a strong long-term demand for copper. The push for electrification (EV, renewable energy, grid upgrades) could fuel a secular bull market in copper over the coming decade. That would mean a tailwind for Mueller’s volumes (e.g. more copper wiring, more HVAC and plumbing for EV infrastructure, etc.), and potentially higher pricing power if copper remains in short supply.

Mueller’s new electrical cable business (Nehring) positions it to benefit if U.S. infrastructure spending on the grid ramps up. So structurally, the demand picture for copper-based products isn’t bad at all.

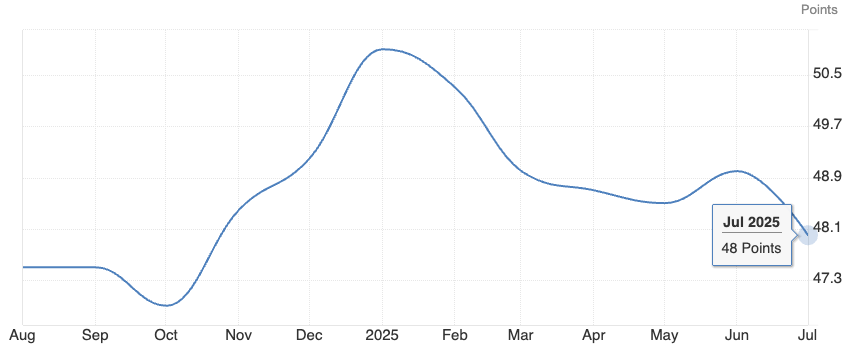

On the other hand, copper is a commodity subject to booms and busts. After hitting record highs, the price of copper has been choppy. It eased off peaks and could fall further if the global economy slows. Short-term, the manufacturing PMI is below 50 (signalling contraction), and sectors like appliance and automotive are not exactly booming.

Mueller itself warned that business conditions have been unsettled and residential construction remains subdued (with higher interest rates being the culprit). If a broader recession hits, copper demand (and price) might dip, which could squeeze Mueller’s margins as discussed. The company, fortunately, has no commodity hedges to blow up (it buys as needed), but it’s not immune to industry down-cycles.

Competition in Mueller’s world comes from two areas: other metal part makers and substitute materials. In copper tubes and fittings, Mueller’s main U.S. competitors are private or foreign-owned players like Cerro Flow and Cambridge-Lee (Mexican-owned). There are also importers from Asia and Europe. Mueller actually led an industry effort to get tariffs and anti-dumping duties placed on Chinese, Mexican, and Vietnamese copper tube imports to protect domestic manufacturers. These trade protections have helped limit low-priced foreign competition in recent years. (It’s telling that management specifically cites tariff policy as a key uncertainty, and they favour any “trade protections” that keep the playing field level .) If those tariffs are removed or circumvented, competition could intensify and pressure prices in Mueller’s core product lines.

Perhaps the biggest competitive threat is not another company but another material: PEX plastic piping. PEX is a flexible plastic tubing that’s cheaper and easier to install than copper in many plumbing applications (particularly residential water lines).

Over the past two decades, PEX has steadily taken share from copper in new home construction. Mueller ventured into PEX products (via its Heatlink acquisition), but ended up exiting that business in 2023. Now it focuses on copper and metal systems. The risk is that plastic continues to displace copper for plumbing and even some HVAC/refrigeration uses.

Mueller acknowledges that its tube and fitting products “compete with a large number of manufacturers of substitute products made from other metals and plastic”, which is code for PEX and similar alternatives.

The flip side is that copper isn’t going away entirely as it’s still preferred in commercial buildings, high-temperature applications, and wherever longevity is paramount. And certain products like refrigerant linesets for AC units still rely on copper (PEX can’t handle refrigerant or high pressure well). So Mueller can coexist with PEX, but substitution will cap its growth in some markets. It’s a key risk factor to monitor over the long run.

