Oil-Dri Corporation of America (ODC) Deep Dive: The Dirt on a Quiet Compounder Hiding in Plain Sight

This vertically integrated U.S. manufacturer owns its raw materials, controls its entire supply chain, and could actually benefit from tariffs.

Update:

Oct12’25: Q4 2025 earnings result

Sep7’25: Closed position @ $68.28, a 57% gain in 5 months (rationale & updated valuation)

This idea played out faster than expected. If you want access to my next high-conviction ideas with +50% potential, consider upgrading to paid.

What I’m about to say might trigger a few of you to unsubscribe…but here it goes:

I’m not a cat person.

I don’t hate cats, but I wouldn’t own one. They’re too snobby for me. I’m a dog person. Sure, they’re high maintenance, but the companionship and unconditional love? Unmatched. Even by us humans.

This is Nagnush. He enjoys sunbathing.

And this is Shaquee, he loves swimming.

But when it comes to investing, I leave the pet preferences at the door. I’m not here to chase ESG darlings or avoid so-called “sin stocks.” I’ll invest in anything that prints cash even if it’s tied to feline bathroom habits.

So when my stock screener flagged a company that sells cat litter as a potentially great investment, I didn’t scoff. I leaned in. And what I found was a lot more compelling than I ever expected.

This company is exactly the kind of under-the-radar, boring-on-the-surface business that value investors dream about. It’s been quietly building a vertically integrated empire around sorbent clays, not just for litter boxes but for everything from oil purification and industrial cleanup to farm fields and animal health. And that boring clay? Turns out it’s a surprisingly good business when you control the entire supply chain.

Oil-Dri Corporation of America (ODC 0.00%↑) owns hundreds of millions of tons of its own mineral reserves, mines them in the U.S., processes them in company-owned plants, and sells the end products under both house brands and private labels. It serves a mix of resilient, cash-generative markets (pet care, industrial absorbents, edible oil processing, and even baseball fields) where its clays either absorb liquid like a sponge or adsorb impurities like a Brita filter. The company’s edge comes from this mine-to-shelf integration, plus decades of product development and embedded customer relationships.

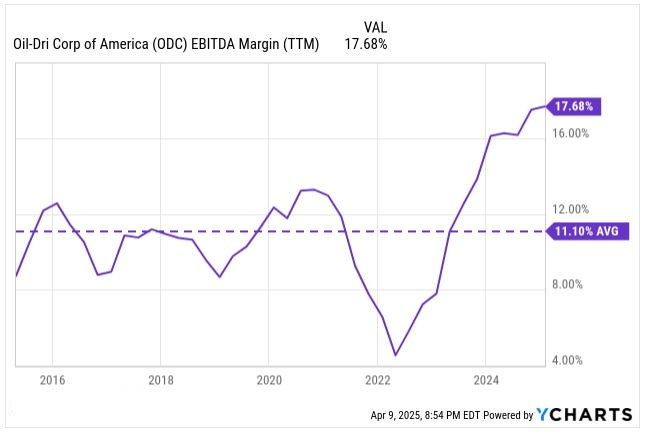

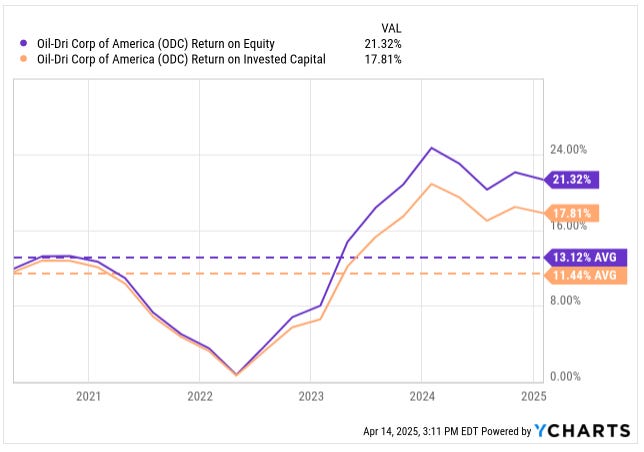

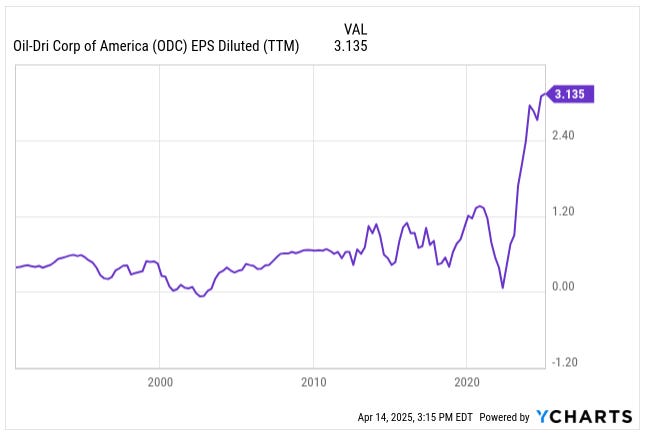

But what’s really exciting is how ODC has been shifting its mix toward higher-margin, value-added products. In the last few years, ROE and ROIC have taken a step up, and earnings per share have more than tripled from sub-$1 levels to $2.72 in 2024 and $3.13 TTM. EBITDA margins are rising, cash flow is strong, and the balance sheet remains conservative even after acquiring Ultra Pet to expand into silica gel crystal litter, a premium segment previously dominated by imports.

Speaking of imports, the recent wave of “Liberation Day” tariffs might play right into ODC’s hands. This is a domestic producer that mines and manufactures in the U.S. so any increase in duties on foreign clay or litter gives ODC a pricing edge. Add in the possibility of modest financial leverage or buybacks (something the Jaffee family could use to convert Class B shares into higher-dividend common stock), and you’ve got optionality that isn’t priced in.

Yes, there are risks. Walmart (WMT 0.00%↑) is a 20% customer, natural gas is a key input, and some of the company’s clay reserves sit on federal land. But these are known, manageable, and frankly outweighed by the upside. The Jaffee family, who controls the company through a dual-class structure, has run it conservatively for decades. That stability, paired with hidden strategic assets and a growing moat, makes ODC the kind of compounding machine that doesn't scream for attention but quietly delivers.

At $64 per share fair value by my DCF, I think the stock is still undervalued. If you want the full breakdown from how the clay works, how the products are made and how the family structure influences capital allocation, it’s all here in the deep dive. But even if you stop here, know this: Turning dirt into dollars isn’t just clever marketing, it’s the real story behind Oil-Dri.

Table of contents:

What Are Sorbent Clays? A Simple Guide to the Science Behind the Business

Revenue Breakdown: How This Specialty Minerals Company Makes Money

From Mine to Market: Oil-Dri’s Clay Mining and Manufacturing Process

Competitive Advantages: Vertical Integration, Raw Material Control, and Product Depth

Financial Performance: Rising Margins, ROE, and Free Cash Flow Growth

Ownership Structure: Dual-Class Shares and the Jaffee Family's Long-Term Control

Industry Landscape: Competitors in Pet Care, Industrial, and Agricultural Clays

The Clorox Relationship: Strategic Partner, Customer, and Boardroom Influence

Valuation Analysis: DCF, Margin Expansion, and Long-Term Upside

Conclusion: A Boring Business with Dirty Work and Clean Profits

The Science of Sorbent Materials (Clay 101 in Plain English)

ODC’s entire business revolves around sorbent materials. Essentially, special clays that either absorb or adsorb liquids.

What’s the difference?

Think of it this way: absorbent materials act like a sponge, soaking up liquid into tiny pores, while adsorbent materials act more like a magnet or filter, attracting and binding impurities to their surface. ODC deals in both kinds. Its products are made mostly from “Fuller’s Earth” clay minerals, things like calcium bentonite and attapulgite (a type of clay), which it mines. These clays naturally have a huge surface area and lots of tiny pores. If you magnified a grain of ODC’s clay, it would look like a sponge or honeycomb – all those nooks and crannies can trap liquids.

Absorbents = clay sponges: ODC’s absorbent clays suck up liquids into their pores. For example, their traditional cat litter and floor dry products drink in urine or oil spills, locking the liquid inside. Hundreds of little air pockets inside each clay granule can fill with fluid, just like squeezing water into a sponge.

Adsorbents = clay magnets: Other ODC products are adsorbent, meaning they chemically attract certain unwanted molecules out of liquids. A good analogy is a Brita water filter pulling out impurities. ODC’s adsorbent clays (often used in purification) bind things like metals, colours, or surfactants to the clay’s surface. The impurities stick to the clay as the liquid passes by.

In short, these special minerals can either soak up big volumes of liquid or selectively grab impurities, capabilities that turn out to be incredibly useful in many industries.

It’s not high-tech nano-material, but it works wonders in practice (if you want to see what is high-tech nano material, check my TSMC deep dive as I go super duper deep into semiconductors). And, crucially, ODC controls its own supply of these minerals from the ground to the bag.

