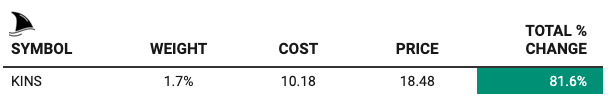

Kingstone Companies (KINS): Hold or Fold After the +80% Surge?

A deep dive into Kingstone Companies: this stock analysis shows how a disciplined turnaround drove the insurer from crisis to 80 % gains—and why the stock still points to 20-30 % upside.

Updates:

Nov14’25: Q3 2025 Earnings Results & revised target price ($23 → $25)

Aug20’25: Q2 2025 Earnings results

May11’25: Q1 2025 Earnings Results

Welcome back to the best investment newsletters 😉. In this deep dive, a Simpsons gag got me thinking about insurance. When I saw The Simpsons episode where Moe sticks a crayon up Homer’s nose to dumbify him again, Moe was not satisfied until Homer yelled, “Extended warranty? How can I lose?” I laughed, but also found myself curious—why exactly was this funny?

After a bit of reflection, it became clear: the humour stems from the absurdity of feeling smart while statistically being on the losing side of the bet. Extended warranties, like many poorly structured insurance policies, typically favour sellers rather than buyers. Ironically, despite always avoiding extended warranties myself, my MacBook Pro crashed at 14 months, and my washer needed a replacement part exactly one month after the warranty expired. 🤔

Yet, following the timeless adage, "If you can't beat them, join them," I began exploring investments in the insurance sector. After all, the greatest wealth-building machine for Warren Buffett has been insurance. Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway has famously grown wealthy by collecting insurance premiums upfront, profiting from disciplined underwriting, and smartly investing the "float"—the premiums collected before claims are paid out.

That’s when I first bought Kingstone Companies ( KINS 0.00%↑ ) stock at ~$10—a contrarian deep-dive pick premised on a New York insurer’s turnaround. Initially, my thesis recognized that new leadership and a focused strategy could breathe life into this micro-cap property & casualty insurer, despite the stock having already surged significantly from its lows. Fast forward to today, Kingstone’s stock has climbed above $18.

Under CEO Meryl Golden’s leadership, Kingstone didn’t just recover — it staged a remarkable turnaround. After refocusing on core markets, tightening underwriting standards, optimizing reinsurance, and aggressively cutting costs, KINS returned to strong profitability, improving its combined ratio from over 100% to ~80% by 2024. Recent market exits by competitors have further boosted Kingstone's premium growth and market position.

Having entered around $10, shares now trade above $18, reflecting much of this transformation. While substantial gains have already been made, continued earnings growth and disciplined execution offer a potential 20–30% further upside. However, the valuation no longer presents a deep discount, making Kingstone a "Hold" rather than a clear "Buy," and potentially a candidate for trimming if better opportunities arise.

Subscribe to the best investment newsletter for exclusive deep-dive stock investing ideas → just $130/yr

One timely idea like KINS (+80%) can more than pay for your subscription.

That is the brief thesis. But if you want more (I know you do 😉) stick around for the deep dive. I'll revisit Kingstone’s story from its modest beginnings to its recent revival, evaluate the competitive landscape and unique dynamics of the New York insurance market, and ultimately assess whether Kingstone deserves to remain in the portfolio. While I acknowledge the "easy" gains have been captured, I'm inclined to remain invested, not just for the 20-30% upside, but because the new management has done a great job so far, potentially setting the stage for positive surprises.

Table of Contents:

Deep Dive Company Overview: How Kingstone Became a Niche P&C Insurer

KINS traces its roots all the way back to 1886, starting as a small insurance agency in Kingston, NY. For over a century, it operated in the traditional agency model — selling policies but not underwriting them. That changed on July 1, 2009, when Kingstone completed the acquisition of 100% of the outstanding common stock of Commercial Mutual Insurance Company (CMIC), a long-established insurer that was undergoing a structural transformation. As part of the deal, CMIC converted from an advanced premium cooperative to a stock property and casualty insurance company and was rebranded as Kingstone Insurance Company (KICO). Kingstone’s evolution into a full-fledged underwriting carrier, with direct control over pricing and risk, marked a defining moment in its history.

Today, KICO writes property and casualty insurance in New York through a network of independent agents and brokers. It’s a small, sharp operator with deep local roots. Kingstone’s bread-and-butter products are personal lines insurance – homeowners, renters, dwelling fire, and personal umbrella policies – primarily in downstate New York (Long Island and the NYC area). The company also offers some commercial auto coverage and has licenses in neighbouring states, but as we’ll see, it recently refocused almost exclusively on its home turf.

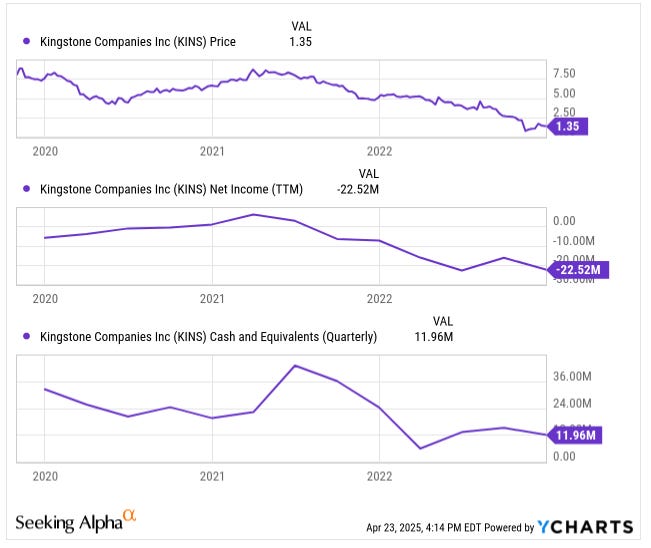

Despite its long history, KINS remained a very small player in the insurance world. As of 2024, KICO is the 12th largest writer of homeowners insurance in New York State. The company’s size and regional focus mean it competes with both local insurers and giant national carriers in its niche. For much of the 2010s, Kingstone enjoyed modest success growing its premium base, but it hit a rough patch in the late 2010s and early 2020s. Combined ratios — a key metric I’ll explain shortly — climbed, underwriting losses piled up, and the firm even had to halt dividends and raise cash to stay afloat. By late 2022, the situation was dire enough that the long-time CEO (Barry Goldstein) stepped down, and a new chief executive, Meryl Golden, was brought in mid-2023 to right the ship. Investors were justifiably skeptical at that point; Kingstone’s stock had plummeted to the low single digits amid mounting losses and dwindling cash.