Competitors and Peer Comparables

One puzzle with Mueller has been its valuation gap versus peers. Mueller’s products overlap with several sectors (industrial components, plumbing supplies, HVAC equipment), and some of its peers trade at rich multiples.

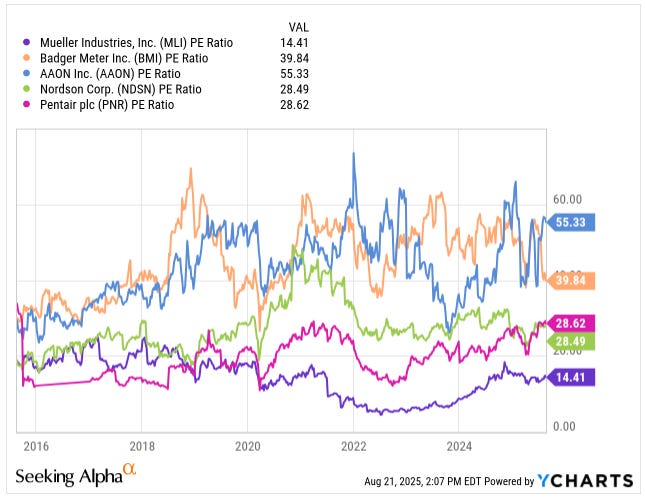

For instance, peers in water and flow control like Badger Meter (BMI 0.00%↑), AAON (AAON 0.00%↑), Nordson (NDSN 0.00%↑), and Pentair (PNR 0.00%↑) routinely trade in the high-20s to mid-50s P/E range. As of now, BMI is near 40x, AAON above 55x, and both Nordson and Pentair hover around 28x. By contrast, MLI sits at just 14x earnings, less than half of most peers.

The gap isn’t new: even back in 2022, when MLI was trading at ~8x, the multiple looked more like a cyclical metals processor than a water-infrastructure play. Investors have historically bucketed Mueller as a commodity copper tubing supplier (low margin, volatile) rather than a critical infrastructure enabler. Add in the fact that MLI doesn’t actively court Wall Street or push a growth narrative, and it has long been overlooked despite its stronger recent fundamentals.

When comparing, it’s worth noting Mueller’s peers often have more stable, recurring-revenue business models. BMI sells water meters with digital components, a more predictable business, hence a premium multiple. Watts (WTS 0.00%↑) sells specialized valves and controls; again, a bit more differentiated than a commodity tube.

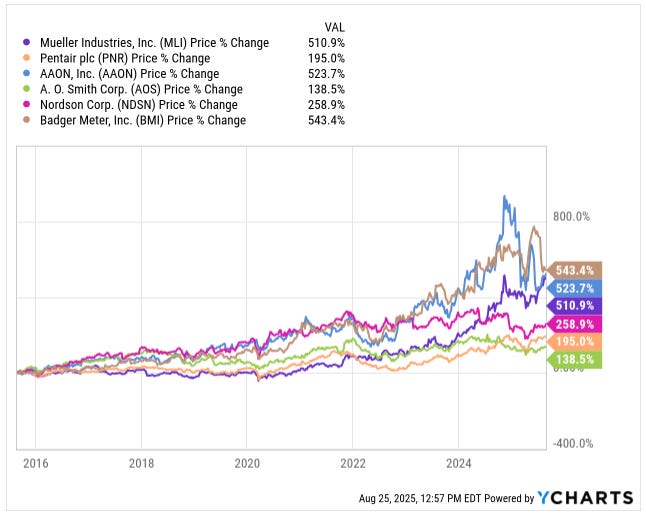

Mueller’s products, by contrast, are more basic and subject to commodity pricing, which historically justified a valuation discount. Yet its stock performance has been anything but discounted. Over the past decade, Mueller gained about 511%, nearly matching AAON (+524%) and Badger Meter (+543%), and far outpacing names like Pentair (+195%), Nordson (+259%), and A.O. Smith (+139%).

Sometimes the “boring” copper pipe-maker ends up being just as good (or better) an investment than the flashier, tech-enabled water and HVAC names.