From Mines to Markets: How ODC Makes Money

ODC might have started in the 1940s selling clay floor absorbents for garages, but today it has a diversified range of products. The company breaks its business into two main segments: Retail & Wholesale (selling through stores, online, and distributors) and Business-to-Business (selling to manufacturers).

However, it’s easier to understand by looking at their major product groups. Let’s tour each of ODC’s key product categories and see what they are and how they generate revenue:

Cat Litter Products: Turning Clay into Kitty Comfort

Cat litter is ODC’s flagship product and perhaps the most relatable for consumers. If you’ve bought Cat’s Pride or Jonny Cat litter at the store, you’ve bought ODC’s clay in disguise.

The company produces two main types of litter: scoopable clumping litter and coarse non-clumping litter. Both use absorbent clay to trap moisture and odours, but scoopable litter has a twist as it forms clumps when wet, making it easy to scoop the “used” bits and toss them.

ODC was actually a pioneer in lightweight scoopable litter, creating a formulation that is up to 40% lighter than traditional litters. They achieve this lightness by using clay with naturally low density and by super-heating it to drive out moisture, which creates an airy structure.

ODC sells litter under its own brands (Cat’s Pride and Jonny Cat) and also produces private label litter for various retailers. If you buy a store-brand litter, there’s a good chance ODC made it behind the scenes. They even have a long-term deal to supply Clorox’s Fresh Step brand with coarse (non-clumping) litter, where Clorox handles marketing and ODC does the manufacturing. This co-manufacturing arrangement shows ODC’s strength in production as even a big household name trusts them to make the product.

In 2024, ODC expanded into silica gel crystal litter by acquiring a company called Ultra Pet. Those are the translucent crystal beads you might have seen, which aren’t clay at all but synthetic silica gel (similar to the desiccant packets in new shoes). Silica litter can absorb a lot of liquid and is very lightweight and low-dust. With the Ultra Pet acquisition, ODC now sells crystals under brands like Ultra and Litter Pearls, including private label versions, both in the U.S. and internationally. This move let ODC compete in a growing niche of the litter market that it previously had little presence in. (For years, most silica litter was made in China.)

How this makes money: Cat litter might seem low-tech, but it’s a consumer staple. ODC earns revenue by selling millions of bags and boxes of litter through grocery stores, pet stores, dollar stores, farm supply stores, and online retailers. Volume is driven by pet ownership trends.

In recent years, cat litter sales have been strong. ODC reported record revenues in its Retail segment, driven primarily by cat litter sales. They’ve also been able to raise prices when needed (e.g. to offset higher costs), since kitty litter is a relatively small expense for pet owners in the grand scheme.

With innovative products like a new EPA-approved antibacterial clumping litter launched in 2023 (the first of its kind in the U.S.), ODC even finds ways to differentiate and add value. Selling absorbent clay to millions of cat owners has become a lucrative, steady source of cash for ODC.

Agricultural & Horticultural Products: Helping Farmers Sow and Grow

The same absorbent clay that soaks up pet messes can also help farms and gardens. ODC produces a range of agricultural and horticultural products that are essentially clay granules used as carriers or conditioners for soil and farm chemicals.

What does that mean? Imagine you have a liquid pesticide or fertilizer. Rather than spraying it, you could attach it to dry clay granules, which are then spread on fields. ODC’s products Agsorb and Verge serve this purpose: they absorb the active chemicals and then release them into the soil more evenly and slowly than a liquid spray would. This allows for more precise application, less drift, and often better results for crops. Verge granules are engineered to be uniform balls with very low dust, which farmers appreciate.

Another product, Flo-Fre, is a microgranule added to grain or seed storage to soak up excess moisture and prevent clumping or caking. If you’ve ever had salt clump in a shaker due to humidity, you get the idea. Flo-Fre keeps big silos of grain nice and dry. These agri-products are sold by ODC’s technical sales force mainly in the U.S. for uses in row crops, turf management, lawn and garden, etc. They’re a smaller piece of the business but add a nice niche revenue stream.

How this makes money: ODC earns income by selling these clay-based carriers to agricultural chemical companies and directly to large farming operations. The clay itself is inexpensive (coming from ODC’s mines), so the value here is providing a reliable, uniformly sized carrier that can improve the effectiveness of agricultural chemicals. As farming practices evolve (like more precise application of inputs), products like Agsorb and Verge fill a need. This product group’s sales can fluctuate with agricultural market conditions (farm incomes, planting acreage, etc.), but generally, it’s a steady business. It doesn’t grab headlines, but absorbing moisture and carrying chemicals for agriculture is another way ODC monetizes its clay.

Fluids Purification Products: Filtering Food Oil, Fuel and More

One of ODC’s coolest applications (to a science nerd like me, at least) is fluid purification. Here, their special clays act as adsorbents filtering and purifying liquids ranging from edible cooking oils to industrial oils. These products are often called “bleaching earth” or filter aids in the industry.

ODC’s brands, like Pure-Flo, Perform, and Ultra-Clear, are used by food processors to remove impurities from edible oils (think soybean oil, canola oil, etc.). When vegetable oil is extracted, it can have colours, odours, or trace metals that need to be removed to make clear, shelf-stable cooking oil.

Clay treatment is a key step: the oil is passed through ODC’s clay, which adsorbs unwanted pigments (like chlorophyll that makes oil greenish) and other trace contaminants. The result is a purified, “bleached” oil ready for bottling. Perform and Pure-Flo are tailored to different oil types. Some oils are harder to bleach than others, so the clay can be optimized for higher “activity” to grab impurities.

ODC has also developed specialty clays (Select, Metal-X, Metal-Z) for the growing renewable fuel industry. Renewable diesel and biodiesel (fuels made from vegetable oils or animal fats) need purification just like food-grade oils. For example, Metal-X and Metal-Z clays target the removal of metals during renewable diesel production. Ultra-Clear is used to purify jet fuel and other petroleum products. In all these cases, ODC’s adsorbent clay is acting like a purification filter – grabbing impurities that would cause problems (rancidity in foods or catalyst poisoning in fuel refining).

How this makes money: ODC sells these purification clays to processors of edible oils and biofuels around the world. This is largely a B2B business with technical salespeople working with refineries and factories. Volume is tied to how much oil is being processed. Notably, ODC saw fluids purification product sales jump ~19% in 2024, thanks in part to new customers in renewable diesel and strong demand in food oil markets. As the world uses more biofuel and cooking oil, the need to purify those at scale is growing, and ODC benefits from that trend. These products tend to have good profit margins too, because the value added by purification is high. ODC is one of only a few players globally with the right clay resources and know-how to supply this market, giving it a defensible niche.

Animal Health & Nutrition: Keeping Livestock Healthy with Clay

Moving from oils to animals: ODC, through its Amlan International subsidiary, makes products that help keep livestock (like pigs, poultry, and cattle) healthy.

How can clay help a chicken, you ask? It turns out that certain clays can bind to toxins and pathogens in animal guts. ODC’s Calibrin line of feed additives, for example, can bind mycotoxins, nasty moulds that sometimes grow on feed grains, so that a cow or pig doesn’t absorb those toxins but passes them harmlessly.

In simpler terms, the clay additive acts like a detox sponge in the animal’s digestive tract. Products like Varium and NeoPrime (marketed internationally) or Sorbiam (in North America) are used to improve gut health and growth in poultry and swine by binding pathogens and modulating the gut environment.

Another product, MD-09 Moisture Manager, is fed to chickens to reduce wet droppings (yes, drier chicken poop – glamorous, I know). Drier litter in poultry houses means healthier chickens and less ammonia, a clear benefit to farmers. ODC also sells Pel-Unite binders that help form sturdier pellets in animal feed.

These animal health products are often feed additives mixed in at feed mills, and ODC sells them worldwide via distributors and its own small sales teams in places like China and Mexico. It’s a smaller but potentially high-growth part of the business as the livestock industry looks for alternatives to antibiotics and chemicals to keep animals healthy. Clays offer a natural solution.

How this makes money: ODC earns revenue by selling these value-added additives to livestock producers and feed companies. While the clay itself is cheap, the technical benefits (binding toxins, improving animal weight gain, etc.) allow ODC to command a good price for specialty products. They even use contract processors to make some of these additives with proprietary formulas. The business has been challenging at times.

For instance, a few years ago, African Swine Fever in Asia drastically reduced the pig population, cutting demand for feed additives. ODC’s animal health sales were flat in 2024 overall. But in the long run, as global protein demand grows, these natural clay-based solutions have a place. It’s another example of ODC finding a unique way to monetize its clay. And like other B2B lines, success here builds on research and field trials, essentially selling proven science to farmers.

Industrial & Automotive Products: Absorbing Oil Spills and Shop Messes

This is ODC’s original business: absorbents for industrial cleanup. If you’ve seen those bags of oil dry or garage floor absorbent at auto shops, that’s the stuff.

ODC manufactures granular clay absorbents that soak up oil, grease, paint, chemicals and water from floors.

Spilled a quart of motor oil in your garage?