However, Kingstone’s story took a sharp turn for the better once Golden took the helm. Since the start of 2023, the share price has multiplied by 12 times as the company executed an impressive turnaround.

The once-struggling insurer started posting profits again, and sentiment flipped from despair to optimism. What exactly changed? To answer that, we need to understand some insurance basics and then dive into the “Kingstone 3.0” strategy that Golden implemented.

Insurance Industry Basics: How Insurers Make Money (and What Makes a Good One)

P&C Insurance 101

KINS operates in the property and casualty (P&C) insurance space. In plain English, that means they sell protection against losses to property (like homes, cars, personal belongings) and against liability (if someone is held responsible for causing damage or injury). The business model of a P&C insurer has a few moving parts, but it’s not too hard to grasp. An insurer collects premiums upfront from customers in exchange for the promise to pay future claims if and when accidents happen. In the meantime, the insurer can invest those premium dollars (often in bonds or other conservative investments) — this is often called the “float.” The goal is twofold: (1) earn an underwriting profit by paying out less in claims and expenses than you took in premiums, and (2) earn investment income on the float. A great insurer will do both consistently; a merely decent insurer might at least break even on underwriting and rely on investments to make a profit.

The Combined Ratio — A Vital Sign

One of the most important metrics for an insurer’s health is the combined ratio. This ratio is essentially expenses plus losses divided by premiums. It’s analogous to a gross cost ratio or inverse profit margin, where under 100% is a win (underwriting profit) and over 100% is a loss. The combined ratio is usually broken into two components: the loss ratio (the percentage of premium spent paying claims and claim adjustment costs) and the expense ratio (the percentage spent on operating expenses like underwriting, marketing, commissions, etc.).

For example, if an insurer has a 60% loss ratio and a 30% expense ratio, its combined ratio is 90%, meaning it spends $0.90 for every $1.00 of premium, leaving a $0.10 profit from underwriting operations. On the other hand, a 105% combined ratio means the insurer is paying out $1.05 for every $1 earned – not a sustainable situation long-term (though short-term losses can sometimes be offset by investment gains).

What makes an insurer “good” in this context is consistently keeping that combined ratio below 100. This can be achieved by careful underwriting (selecting and pricing risks properly so that claims costs are controlled) and expense discipline (running a lean operation). A strong insurer will also maintain adequate reserves — the money set aside for claims that have occurred but not yet been paid. If reserves are too low, an insurer might get a nasty surprise of additional losses later (known as adverse development); if reserves are conservative, the company can occasionally release excess reserves, which boosts earnings.

Another hallmark of a good insurer is smart use of reinsurance. Reinsurance is basically insurance for insurance companies: KINS (like most insurers) buys policies from larger reinsurers to cover extreme losses, especially catastrophes. By ceding a portion of premiums to reinsurers, Kingstone can limit its exposure to, say, a massive hurricane, akin to sharing the risk (and reward) with a partner. Reinsurance isn’t cheap, but it’s crucial for a small company to survive big disasters. Kingstone’s reinsurance program, for instance, covers 100% of catastrophe losses above a $4.25 million retention per event (with coverage up to $275 million beyond that). In other words, Kingstone is on the hook for the first few million of a disaster, but anything above that is passed to reinsurers (after paying a premium for that protection).

What Went Wrong Before

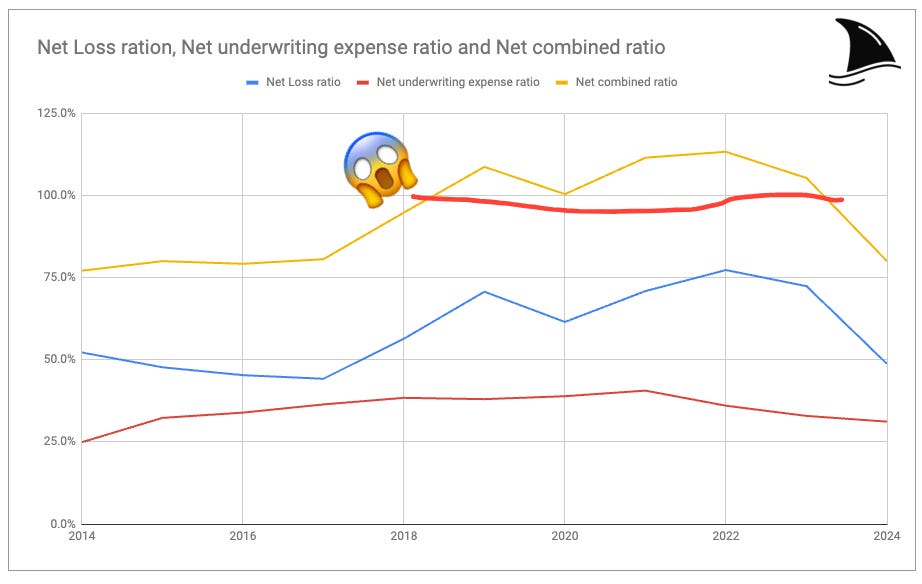

In Kingstone’s case, the late 2010s saw a deterioration in these key metrics. Both the loss ratio and expense ratio were trending the wrong way after 2017 and were over 100 from 2019 to 2023. This led to underwriting losses.