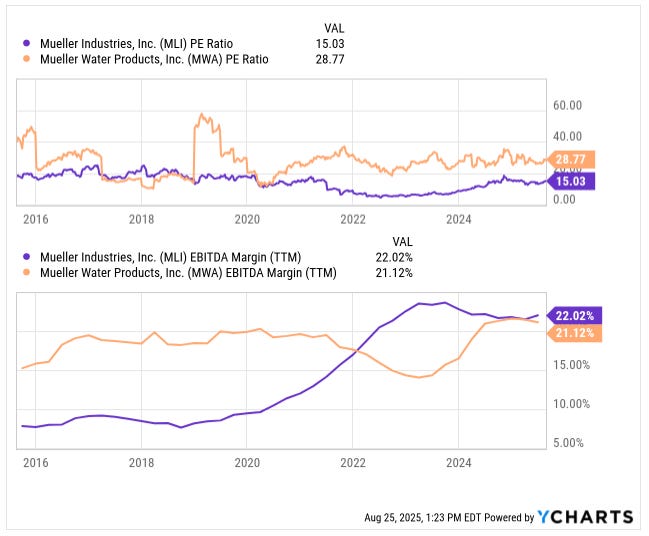

One more note on comps: there’s a similarly named company, Mueller Water Products (MWA 0.00%↑) (no relation aside from shared 1800s founder), that focuses on municipal water systems. That company trades at around 29x earnings and has similar margins.

I mention this because on stock screens, sometimes MLI and MWA get confused. In any case, Mueller Industries (MLI) today stands out as a high-margin, cash-rich outlier in its peer group. The question is whether those margins justify an upward re-rating or if they will fall back in line.

Management Quality and Capital Allocation

I have a lot of respect for Mueller’s management, especially in how they’ve stewarded the business in recent years. Greg Christopher has been at the helm since 2008 (and with Mueller since the 90s). He’s overseen the company’s transformation from a sleepy manufacturer to a lean, cash-generating machine.

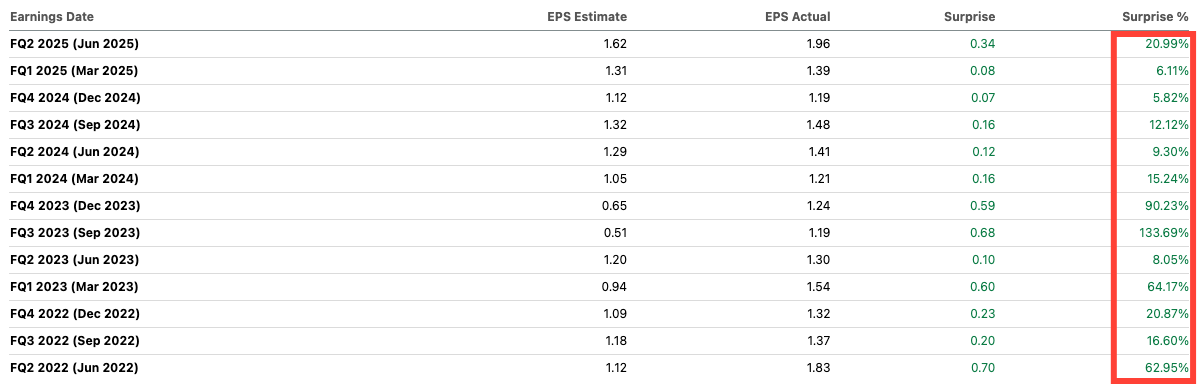

This management team is operationally savvy as they kept costs down, divested underperforming units, and scaled up the winners. The result was record earnings year after year, even through volatile conditions. In 2021 and 2022, they didn’t miss the chance presented by strong demand: Mueller’s plants ran full tilt, and the company delivered an “earnings streak” that impressed even the street.