Throw down ODC clay granules, let it soak up, then sweep it away.

The clay provides a non-slip, non-flammable way to deal with slick spills, which is why it’s a staple in factories, mechanic shops, and even home garages. These products are often literally called Oil-Dri floor absorbent (the brand name became a generic term, like “Kleenex” for tissues). They sell them in various grain sizes and packaging to industrial distributors.

In addition to clay granules, ODC also offers synthetic sorbents – things like polypropylene pads, rolls, socks, and booms that soak up oil spills. You’ve probably seen those white absorbent mats or long “sausages” used to contain oil leaks; ODC produces a line of those as well (sometimes using recycled materials, too). While the clay absorbents are great for routine shop spills, the poly sorbents are used for larger spills or where you want to float an absorbent on water (e.g. an oil spill in a harbour). They package these into spill kits for emergency response and sell them through safety supply distributors.

How this makes money: This line is a classic volume business. ODC sells bulk absorbent to a wide range of customers via distributors in industrial supply, auto parts stores, janitorial supply, etc. The demand is steady. Wherever there is machinery, maintenance, or vehicles, spills happen and need cleaning. The products are low-cost consumables, so customers reorder regularly. It’s not a high-growth market (it’s quite mature), but ODC has a strong market share in North America due to its long history and trusted brand.

Essentially, they monetize clay (and some polypropylene) by solving a liability and safety problem for businesses: spilled oil on a factory floor is both dangerous and regulatory trouble if not handled. This part of the business is typically stable and generates solid cash. It’s also closely tied to general economic activity. More manufacturing and driving mean more spills to clean. Over the years, ODC’s industrial products have been a cash cow that helped fund the company’s expansion into fancier things like cat litter and animal health.

Sports Field Products: Keeping Fields Dry and Playable

Rounding out ODC’s portfolio is a neat niche: sports field products. Under the brand Pro’s Choice, ODC sells specialty clay products used on baseball and softball fields, as well as other sports turf. If you’ve ever watched an MLB game after rain, you might have seen the grounds crew spread drying agent on the infield that’s likely a clay product like ODC’s Rapid Dry.

These clay granules wick away excess water from muddy infields so the game can resume faster. ODC also produces soil conditioners that are mixed into the top layer of ballfields to improve drainage and prevent compaction. Another product, Pro Mound clay, is a specialty packing clay for building pitcher’s mounds and batter’s boxes that hold up under wear. These products are used from professional MLB stadiums down to local little league and municipal fields. Many big league fields rely on them to maintain ideal playing conditions.

How this makes money: While a relatively small segment, ODC’s sports turf products generate revenue by solving a critical problem for sports: rain and wear-and-tear on fields. They are sold through distributors of sports turf supplies and directly to field managers. The business can be seasonal (lots of sales in spring and summer). ODC leverages its clay’s natural absorbency and ability to improve soil structure. It’s taking that same absorbent clay and repackaging it to “dry the field” or “keep the mound solid.”

Given the passionate market for sports and the importance of field quality, teams and schools are willing to pay for these conditioners. While not huge in dollar terms, it underscores ODC’s strategy of finding multiple markets for its core sorbent minerals.

Those are the big buckets of ODC’s business. Remarkably, all these diverse products trace back to the same fundamental raw material (absorbent clay) just processed and purposed in different ways. From cat litter to canola oil refining to keeping a pitcher’s mound pristine, ODC has found ways to make itself useful (and make money) across the board.

Next, let’s look at how ODC actually gets this clay out of the ground, turns it into saleable products and why its control over its raw material is such a competitive advantage.

From Clay Pit to Product: Mining & Manufacturing Process

ODC doesn’t buy its clay from some third party. It mines 100% of it from its own reserves. This vertical integration is at the heart of the company’s strength. ODC operates surface mines in several states (Mississippi, Georgia, Illinois, California) located conveniently near its processing plants. Their active mines are at most 11 miles away from the processing facilities, and some are adjacent.

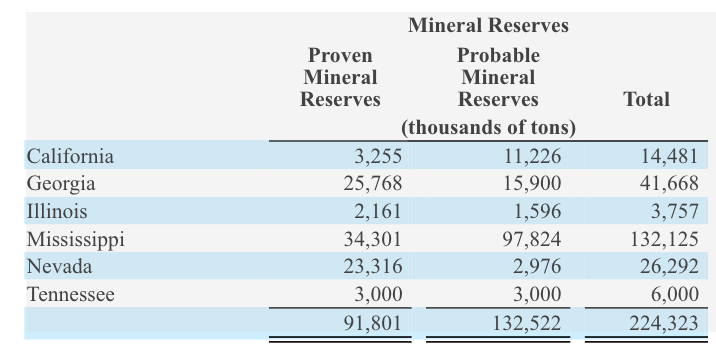

This was not by accident: the company strategically acquires mineral-rich land and sets up plants next door. As of mid-2024, ODC had proven and probable clay reserves of about 224 million tons. That’s enough clay to supply over 40 years of production at current usage rates.

They even have additional reserves, identified in places like Nevada and Tennessee, held in their back pocket for future use. In short, they’re sitting on a mountain (or several) of absorbent clay.

Mining the clay

ODC uses open-pit surface mining, which is like giant-scale strip mining. If you are curious about what open-pit mines are and want to see the biggest open-pit mines in the world, check out this video.

They first remove the “overburden”, the layer of soil or rock covering the clay seam, using heavy machinery (bulldozers, scrapers, excavators). Once the clay layer is exposed, they dig it out with loaders and excavators. Huge off-road dump trucks then haul the raw clay to the processing plant nearby.

This happens year-round, and ODC does it with a mix of its own crew and some contractors. Because the mines are so close, the haul is quick and efficient. Each plant keeps about one week’s worth of raw clay stockpiled on-site as a buffer. The company also employs geologists to continuously evaluate and explore the deposits to ensure quality and that they maintain at least ~40 years of reserves. This long-term approach to securing raw material means they’re never scrambling for clay. It’s a huge peace-of-mind factor for the business.

Processing the clay

Once at the plant, the clay goes through several steps to turn it into the final products. While specifics can vary, generally, the process includes crushing the clay chunks, drying them, and sizing or granulating them into the right form.

A key step is the drying, which ODC does in large rotary kilns or dryers heated by natural gas (or fuel oil). They essentially bake the clay to remove moisture. In fact, their process can remove 97% of the moisture from the clay, which greatly increases its absorbency and reduces weight. It’s like baking out all the water; a dry sponge can absorb way more than a damp one.

This thermal processing is energy-intensive but critical. For some products (e.g. certain absorbents), they might also heat-treat or “activate” the clay at higher temperatures or with additives to enhance its absorption/adsorption properties. After drying, the clay is milled or granulated to different particle sizes: fine powders for purification clays, intermediate granules for cat litter, larger granules for floor absorbents, etc. They use sifters to separate sizes and may treat the clay with minor additives depending on the product (for example, adding baking soda or scent to cat litter or binding agents to make clumping litter clump).

Finally, the products are packaged, which could mean 20-pound bags, 50-pound sacks, shrink-wrapped palletized bags, small jug containers for retail, bulk totes, etc., depending on the customer. ODC’s facilities are essentially part mining operation, part factory, and part packaging plant. They’ve been refining this process for decades, which gives them a cost advantage. The low bulk density of their clay (thanks to its porous nature and thorough drying) even allows them to sell “lighter” weight bags with the same volume, as highlighted by one product data sheet, a subtle marketing and freight advantage.

An example of the integrated process: at ODC’s largest plant in Georgia, they mine attapulgite clay locally, dry it in kilns using natural gas, and then bag it as lightweight Cat’s Pride litter that ships to Walmart’s and PetSmart’s distribution centers. The value added from a hole in the ground to store shelf all accrues within ODC. Contrast that with competitors who might have to buy clay from miners; ODC earns the miner’s margin, too. It’s vertically integrated in a similar spirit to how a steel company might own iron ore mines. Owning their raw material supply and processing it in-house is a cornerstone of ODC’s business.

One more point: because they own the mines, the clay on their balance sheet is carried at cost, which is very low (just land acquisition cost). Only acquired reserves show up with a value (and those are small). So there is a lot of hidden value (literally mountains of clay) not fully reflected in the accounting books. It’s not gold or lithium, sure, but it’s of strategic value because it ensures the company isn’t beholden to external suppliers.

Energy Inputs and Cost Hedging: Managing the Fire that Dries the Clay

Turning wet clay into the ultra-dry, fluffy stuff that ODC sells requires a lot of heat. The company primarily uses natural gas to fire its kilns and dryers. Energy (natural gas and, in some cases, fuel oil where gas isn’t available) is one of ODC’s biggest production costs outside of labour. If gas prices spike, ODC’s costs go up significantly, which in turn pressures profit margins if they can’t pass it to customers.