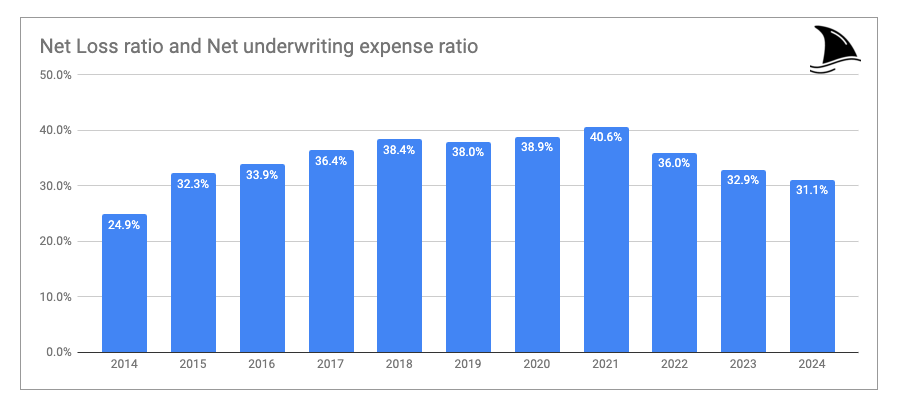

The company expanded into some other Northeastern states outside New York and wrote more types of policies, but many of these moves backfired. Losses mounted (partly from underwriting missteps and partly from some bad luck with catastrophic weather events), and the expense base was too bloated for the size of the business. By 2021, Kingstone’s net expense ratio had blown out to around 41%, well above industry norms.

Essentially, Kingstone was paying out more in claims and costs than it earned in premiums – an unsustainable situation that eroded its capital. To plug holes, management even issued new shares (diluting shareholders) and suspended dividends to conserve cash. It was clear that changes were needed for Kingstone to survive.

Turnaround Stock Analysis: Inside “Kingstone 3.0”

In mid-2023, Meryl Golden stepped in as the new CEO with a mandate to fix the ship. She and her team rolled out what they dubbed “Kingstone 3.0,” a comprehensive turnaround strategy aimed at restoring profitability. The changes under Kingstone 3.0 addressed the company’s problems from multiple angles:

Refocus on Core Markets

KINS drastically pulled back from its unprofitable business outside New York. States like New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island had contributed disproportionately to losses. By working with regulators, KINS shrank its non-core portfolio from roughly 20% of premiums to just about 5%. Now, the vast majority of business comes from downstate New York, a market the company knows well. This refocus meant dropping a lot of problematic policies and concentrating on areas where KINS has historical data and agent relationships.

Better Pricing and Underwriting (Select Product)

To get ahead of inflation and rising loss costs, KINS implemented pricing adjustments and tighter underwriting standards. A key initiative was the rollout of a new homeowners policy form called “Select.” Think of Select as a smarter, more disciplined version of their insurance product — it targets lower-risk properties and charges rates that more accurately reflect the risk (including factoring in reinsurance costs). The result has been fewer claims on this book of business. By late 2024, the Select product accounted for 34% of Kingstone’s policies, and it was experiencing about 20% fewer claims than the older legacy policies.

For example, in personal lines, the claim frequency on Select was around 1.6% versus 2.2% for legacy policies. This indicates that the company’s shift to more stringent underwriting is paying off in lower loss frequency. Kingstone also pushed through rate increases where needed – e.g. a 5% hike on Select homeowners and 10% on dwelling fire policies in late 2024 – to ensure premiums kept up with inflation.

Reinsurance Optimization

The team took a hard look at reinsurance usage and costs. Kingstone now prices its policies with a clear eye on reinsurance expenses – essentially baking the cost of catastrophe protection into the premiums it charges. By aligning underwriting with reinsurance strategy, they aim to avoid surprises where a policy is underpriced relative to how much it costs to reinsure that risk. They also added targeted reinsurance for specific exposures (for instance, an additional treaty for winter storm coverage was put in place for the 2024-2025 winter). All of this helps cap Kingstone’s downside in worst-case scenarios.

Aggressive Expense Cutting

Cost-cutting delivered the fastest impact. Kingstone slashed its expense ratio from 41% in 2021 to about 31% by late 2023 — a huge swing. Management attacked costs on multiple fronts: layoffs, renegotiated vendor contracts, lower agent commissions, and tech-driven streamlining.

By Q3 2024, expenses had dropped below the industry average (~33%). That matters. Expense cuts are durable, unlike the loss ratio, which can swing wildly with the weather. Golden has made it clear: keeping a lid on costs remains a top priority.

The Numbers Behind Kingstone’s Historic Turnaround

These efforts collectively began to show up in the financial results by 2023 and really bloomed in 2024. The clearest evidence is in that all-important combined ratio. In 2021–2022, Kingstone’s combined ratios were abysmal (well over 100%). By contrast, 2024’s full-year combined ratio came in around 80.0% — an astonishing turnaround and a level of underwriting profitability that rivals the best in the industry. Kingstone’s combined ratio in the most recent quarter of 2024 was about 78%, which is extremely strong for a P&C insurer. This means KINS is now earning 20+ cents of underwriting profit on the dollar, before even accounting for investment income — a night-and-day difference from just two years ago.

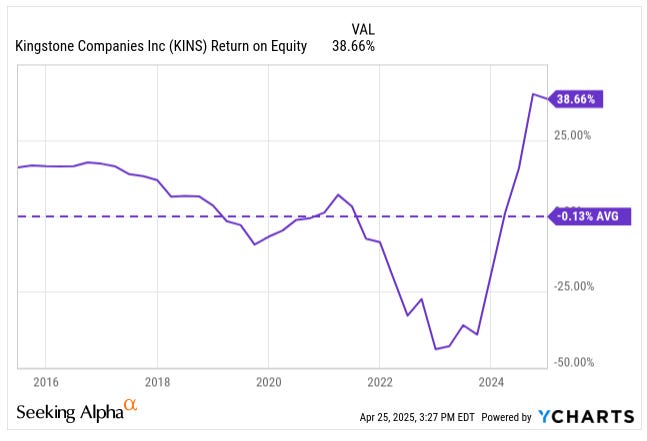

Let’s put some hard numbers to Kingstone’s comeback. In 2024, direct premiums written (the total policy premiums before reinsurance) grew ~21% to $242 million, reflecting both new business and rate increases. Net premiums earned (after ceding premiums to reinsurers) rose about 12% to $128.5 million. The loss ratio for the year improved dramatically to 48.7% from 72.4% in 2023, meaning claims were less than half of premiums in 2024, thanks to benign weather and better underwriting. Even excluding the effect of catastrophes, the loss ratio dropped over 18 points y/y, confirming that it wasn’t just good luck with the weather – core loss performance improved. The expense ratio also ticked down to 31.3% from 32.9%. Add it up, and the net combined ratio was 80.0% in 2024 versus 105.3% in 2023. This huge swing turned a net loss in 2023 into a solid profit in 2024. KINS earned $18.4 million in net income for 2024 (about $1.60 per share), compared to a loss of $6.2 million in the prior year. That’s the highest annual profit in the company’s recent history and the best results since Kingstone became a stock company in 2009. ROE for 2024 was over 36% — an almost eye-popping number, though off a small equity base that had been depressed by prior losses.