One hallmark of quality management is capital allocation, and here Mueller shines pretty well. First off, the balance sheet discipline is excellent: Mueller carries effectively zero debt and has instead amassed over $1 billion in net cash by Q2 2025.

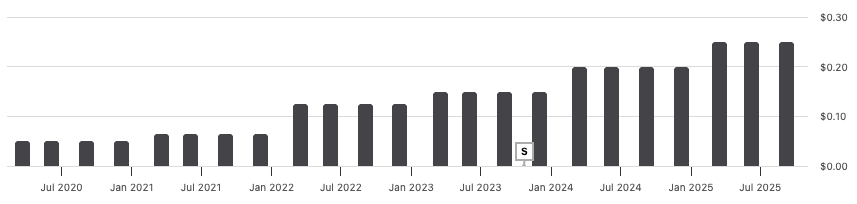

This gave them huge flexibility. They chose to reward shareholders directly. In early 2021, Mueller hiked its quarterly dividend from 10 cents to 13 cents and has since kept increasing it.

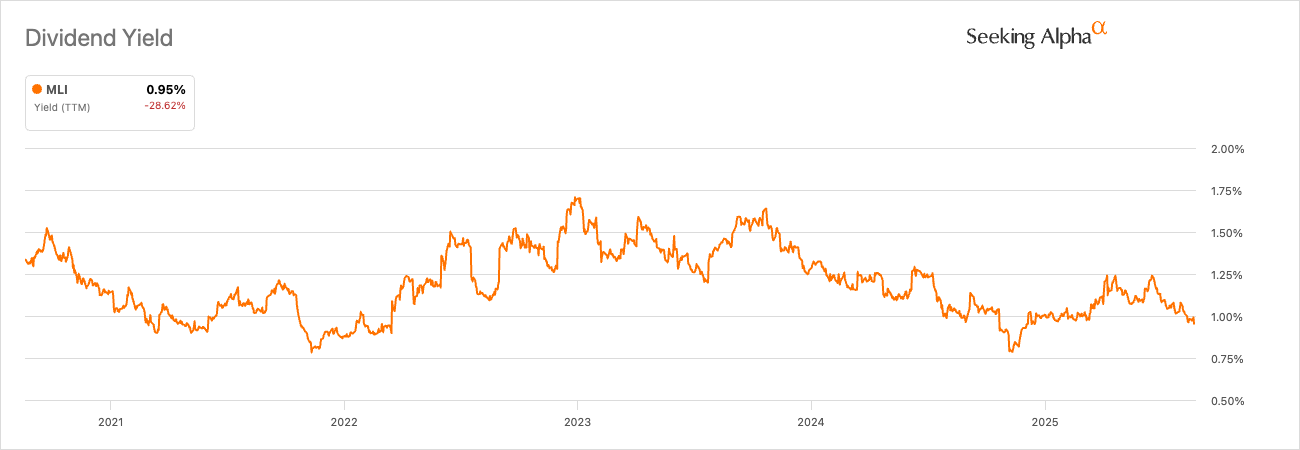

It’s not a massive yield (~1%).

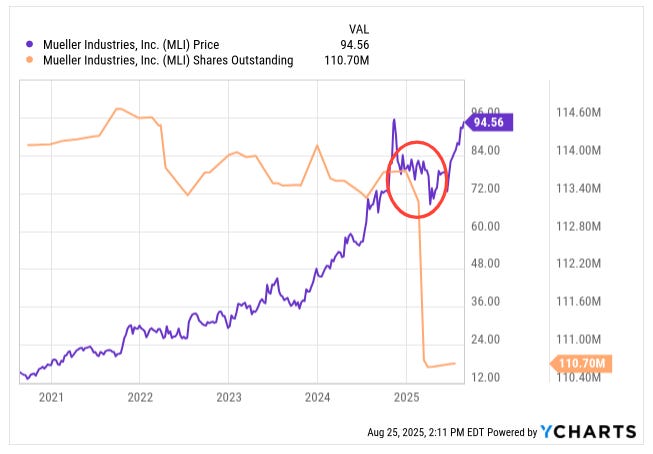

More impactful, they leaned hard into buybacks. For years, the share count hovered around 114 million, drifting only modestly. But in early 2025, management took a big swing.