To manage this, ODC employs a hedging strategy: it locks in forward contracts for natural gas for a portion of its needs. Essentially, they pre-buy or fix the price of gas for future months to dampen the volatility. During fiscal years 2023 and 2024, for instance, ODC entered into forward purchase contracts for natural gas at its Georgia and California facilities, securing a chunk of supply out through fiscal year 2026. This kind of hedge is prudent. It’s like how an airline hedges jet fuel. ODC doesn’t hedge 100% of its gas, but they do enough to avoid nasty shocks.

This strategy paid off in 2024: Natural gas prices actually fell from prior highs, lowering ODC’s per-ton gas cost by 28% versus 2023. That helped improve gross margins significantly. It’s almost like they enjoyed a tailwind after a period of very high gas prices in 2022. Of course, these things can swing, but by hedging some portion, ODC smooths the ride. The company notes that it may also use other financial instruments at times to manage energy costs, and it keeps an eye on global events (a war or cold winter in Europe can send LNG prices up, etc.). They are well aware that energy markets can be volatile.

ODC also consumes electricity and diesel fuel (for mining equipment and forklifts), but natural gas is the big one. One advantage of having plants in places like Mississippi and Georgia is relatively cheap energy and favourable industrial rates. They even mention that volatile oil and gas markets can impact freight costs, too (diesel for trucks). In 2024, the domestic freight cost per ton rose for ODC, partly due to changes in shipping terms with a major customer and partly due to the addition of the Ultra Pet products (which have to be transported). But overall, operations benefited from lower fuel costs that year.

To summarize: energy is a critical input, and ODC mitigates this risk by

location: operating in the U.S. with decent energy infrastructure,

hedging: locking in prices on a chunk of usage, and

passing on costs: when possible, they raise their prices to offset sustained energy cost increases.

Being vertically integrated, they feel the cost directly but also can adjust pricing if competitors face the same issue. If energy costs soar, smaller competitors might suffer more than ODC (if they didn’t hedge or lack economies of scale), allowing ODC to potentially gain share or push through price increases.

One fun fact: During the fracking boom about a decade ago, natural gas in the U.S. became super cheap, which essentially gave a company like ODC a nice cost advantage (drying clay in America got cheaper). Should there be another period of ultra-low gas, ODC’s margins could expand. Conversely, a natural gas crisis would act like a tax on their production.

Competitive Advantages: Owning the Dirt (and the Plant Next Door)

From the above, it might already be clear what gives ODC an edge, but let’s spell out the competitive advantages that protect its business and profits:

Advantage #1. Ownership of Key Raw Material

ODC owns or controls all the clay it needs. This is huge. They are not at the mercy of suppliers or global commodity prices for their primary input as it’s literally under their feet.

With 40+ years of reserves locked up, they have long-term security. Owning the raw material means they capture that profit margin (they “pay” only the cost to mine it, which is low), and they can ramp up production without worrying about scarcity.

It also deters new competitors. You’d need to find and develop a similar quality clay deposit and build a mine/plant to truly compete, which is a high barrier to entry.

The Dirt Is Everywhere… But Still Hard to Copy

At first glance, it’s easy to underestimate what ODC owns. After all, clay isn’t rare. Attapulgite, bentonite, and other absorbent clays exist all over the world and in more than a few places across the U.S. So why aren’t more companies going toe-to-toe with ODC?

Finding clay is easy. Making it useful is hard.

Think of it like this: there’s gold dissolved in ocean water. Trillions of dollars of it. But there’s a reason no one’s mining it as you’d go broke trying to extract it. That’s kind of how it works with commercial-grade sorbent clays. The mineral might be “everywhere,” but:

It has to be the right composition (not all clay has good absorption or adsorption properties).

It has to be in a seam large and consistent enough to justify mining.

It has to be close to a processing facility (clay is heavy and expensive to haul).

And most importantly, you need the technical know-how to process, dry, granulate, and package it for different end uses.

ODC doesn’t just dig and sell dirt. ODC has spent 80+ years perfecting how to extract, dry, bake, grind, and shape these clays into premium products across multiple industries. From the texture of clumping litter to the pore structure for filtering vegetable oil, every use case has unique specs and ODC has mastered the playbook for all of them.

So while a new player might be able to lease some land with clay underneath, getting from that to a shelf-ready jug of antibacterial cat litter or a feed additive that meets FDA standards? That’s a decade of R&D, permits, and capex away.

How ODC Stacks Up: Reserves, Production, and Vertical Integration

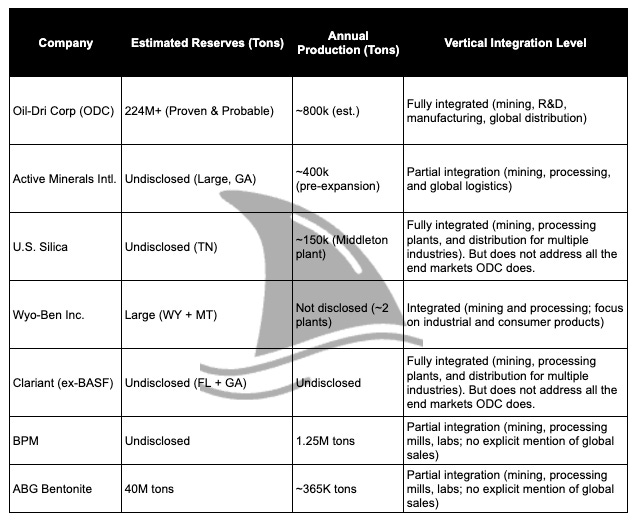

However, ODC has mining competitors, but as you will see, they are smaller, not geographically diversified, nor fully vertically integrated. Below is a snapshot of the clay players in the game today based on their publicly disclosed info, industry reports, and my web research1:

ODC has the most profound integration by far as no one else goes from a mine to a branded pet product.

ODC’s reserve base is not only large but already permitted, adjacent to plants, and diversified across states.

Vertical integration is rare, especially when combined with multi-market product diversity (cat litter, oil refining, feed additives, etc.).

So yes, other players have clay. But none has the setup, the systems, and the spread that ODC has.

Advantage #2. Proximity and Vertical Integration

ODC’s mines are adjacent to or very near its processing plants, creating an efficient mine-to-mill supply chain. They save enormously on transport costs (imagine the difference between hauling heavy clay 5 miles versus 500 miles).

The whole flow from mining and processing to packaging is in-house. This vertical integration means they can ensure quality at each step and are not adding markups along the way. They also have the flexibility to allocate clay to the highest-margin products.

For example, if cat litter demand is booming, they can divert more clay to that line; if an oil purification client needs more tonnage, they adjust accordingly. Competitors who aren’t integrated can’t as easily do that optimization.

Advantage #3. Diverse Product Applications

ODC has a wide breadth of uses for its minerals. This diversification is a competitive strength because it smooths out bumps in any one market. If cat litter sales are soft one quarter, maybe industrial sales or purification sales pick up the slack. It’s hard for a one-trick pony competitor to replicate this. Some small players might only do industrial absorbents, for instance.

ODC’s know-how across many applications and having specialized products (with trademarks like Pure-Flo, Agsorb, etc.) gives it a leg up in various niches. It can also leverage R&D from one area to another (e.g. learning about clay’s adsorptive properties in purification helped them create better animal health products).

Advantage #4. Established Distribution and Relationships

In cat litter, ODC has longstanding shelf space and relationships with major retailers (Walmart alone accounted for 20% of sales). In the industrial sector, they’re a legacy brand in distributors’ catalogues. In purification, they have technical relationships with oil refineries that trust their product.

These relationships and market positions take years to build. A new entrant would face an uphill battle displacing ODC on store shelves or in procurement specs. Additionally, ODC often co-develops solutions with customers (especially in B2B areas), which embeds them further.

Advantage #5. Cost Advantages from Scale

ODC is the market leader in many of its segments (e.g. one of the top cat litter suppliers, top in floor absorbents, major in bleaching clay). This scale means lower unit costs. They operate multiple plants and can produce large volumes, driving down per-unit mining and processing costs. They also purchase inputs like packaging in bulk.

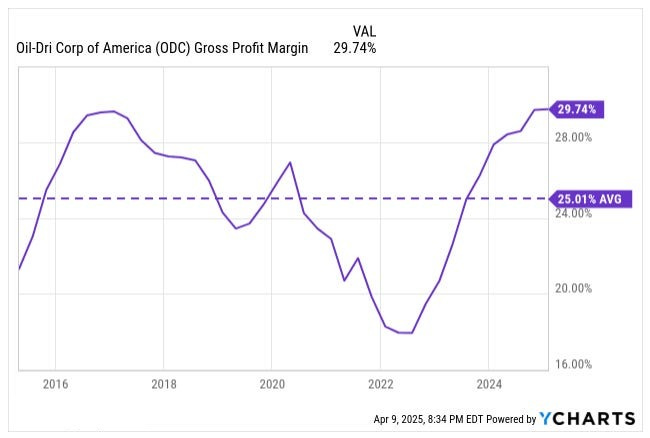

Smaller competitors likely have higher costs per ton and thus either have to charge more (uncompetitive) or accept lower margins. ODC’s gross margin expanded nicely to 29.74% for TTM Q2 FY25, reflecting some of these efficiencies kicking in alongside pricing power and lower gas costs. Moreover, the company’s vertical integration (as mentioned) is inherently a cost-saver.