It’s worth highlighting that a chunk of this growth came from opportunistic market share gains (more on that in the next section), but also that the profits were aided by a mild catastrophe year in NY. KINS had virtually no hurricane or major catastrophy losses in 2024, which contributed about 5 points of improvement in the loss ratio vs. the prior year. The company can’t control the weather, so we shouldn’t expect every year to be as pristine, but they can control how they prepare for bad weather via reinsurance. On that front, Kingstone’s strategy of laying off risk worked as intended: even the handful of windstorms that did hit in 2023 were absorbed without much pain, and by 2024, the company had additional protections in place.

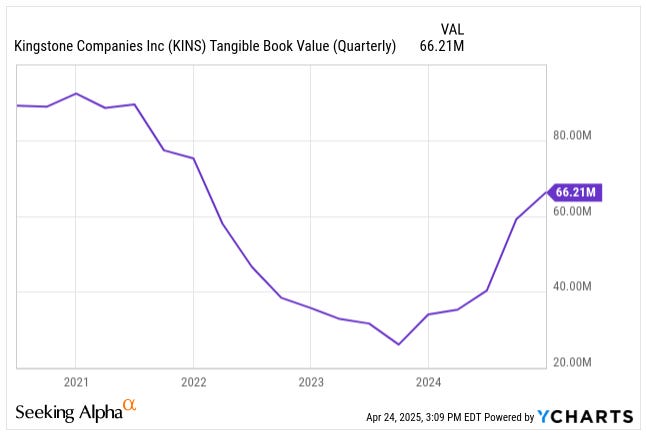

KINS also benefited from higher interest rates through its investment portfolio. In 2024, net investment income was $6.8 million, up ~14% from 2023. The company shifted its investments into shorter-term corporate bonds yielding around 4.2%, boosting income. While $6-7 million may not sound huge, for Kingstone it’s meaningful (roughly one-third of underwriting profit). Every extra dollar of interest earned goes straight to the bottom line and helps them post even better net results. The flip side is that rising rates dented the market value of the bond portfolio, which is why the book value per share (including unrealized losses) is only $4.73. Excluding those unrealized losses (which could reverse if bonds are held to maturity or if rates fall), book value would be $5.59 per share. Either way, Kingstone’s tangible book equity (~$4.82 per share) is still small, but it’s growing rapidly now that the company is profitable again.

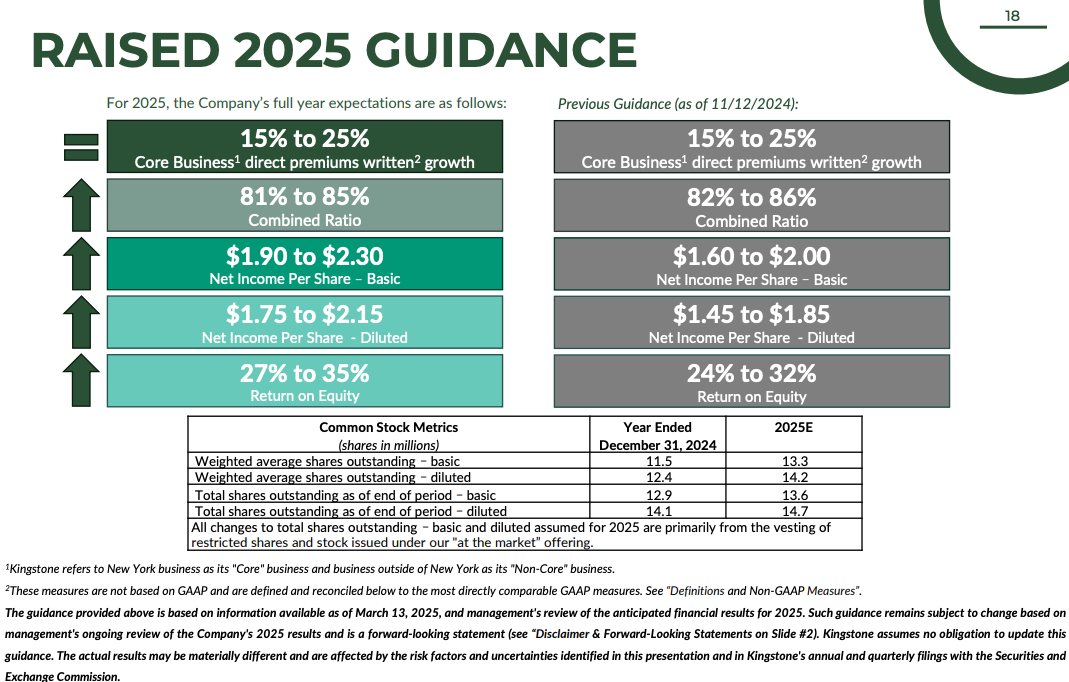

Perhaps the most encouraging aspect of Kingstone’s current state is that management believes these improvements are sustainable. In her year-end letter to shareholders, CEO Golden expressed optimism that the company can maintain its core premium growth and strong combined ratio into 2025. After three consecutive profitable quarters and a banner year, Kingstone is projecting continued growth. Kingstone provided guidance for 2025, calling for earnings in the range of $1.90 to $2.30 per share.