Shares outstanding fell sharply to about 110.7 million, a drop of more than 3 million shares in just a few quarters. That’s nearly a 3% reduction in under a year, a meaningful cut for a company of this size. The buybacks coincided with a period when Mueller’s stock had pulled back into the $70s, which made each repurchase highly accretive. Rather than hoarding cash, management acted decisively, shrinking the share base at attractive prices and boosting long-term per-share value.

At the same time, Mueller didn’t just hoard or return cash; they also made smart acquisitions to bolster growth. The Nehring Electrical Works deal in 2024 is a good example. They paid $575M (in cash) for a business with ~$400M in revenue, expanding into electrical cables.

It wasn’t a bargain-basement price, but strategically it diversified Mueller and tapped into secular growth areas. Similarly, they bought Elkhart Products (EPC), a copper fittings maker, to consolidate more of the copper value chain. These acquisitions were funded from cash on hand, and Mueller still ended up with over $500M net cash post-deals.

That is prudent M&A: buying things that fit the core business and can be integrated, without betting the farm or leveraging up. So far, management reports that Nehring and EPC are contributing nicely.

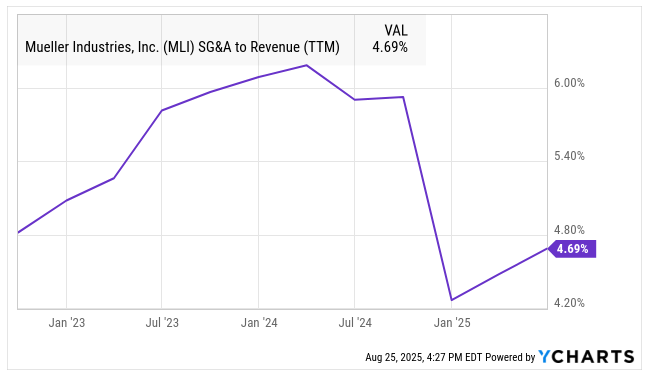

The culture at Mueller appears to be cost-conscious and pragmatic. The fact that they kept net margins rising and SG&A in check (SG&A actually fell as a % of sales in 2024) speaks to execution.

They’ve also maintained manufacturing efficiency. For example, even as copper volumes dipped in 2023, they managed to hold gross margins of ~29%.

That takes skill (and some luck from FIFO). I also note that Mueller’s current ratio is extremely strong (near 5x) and they have $1.0B cash with basically no debt. This conservative balance sheet suggests management doesn’t overextend. They like having a war chest for tough times or opportunistic buys.

On the Investor Relations front, Mueller has been traditionally low-key. They don’t appear on many conference lineups or CNBC segments. In fact, part of the opportunity was that few analysts followed it. Recently, though, I’ve seen signs of change. The company rolled out an investor presentation in 2024 and seems to be opening up a bit. (They even added a role focusing on industry/investor relations in 2025.) This could help close the valuation gap if more folks catch on to the story.

But they still have a long way to go. For example, Mueller doesn’t host earnings calls, and I don’t see them at conferences. In one sense, that’s a drawback. In another, it’s good discipline: management isn’t burning hours preparing quarterly decks and rehearsing scripts. Having been in corporate finance myself, I know how much leadership time those routines eat up.

One cautionary sign: insider selling.

The CEO himself sold a large block (100,000 shares) in August 2024 at around $70, and since then, directors and executives have sold additional shares as the stock climbed. Insiders have sold over $21 million in the last year, with zero open-market buys. The Chief Manufacturing Officer, for example, unloaded sizable chunks throughout 2025 at prices in the $75–82 range.