Advantage #6. Intellectual Property & Experience

While clay itself is a natural commodity, ODC has proprietary processes and decades of intellectual know-how on how to best use it. For example, their R&D refined the lightweight litter process and got an EPA-approved antibacterial litter to market (something competitors hadn’t done).

In animal health, they have patents/trademarks on formulations. This continuous innovation keeps its product lineup relevant and sometimes premium. Their 80-year history also means a wealth of mining and processing experience. They know how to maximize yield from a deposit, how to minimize kiln energy use per ton, etc., which a newcomer would have to learn through costly trial and error.

In sum, ODC has a moat dug out of clay, literally. The combination of owning the resource and controlling the processing gives it a solid defensive wall. This doesn’t mean they have no competition (they do, from big companies like Clorox in branded litter or other clay miners in niche areas), but they have structural advantages.

As an example, a competitor in cat litter might have to buy sodium bentonite from mines in Wyoming and rail ship it to their plant, costing more and subject to mining company price hikes, whereas ODC’s integrated operation in Mississippi/Georgia can mine and process attapulgite clay in one flow. Even if the competitor’s clay is “cheaper” per ton initially, by the time it’s processed and transported, ODC could be equal to or better than in cost.

Financial Performance and Free Cash Flow Profile

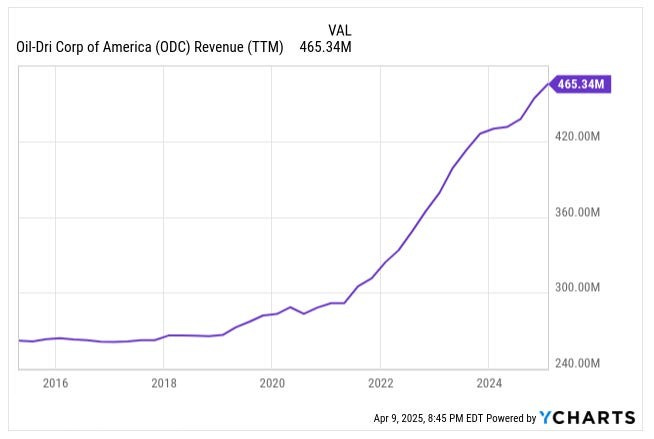

In recent times, the company has been hitting new highs. Fiscal 2024 (year ended July 31, 2024) was a record year on multiple fronts: all-time high revenue, gross profit, and net income.

Revenue

ODC has experienced consistent revenue growth. Revenues were $261 million in 2015 and grew to $437 million by 2014, a CAGR of 5.9%.

By Q2 FY25, revenues were $465 million for the last 12 months.

Specifically for the last quarter (Q2 FY25), ODC pulled in $117 million in net sales, up 11% from the same time last year. The growth came from a healthy mix of 7% organic momentum. Meaning the existing business kept humming along and a 4% lift from the Ultra Pet acquisition, which brought crystal cat litter into the fold.

What pushed revenue higher? A better product mix, some smart price increases, and strong demand for crystal litter, fluids purification products, and animal health solutions.

EBITDA Margin

EBITDA margins have taken a serious turn for the better. Not in a flashy tech-stock kind of way, but in a steady, methodical march upwards.

Let’s unpack what’s driving that margin improvement.

First, the top line has been growing, but more importantly, it’s been growing in the right places. ODC has shifted toward a more profitable product mix with high-margin items like fluids purification, animal health solutions, and now crystal litter (thanks to the Ultra Pet acquisition) making up a bigger slice of the pie. They're specialized, value-added products that command better pricing and contribute more per unit sold.

In Q2 of the fiscal year 2025, gross profit hit $34.4 million, up 11% from last year. That brought gross margins to 29.5%, up slightly from 29.3% the year before, marking the tenth straight quarter of year-over-year gross margin expansion. That kind of streak doesn’t happen by accident.

ODC has been able to raise prices to keep up with inflation without scaring away customers. When raw material, freight, and packaging costs go up (as they did again this quarter, with an 11% increase in domestic cost of goods sold per ton) they’ve managed to pass through a good chunk of that to buyers. That tells you they’ve got a solid moat and a loyal customer base.

SG&A expenses have crept up from $15.8 million last year to $17.0 million this quarter. That 8% bump was mostly a planned investment: higher compensation, marketing spend, and strategic initiatives like building out their data analytics capabilities. Some of it also came from Ultra Pet integration costs and amortizing newly acquired intangibles.

Cash Flow

ODC is a solid cash generator. In FY2024, the net cash provided by operating activities was $60.3 million, up from $49.8 million in 2023. The company had higher earnings and also some working capital release. ODC used this cash in several ways:

$44.3 million for the acquisition of Ultra Pet

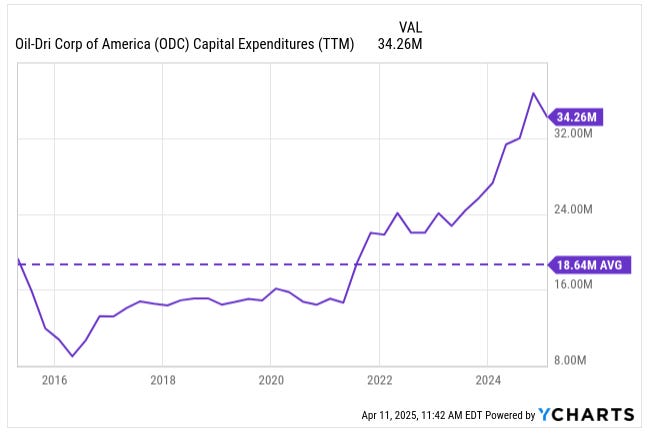

$32 million in capex to expand and improve plants

$7.8 million paid in dividends

$2.8 million repurshasing shares

Even after all that, the balance sheet remained healthy, supported by $23.5 million in cash and a $20 million debt issuance, bringing total debt to $70.7 million (including capital leases).

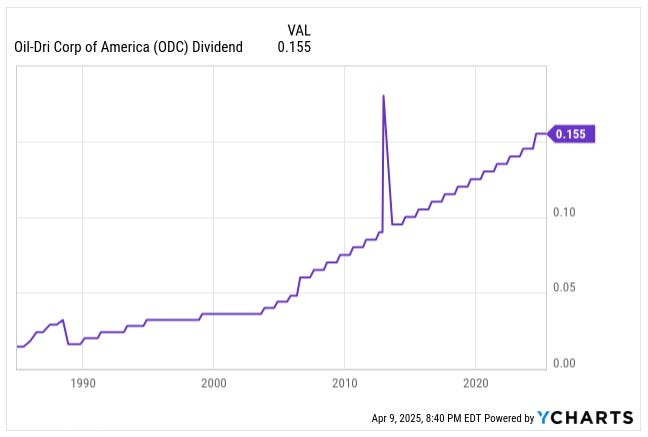

On a free cash flow (FCF) basis (operating cash minus capex), ODC generated roughly $28 million in FCF in 2024. This FCF profile (steady and positive) has enabled those annual dividend hikes and opportunistic share repurchases.

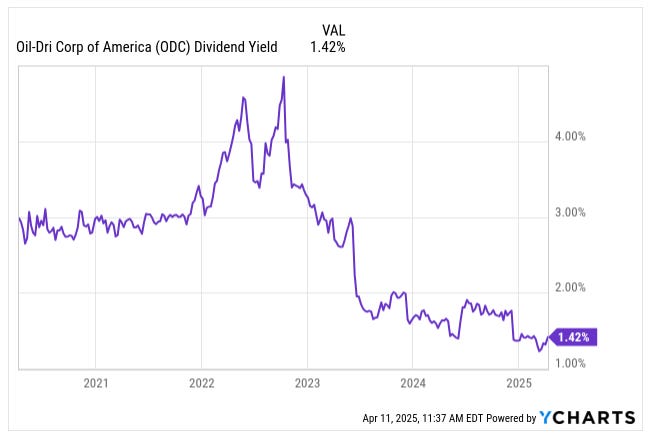

ODC has paid dividends since 1974 and has increased them for 21 consecutive years. Currently, the quarterly dividend is $0.31 for common stock (and $0.233 for Class B stock) after the latest 7% hike in 2024. Yes, the Class B shares get a smaller dividend (more on that quirky capital structure next). This track record of rising dividends, usually by a penny or two each year, underscores consistent cash generation.

ODC’s dividend yield used to be a nice 3%, but with the current share price appreciation, it contracted to 1.4%. It isn’t huge, but it’s a nice bonus on top of stock appreciation.