Hitting the low end of that guidance would be 18% higher or 30 cents better than 2024’s performance, while the high end implies a 44% improvement in EPS. Management has indicated that direct premiums could grow on the order of 30% again in 2025 if conditions remain favorable. The early signs are positive – the company ended 2024 with a lot of momentum, as we’ll discuss next.

Competitive Moat Deep Dive: Seizing NY Market Dislocation

Insurance is a notoriously competitive industry, especially in populous markets like New York. Dozens of insurers – from large national giants to small regional players – vie for customers. This competition can put pressure on pricing and make it hard for a tiny company like KINS to gain share. However, an unusual window of opportunity opened in mid-2024: two sizable competitors abruptly exited the New York homeowners insurance market.

In late July 2024, these insurers received regulatory approval to non-renew or cancel all their NY home policies by the end of the year. One of these was AmGUARD, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway’s Guard Insurance, which pulled out of NY’s homeowners business. The other carrier wasn’t named explicitly in disclosures, but the sudden withdrawal of two players created a vacuum in the market.

KINS was in a prime position to benefit. With its renewed focus on New York and long-standing relationships with local insurance brokers, Kingstone moved quickly to scoop up business from the exiting rivals. The company targeted the policies that fit its profitability criteria (they didn’t just indiscriminately take all comers, but were selective to ensure the new business would meet margin targets). The results of this land-grab were significant. By the end of 2024, Kingstone had acquired over 6,000 policies representing $23 million in direct written premiums from those displaced customers. This influx was a big driver of the 44% growth in core (NY) premiums in the second half of 2024. In full-year terms, Kingstone grew its NY personal lines direct premiums by 31% y/y, largely thanks to this opportunity.

It’s not often that competitors simply hand you their business, so this was a bit of serendipity lining up with preparation. Kingstone’s management rightly calls it a “unique opportunity” and is “extremely optimistic” that they can retain and build on these new customer relationships into 2025 and beyond. They even hinted that additional share gains are possible if other insurers retrench or if KINS leverages its strengthened position. The competitive shake-up essentially elevated Kingstone from a minor niche player to a somewhat larger niche player in the NY market overnight.

To put Kingstone’s scale in context: even after adding those 6,000+ policies, the company still has a modest slice of the overall New York market. Larger insurers like State Farm, Allstate, Travelers, Chubb, and the regional mutuals (e.g. New York Central Mutual) collectively insure a huge number of NY homes. Many of those bigger companies, however, are cautious about coastal exposures – for instance, Allstate stopped writing new homeowners policies in certain coastal NY areas years ago after hurricane scares. This means specialists like Kingstone can step in to cover homes that big nationals avoid. Kingstone’s advantage is being laser-focused on this region: it knows the local underwriting nuances (which neighbourhoods are flood-prone, which building codes mitigate wind damage, etc.), and it can provide tailored service through agents who are embedded in the community. Moreover, Kingstone’s smaller size and single-state focus mean that when the market environment shifts (like competitors leaving or regulators allowing rate hikes), the company can react nimbly without the bureaucratic inertia of a giant insurer.

That said, competition is never far away. There are other regional carriers in the Northeast that compete in similar segments – for example, Narragansett Bay Insurance and Plymouth Rock (both private companies) also write coastal home insurance in the region, and NYCM (New York Central Mutual) is a long-established upstate NY insurer that also covers downstate. Large multi-state insurers such as The Hartford or Progressive might not focus on home insurance in NY as a core line, but they could decide to grow in this area, especially if they smell profits. So Kingstone will have to continue differentiating itself via underwriting expertise and agent relationships.

The exits of 2024 may have been driven by those competitors finding the NY market unprofitable, which raises an eyebrow:

Why could Kingstone make money where others could not?

The likely answer is in Kingstone’s selective approach (they didn’t take the bad with the good) and perhaps a bit of timing (those insurers might have been caught with inadequate pricing or reinsurance when loss costs spiked). Now that KINS has cherry-picked many of the desirable policies, any future entrant would have to compete to take those away, potentially on price. Kingstone’s recent strong results could, ironically, attract more competition if others see that profits can be made. So the company will need to continuously prove its underwriting edge to defend its turf.

At the moment, though, the competitive landscape looks favourable for Kingstone. Fewer players in the NY home insurance space means rational pricing can prevail. Kingstone’s management has indicated they remain confident in their positioning and don’t intend to chase growth at the expense of profitability. The focus is on “profitable market share” — a refreshing discipline that bodes well if they stick to it. In summary, Kingstone turned a potential industry shake-up into a growth catalyst and is now a bigger fish (albeit in a limited pond). The key will be holding onto those new customers and becoming their long-term insurer of choice.

Macro & Regulatory Factors for NY Insurance Stocks

Insuring homes in downstate New York comes with its own set of challenges and quirks. It’s not Florida or California, but it’s not without risks.

Catastrophe Exposure

New York City and Long Island are not frequent targets of hurricanes, but when storms do hit, the damage can be enormous due to the density and value of properties. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 was a stark reminder of this, causing widespread flood and wind damage in the region. (Notably, flood insurance is mostly handled by the federal NFIP, but wind damage falls to private insurers.) Kingstone’s portfolio is exposed to the tail risk of a major hurricane or coastal storm. Winter nor’easters can also cause significant property damage (roof collapses, ice, etc.), and severe thunderstorms can bring hail or tornadoes even in the Northeast.

Kingstone has dodged major storms so far. But don’t mistake a few quiet years for lasting safety. The Northeast, and New York specifically, is not immune to major hurricanes — it's simply been lucky for a while. According to historical data from the National Hurricane Center, a hurricane directly affecting the New York City area occurs approximately every 19 years, and a Category 3 or higher “major” hurricane strikes the region about once every 70–75 years. The last to make serious landfall was Hurricane Gloria in 1985 — nearly 40 years ago — and the devastating impact of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, while technically a post-tropical cyclone, highlighted just how vulnerable the region remains.

More concerning is what climate models now suggest: that frequency and severity are both likely to increase. A recent peer-reviewed study using the Columbia Hazard model (CHAZ) found that climate change could meaningfully increase hurricane wind risks in New York, with flooding events like Sandy potentially becoming once-every-30-years occurrences by the end of this century.