Insider selling doesn’t automatically mean a stock is overvalued. But the uniform pattern of selling and no buying tells me that those closest to the business believe the current price is at least a fair value, if not a bit rich. It’s something I factor in: management, while executing great, seems to view the stock as more of a source of liquidity now than a screaming bargain. That aligns with my analytical conclusion as well.

Valuation: Is There Upside Left?

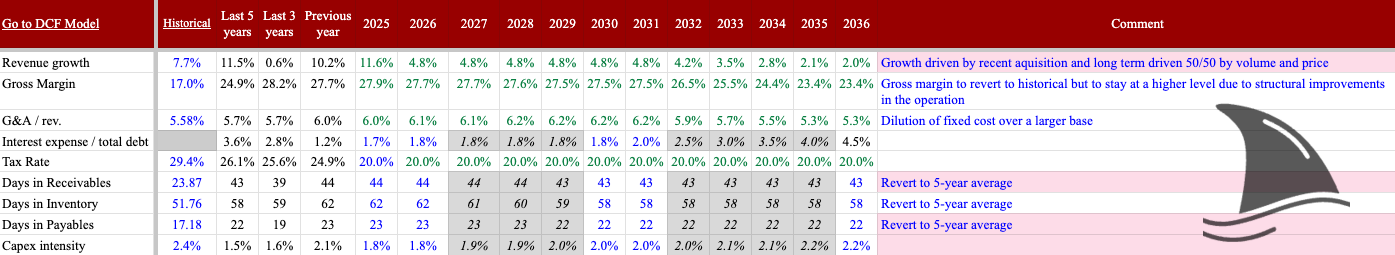

Given the cyclicality, I opted to do a conservative DCF valuation for Mueller, essentially assuming partial mean-reversion of those juicy margins. My DCF (base case) yielded a fair value of around $109 per share. That’s roughly 16% above the recent trading price. In other words, the stock looks modestly undervalued but not a screaming buy.

Here’s the breakdown of my thinking:

Revenue

I assumed mid-single-digit growth over the next decade (after an 11–12% bump in 2025 from acquisitions). These factors in some pricing normalization (as copper prices moderate), but continued volume growth in line with GDP/inflation. Essentially, Mueller grows a bit faster than the economy when including modest pricing power. There’s potential upside if we get an infrastructure super-cycle, but I didn’t want to bank on that.

Gross Margin

This is the crux. Historically ~17%, recently ~28-29%. I assume it settles around ~27–28% in the coming years, then gradually slips to ~23–24% by the 2030s.

Why not back to 17%? Because I do think some improvements are structural. Mueller’s operations are more efficient now, the product mix has shifted to slightly higher value items, and industry consolidation (plus tariffs) has reduced cutthroat competition.

So I give them credit for a “new normal” gross margin above old levels, but below the peak we just saw. In short, I model margins reverting, but not all the way.

This is the key point: investors may be extrapolating Mueller’s recent 27–28% gross margins as if they’ll last forever, but I’m modelling a more realistic ~24%. That gap in steady-state profitability makes a big difference in valuation. It’s why my fair value isn’t much higher than the stock today. If I assumed margins stayed at peak levels, sure, the upside would look huge but that’s not how I see it playing out.

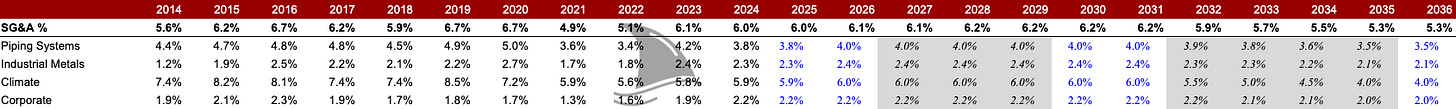

SG&A

Mueller has kept SG&A around 5–6% of sales. I projected a similar level, maybe ticking up slightly if revenue growth slows (some operating leverage reversal).

They don’t spend much on R&D (not a tech company), and I expect them to manage overheads well, as they have been.