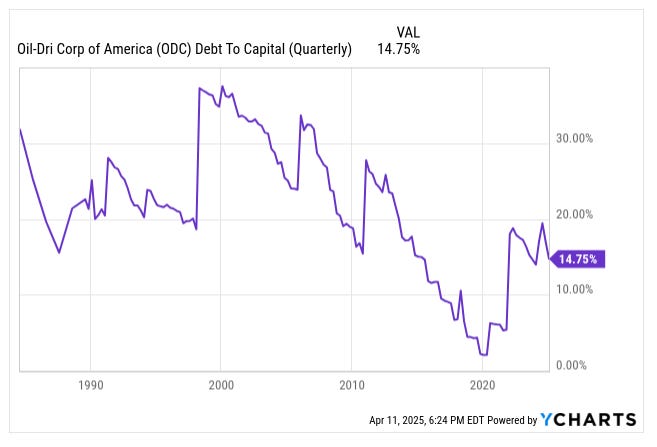

ODC’s balance sheet has historically been conservatively managed. They do use some debt (they have a revolving credit facility), but the leverage is modest. The Ultra Pet acquisition was done for $46 million in cash, funded by a combination of cash on hand and a $20 million draw on their credit line.

Even after that, the company’s debt levels remain quite reasonable relative to EBITDA, standing at a net debt to EBITDA of 0.4x TTM. This conservative approach is partly due to the family control – the Jaffees have tended to avoid risky debt-fueled moves, preferring steady growth.

One thing to watch financially is that ODC’s capex has increased. They are investing in capacity expansion (perhaps adding production lines, efficiency improvements, or environmental upgrades). While this eats up some cash in the short term, it likely supports future growth (for example, expanding a plant to produce more lightweight litter). In its 10k filing, ODC indicated it is supporting increased demand through these capex projects.

ODC has always been a solid, cash-generating business. But over the past few years, it’s quietly levelled up. ROE and ROIC have both seen a meaningful step change, driven not by some flash-in-the-pan cost-cutting but by a structural shift in the product mix.

The company has been intentionally moving away from lower-margin bulk commodities and toward more value-added, higher-margin products like crystal litter, natural animal health additives, and performance-grade purification materials. These segments don’t just boost margins; they also demand fewer capital-intensive expansions, which translates to stronger returns on the capital already in place.

This shift is paying off. In the fiscal year 2024, ODC delivered $39.4 million in net income, up from $29.6 million in 2023. But what jumps out is EPS. For years, diluted EPS floated below the $1.00 mark (solid but uninspiring). That changed in a big way.

In the fiscal year 2024, diluted EPS hit $2.72, and based on trailing twelve-month performance, the company is now running at $3.13 per share.

There’s no trickery here. The earnings improvement stems from margin expansion, product mix upgrades, and a long-runway strategy that’s actually working. You can feel it in the numbers, and you can see it in the business model: more recurring, less cyclical. Less dirt, more design. If this trajectory holds, the old valuation multiples simply won’t do justice to what this business is becoming.

Dual-Class Shares and Family Control: The Jaffee Legacy

One cannot talk about ODC without mentioning its unique capital structure and governance. ODC has two classes of stock: Common Stock (NYSE: ODC) and Class B Stock. The key difference is in voting power. Each share of Common Stock gets 1 vote, while each share of Class B gets 10 votes. Class B is essentially a super-voting stock.

Importantly, Class B can be converted to common on a 1-for-1 basis at any time by the holder, but if it’s sold or transferred to anyone outside the family, it typically must convert to common (to prevent high-vote shares from getting into outsiders’ hands). As of February 28, 2025, there were about 10.3 million Common shares and 4.3 million Class B shares outstanding.

The Jaffee family, descended from founder Nick Jaffee, owns those Class B shares. Specifically, Daniel S. Jaffee, the current CEO (and grandson of the founder), along with a family partnership, controls over 50% of the total voting power of ODC.

The company qualifies as a “controlled company” under NYSE rules because of this concentration of votes. Dan Jaffee has been CEO since the mid-1990s and Chairman since 2018, and with the family’s Class B stake, he effectively can elect the board and steer the company’s direction. The family partnership (the Jaffee Investment Partnership, L.P.) divvies up votes among Dan and his siblings, but Dan holds the largest portion of those votes as general partner.

For investors, the dual-class structure means that public shareholders have diluted voting influence. Even if an outside investor bought a large chunk of the Common Stock, they’d have minimal say if the Jaffees continue to hold Class B.

For instance, as of the record date in 2024, Dan Jaffee and his partnership had more than 50% voting power but far less than 50% of the economic ownership. This setup can ward off hostile takeovers (since you can’t easily buy control). It also means the company can take a longer-term view, as the controlling family isn’t at risk of being ousted by activist shareholders easily.

The downside is that traditional corporate governance checks are weaker. If the controlling family’s interests ever diverged from those of public shareholders, the latter don’t have much recourse. However, in ODC’s case, the family’s economic interests are still significant as they have $184 million of equity in the company, so they are incentivized to increase shareholder value.

One interesting aspect is that Class B shares get a lower dividend per share than Common. By charter, Class B’s dividend cannot exceed 75% of the Common dividend. Indeed, in 2024, Common got $0.31 quarterly while Class B got ~$0.233 quarterly (exactly 75%).

Why would the family accept less cash per share?

Because the trade-off is control. It’s a system set up long ago to ensure public investors get a little extra reward in exchange for giving up voting power. Also, it subtly encourages Class B holders to convert to Common if they no longer value control or to prevent an insider from unfairly enriching themselves with the high-vote stock. In practice, the Jaffees have kept their Class B largely intact, content with the lower dividend as a price for maintaining control.

Daniel Jaffee’s control has been viewed as a stabilizing factor. The company has been run relatively conservatively and has stuck to its knitting, likely avoiding fads or shortsighted moves that outside pressure might have induced. It’s a classic family business vibe: they think in decades, not quarters.

For example, continuing to invest in maintaining 40-year clay reserves or raising the dividend by just a penny consistently reflects long-term stewardship. The board does have independent directors, but the family’s influence looms large. The NYSE grants “controlled companies” exemptions from some governance requirements (like needing a majority independent board), though ODC actually does have a majority of independents on its board currently.

For an investor, the dual-class structure means you’re betting on the Jaffee family as much as on the business. So far, that’s been a favourable bet as the stock has compounded nicely over the years, and dividends kept flowing. Just be aware that any change in control (e.g. if the family ever decided to sell the company or their stake) would be entirely up to them to initiate.

Dan Jaffee is in his early 60s, and presumably, the next generation will eventually take the reins, or the family could consider a sale if there’s no succession interest. But Class B ensures they won’t be forced into anything.

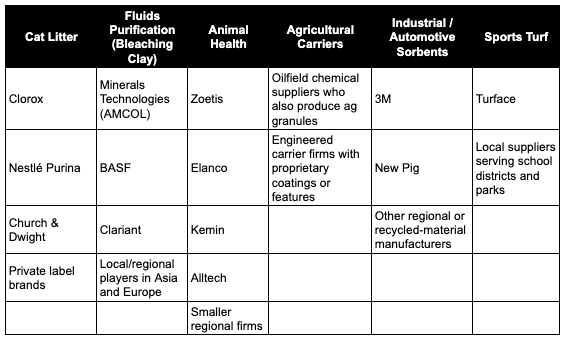

Oil-Dri’s Competitive Landscape: A Dirt-By-Dirt Breakdown

The competition varies depending on which part of its business you zoom in on. Some rivals have deeper pockets. Others are nimble startups chipping at niche markets. But across the board, ODC tends to punch above its weight, thanks to its vertical integration and decades of product knowledge. Below, I tried to collect the major competitors. I may have missed some, but I think those are the main ones.

Cat Litter is a crowded and cutthroat space, dominated by multi-billion-dollar consumer goods companies that can outspend anyone on advertising. ODC plays in this arena both under its own brands and as a private label manufacturer, including a long-term deal to supply Clorox’s Fresh Step coarse litter (remember this as we will discuss Clorox in detail).

The biggest challenge here is marketing muscle.

ODC doesn’t have the same TV commercial budgets. The advertising budgets for Clorox (CLX 0.00%↑) ($832 million in 2024) and Nestlé (pink: NSRGY)($8.1 billion in 2024) are multiples of ODC’s.

Even if ODC’s entire SG&A is advertising (which is not, as the majority of SG&A is salaries and distribution), Clorox’s advertising budget and Nestlé’s would be 12x and 114x that of ODC. But ODC offsets that with innovation (like lightweight and antibacterial litters) and operational efficiency from owning its own clay.

Thanks to the Ultra Pet acquisition, ODC has also stepped into the crystal litter space, which is mostly dominated by imported brands until now. This opens a new front of competition with brands like PrettyLitter, which markets heavily online.

The fluids purification segment is less consumer-facing and more industrial and globally competitive. The big differentiator here is performance and technical support. Companies don’t want surprises in food or fuel production. So, ODC wins by being reliable and by constantly improving its formulations (think lower impurities, better filtration, more precise targeting of contaminants).

The animal health market is crowded, but the real fight is over efficacy and regulatory trust. A product like Calibrin-Z that binds mycotoxins needs clinical proof. ODC’s strategy is to carve out space with natural, clay-based alternatives to antibiotics, appealing to producers looking to keep animals healthy without heavy meds.