For Kingstone, that means the true test may still lie ahead. The company’s reinsurance structure does cap its exposure to extreme events, but even with that protection, a direct hit from a major hurricane, especially in Long Island or the New York City boroughs where Kingstone has heavy exposure, could produce significant losses. This is the nature of insuring coastal property: you can underwrite perfectly for years, and one event can still wreck a balance sheet. That doesn’t make KINS uninvestable — but it does mean the business is inherently cyclical and weather-sensitive.

Regulatory Environment

New York’s regulators are known to be tough and consumer-oriented. The Department of Financial Services oversees insurance rates and must approve significant rate changes. This can sometimes lag cost trends – for example, if inflation in construction costs jumps 10%, insurers might want to raise premiums equivalently, but regulators could slow-walk approval. KINS has navigated this by steadily implementing necessary rate increases (as seen with the selective hikes for its products in 2024). The flipside of strict regulation is that DFS also won’t let insurers arbitrarily drop customers; even those two competitors needed permission to exit the market. New York wants a stable insurance market, so if KINS remains a reliable provider, the regulators likely view it as a positive force.

However, regulation can limit how fast KINS expands or how quickly it can adjust prices, which could squeeze margins if inflation or claim frequency spikes unexpectedly. Furthermore, there are rules on capital and dividends – in Kingstone’s case, for a while, the insurance subsidiary was not allowed to distribute dividends to the holding company due to past losses. That meant the parent company had to raise funds via equity to service debt and expenses. Thankfully, with profits returning, this restriction has eased, but it’s a reminder that in NY, you can’t upstream capital freely without meeting regulatory tests.

High Cost, High Value Area

Downstate New York has very high property values (think expensive homes in NYC suburbs), which means average policy sizes (premium per policy) are relatively high. This is good in that Kingstone collects healthy premiums, but it also means a single claim – say a house fire or a liability lawsuit – can be quite large. It requires careful underwriting to ensure each policy is appropriately priced for its risk.

Additionally, the cost to repair or rebuild homes in NY is high due to labour and material costs, so claims can be more expensive than in other parts of the country. KINS has addressed this by updating replacement cost assumptions annually and tightening underwriting for older or riskier homes. They’ve noted that the newer “Select” policies have lower loss frequency, which could be partly due to insuring newer or better-maintained properties that are less likely to have big losses.

Demographics and Market Nuances

The NY market has a dense population, and many insureds get their policies through independent agents. Kingstone’s reliance on agents is a strength in NY, where personal relationships and service matter. It’s not a direct-to-consumer or online-driven market as much as some others; people often buy home insurance through the same local broker who handles their auto or business insurance. Kingstone’s long history and local presence likely help it in maintaining trust with these agents. Also, New York’s market hasn’t seen the proliferation of insurance startups or insurtech disruptors that some other states have. Customers tend to stick with known quantities. This conservative market culture can benefit an incumbent like Kingstone, provided it maintains a good reputation and financial stability (no one wants to buy insurance from a company they fear might go belly-up in the next storm).

Valuation: Is There Upside Left?

With Kingstone’s stock now around $18, a lot of the turnaround’s success is already reflected in the price. The stock has rallied massively from its lows, and it no longer looks like the deep bargain it once was.

By the Earnings Numbers

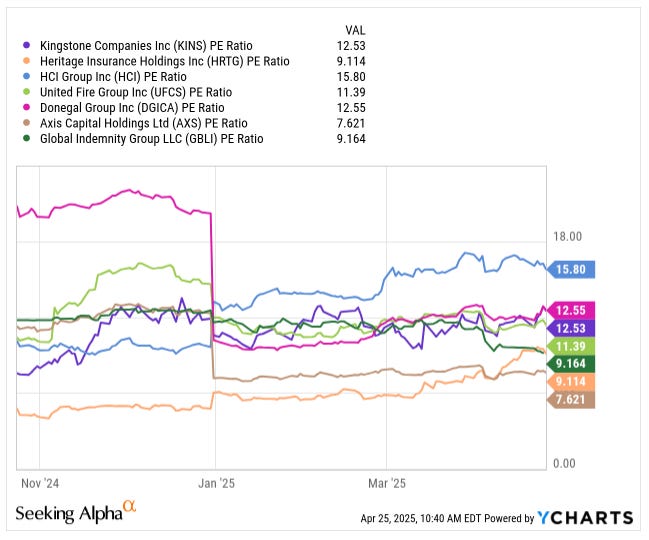

At the current price, Kingstone trades roughly 12 times its trailing earnings. On a forward basis, the forward P/E is 7.8 to 9.5x based on the $1.90-$2.30 EPS guidance. That’s not a demanding multiple – it’s in line with or slightly below the market average.

However, insurance stocks often trade at low P/Es because their earnings can be volatile (one bad quarter can knock down a full year’s profit). Among small regional insurers, a 10x P/E is about middle-of-the-pack; peers trade anywhere from ~7x to ~16x earnings depending on their circumstances.

So Kingstone isn’t obviously cheap or obviously expensive on a P/E basis — it’s reasonable. It’s worth noting that Kingstone’s historical P/E (when it was profitable years ago) was higher, often in the teens or even 20s.

But comparing to that is tricky because past earnings were erratic. For a company now growing earnings rapidly, one could argue a higher multiple is warranted; on the other hand, given Kingstone’s small size and risk exposure, many investors will demand a discount.

While a re-rating is possible, I am betting on the earnings to grow faster than expected. KINS has 2.1% of the NY homeowners market, and I suspect that share could continue to expand as the dust settles from recent competitor exits. Of the ~$260 million in displaced premiums, Kingstone secured about $70 million through its renewal rights transaction, and while it’s likely that a portion of the remaining ~$190 million has already been absorbed by other insurers, there is still a meaningful pool of business up for grabs. With strong relationships through independent agents and a sharpened underwriting approach, Kingstone is well-positioned to pick off profitable risks selectively. Even modest additional gains in market share — layered on top of disciplined expense management — could allow earnings to grow faster than the market currently appreciates. In short, I’m not relying on a multiple expansion to drive returns; I’m betting the "E" in P/E will keep compounding.