Cash taxes

Mueller’s tax rate has been ~25-26%. I used 20% going forward, considering the benefit of higher R&D tax credits and perhaps more earnings in lower-tax jurisdictions. This might be slightly optimistic, but even at 25% it doesn’t change things hugely.

Capex and Working Capital

I assumed capex stays in line with historical, and working capital needs scale with growth (somewhat offset by the fact that as growth normalizes, inventory won’t be ballooning like it did in the inflation spike).

In 2022-2024, Mueller had to put a lot of cash into working capital as prices rose, but that should stabilize or even reverse if copper prices ease. Overall, I don’t foresee major capex. Mueller has plenty of capacity and just upgrades as needed.

Discount rate

I used a WACC of 8.6%, based on a cost of equity of about 11.3%, a cost of debt of 3.6%, and an assumed 35% debt-to-capital ratio. Mueller currently carries no net debt, but I view 35% as a sensible long-term optimal structure.

Management has shown itself to be rational: buying back shares opportunistically, raising the dividend, and pursuing acquisitions carefully. Eventually, I expect they will recognize the benefits of introducing some modest leverage. Using this capital structure, the NPV of future cash flows supports a stock price of around $109. At that price, Mueller would trade at roughly 15x my normalized earnings estimate of $7.25 EPS.

Key Risks

Every investment comes with risks, and Mueller is no exception. Below are the three main risks, in my opinion.

Margin Reversion

I’ve harped on this because it’s pivotal. Mueller’s recent gross and operating margins are way above historical levels. There’s a risk they could revert more sharply or sooner than I assume.

For instance, if gross margin fell back not to 24% but to 17% (the old normal) due to pricing pressure or cost increases, Mueller’s earnings would compress significantly.

Some investors may be assuming today’s elevated margins are permanent, but history says otherwise. Any hint of reversion (say, in quarterly results) could hit the stock. We already saw a partial pullback in 2023, and if 2025–2026 brings more normalization, the reaction could be sharp — especially if it overshoots to the downside.

In a severe case, if demand drops and copper prices fall simultaneously, Mueller could experience a double whammy: lower sales and FIFO turning into a margin headwind (selling high-cost inventory at low prices).

Cyclical Demand Risk

As discussed, Mueller is tied to construction and manufacturing cycles. A deeper housing downturn or recession would hurt volumes. We’re already in a slower housing market; if interest rates stay high or go higher, new construction could remain depressed for years.

Commercial construction is also tepid (lots of office and retail weakness). Roughly half of Mueller’s business is tied to residential and half to commercial, so it’s diversified, but both segments face macro headwinds right now.

The risk is that 2024-2025 might be a local peak in earnings, and a cyclical downturn could cause a year or two of declining sales/profits. The company itself noted demand is pent-up but won’t really increase until rates come down. If that’s 2+ years out, Mueller might hit an air pocket in between.

Substitution Risk (PEX & Others)

Over the longer horizon, the encroachment of PEX plastic piping could gradually shrink Mueller’s addressable market in residential plumbing. If copper tube demand declines faster than expected due to builders overwhelmingly choosing PEX (or other materials like CPVC, etc.), Mueller’s core Piping segment might stagnate or contract. The company would have to rely on other products to grow.

So far, PEX has taken a chunk of the low-end market, but copper is still used in upscale homes and many retrofits. This is a slow-moving risk, but real.

Additionally, in the Industrial segment, aluminum or composites could replace brass/bronze in certain applications if weight or cost is an issue.

Climate segment could see alternative technologies (e.g. aluminum coils instead of copper coils in HVAC). Mueller has some capabilities in those materials, too, but copper is its bread and butter.

Catalysts and What to Watch

On the flip side, what could go right or drive upside for Mueller? There are a few things I’m watching:

Housing & Construction Rebound

Perhaps the most straightforward catalyst: if interest rates ease (or the economy adapts to higher rates) and housing starts pick up materially, Mueller would see a nice boost in volume. There’s a lot of pent-up demand for housing in the U.S.