That’s where the contrast with big names like Zoetis (ZTS 0.00%↑) and Elanco (ELAN 0.00%↑) comes in. These two are animal pharma giants. They sell vaccines, antibiotics, and hormonal treatments that require regulatory approval and, in many cases, veterinarian oversight.

Their products are potent and highly effective, but they also come with increasing scrutiny as the industry shifts away from routine antibiotic use. ODC isn’t trying to play in that sandbox. Instead, it's positioning itself as a complementary solution (or in some cases, a substitute) for producers who want to boost gut health, reduce toxin load, and improve feed efficiency without triggering red flags from regulators or consumers.

While Zoetis and Elanco are the Pfizer and Merck of the barnyard, ODC is more like the natural supplement aisle backed by science but built for a different kind of livestock wellness strategy.

In the industrial/automotive segment, ODC is a big fish. ODC got legacy relationships, low costs, and brand recognition. Plus, they’re everywhere: industrial catalogues, car shops, even big box stores.

Finally, I should mention that two board members were employees of the competition. Namely, Lawrence Washow at Minerals Technologies and George Roeth at Clorox. While I see having industry experts on the board as a benefit, we need to double-click on Clorox, as it is a supplier and a client as well. That is the next section.

The Clorox Conundrum: Partner, Competitor… Boardroom Connection?

Now, here’s a subplot worthy of a Netflix docuseries: ODC and The Clorox Company have a relationship that’s part symbiotic, part competitive, and part family dinner.

Customer and Co-Manufacturing Partner

Clorox doesn’t just make bleach. It owns Fresh Step and Scoop Away, two of the biggest cat litter brands in the U.S. Clorox doesn’t manufacture all of its litter. Instead, it outsources the production of its Fresh Step coarse litter to ODC. Under a long-term agreement, ODC handles the manufacturing, while Clorox controls the marketing, branding, and sales strategy.

So in this case, Clorox is a client. ODC is the behind-the-scenes producer making the product that ends up in millions of homes under the Fresh Step name.

Competitor

At the same time, Clorox is a major competitor in the scoopable litter space, especially with its Scoop Away brand. These go head-to-head with ODC’s own Cat’s Pride and Jonny Cat litters on store shelves. Both companies market aggressively, but Clorox has more ad firepower. ODC competes on innovation and private label flexibility.

Boardroom Link

Here’s where it gets more intriguing: George Roeth, Lead Director of ODC’s board, spent nearly three decades at Clorox, including serving as Chief Operating Officer for its Lifestyle, Household and Global divisions. He also chaired the board of the Clorox-P&G joint venture for Glad products.

Why does this matter?

Having someone who knows Clorox inside and out on ODC’s board could give them a leg up in managing that delicate relationship. Roeth understands how Clorox operates, what drives its decisions, and how to maintain a partnership that could easily get tense.

It’s not every day that your board includes someone who used to run parts of your largest competitor and customer. The companies have maintained a multi-year partnership without public friction. ODC’s contract with Clorox gives it consistent volume and utilization in its plants, helping balance the lumpy retail business.

In short, Clorox and ODC are like co-parents at a PTA meeting: sometimes competitive, sometimes cooperative, but both deeply tied to the same sandbox. And thanks to a shared history and boardroom crossover, they seem to be managing the relationship better than most. That, in corporate America, is no small feat.

Valuation

I estimate the intrinsic value of ODC’s shares at $64, based on a DCF model. The cost of capital I used was 8.1%, which reflects an unlevered beta of 0.82 (corrected for cash), an additional 100 basis points premium for the control dynamics tied to the Jaffee family, and an optimal debt-to-capital ratio of 40%—not too hot, not too cold.

But here’s the thing: ODC doesn’t operate with an “optimal” balance sheet—it operates with a family business mindset.

Daniel Jaffee, like many second- or third-generation business leaders, is allergic to debt. The company occasionally lets leverage drift into the mid-30s, but as soon as earnings improve or capex slows, they quickly pull it back down.

The story of my uncle and debt

This kind of financial conservatism reminds me of my uncle. He runs a successful business and swears by one principle: no debt, no headaches. I once tried to explain that borrowing smartly could help him grow faster. Even after interest, he’d make more money. He smiled, nodded, and then proudly told me he hasn’t owed a dime to a bank in 30 years. Game over.

ODC is cut from the same cloth.

Still, if the company were ever to lean a little more into leverage, there’s room to unlock value. With a modest bump in debt, ODC could acquire smaller competitors (especially in niche areas like crystal litter or ag products), expand capacity in high-margin segments like purification or animal health, boost the dividend, or repurchase more stock.

Share repurchases could offer a clever mechanism for the Jaffee family to convert Class B shares to Common, allowing them to receive a higher dividend while maintaining control. It’s a tidy little play that’s rarely discussed.

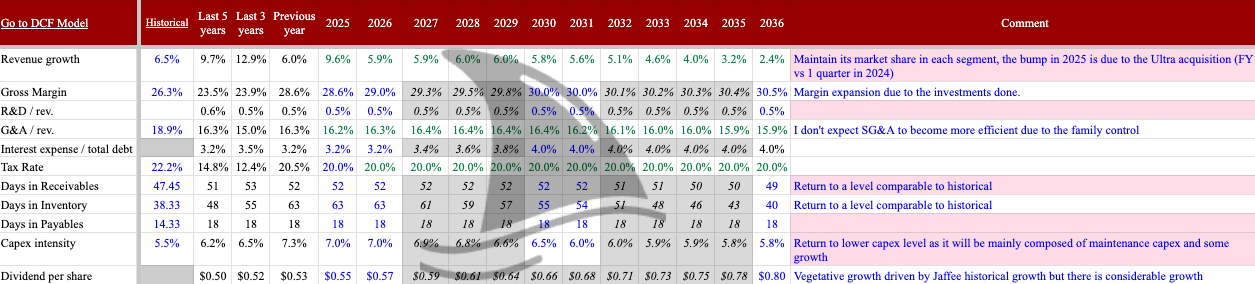

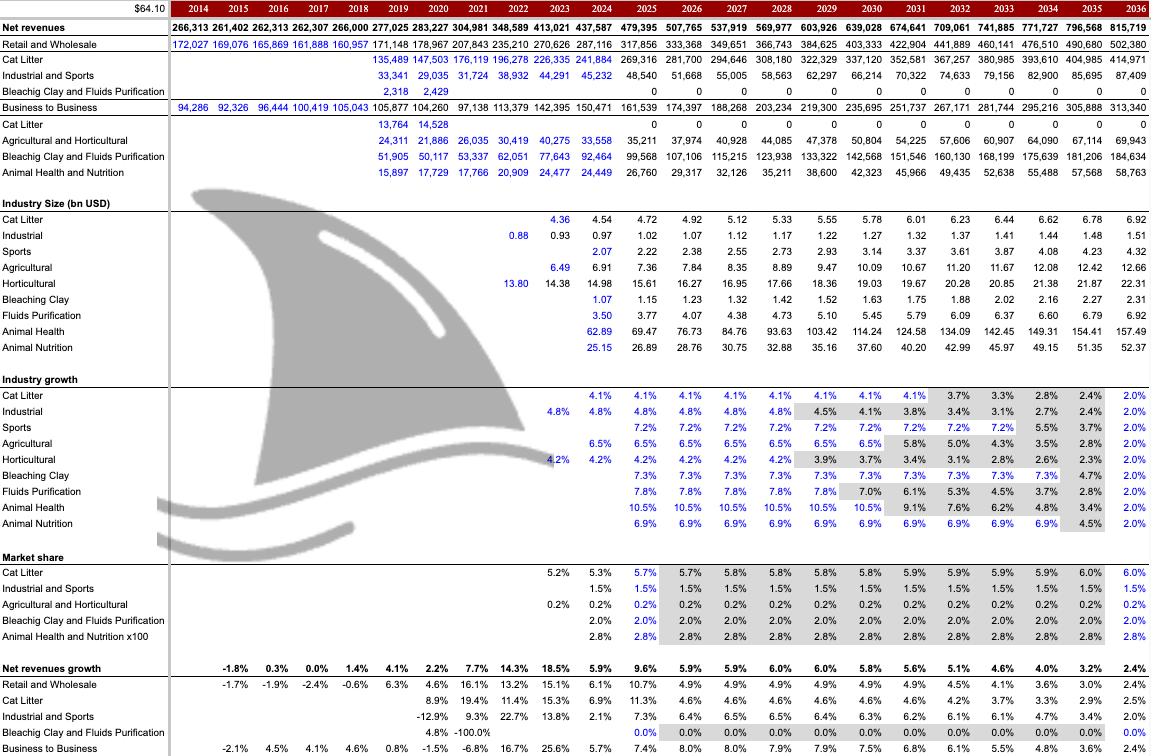

Below are the key assumptions baked into the DFC model.

And below is a double-click on the top line.