I wouldn’t be surprised if 2025 EPS comes in closer to $2.40, which would imply a $24 stock at a 10x multiple. But let’s anchor on the higher end of management’s guidance, which points to a target price around $23, representing roughly a 27% upside from current levels.

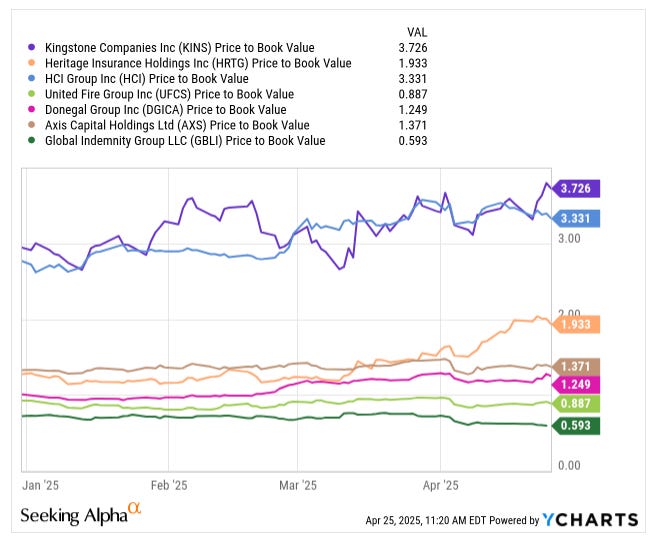

By the Book

On a P/B basis, KINS does look pricey: at ~$18 share price vs. $5.16 book value per share, the P/B is about 3.5x. Many insurance companies trade at around 1x book or even below if they have mediocre prospects.

Kingstone’s high P/B reflects investors’ expectations of strong ROE. I am not going to derive it, but the following formula provides the relationship of P/E to ROE, where g is the sustainable earnings growth rate and k is the cost of equity.

P/E = (1 - g/ROE)/(k-g)

In simple terms, the higher the ROE, the higher the P/E multiple an insurer can command. With KINS now trading at nearly 3.5x book value, the market is assuming the company can sustain ROEs north of 25%.

ROE was off the charts in 2024 (~36%), but that’s likely to normalize lower over time. In insurance, it's dangerous to assume that near-perfect conditions will persist indefinitely. A single major event — a hurricane, a severe windstorm, or an unexpected spike in claims inflation — can wipe out an entire year’s worth of underwriting profits. While Kingstone's management has clearly tightened discipline and improved the risk profile, some degree of earnings volatility is simply inherent to the business model.

If we assume KINS can sustain, say, a 15–20% normalized ROE, paying ~3× book value today is borderline reasonable. The stock is no longer a "value steal" as it was at much lower levels, but it’s also not necessarily overvalued if those high returns prove durable. High-growth, high-ROE insurers do tend to trade at premiums to book; the challenge is that very few small insurers sustain exceptional ROEs for long. Competition, pricing cycles and weather risks usually bring returns back toward more average levels. In short, today's valuation makes sense if the new Kingstone proves resilient, but leaves a thinner margin for error if profitability reverts toward industry norms.

Risks and Challenges: Catastrophe, Regulation & Dilution

No investment is without risks, and insurance companies have their fair share. Here are the key risks an investor in Kingstone should keep in mind.

Catastrophe and Weather Risk

By virtue of its business, KINS is exposed to hurricanes, windstorms, winter storms and other natural disasters in the Northeast. A single large hurricane hitting Long Island could result in claims far beyond normal levels, potentially flipping the company to a loss in that year and damaging its capital. KINS does buy extensive reinsurance (up to $275 million of catastrophe coverage), but its retention (the deductible it pays) is a few million dollars per event, and multiple events could also strain it. As climate change potentially increases the frequency of severe weather, this is an ever-present risk. The company could face multiple smaller catastrophes that aggregate (e.g., a bad winter with many ice damage claims) or one mega-catastrophe — either would hurt. Investors must be prepared for volatility; an 80% combined ratio year could be followed by a 120% combined ratio year if Mother Nature is cruel.

Regulatory and Political Risk

Insurance is heavily regulated by state authorities. New York’s regulators could impose restrictions that affect Kingstone’s profitability. For instance, rate hike approvals might not keep up with inflation, or the state could temporarily ban policy non-renewals during emergencies (forcing insurers to cover higher risks than they want to). In extreme cases, there’s the risk of adverse legislative changes – e.g., mandates to cover certain perils or limits on underwriting criteria – which could disrupt Kingstone’s business model. Also, Kingstone’s ability to upstream cash (dividends from KICO to the holding company) is subject to regulatory approval. If, for any reason, KICO couldn’t dividend money, the parent company might have trouble servicing its obligations without diluting shareholders (a situation they faced in 2020-2022).

Competitive Pressure and Market Pricing

The favourable competitive situation could change. If those insurers that left decide to come back (perhaps after retooling their pricing) or if new entrants (including insurtech companies or other regionals) target New York, KINS might find it harder to grow or even maintain its book. A larger competitor could also undercut pricing to gain market share, forcing KINS to choose between losing customers and accepting lower margins.

Being a small player, KINS doesn’t have much market power – it can’t set industry prices, it mostly has to react to the environment. The current discipline in the market could erode if, say, the industry goes into a soft pricing cycle. Kingstone’s recent growth partly came from a one-time event; going forward, organic growth might be tougher, especially if they stick to tight underwriting (which is good for profit but means turning away business that doesn’t meet criteria).

Execution and Growth Management

Growing ~20-30% in premiums in a single year, as Kingstone just did, is a nice “high-class” problem to have – but it can strain an organization. Rapid growth can lead to operational hiccups: servicing all the new policies, handling claims efficiently, and maintaining customer/agent satisfaction are all challenges. There’s also a risk that in pursuing growth, underwriting standards could slip inadvertently (writing a lot of new business quickly sometimes leads to mistakes or accepting some bad risks). So far, Kingstone appears to be managing this well, but it requires vigilance to ensure that growth remains profitable growth.