New home construction has been below what’s needed for population growth. Should we get a resurgence in homebuilding (or retrofitting, thanks to maybe infrastructure bills or climate-related upgrades), Mueller’s plumbing and HVAC products would be in high demand. Even a stabilization at a healthy level of housing starts would be good – it removes a headwind.

Infrastructure Spending & Electrification

Mueller is positioning for secular trends in infrastructure. Its water infrastructure and climate comfort focus give it exposure to any government or private spending on replacing aging water pipes, improving HVAC efficiency, etc. The big one is the electrical grid modernization. With Nehring, Mueller is now supplying wire and cable for utility and telecom uses.

As the U.S. upgrades the grid for renewable energy and builds out EV charging networks, that’s a tailwind for copper wire demand. Nehring could see significant growth if, for example, utilities invest heavily in transmission lines (which need a lot of copper/aluminum cable).

There’s also the ongoing data center boom. Data centers use tons of cable and HVAC equipment, which touches multiple Mueller segments (wires, valves, fittings, heat exchangers). These trends are likely to play out over years, not overnight, but they provide a growth avenue beyond normal construction cycles.

M&A or Strategic Actions

Mueller’s strong balance sheet means it could continue making bolt-on acquisitions. The company could scoop up a complementary business (perhaps a plastic fittings company to hedge the PEX risk, or another electrical component maker) to bolster growth. Conversely, Mueller itself could attract interest from a bigger player or PE firm.

Continued Share Buybacks

This is more internally driven, but if Mueller keeps retiring shares at a good clip, it will boost EPS and potentially the stock price. They still have authorization left on their buyback program. With $1B cash, they could easily do another accelerated repurchase if they don’t find other uses.

Margin Persistence

If Mueller’s margins don’t revert as much as I expect, that’s upside. It could be that the structural changes (consolidation, tariff protection, product mix) allow it to hold 25-30% gross margins for much longer.

Investor Awareness

As trivial as it sounds, sometimes a stock gets a boost simply from more people discovering it. Mueller has started to show up on value investors’ screens due to its strong performance. If a major investing newsletter (aside from this one!) or a big hedge fund takes a stake and publicizes the thesis, the stock could see renewed interest.

It has already risen a lot, but at a $10B market cap, it’s still small enough for many funds to accumulate if they believe in the story. Improved investor relations (presentations, conference appearances) could incrementally help here.

Operational Excellence / Cost Improvements

Internally, if Mueller can further streamline operations, such as automating more processes or optimizing its supply chain, it might offset margin pressures. They recently consolidated some facilities and sold non-core assets (like a French copper tube operation in 2021).

If they continue to seek out efficiencies, it could surprise to the upside on earnings. Given how well they did in recent years, I suspect a lot of low-hanging fruit is already picked, but this team isn’t resting.

Verdict: A Good Business, But I’m Not Biting

After this deep dive, I come away impressed with Mueller Industries as a business. It’s rare to find a 100-year-old manufacturer with no debt, high returns on capital, and management that consistently “does the right things”.

Mueller’s execution over the past few years has been excellent, turning a commodity price surge into a cash windfall and long-term improvements. This is a case study of a “boring” company that rewarded shareholders handsomely. In many ways, Mueller exemplifies the kind of under-the-radar, high-quality stock I love to find.

I love the company; I just don’t love it at +$90. A 16% anticipated gain (to $109 fair value) doesn’t compensate for the risks I outlined. In fact, the stock has already rallied 26% in the last three months (perhaps on optimism that the worst of housing is over).

The easy money has likely been made. Future gains will require either continued stellar performance or multiple expansion. Both are possible, but I’m not confident enough to bank on them.

I’ll keep Mueller on my watchlist. If the stock pulls back into the $60s or if fundamentals improve even more than expected, I’d revisit it. But for now, I’m content to let this one go and seek better risk/reward elsewhere. As the saying goes in my newsletter’s spirit, we aim to beat the tide, and here the tide of market optimism might be a bit too strong for my comfort.