The DCF model is grounded in conservative assumptions. The U.S. cat litter market was worth $4.36 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at around 4.1% annually through 2030. I assumed that ODC’s market share would rise modestly from 5.3% to 5.7%, reflecting the integration of Ultra Pet and an increased presence in the crystal litter segment. Over time, I expect market share to reach around 6.0%, as the company improves its product offerings and potentially acquires smaller regional players.

The shift toward domestically sourced inputs also gives ODC a structural advantage, particularly if tariffs on foreign clays or finished litter products persist. With vertically integrated operations and long-term access to high-quality clay, the company is positioned to capture market share from import-reliant competitors.

For the non-retail segments, I assumed flat market share, even though there’s room for upside. The assumptions around margin reflect a similar conservatism. I kept B2B margins in line with historical levels and held corporate expenses steady. For the Retail and Wholesale segment, I modelled slight margin expansion as top-line growth dilutes fixed costs and recent process improvements begin to bear fruit.

The overarching idea is that this is a quiet compounder. One with optionality hidden in its capital structure and real pricing power embedded in its mine-to-shelf control. At a $64 intrinsic value, you’re not paying up for blue-sky assumptions. You’re simply valuing a stable, underappreciated business based on what it already does well and giving a little credit for what it could do better if it ever chooses to lean in.

From Tariffs to Walmart: Four Risks That Matter

The “Liberation Day” Tariffs and Trade Winds

An interesting external factor for ODC has been international trade policy. Specifically, the tariffs introduced during the Trump administration’s trade war with China. In 2018-2019, President Trump imposed waves of tariffs on Chinese imports (10%, then 25% on a broad range of goods), and China retaliated in kind. More recently, in 2025, Trump (campaigning on what he dubbed “Liberation Day” tariffs) talked about even more sweeping duties. Essentially a reciprocal tariff on all countries that have tariffs on U.S. goods (“Liberation Day” Tariffs Explained).

Trump’s global policies are as volatile as his X account. I started this deep dive two days after the reciprocal tariffs were announced, and by the time I reached this part of the deep dive (yes, it takes me a couple of days), Trump halted the tariffs for 90 days while the countries negotiate.

While the politics are complex, the question for ODC is: How do tariffs affect a company that mostly sells dirt?

There are a few angles to consider:

Higher Costs on Imported Inputs: ODC does import some materials or finished goods. One notable area is the polypropylene sorbent products (pads, booms). If those or their raw materials are sourced from China or overseas, a tariff would raise their cost. Similarly, packaging materials (certain plastics or woven bags) from abroad could get pricier. During the 2018 tariff rounds, many industrial companies saw cost upticks on things like plastic resin and machinery. ODC likely had to pay more for certain packaging or equipment due to those tariffs (though they haven’t disclosed a specific hit, it was part of the general inflationary pressures of that period).

Levelling the Playing Field vs. Foreign Competitors: Tariffs can also help ODC by making competing imported products more expensive in the U.S. market. A great example is silica gel cat litter. Before ODC bought Ultra Pet, the U.S. market for crystal litter was largely supplied by imports (often from China). Tariffs on Chinese goods would increase the cost of those imported litters. If a $10 bag of Chinese-made crystal litter faced a 125% duty, it might end up $22.50 at retail, making ODC’s domestically produced litter considerably more attractive. ODC’s traditional clay litters never really faced import competition (clay litter is heavy and not worth shipping overseas), but in newer segments like silica litter, it could gain an edge. Also, if any competitors import clay from abroad, tariffs would hurt those competitors more than ODC (which mines domestically). While the large reciprocal tariffs are on hold for 90 days, there is a blanket 10% tariff in place and a 125% on China. Thus, ODC’s U.S.-centric production could become a big advantage, as virtually all imported pet products, chemicals, etc. would cost more relative to ODC’s American-made goods.

Retaliatory Tariffs on Exports: The flip side is when other countries retaliate. China, for example, could impose tariffs on U.S. exports. ODC does export some products (like animal feed additives or bleaching clay) to China and elsewhere. During the trade war, China targeted many agricultural and chemical goods. It’s plausible that certain ODC products got caught in those tariffs, contributing to lower sales in Asia in 2019-2020. Even now, trade tensions can affect ODC’s foreign operations — for instance, if a country subsidizes local producers or puts import duties, ODC might lose some market share in that region.

Overall, ODC managed through the 2018-2019 tariff turbulence without major issues, as evidenced by its continued growth. The company likely passed through minor cost increases and benefited in areas where competition thinned. For ODC, a broad tariff environment in the U.S. market tends to protect it (due to its domestic manufacturing), while any foreign retaliatory measures pose a manageable headwind, given that a majority of its sales are within North America.

As a note of scale, ODC is not heavily dependent on China or any single foreign country. In the fiscal year 2024, less than 5% of its net sales came from China (the company even reorganized its China business to sell via a distributor). So tariffs, while not trivial, are not make-or-break for ODC. One could argue that ODC has benefited from the reshoring trend that tariffs encourage. U.S. manufacturing and agriculture staying onshore means local demand for absorbents, carriers, etc., remains strong.

Customer Concentration: Walmart Risk

Walmart accounts for roughly 20% of ODC’s net sales. That’s a big chunk of revenue tied to a single buyer. If Walmart were to switch suppliers, reduce shelf space, or push back harder on pricing (as they’re known to do), it could hit ODC’s top line fast.

This isn’t theoretical. Walmart is famous for squeezing vendors and rotating private label partners (I’ve seen it first-hand during my days at Kraft Heinz). While ODC has diversified across product types and channels, this level of customer concentration still adds vulnerability.

The company has some leverage thanks to long-standing relationships and its ability to private-label and co-manufacture, but the balance of power in retail always favours the big box.

Energy Costs: Natural Gas Volatility

A key input in Oil-Dri’s production process is natural gas, which is used to dry and heat-treat the clay in its kilns. The company doesn’t just sprinkle this stuff into a bag; it has to superheat it first, and that takes serious energy.

In some plants, natural gas can make up 25–30% of production costs. While ODC hedges a portion of its gas exposure using forward contracts, it’s still vulnerable to swings in energy markets. A sharp spike in gas prices, like the one we saw during the 2022 energy crunch, could compress margins, especially if pricing power weakens or costs rise faster than the company can pass them through.

And because natural gas is also tied to geopolitical events and weather volatility, this isn’t a small or rare risk. The hedging strategy softens the blow, but it doesn’t eliminate it.

Regulatory Risk: Unpatented Mining Claims in California

A portion of ODC’s clay reserves in California (3.5% of the proven reserve and 8.5% of the probable reserves) sits on unpatented federal land leased from the Bureau of Land Management. While these leases give the company the right to mine, they come with regulatory uncertainty. Any future changes to federal mining laws, such as the introduction of royalty fees, increased maintenance costs, or changes to the patent system, could make mining on these claims less economical or even impractical.

The company already notes that operating and expanding processing facilities on these sites requires multiple layers of government approval, which could delay or restrict growth. In a worst-case scenario, if fees are imposed or access is restricted, ODC may face higher costs or lose access to key raw material sources, adding supply risk to its vertically integrated model.

Conclusion: Dirty Business, Clean Profits

ODC Corporation of America proves that even the most unassuming businesses, like digging up clay and selling cat litter, can have surprising depth and durability. By mastering the science of sorbent minerals and diversifying into every niche imaginable (pets, farms, kitchens, factories, and even baseball diamonds), ODC has built a resilient enterprise that turns dirt into dollars.

Its vertical integration from owned mines to packaged products gives it enviable control over costs and quality, forming a moat that has kept the company thriving for decades. Family leadership and a dual-class share structure have kept the company on a steady long-term course, prioritizing gradual growth and shareholder returns over hype.

Investors in ODC get a slice of a steady, cash-generative business that has weathered wars (literal and trade), inflation, and shifting consumer habits, all while quietly growing in value. The next time you pour out some cat litter or see a mechanic toss absorbent on an oil spill, you might think of ODC. It’s a reminder that sometimes the best investment stories are hiding in plain sight (or under our very feet).

The sources for the table are as follows:

ODC: 2024 10k filing

Active Minerals International: https://activeminerals.com/about-us/#:~:text=logistics%20know%2Dhow

U.S. Silica: https://www.ussilica.com/locations/middleton-tn, https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/u/NYSE_SLCA_2021.pdf#:~:text=four%20million%20ton%20per%20year,

https://www.ussilica.com/

Wyo-Ben:

https://www.wyoben.com/#:~:text=three%20plant%20facilities,

https://www.wyoben.com/#:~:text=Wyo%2DBen%20mines%20from%20its%20reserves%20in%20the%20Big%20Horn%20Basin%20region%20of%20Wyoming%20and%20processes%20a%20multitude%20of%20products%20from%20its%20three%20plant%20facilities%20which%20serve%20a%20global%20marketplace.

Clariant: https://www.clariant.com/en/Investors/Results-Reports-and-Publications/Capital-Markets-Day

ABG Bentonite: https://www.echemi.com/shop-us20180832100037877/index.html#:~:text=40%20million%20tonnes