Additionally, the company’s technology and systems need to scale with growth; any weakness in their claims systems or pricing models could be exposed as volume rises. In short, KINS must prove it can handle being a bigger company than it was a year ago.

Reinsurance Availability and Cost

Kingstone’s heavy use of reinsurance is a double-edged sword. While it protects the company from big losses, it also means Kingstone is reliant on reinsurers. If global reinsurance costs continue to rise (as they have in recent years due to worldwide catastrophe losses), KINS might face significantly higher reinsurance premiums at renewal. That would either compress margins or force KINS to pass costs onto customers (which could make its pricing less competitive). In a worst-case scenario, if reinsurance markets tighten dramatically, Kingstone might not be able to buy as much coverage as it wants at an economical price, leaving it more exposed. So far, they’ve managed to secure what they need, but it’s a point to watch each year around the reinsurance renewal season.

Financial Strength and Dilution Risk

Kingstone’s balance sheet, while much improved, is still relatively small. The company’s statutory surplus (the capital cushion for the insurance subsidiary) is a limiting factor on how much premium it can write. If KINS wants to keep growing rapidly, it either needs to retain earnings to boost surplus or find other ways to add capital. In the past, they issued stock when in a bind. While current management is loath to dilute shareholders, they did project an increase in share count from 12.3 million to ~14.2 million by 2025 through at-the-market issuances. If a big loss hit, it’s possible they’d need to raise capital again to shore up reserves. The risk of future dilution isn’t high at the moment, but it’s not zero. Similarly, if Kingstone wanted to opportunistically grow via acquiring another book of business, it might need funding. Any such moves could dilute the value for existing shareholders if not done carefully.

Micro-Cap Stock Risks

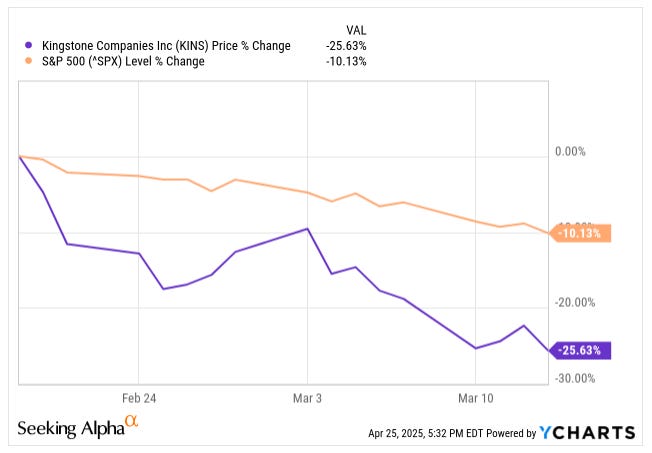

Finally, as a micro-cap stock with a market cap of around $250 million, Kingstone’s shares are inherently more volatile and less liquid than those of larger companies. Small caps often move more sharply during market turbulence, and KINS is no exception. When sentiment turns risk-off, smaller names tend to get hit harder, not necessarily because of fundamentals, but because liquidity dries up and risk appetite shrinks. For instance, by mid-March, while the S&P 500 had pulled back about 10% from its highs, KINS shares had fallen roughly 25%, illustrating just how amplified the swings can be.

Conclusion: Hold the King’s Stone or Cash in the Gains?

Revisiting KINS at $18+, after having entered around $10, feels like arriving at a crossroads. The turnaround thesis we believed in has largely played out: a struggling regional insurer got its act together, grew impressively, and returned to robust profitability. The stock responded in kind, delivering substantial gains. Now the easy part — identifying a deeply undervalued company on the brink of improvement — is behind us. The hard part is deciding what comes next.

On one hand, Kingstone’s fundamental picture is brighter than it has ever been. The company is running an underwriting profit, gaining share in its niche, and managing costs astutely. It has a clear strategy and a management team that executed well on its initial goals. One must also trust the relatively new management’s execution — we don’t yet have a long multi-year track record under Meryl Golden's leadership, only very strong initial results. But based on what we’ve seen so far, the operational turnaround has been real and substantial. If KINS can sustain even a good portion of its 2024 performance in the coming years, the current valuation will end up looking quite justified, and there may be more upside. Continued growth in premiums (even at a more modest pace) combined with combined ratios in the 80% could generate high-teens millions in earnings annually.

On the other hand, a lot of good news is already baked into the stock price after the rally. The valuation is no longer dirt-cheap, and any slip-up could result in a pullback. Owning an insurer above 3x book value requires confidence that exceptional performance will persist. Any regression toward the mean — say, a combined ratio creeping back into the 90s or premium growth stalling out — could cause the market to reset the multiple lower. The looming risks (catastrophes, competition, etc.) are not trivial, and KINS hasn’t yet been tested under Golden’s leadership by a severe crisis or loss event.

I’d lean toward holding a core position. Kingstone’s turnaround has real legs, and the company’s niche focus could allow it to compound value over several years. The fundamentals do support the current stock level and potentially a bit more, assuming execution remains strong. It’s not outrageously valued given its growth.

That said, while I intend to keep KINS in the portfolio, I recognize that the easy money has already been made. I’m staying invested not just to capture the remaining 20–30% potential upside, but because I believe the new management team has executed exceptionally well so far, and could still surprise us with additional growth or strategic wins. However, the risk-reward profile is no longer as attractive as before. If I need to raise cash for new opportunities or build a cushion, KINS may now become a candidate for partial trimming or rebalancing.

In conclusion, Kingstone’s turnaround has been golden indeed, and the company’s fundamentals have caught up to its stock price. While the era of 400% returns in a year is likely behind us, this King of the New York insurance niche still has room to reign if it stays on course. The key will be watching those core metrics — combined ratio, growth, and reserves — like a hawk. If they remain favourable, KINS could keep rewarding patient investors; if cracks appear, don’t hesitate to act. As of now, the scales tip toward continuing to hold the bulk of the position, acknowledging the company’s strong fundamental footing, but with a sharper eye on the horizon and the readiness to adjust if conditions change. After all, in the world of insurance, one must always prepare for the next storm even on a sunny day.